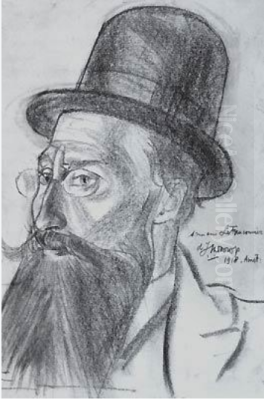

Henri Le Fauconnier stands as a significant, though sometimes overlooked, figure in the dynamic landscape of early 20th-century European art. Active during a period of radical artistic transformation, he played a crucial role in the development and dissemination of Cubism, while also forging connections with Expressionism and influencing the course of modern art, particularly in France and the Netherlands. Born in Hesdin, Pas-de-Calais, France, on July 5, 1881, and passing away in Paris on December 25, 1946, Le Fauconnier's life spanned a tumultuous era, and his art reflects the intellectual and aesthetic ferment of his time. His journey from law student to avant-garde painter reveals a commitment to artistic exploration that placed him at the heart of modernist debates and innovations.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Initially destined for a career in law, Henri Victor Gabriel Le Fauconnier moved to Paris in 1901 to pursue legal studies. However, the vibrant artistic atmosphere of the French capital soon captivated him, leading him to abandon law for painting. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school known for its relatively liberal approach compared to the official École des Beaux-Arts. There, he studied under the academic painter Jean-Paul Laurens, absorbing traditional techniques while simultaneously being exposed to the burgeoning modern art movements swirling through Paris.

Le Fauconnier's early artistic inclinations were shaped by the prevailing Post-Impressionist and Fauvist currents. He deeply admired the work of Paul Cézanne, whose emphasis on underlying geometric structure and the construction of form through color profoundly influenced many artists of Le Fauconnier's generation, including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. The Fauvist movement, led by Henri Matisse and André Derain, with its bold, non-naturalistic colors and expressive brushwork, also left its mark on his initial output. He began exhibiting his work, making his debut at the Salon des Indépendants in 1904 and 1905. This annual, unjuried exhibition was a crucial venue for avant-garde artists seeking to showcase work that challenged academic conventions. His paintings from this period often displayed the bright palettes and simplified forms characteristic of Fauvism.

The Forefront of Cubism

By 1909, Le Fauconnier's style began to shift decisively towards Cubism. He became associated with a group of artists who gathered in the Parisian districts of Montparnasse and Puteaux, distinct from the Montmartre circle initially dominated by Picasso and Braque. This group, often referred to as the "Salon Cubists" or "Puteaux Group," included key figures like Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay, and Juan Gris. Unlike the more private, gallery-focused development of Picasso and Braque's Analytical Cubism, these artists actively promoted their interpretation of Cubism through large-scale public exhibitions, particularly the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d'Automne.

Le Fauconnier quickly emerged as a leading figure within this group. His work from 1910-1912 is considered central to the development of Salon Cubism. He adapted Cézanne's principles of geometric simplification and multiple viewpoints, combining them with a darker palette than his Fauvist phase and a greater emphasis on complex, interlocking planes and dynamic compositions. His paintings often retained recognizable subject matter – figures, landscapes, still lifes – but subjected them to rigorous formal analysis and reconstruction. He employed strong outlines and faceted forms, creating a sense of volume and structure that was both modern and monumental.

His participation in the Salon des Indépendants of 1910 and, most notably, 1911, cemented his reputation. In the 1911 Salon, the Cubists deliberately grouped their works together in Salle 41, creating a succès de scandale. Le Fauconnier exhibited his large, ambitious painting L'Abondance (Abundance, 1910-11). This allegorical work, depicting a female nude with a cornucopia alongside other figures in a landscape, synthesized Cubist fragmentation with a certain classical grandeur. It became one of the most discussed and reproduced works of the exhibition, seen as a major statement of the new aesthetic. Critics, both hostile and supportive, recognized Le Fauconnier, alongside Metzinger and Gleizes, as a principal exponent of the burgeoning movement.

Montparnasse, Contemporaries, and Controversy

Le Fauconnier was an active participant in the intellectual and artistic life of Montparnasse. He associated not only with the core Salon Cubists but also interacted with the broader avant-garde community. While he shared the fundamental goals of Cubism with Picasso and Braque – challenging traditional perspective and representation – his approach differed. Le Fauconnier's Cubism often retained a more descriptive quality and a connection to traditional genres, sometimes incorporating symbolic or allegorical content, as seen in Abondance. His work, and that of the Salon Cubists generally, tended towards larger formats suitable for public exhibition, contrasting with the more intimate scale often favored by Picasso and Braque during their Analytical Cubist phase.

The 1911 Salon des Indépendants brought both recognition and controversy. The radical nature of the works shown in Salle 41 provoked outrage from conservative critics and the public. Terms like "ignorant geometers" and accusations of reducing everything to "cubes" were common, echoing the earlier derision faced by the Fauves. While this notoriety helped publicize Cubism, it also highlighted internal tensions. Le Fauconnier's style, sometimes perceived as retaining stronger links to tradition or even incorporating elements of Expressionism through its dynamism and occasional emotional intensity, set him slightly apart.

Further disagreements arose within the Cubist circle. By 1912, Le Fauconnier began to distance himself from some collective activities. While he was initially involved with the Section d'Or (Golden Section) group, which organized a major exhibition later that year, his participation lessened. This might have stemmed from stylistic divergences or personal dynamics within the rapidly evolving avant-garde scene. His relationship with contemporaries like Picasso and Braque appears to have been one of mutual awareness and interaction within the same artistic milieu, rather than close collaboration or direct partnership. He pursued his own distinct path within the broader Cubist framework.

Theoretical Ideas and Artistic Vision

Like several of his contemporaries, notably Gleizes and Metzinger who co-authored the first major treatise Du "Cubisme" (On Cubism) in 1912, Le Fauconnier was interested in the theoretical underpinnings of the new art. He contributed an important theoretical text to the catalogue of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM) exhibition in Munich in 1910. This connection highlights his early international reach and his engagement with artists outside Paris, including Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and Alexej von Jawlensky, who were then laying the groundwork for German Expressionism and abstract art.

Le Fauconnier's writings, particularly later ones, sometimes attempted to define artistic principles through complex, almost mathematical systems relating form and color. These theoretical explorations, however, were often considered somewhat obscure or overly systematic by critics and fellow artists, and they did not achieve the widespread influence of Du "Cubisme". Nevertheless, they reveal his intellectual engagement with the fundamental questions of representation, form, and the very nature of painting that Cubism raised.

His artistic vision consistently sought a balance between radical formal innovation and a sense of structure and legibility. He aimed to dissect reality into its geometric components but reassemble them into powerful, coherent compositions. His work often possesses a dynamic energy, a sense of movement and force, that distinguishes it from the more static, analytical approach of early Picasso and Braque. This dynamism, combined with his sometimes somber palette and robust forms, created a bridge between the structural concerns of Cubism and the emotional intensity associated with Expressionism. Works like Les Montagnards attaqués par des ours (Mountaineers Attacked by Bears, c. 1912) exemplify this dramatic and powerful style.

International Reach and the Dutch Influence

Le Fauconnier's influence extended beyond France even before World War I. His involvement with the NKVM in Munich connected him to the nascent German Expressionist movement. Kandinsky, in particular, admired his work and invited him to participate in their exhibitions. This placed Le Fauconnier at a crucial intersection of French and Germanic avant-garde developments. His work was exhibited in Moscow as well, reflecting the keen interest Russian artists like Kazimir Malevich, Liubov Popova, and Alexander Archipenko took in Parisian innovations.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a significant turning point. Finding himself in the Netherlands when the war began, Le Fauconnier remained there for the duration of the conflict, until 1920. This extended stay proved highly influential for Dutch modern art. He became a central figure for a group of Dutch artists, including Piet van Wijngaerdt and Jacoba van Heemskerck, who were seeking to move beyond their own traditions. Le Fauconnier's powerful, structured style, blending Cubist geometry with expressive force, provided a potent model.

During his time in the Netherlands, Le Fauconnier's style continued to evolve, absorbing some aspects of the local environment while profoundly shaping it. He became associated with the Bergen School (Bergense School), an art movement centered around the village of Bergen near Amsterdam. This school, largely inspired by Le Fauconnier and the French avant-garde, favored a form of Expressionism characterized by dark, earthy tones, figurative subjects often depicting rural life, and bold, angular forms influenced by Cubism. Le Fauconnier painted numerous Dutch landscapes and portraits during this period, adapting his style to new subjects and contributing significantly to the development of Dutch Expressionism. He also published theoretical articles in Dutch journals like Het Signaal, advocating for an art that was both formally pure and socially engaged.

Later Career, Teaching, and Legacy

After returning to Paris in 1920, Le Fauconnier found the art world transformed. While Cubism had paved the way for numerous subsequent movements, its heroic phase was largely over. Surrealism was emerging as a dominant force, and many artists were exploring different directions, including a "return to order" inspired by classicism. Le Fauconnier continued to paint and exhibit, but his work gradually moved away from the radical edge of the avant-garde. His style became somewhat softer, though still retaining structural solidity.

Despite his significant contributions in the pre-war years, Le Fauconnier's profile began to diminish in the interwar period. He did not achieve the sustained international fame of Picasso, Braque, or Léger. Part of this may be due to his departure from Paris during the crucial war years and his subsequent evolution away from mainstream Parisian trends. He focused more on consolidating his style rather than pursuing constant, radical innovation.

However, his legacy endured, not least through his teaching. For a time, Le Fauconnier taught at the Académie de La Palette in Paris, an important progressive art school where he worked alongside Jean Metzinger. Through his teaching, he influenced a number of younger artists. While specific student lists can be debated, artists associated with La Palette during this period included Liubov Popova and Nadezhda Udaltsova, key figures of the Russian avant-garde, as well as the sculptor Alexander Archipenko, whose work clearly shows Cubist influence. His ideas and methods disseminated through these channels.

Le Fauconnier died of a heart attack in his Paris studio in 1946. By this time, he had faded considerably from public view, almost becoming a forgotten figure of the pre-war avant-garde. However, subsequent art historical reassessment has increasingly recognized his vital role. His works are now held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Key Works Revisited

Several key works encapsulate Le Fauconnier's artistic journey and contribution:

L'Abondance (Abundance, 1910-11): This seminal work of Salon Cubism demonstrates his ability to synthesize Cubist fragmentation with allegorical subject matter and a sense of monumental composition. Its exhibition at the 1911 Salon des Indépendants was a landmark moment for the public reception of Cubism.

Les Montagnards attaqués par des ours (Mountaineers Attacked by Bears, c. 1912): Exhibited at the Salon d'Automne in 1912, this painting showcases the dynamic, expressive, and somewhat dramatic side of Le Fauconnier's Cubism. The angular forms, dark palette, and violent subject matter push Cubist principles towards an almost Expressionistic intensity.

Le Chasseur (The Huntsman, 1912): Another significant work from his peak Cubist period, demonstrating his mastery of complex, faceted forms applied to the human figure within a landscape, creating a powerful synthesis of subject and environment.

Village de Ploumanach (Village in Brittany, c. 1910-1914): Representative of his landscape work, these paintings apply Cubist principles of geometric simplification and structured composition to the rugged coastal scenery of Brittany, where he often spent time before the war.

Dutch Period Works (1914-1920): His portraits and landscapes from the Netherlands reflect the influence of the Bergen School, often employing darker colors, strong contrasts, and robust forms, while retaining the underlying structure derived from his Cubist experience.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Movements

Henri Le Fauconnier occupies a crucial position in the narrative of modern art. He was not merely a follower of Picasso and Braque but a key innovator within Cubism, particularly instrumental in shaping its public face through the Salon exhibitions. His unique interpretation of Cubist principles, characterized by dynamic composition, structural solidity, and a willingness to engage with complex subject matter, set him apart. His work provided a vital link between the analytical dissections of early Cubism and the more synthetic, colorful, and sometimes expressive developments that followed.

Furthermore, his role as a conduit between Parisian Cubism and international movements, especially German Expressionism via the NKVM and Dutch modernism through his extended stay and involvement with the Bergen School, underscores his importance. He was a transmitter of ideas and a catalyst for artistic change in multiple contexts. While his later career saw him move away from the vanguard, his contributions during the formative years of modernism remain undeniable. Henri Le Fauconnier was a pivotal figure whose art bridged styles and borders, leaving an enduring mark on the trajectory of 20th-century painting. His work continues to be studied for its formal power, its historical significance, and its unique synthesis of structure and expression.