Alphonse Osbert stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure within the constellation of French Symbolism. Active during a period of profound artistic transformation at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, Osbert carved a unique niche for himself with his ethereal landscapes, mystical figures, and a distinctive use of color and light that became his hallmark. His journey from academic tradition to a deeply personal Symbolist vision reflects the broader currents of an era seeking to transcend materialism and explore the realms of dream, spirituality, and poetic suggestion.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

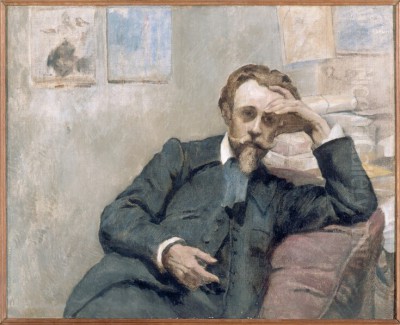

Born in Paris on March 23, 1857, into a prosperous bourgeois family, Alphonse Osbert's early life provided him with the stability and resources to pursue an artistic career. His father, a photographer and printing editor, likely exposed him to the visual arts from a young age. This comfortable background allowed him to enroll at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the bastion of academic art training in France.

At the École, Osbert studied under Henri Lehmann, a German-born painter known for his classical and religious subjects, himself a pupil of the great Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Lehmann's tutelage would have instilled in Osbert a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the traditional hierarchy of genres. During these formative years, Osbert shared his studies and even a studio with notable contemporaries who would go on to make their own marks on art history, including the pioneering Neo-Impressionist Georges Seurat and the Symbolist painter Edmond Aman-Jean. This early association with Seurat, in particular, would prove influential later in Osbert's career.

Initially, Osbert's artistic inclinations leaned towards a more conventional, naturalistic style. He was drawn to the dramatic intensity and rich chiaroscuro of Spanish Golden Age masters like Jusepe de Ribera, whose influence can be discerned in his earlier works. These pieces, often characterized by their darker palettes and robust forms, demonstrated technical skill but had yet to reveal the distinctive poetic sensibility that would later define his oeuvre.

The Pivotal Shift Towards Symbolism

The 1880s marked a period of intense artistic ferment in Paris. Impressionism had already challenged academic conventions, and a new generation was seeking different avenues of expression. Post-Impressionist movements were burgeoning, and Symbolism was emerging as a powerful literary and artistic force, reacting against the perceived superficiality of Realism and Impressionism's focus on fleeting visual phenomena. Symbolists aimed to convey ideas, emotions, and spiritual truths through suggestive imagery and metaphorical language.

For Osbert, this period was transformative. He began to move away from his earlier naturalistic and Spanish-influenced style, increasingly drawn to the ideals of Symbolism. A crucial catalyst for this shift was his encounter with the work and, subsequently, the friendship of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Puvis, older and highly respected, was a pivotal figure whose monumental, serene, and allegorical murals offered an alternative to both academicism and Impressionism. Puvis's simplified forms, muted colors, and emphasis on timeless, universal themes resonated deeply with Osbert and many other artists seeking a more spiritual and contemplative art.

By the late 1880s, Osbert had fully embraced Symbolism. He began to exhibit with avant-garde groups, including the Salon des Indépendants, and later, most significantly, at the Salon de la Rose+Croix. Founded by the eccentric Sâr Joséphin Péladan, the Salon de la Rose+Croix was a beacon for Symbolist artists dedicated to idealism, mysticism, and the rejection of materialism. Osbert became a prominent exhibitor, aligning himself with artists like Jean Delville, Carlos Schwabe, and Fernand Khnopff, who shared similar esoteric and spiritual concerns.

The Essence of Osbert's Symbolist Vision

Alphonse Osbert’s mature Symbolist style is characterized by its profound serenity, mystical atmosphere, and a highly personal iconography. He largely abandoned narrative or anecdotal subjects, focusing instead on evocative landscapes populated by solitary, often ethereal female figures – muses, priestesses, or personifications of abstract concepts like Evening, Silence, or Inspiration.

His landscapes are not specific locales but rather idealized, timeless settings: tranquil lakes reflecting twilight skies, sacred groves bathed in moonlight, or serene shores where the boundary between water and sky seems to dissolve. These settings serve as stages for contemplation and spiritual communion. The figures within them are typically static, absorbed in thought or reverie, their gestures minimal and their expressions enigmatic. They often appear as intermediaries between the earthly and the divine, embodying a sense of peace and otherworldly grace.

Water is a recurring motif in Osbert's work, symbolizing purity, reflection, and the unconscious. Trees, often slender and silhouetted against luminous skies, can suggest aspiration or a connection between earth and heaven. The moon, a quintessential Symbolist emblem, frequently appears, casting a soft, mysterious glow and evoking themes of dreams, introspection, and the feminine principle. Works like Muse du Soir (Muse of the Evening) or An Evening in Ancient Times perfectly encapsulate this dreamlike quality, where spectral muses inhabit landscapes bathed in an unearthly light.

The Palette of Dreams: Color and Light

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Osbert's art is his masterful use of color and light. He developed a signature palette dominated by blues, mauves, and violets, often accented with pale yellows or oranges, particularly in his depictions of sunsets and moonrises. This characteristic use of blue became so renowned that it was sometimes referred to as "Osbert blue." These cool, harmonious color schemes contribute significantly to the tranquil, meditative, and often melancholic mood of his paintings.

His handling of light is equally remarkable. Osbert was deeply interested in capturing the subtle gradations of twilight and moonlight, creating a soft, diffused luminescence that envelops his scenes. This fascination with crepuscular and nocturnal light earned him nicknames such as "the painter of the night" and "the painter of sunsets." He sought to depict not just the physical appearance of light, but its spiritual and emotional resonance, using it to evoke a sense of mystery and transcendence.

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, influenced by his former classmate Georges Seurat and other Neo-Impressionists like Paul Signac, Osbert began to incorporate elements of Pointillism into his technique. However, his application of this method was less rigidly scientific than that of Seurat or Signac. Osbert adapted Pointillism to serve his Symbolist aims, using small dabs of color not primarily for optical mixing in the scientific sense, but to enhance the vibrancy and luminosity of his surfaces, creating a shimmering, ethereal effect that perfectly suited his dreamlike visions. This technique allowed him to achieve a unique texture and a subtle vibration of color that further dematerialized his forms and heightened the otherworldly atmosphere of his work.

Key Artistic Circles and Influences

Osbert was an active participant in the Symbolist milieu of Paris. His involvement with the Salon de la Rose+Croix (1892-1897) placed him at the heart of the Symbolist movement. These Salons, organized by Péladan, were highly influential and controversial, promoting an art that was mystical, allegorical, and often infused with esoteric or religious themes. Osbert's serene and idealized visions were well-suited to Péladan's aesthetic agenda, and he exhibited regularly alongside artists such as Armand Point, Alexandre Séon, and the Belgian Symbolists Jean Delville and Fernand Khnopff.

Beyond the Rose+Croix, Osbert maintained connections with a wide circle of artists and writers. His friendship with Pierre Puvis de Chavannes remained a cornerstone of his artistic life, and Puvis's influence is palpable in Osbert's simplified compositions and his pursuit of a timeless, universal quality. He was also close to the Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, whose influential "Tuesday gatherings" were a hub for Symbolist writers and artists. Mallarmé's poetic ideals, emphasizing suggestion, musicality, and the evocation of mystery, paralleled Osbert's own artistic aims.

The influence of other Post-Impressionist painters can also be noted. While Seurat's Pointillism was a technical inspiration, the broader spiritual and decorative concerns of artists like Maurice Denis, a leading theorist of the Nabi group, also found echoes in Osbert's work. Denis, like Osbert, sought an art that transcended mere representation to express inner truths and spiritual feeling, famously stating that a painting, "before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order." This emphasis on the decorative and expressive qualities of art was shared by Osbert.

Other Symbolist painters whose work shares affinities with Osbert's include Odilon Redon, with his dreamlike imagery and exploration of the subconscious, and Gustave Moreau, whose richly detailed and enigmatic mythological scenes also delved into the symbolic. While Osbert's style was generally more serene and less overtly dramatic than Moreau's, they shared a common desire to imbue their art with deeper meaning. Even artists from other countries, like the Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin, known for his atmospheric and often melancholic landscapes, or the Viennese master Gustav Klimt, whose decorative symbolism and use of gold share a certain affinity with Osbert's pursuit of beauty and spiritual resonance, can be seen as part of the same broad European Symbolist current.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Throughout his career, Alphonse Osbert produced a consistent body of work that explored his characteristic themes and stylistic concerns. Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of his artistic vision.

La Chanson Eternelle (The Eternal Song), housed in the Petit Palais, Paris, is a quintessential Osbert. It depicts a lyre-playing muse by a tranquil body of water, bathed in the soft glow of twilight. The composition is balanced and harmonious, the colors predominantly cool blues and mauves, creating an atmosphere of profound peace and timelessness. The painting evokes a sense of music, poetry, and the enduring power of art.

Muse du Soir (Muse of the Evening) and An Evening in Ancient Times are other prime examples of his preferred subject matter. These works often feature solitary female figures, draped in classical attire, contemplating serene, crepuscular landscapes. The light is soft and diffused, the mood one of quiet introspection and mystical communion with nature. The figures are not portraits but archetypes, embodying the spirit of poetry, inspiration, or the contemplative soul.

His painting Inspiration showcases a figure, perhaps a poet or artist, receiving divine or natural inspiration, often symbolized by light or a celestial presence. These works underscore the Symbolist belief in art as a conduit for higher truths and spiritual insight.

While primarily a painter, Osbert also produced at least one known color lithograph, Inceste d’Ames et Minotaure (Incest of Souls and Minotaur). This work, with its more overtly mythological and potentially unsettling theme, suggests a less common facet of his artistic exploration, perhaps hinting at the darker, more complex psychological undercurrents that also characterized some Symbolist art, though his dominant mode remained one of serenity.

Public Commissions and Decorative Works

Osbert's artistic talents were not confined to easel painting. His style, with its emphasis on harmony, simplified forms, and evocative atmosphere, lent itself well to large-scale decorative projects. He received several important public commissions, allowing him to create murals that brought his Symbolist vision to a wider audience.

One of his most notable commissions was for the decoration of the Vichy Thermal Baths (Palais des Sources). Here, he created a series of allegorical paintings depicting themes related to water, healing, and nature, perfectly suited to the spa's function. These murals, with their serene figures and harmonious landscapes, aimed to create a calming and uplifting environment for visitors.

He also undertook decorative work for the town hall of Bourg-la-Reine and contributed to religious commissions, such as murals for a religious center in Genoa and for the St. Louis Church in Paris. These projects demonstrate the adaptability of his Symbolist aesthetic to different contexts, whether secular or sacred. In this, he followed the example of Puvis de Chavannes, who was a master of monumental decorative painting. Osbert's decorative works emphasized the integration of art with architecture, aiming for a total aesthetic experience that was both beautiful and spiritually resonant.

The "Silent Poet": Osbert's Unique Voice and Reception

Alphonse Osbert's art, with its quiet intensity and poetic sensibility, earned him a distinct reputation among his contemporaries. He was sometimes referred to as "the silent poet" or the "Alma artist" (Alma being a term associated with soul or spirit), reflecting the deeply spiritual and introspective nature of his work. Critics often praised his ability to evoke mood and atmosphere, his subtle harmonies of color, and the serene beauty of his compositions.

His participation in the Salons, particularly the Salon de la Rose+Croix and the Salon des Indépendants, ensured that his work was seen and discussed. He was generally well-regarded within Symbolist circles and by critics sympathetic to the movement's aims. His art offered a contemplative alternative to the more turbulent or decadent strains of Symbolism, focusing on themes of peace, harmony, and spiritual illumination.

However, like many Symbolist artists, Osbert's reputation experienced a decline in the early 20th century as new avant-garde movements like Fauvism, Cubism, and Surrealism came to dominate the art world. The introspective and often mystical concerns of Symbolism seemed out of step with the more radical formal innovations and the increasingly secular and materialist concerns of the modern era. Some later critics occasionally dismissed his work as overly "sweet" or "pious," finding its serenity perhaps lacking in the dramatic tension or intellectual rigor prized by modernism.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Alphonse Osbert continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, remaining true to his Symbolist vision even as artistic fashions changed. He passed away in Paris on August 11, 1939, on the cusp of another world war that would further transform the cultural landscape.

For several decades after his death, Osbert, like many of his Symbolist contemporaries, was largely overlooked by mainstream art history, which tended to prioritize the narratives of Impressionism and the major modernist movements. However, the latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century have witnessed a significant scholarly and curatorial reassessment of Symbolism. This revival of interest has brought renewed attention to artists like Osbert, recognizing their important contributions to the diverse tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century art.

Today, Alphonse Osbert is recognized as a distinctive and accomplished Symbolist painter. His works are held in numerous public collections, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Petit Palais in Paris. Exhibitions dedicated to Symbolism regularly feature his paintings, highlighting his unique ability to create images of profound tranquility and poetic beauty. His mastery of color and light, his consistent exploration of spiritual themes, and his creation of a highly personal and recognizable artistic world ensure his place in the history of French art.

Osbert in the Pantheon of Symbolism

When viewed within the broader context of European Symbolism, Alphonse Osbert occupies a specific and valuable position. While artists like Gustave Moreau explored complex mythologies with opulent detail, and Odilon Redon delved into the shadowy realms of dreams and the subconscious, Osbert offered a vision of Symbolism characterized by clarity, serenity, and a gentle, pervasive spirituality. His art is less about overt narrative or psychological drama and more about evoking a state of being – a contemplative stillness where the soul can connect with the eternal.

Compared to the more overtly mystical or esoteric Symbolism of artists like Jean Delville or Carlos Schwabe, Osbert's work is often more accessible, its beauty more immediately apparent. Yet, beneath the surface calm lies a deep engagement with the core tenets of Symbolism: the belief in an unseen reality, the importance of subjective experience, and the power of art to convey spiritual truths. His consistent use of a distinctive color palette and his focus on crepuscular light set him apart, creating a signature style that is instantly recognizable.

His connection to Puvis de Chavannes is crucial, placing him in a lineage of artists who sought a modern form of classicism, one that was imbued with symbolic meaning and decorative harmony. Like Puvis, Osbert aimed for an art that was timeless and universal, speaking to fundamental human aspirations for peace, beauty, and spiritual understanding.

Conclusion: A Painter of Luminous Dreams

Alphonse Osbert was more than just a "painter of the night" or a follower of Symbolist trends. He was an artist who, through a dedicated exploration of light, color, and poetic imagery, forged a unique visual language to express his deeply felt spiritual and aesthetic ideals. His paintings invite viewers into a world of tranquil beauty and quiet contemplation, offering a respite from the clamor of modern life and a glimpse into a realm of luminous dreams.

In an era of rapid change and artistic revolution, Osbert chose a path of serene introspection, creating an oeuvre that continues to resonate with its timeless appeal and its gentle insistence on the enduring power of beauty and the human spirit. His contribution to French Symbolism, characterized by its distinctive "Osbert blue," its ethereal figures, and its dreamlike landscapes, remains a testament to an artist who successfully translated his inner vision into a body of work that is both deeply personal and universally evocative. As art history continues to re-evaluate the diverse currents of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Alphonse Osbert's star shines with a quiet but persistent luminescence.