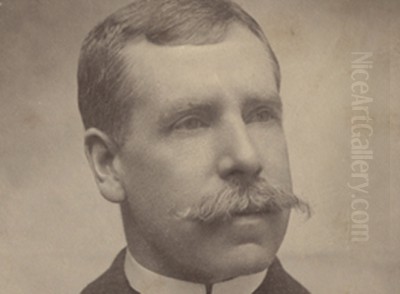

Aloysius Constantine O'Kelly stands as a fascinating, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century art. An Irish painter and illustrator born in Dublin in 1853, his life and work traversed geographical boundaries and artistic styles, reflecting a complex engagement with Irish identity, global travel, and the turbulent political currents of his time. His career saw him move from the academic studios of Paris to the rugged landscapes of Connemara, the battlefields of Sudan, the bustling souks of North Africa, and finally, the urban environment of New York City. O'Kelly's art is a compelling blend of meticulous academic technique, Realist observation, Orientalist fascination, and a subtle infusion of Impressionistic light and colour, all while often serving as a visual commentary on the social and political realities he witnessed. He died in 1941, leaving behind a body of work that continues to intrigue scholars and art lovers alike.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Dublin and Paris

Aloysius O'Kelly was born into a Dublin family deeply enmeshed in the fabric of Irish nationalism. His father, John Kelly, and mother, Bridget, raised their children in an environment where political discourse was commonplace. This was particularly evident in the career of Aloysius's elder brother, James Joseph O'Kelly, who became a prominent journalist, war correspondent, and Parnellite Member of Parliament, known for his staunch Irish republicanism and involvement with the Fenian movement. This familial connection to nationalist politics undoubtedly shaped Aloysius's worldview and would later surface thematically in his art, particularly his depictions of Irish rural life and the struggles associated with the Land War.

Seeking formal artistic training, the young O'Kelly travelled to Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world in the latter half of the 19th century. He enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of French academic art. There, he entered the atelier of Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most famous and influential painters of the era. Gérôme was renowned for his mastery of academic technique, his historical paintings, and, perhaps most significantly for O'Kelly's later development, his highly detailed and popular Orientalist scenes derived from his own travels in the Near East.

Studying under Gérôme provided O'Kelly with a rigorous foundation in drawing, composition, and the precise rendering of form and texture. This academic training would remain a visible element throughout his career, even as he experimented with other stylistic approaches. The exposure to Gérôme's Orientalist works also planted a seed of interest in depicting cultures and landscapes beyond Europe, a theme O'Kelly would later explore extensively through his own travels. Life in Paris also exposed him to the burgeoning Impressionist movement, led by artists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, though O'Kelly never fully embraced their revolutionary techniques, preferring a more grounded realism.

Brittany and the Emergence of Realism

Before fully immersing himself in Irish subjects or venturing further afield, O'Kelly spent significant time in Brittany during the late 1870s. This region of northwestern France, with its distinct culture, traditional dress, and rugged coastal scenery, had become a popular destination for artists seeking picturesque and 'unspoiled' subject matter, away from the rapid modernisation of Paris. Artists like Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard would later make Pont-Aven famous, but O'Kelly was part of an earlier wave drawn to the area's perceived authenticity.

His Breton paintings demonstrate a move towards Realism, focusing on the everyday lives of the local population – fishermen, market vendors, and peasants in traditional costume. Works from this period often show a careful observation of light and atmosphere, perhaps absorbing some ambient influence from the Impressionists, but retaining the solid drawing and compositional structure learned under Gérôme. He depicted market scenes, harbours, and domestic interiors with an eye for detail and character.

This period in Brittany was crucial for O'Kelly's development. It allowed him to hone his skills in depicting specific regional identities and landscapes outside the confines of the Paris studio. It also solidified his interest in portraying rural communities and their ways of life, themes that would resonate powerfully when he turned his attention back to his native Ireland, particularly the west. His experiences in Brittany provided a template for observing and recording distinct cultural practices and social conditions, skills that would prove invaluable both in Ireland and later in North Africa.

Return to Ireland: Art and the Land War

The late 1870s and early 1880s saw O'Kelly return to Ireland during a period of intense social and political upheaval – the Land War. This agrarian conflict pitted tenant farmers, often living in dire poverty and facing eviction, against landlords, many of whom were Anglo-Irish aristocrats. The Irish National Land League, advocating for fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure (the "Three Fs"), orchestrated widespread protests, rent strikes, and boycotts. Given his family background and nationalist sympathies, O'Kelly was naturally drawn to documenting this struggle.

His work from this period provides a poignant visual record of conditions in rural Ireland, particularly in the west, in areas like Connemara. He depicted the hardships faced by tenant farmers, scenes of eviction, and the quiet dignity of communities struggling for survival. Unlike some romanticised depictions of Irish peasant life, O'Kelly's work often carried a strong undercurrent of social commentary, aligning him with the Realist tradition of artists like Gustave Courbet or Jean-François Millet in France, who used their art to highlight the conditions of the working class and peasantry.

His paintings and illustrations from this time often focused on the textures of poverty – the rough-hewn interiors of cabins, the worn clothing of the inhabitants, the bleakness of the landscape – but also captured moments of communal solidarity and religious faith. This period cemented O'Kelly's reputation as an artist deeply engaged with the realities of Irish life and sympathetic to the nationalist cause. His ability to combine technical skill with empathetic observation made his Irish works particularly powerful.

Chronicler of Conflict: O'Kelly as Illustrator

Beyond his work as a painter, Aloysius O'Kelly established a significant career as a special artist or illustrator for prominent news publications, most notably the Illustrated London News. This role was akin to that of a modern photojournalist, requiring artists to travel to locations of interest – often conflict zones or areas undergoing significant events – and produce accurate sketches that could be quickly engraved and published to inform a wide readership. This demanded speed, accuracy, and a keen eye for narrative detail.

His assignments took him beyond Ireland. He covered the Mahdist War in Sudan in the mid-1880s, providing dramatic illustrations of battles and military life. This experience directly fed into his growing interest in Orientalist subjects, providing firsthand material that was arguably more immediate and less romanticised than the studio-based creations of some contemporaries. His illustrations captured the harsh realities of colonial warfare and the landscapes of North Africa.

His work for the Illustrated London News, particularly his depictions of the Irish Land War, gained international attention. Notably, Vincent van Gogh, then living in the Netherlands, saw and collected O'Kelly's illustrations of Irish peasant life and evictions. Van Gogh expressed admiration for the raw emotion and social realism conveyed in these images, seeing in them a shared interest in depicting the lives of the poor and labouring classes. This connection highlights the reach and impact of O'Kelly's illustrative work beyond the immediate context of news reporting.

Masterpiece of Irish Life: Mass in a Connemara Cabin

Perhaps Aloysius O'Kelly's most celebrated work is Mass in a Connemara Cabin, painted around 1883. This large and detailed canvas depicts a Catholic Mass being celebrated within the humble confines of a peasant dwelling in the west of Ireland. At a time when Catholic religious practice was sometimes restricted or carried out discreetly, particularly in poorer areas lacking formal church buildings (or during periods of suppression), the painting captures a moment of profound faith and community resilience amidst poverty.

The painting is remarkable for its meticulous detail, showcasing O'Kelly's academic training under Gérôme. The textures of the stone walls, the thatched roof, the simple wooden furniture, and the varied garments of the congregation are rendered with precision. Yet, the work transcends mere technical skill; it conveys a palpable atmosphere of reverence and quiet devotion. The composition guides the viewer's eye towards the priest at the makeshift altar, while also giving individual attention to the faces and postures of the worshippers, young and old.

Mass in a Connemara Cabin was exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1884, a significant achievement for an Irish artist depicting an explicitly Irish theme. It was reportedly the only painting with an Irish subject shown at the Salon that year. Its exhibition brought O'Kelly considerable recognition. However, the painting's history took a curious turn; it disappeared from public view for nearly a century before being rediscovered hanging in a church in County Louth, Ireland. It was subsequently acquired by the National Gallery of Ireland, where it remains a key work in the collection of Irish art, admired alongside pieces by contemporaries like Walter Osborne and Nathaniel Hone the Younger. The painting stands as a powerful testament to O'Kelly's ability to merge social realism with deep cultural and religious significance.

The Lure of the East: O'Kelly the Orientalist

Following his experiences illustrating the conflict in Sudan, O'Kelly's fascination with North Africa and the Middle East deepened, leading to extensive travels in the region, particularly in Egypt, Algeria, and Morocco, during the 1880s and beyond. This phase of his career firmly places him within the Orientalist tradition, alongside his former teacher Gérôme and other prominent artists like Eugène Delacroix, John Frederick Lewis, and the American Frederick Arthur Bridgman.

Unlike some Orientalists who relied on studio props and romanticised stereotypes, O'Kelly's work often benefited from his direct observation and experiences as a correspondent. His paintings depicted bustling market scenes (souks), quiet courtyards, mosques, street life, and portraits of local people. He demonstrated a keen interest in capturing the effects of the intense North African light and colour, sometimes adopting a brighter palette and looser brushwork than seen in his more academic works, perhaps reflecting a subtle, ongoing dialogue with Impressionism.

His Egyptian scenes, often featuring views along the Nile or studies of ancient ruins, combined topographical accuracy with atmospheric effect. In Algeria and Morocco, he seemed particularly drawn to the vibrant life of the cities and the dignity of their inhabitants. While inevitably viewed through a Western lens, O'Kelly's Orientalist works often display a level of ethnographic interest and a less overtly sensationalised approach compared to some of his contemporaries, such as Ludwig Deutsch or Rudolf Ernst, known for their highly polished, almost photographic, depictions. This period added another significant dimension to his already diverse oeuvre.

Across the Atlantic: The American Years

Towards the end of the 19th century, possibly around the mid-1890s, Aloysius O'Kelly made another significant geographical shift, moving to the United States and settling primarily in New York City. The reasons for this move are not entirely clear but may have involved seeking new markets for his art, joining family members, or simply pursuing new experiences. He continued to work as an artist, exhibiting his paintings, including his popular Orientalist scenes, at venues like the National Academy of Design.

His time in America saw him adapt his subject matter to his new surroundings. While he continued to paint and sell works based on his Irish and North African experiences, he also began to depict American landscapes and potentially urban scenes, although this period of his work is less well-documented than his earlier phases. He painted coastal scenes in the Northeast and possibly views of New York City itself. It is conceivable he may have encountered the work of American Impressionists like Childe Hassam or urban Realists associated with the Ashcan School, such as Robert Henri or John Sloan, though the extent of any direct influence remains speculative.

Despite living in the United States for several decades until his death in 1941, O'Kelly maintained connections with Ireland and his Irish identity remained central to his artistic reputation. He continued to exhibit works with Irish themes and revisited Ireland periodically. His American years represent the final chapter in a life marked by extensive travel and adaptation, yet his artistic legacy remains most strongly tied to his powerful depictions of Ireland and his exotic renderings of the East.

Style and Technique: A Synthesis

Aloysius O'Kelly's artistic style is not easily categorised, primarily because he adapted his approach depending on his subject matter and purpose. At its core, his work is grounded in the academic tradition inherited from Gérôme, characterised by strong drawing, careful composition, and attention to detail. This is particularly evident in major works like Mass in a Connemara Cabin and many of his Orientalist paintings.

However, O'Kelly was not merely an academic painter. His engagement with Realism is clear in his unvarnished depictions of poverty and social conditions in Ireland and his observational approach during his travels. He sought to record the world around him, whether it was the hardship of an evicted Irish family or the daily rituals of a Cairo street market. This aligns him with the broader Realist movement that sought truthfulness over idealisation.

Furthermore, O'Kelly demonstrated sensitivity to light and colour that sometimes approached Impressionism, especially in his landscapes and outdoor scenes painted in Brittany, North Africa, and potentially America. While he rarely dissolved form completely in the manner of Monet, his palette could brighten considerably, and his brushwork become looser to capture fleeting atmospheric effects. His Orientalist works, in particular, often revel in the play of bright sunlight and deep shadow. His illustrative work, by necessity, focused on narrative clarity and strong composition, often emphasising dramatic moments or conveying social commentary effectively through visual means. His ability to synthesize these different elements – academic precision, Realist observation, atmospheric sensitivity, and narrative skill – defines his unique artistic identity.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For much of the 20th century, Aloysius O'Kelly remained a somewhat marginal figure in Irish art history. Several factors contributed to this relative obscurity. His peripatetic career meant he wasn't consistently associated with any single artistic movement or location for long periods. His stylistic diversity, moving between academic painting, realism, and illustration, perhaps made him difficult to pigeonhole for art historians focused on linear narratives of modernism. Furthermore, his long residence in the United States may have distanced him from the main currents of the Irish art scene in the early 20th century, which saw the rise of figures like Jack B. Yeats and William Orpen.

However, recent decades have witnessed a significant reassessment and rediscovery of O'Kelly's work. Exhibitions and scholarly research, particularly focusing on his Irish subjects and his role as a visual commentator on the Land War, have brought his contributions back into the spotlight. The rediscovery and acquisition of Mass in a Connemara Cabin by the National Gallery of Ireland was a pivotal moment in this revival. His connection to Van Gogh, through his illustrations, has also added another layer of interest for international scholars.

Today, O'Kelly is recognised as a highly skilled and versatile artist whose work provides invaluable insights into Irish social history, the complexities of Orientalism, and the life of a late 19th-century artist navigating a rapidly changing world. His ability to operate across different genres – painting and illustration – and engage with diverse cultural contexts marks him as a uniquely compelling figure. His paintings are now sought after by collectors and feature prominently in major Irish collections.

Conclusion: An Artist of Many Worlds

Aloysius C. O'Kelly's life and art embody a journey through diverse landscapes, cultures, and artistic styles. From the politically charged atmosphere of his Dublin youth to the academic rigour of Gérôme's Paris studio, the rustic charm of Brittany, the social turmoil of Land War Ireland, the exotic allure of North Africa, and the dynamic environment of New York, O'Kelly absorbed and reflected the varied worlds he inhabited. His legacy lies in his skillful synthesis of academic technique and realist observation, his empathetic portrayal of Irish life during a critical historical period, his contribution to the complex genre of Orientalism, and his work as a pioneering illustrator. While perhaps overshadowed at times by contemporaries who followed a more conventional path, O'Kelly's multifaceted career and compelling body of work secure his place as a significant and intriguing Irish artist whose paintings and illustrations continue to resonate with historical and artistic importance.