Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431–1506) stands as one of the most formidable and influential artists of the Italian Renaissance. Active primarily in Padua and Mantua, his career spanned a crucial period of artistic innovation. Mantegna's unique style, characterized by a profound engagement with classical antiquity, a rigorous application of perspective, and figures possessing sculptural solidity, left an indelible mark on the course of North Italian painting and beyond. His technical mastery, intellectual depth, and innovative spirit established him as a pivotal figure, bridging the gap between the early Renaissance's experimental fervor and the High Renaissance's classical synthesis.

Early Life and Training in Padua

Andrea Mantegna was born around 1431 near Vicenza, in Isola di Carturo, then part of the Republic of Venice. Information about his earliest years remains somewhat sparse, with some accounts suggesting humble origins, possibly involving time spent with shepherds or herdsmen, though the veracity of these tales is debated. What is certain is that Mantegna displayed remarkable artistic talent from a young age. This precocity caught the attention of Francesco Squarcione, a painter and art teacher in the bustling artistic center of Padua.

Around 1442, the young Mantegna entered Squarcione's workshop as an apprentice. Squarcione, known more for his collection of antiquities and his large studio than for his own artistic output, legally adopted Mantegna. Padua, at this time, was a vibrant hub of humanism and artistic activity, significantly influenced by the presence of Florentine masters like Donatello, whose powerful sculptures undoubtedly impacted the young Mantegna. Squarcione's workshop provided access to classical models and fostered an interest in Roman art, which would become a defining feature of Mantegna's work.

Mantegna quickly absorbed the lessons of his environment, developing exceptional skill. His independent talent soon became evident. By the age of 17, he had already established his own workshop, signaling a break from Squarcione, a separation that later involved legal disputes. One of his earliest major commissions was for the decoration of the Ovetari Chapel in the Church of the Eremitani in Padua, a project he worked on alongside other artists, including Niccolò Pizzolo. Tragically, these frescoes, depicting scenes from the lives of Saints James and Christopher, were largely destroyed by bombing in World War II, but surviving fragments and photographs attest to Mantegna's early mastery of complex compositions, anatomical accuracy, and dramatic perspective.

The Ovetari frescoes showcased Mantegna's burgeoning style: sharp, clear lines, figures imbued with a sense of gravity and realism reminiscent of classical sculpture, and a sophisticated understanding of spatial representation. His figures were solid, expressive, and rendered with meticulous attention to anatomical detail, setting a new standard for naturalism combined with classical dignity in Paduan art.

The Enduring Influence of Antiquity

Mantegna's fascination with the classical world was profound and lifelong, earning him the moniker of an "archaeological painter." This interest went far beyond mere stylistic borrowing; it was an intellectual engagement with the forms, motifs, and spirit of ancient Rome. His time in Padua, a city with Roman roots and a university fostering humanist scholarship, provided fertile ground for this passion. Squarcione's collection, though perhaps used somewhat unscrupulously by the master, gave Mantegna direct access to casts and fragments of classical sculpture.

This deep immersion in antiquity manifested clearly in his art. Mantegna meticulously studied Roman architecture, reliefs, and statuary, incorporating authentic details into his paintings. Triumphal arches, classical friezes, garlands, and inscriptions frequently appear in his backgrounds and decorative elements, lending his scenes a sense of historical weight and grandeur. He was among the first Renaissance artists to integrate Roman archaeological elements so thoroughly and accurately into landscape and narrative settings.

His figures often possess the gravitas and idealized forms of Roman statues. He even created paintings intended to mimic the appearance of ancient sculptures, known as bronzetti finti (fake bronzes), demonstrating his technical skill in simulating different materials and his deep appreciation for classical aesthetics. Works like the various depictions of Saint Sebastian exemplify this, often setting the martyred saint against a backdrop of meticulously rendered Roman ruins, transforming a religious subject into a meditation on the endurance of faith amidst the remnants of a powerful, pagan past. This classicizing tendency gave his work a distinctive, somewhat austere and statuesque quality.

Mastery of Technique: Perspective and Illusionism

Andrea Mantegna was a pioneer in the development and application of perspective techniques, contributing significantly to the Renaissance quest for realistic spatial representation. He possessed an extraordinary command of linear perspective, using converging lines to create convincing illusions of depth on a two-dimensional surface. His compositions are often characterized by a low viewpoint (di sotto in su), which enhances the monumentality of the figures and the grandeur of the architectural settings. This technique forces the viewer to look upwards, creating a sense of awe and drama.

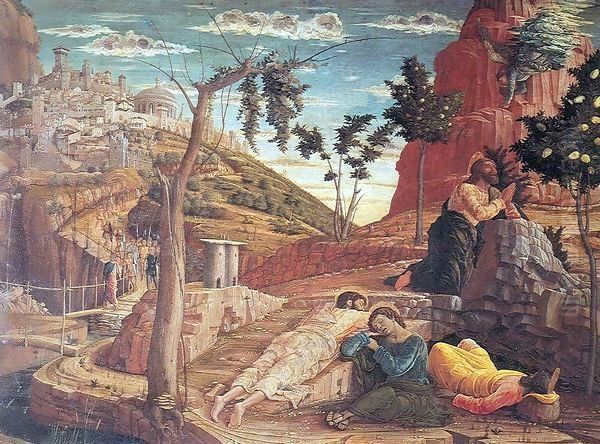

His experiments with foreshortening – the technique of depicting an object or human body in a picture so as to produce an illusion of projection or extension in space – were particularly daring. The most famous example is the Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan). This powerful and emotionally charged work shows the body of Christ laid out on a slab, viewed feet-first. The radical foreshortening, while perhaps not perfectly anatomically accurate by modern standards, was a stunning display of technical virtuosity for its time, confronting the viewer with the stark reality of Christ's death in an intensely personal and visceral way.

Mantegna's figures are notable for their sculptural quality, achieved through sharp outlines, meticulous modeling of form, and a clear, almost harsh light that defines volumes precisely. His attention to anatomical accuracy was remarkable, reflecting the growing interest in scientific observation during the Renaissance. Even in complex group scenes, each figure maintains a distinct physical presence. The source material mentions his depiction of the Madonna in the Lamentation as showcasing anatomical understanding, highlighting his focus on realistic portrayal even within highly emotional contexts.

He worked proficiently in various media. While renowned for his frescoes, he was also a master of tempera painting, often on canvas, which allowed for fine detail and luminous color. Some sources mention his use of distemper (glue-size medium) for works like the Adoration of the Magi, a technique suitable for large canvases and yielding a matte finish, differing from the gloss of oil paint which was becoming increasingly popular in Venice, partly through the influence of artists like Antonello da Messina.

The Court Painter in Mantua

In 1460, Mantegna accepted the invitation of Ludovico III Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, to become the official court artist. This move marked a significant shift in his career, placing him at the center of a sophisticated and ambitious court culture. He would serve the Gonzaga family for the rest of his life, working for Ludovico, Federico I, and Francesco II Gonzaga, as well as the highly cultured Isabella d'Este, wife of Francesco II. His position provided him with financial security (though records suggest occasional disputes over payment) and prestigious commissions.

His most celebrated work in Mantua is the decoration of the Camera degli Sposi (literally "Bridal Chamber," though more accurately a reception room) in the Ducal Palace, completed around 1474. This fresco cycle is a landmark of Renaissance art. Mantegna transformed the small room into a pavilion, blurring the lines between painting and reality. On the walls, he depicted scenes of the Gonzaga family and court life with remarkable naturalism and detail, offering an intimate glimpse into the world of his patrons.

The ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi features a breathtaking example of trompe l'oeil (trick of the eye) illusionism. Mantegna painted an oculus, seemingly open to the sky, with figures and putti peering down into the room from a balustrade. This innovative use of di sotto in su perspective created a startling sense of spatial depth and became highly influential, inspiring later artists like Correggio in his dome frescoes in Parma.

Another major project for the Gonzaga was the Triumphs of Caesar, a series of nine larger-than-life paintings on canvas executed primarily in tempera (distemper). Created over many years (c. 1484–1492), these monumental works depict a Roman triumphal procession celebrating Julius Caesar's victories. Based on classical texts and archaeological evidence, the Triumphs are a powerful testament to Mantegna's antiquarian knowledge and his ability to orchestrate complex, dynamic compositions filled with figures, animals, and elaborate paraphernalia. They were designed to be viewed as a continuous procession and represent one of the most ambitious attempts to recreate the splendor of ancient Rome.

Other important works from his Mantuan period include the Madonna della Vittoria, commissioned by Francesco II Gonzaga to commemorate his contested victory at the Battle of Fornovo, and mythological paintings for Isabella d'Este's studiolo, such as Parnassus (Il Parnaso) and Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue (Trionfo della Virtù). These later works often display a greater richness of color and a slightly softer style, perhaps reflecting contact with Venetian painting, while still retaining Mantegna's characteristic clarity and classical references.

Pioneer in Printmaking

Beyond his achievements in painting and fresco, Andrea Mantegna played a crucial role in the early history of printmaking in Italy. He was one of the first major Italian artists to fully embrace engraving as a medium for artistic expression and dissemination. While the exact extent of his personal involvement in cutting the plates is debated by scholars, he undoubtedly designed numerous engravings and oversaw a workshop that produced high-quality prints based on his compositions.

Mantegna likely recognized the potential of engraving to replicate his designs accurately and distribute them to a wider audience, including fellow artists across Europe. His prints, characterized by their strong outlines, parallel hatching for shading (mimicking his drawing style), and classical subject matter, were highly sought after. Subjects included scenes from the Triumphs of Caesar, mythological themes like the Battle of the Sea Gods, and religious images such as the Entombment.

His engagement with printmaking was not without challenges. The source material notes his potential concern about piracy, suggesting he may have preferred to keep production within his own control to protect his artistic inventions. Regardless, his prints were immensely influential, helping to spread his style and classical motifs far beyond Mantua. Artists like Albrecht Dürer were known to have studied and copied Mantegna's engravings, demonstrating their significant impact on the development of printmaking and artistic exchange in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. He led one of the earliest significant printmaking workshops in the Venice region, contributing to the medium's rise as a major art form.

Relationships, Rivalries, and Influences

Mantegna's career unfolded within a network of artistic relationships, patronage connections, and intellectual currents. His early training under Squarcione was foundational, providing access to classical models, though the relationship eventually soured. Mantegna felt exploited by his adoptive father, leading to disputes and, according to the provided text, a lawsuit filed by Mantegna against Squarcione as late as 1484 over financial matters related to his early work, highlighting the sometimes contentious nature of workshop practices.

Perhaps the most significant artistic relationship was with the Bellini family of Venice. Around 1453, Mantegna married Nicolosia Bellini, daughter of Jacopo Bellini and sister of the prominent painters Gentile and Giovanni Bellini. This connection fostered a rich artistic dialogue between Mantegna's rigorous, linear, and classicizing style and the burgeoning Venetian school's emphasis on color, light, and atmosphere, particularly evident in the work of Giovanni Bellini. While distinct in their approaches – Mantegna prioritizing drawing and sculptural form, Bellini exploring painterly effects – they undoubtedly influenced each other. Early works by Giovanni Bellini show a clear debt to Mantegna's compositional structure and figure types, while some of Mantegna's later works exhibit a softer modeling and richer palette possibly influenced by Venetian trends. Despite the family tie and mutual respect, an element of artistic rivalry likely existed between these leading figures of North Italian art.

His long tenure at the Gonzaga court involved close collaboration with his patrons, particularly Ludovico III and later Francesco II Gonzaga and Isabella d'Este. These patrons provided the commissions and resources for some of his most ambitious projects, like the Camera degli Sposi and the Triumphs of Caesar. His interactions were not limited to patrons; he also moved within humanist circles in both Padua and Mantua, engaging with scholars and antiquarians who shared his passion for classical antiquity. These interactions provided intellectual stimulus and informed the content and accuracy of his classically themed works.

Later Life and Personal Challenges

Mantegna's later years, despite his continued artistic activity and esteemed position at the Mantuan court, were marked by personal difficulties. The source material mentions significant hardships, including the exile of his son, Francesco Mantegna (also a painter), who incurred the displeasure of the Marquis Francesco II Gonzaga. This event undoubtedly caused Mantegna considerable distress.

Furthermore, he experienced financial worries, particularly noted after the death of his wife, Nicolosia. While court artists received stipends, payments could be irregular, and managing a large household and workshop involved significant expense. A poignant anecdote relates his deep sorrow over having to sell a cherished piece from his personal collection – a Roman bust identified as Faustina – to Isabella d'Este to alleviate financial pressure shortly before his death. This incident underscores both his passion for antiquity and the material challenges he faced even as a renowned master.

Andrea Mantegna died in Mantua on September 13, 1506, at the age of 75. He was buried in the Basilica di Sant'Andrea in Mantua, a church designed by another great Renaissance artist, Leon Battista Alberti. A funerary chapel dedicated to him was established there, featuring decorations by his sons and possibly Correggio, and containing a striking bronze bust believed to be a self-portrait or close likeness. His death marked the end of a long and immensely productive career that had profoundly shaped the art of the Renaissance.

Major Works and Artistic Significance

Andrea Mantegna's oeuvre includes some of the most iconic images of the Quattrocento. His major works consistently demonstrate his core artistic concerns: classical inspiration, perspective mastery, and sculptural form.

The Ovetari Chapel frescoes (c. 1448-1457, Padua, largely destroyed) were his first major public commission, establishing his reputation for monumental narrative painting and innovative perspective.

The San Zeno Altarpiece (1457-1459, Verona) is a key work from his Paduan period, showcasing his mature style before moving to Mantua. Its unified architectural framework and classically inspired figures had a significant impact on Veronese art.

The Camera degli Sposi (c. 1465-1474, Mantua) remains his most famous fresco cycle, celebrated for its illusionistic ceiling oculus and its intimate yet formal portrayal of the Gonzaga court. It set a new standard for secular decoration and illusionistic painting.

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1480, Milan) is a work of startling emotional power and technical bravura, renowned for its dramatic foreshortening and stark realism.

The Triumphs of Caesar (c. 1484-1492, Hampton Court Palace, London) represent his most ambitious engagement with classical antiquity, a monumental series reconstructing a Roman procession with archaeological detail and dynamic composition.

Saint Sebastian (multiple versions, e.g., Louvre, Paris; Ca' d'Oro, Venice; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) showcases his classicizing figure style and his use of Roman ruins as evocative settings.

The Madonna della Vittoria (1496, Louvre, Paris) is a grand votive altarpiece, rich in symbolism and detail, commissioned by Francesco II Gonzaga.

Paintings for Isabella d'Este's studiolo, including Parnassus and Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue (c. 1497-1502, Louvre, Paris), demonstrate his skill in complex allegorical and mythological subjects.

Works like the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Adoration of the Magi (various versions) combine religious narrative with his characteristic sharp detail, classical elements, and often innovative perspectives, such as the di sotto in su viewpoint mentioned for the Adoration of the Shepherds.

These works collectively illustrate Mantegna's artistic journey and his consistent dedication to intellectual rigor, technical precision, and the revival of classical ideals within a Christian context.

Influence and Enduring Legacy

Andrea Mantegna's impact on the art world was immediate and long-lasting. His rigorous style, mastery of perspective, and profound engagement with antiquity influenced generations of artists, both in Italy and Northern Europe. His brother-in-law, Giovanni Bellini, absorbed aspects of his compositional structure and figure drawing early in his career, even as he developed his own distinct Venetian style.

Leonardo da Vinci, though representing a different artistic temperament, certainly knew Mantegna's work, and aspects of Mantegna's realism and anatomical study may have resonated with Leonardo's own scientific interests. The Ferrarese school of painters, including Cosmè Tura and Francesco del Cossa, also shows affinities with Mantegna's sharp linearity and expressive intensity. His influence extended to Venice, impacting artists like Giorgione and the young Titian.

Perhaps most significantly, Mantegna's work, particularly his engravings, reached Northern Europe and profoundly affected Albrecht Dürer. Dürer traveled to Italy and greatly admired Mantegna's work, copying his prints and absorbing his classical motifs and compositional ideas. This interaction was crucial for transmitting Italian Renaissance innovations northward. Later artists, such as Correggio, were directly inspired by his illusionistic ceiling paintings. Even Baroque masters like Caravaggio, known for dramatic realism, arguably owe a debt to the unflinching, sometimes harsh, naturalism found in works like Mantegna's Lamentation. His influence can also be traced in the work of Raphael and later artists who studied his approach to classical themes and monumental composition. His sons, Ludovico and Francesco Mantegna, continued his workshop tradition, though without achieving his level of genius. Even Rembrandt owned prints by Mantegna, attesting to his long-term relevance.

Beyond specific artists, Mantegna's legacy lies in his elevation of the intellectual status of the artist, his pioneering role in integrating archaeological knowledge into painting, and his relentless pursuit of technical mastery in perspective and representation. His work continues to be studied for its formal power, its historical richness, and its unique blend of austerity and intensity. The source material also notes his influence on modern art and literature, particularly regarding the aesthetic appreciation of fragments and classical ruins, suggesting his vision resonates even today.

Commemoration and Remembrance

Andrea Mantegna's importance was recognized during his lifetime and has been celebrated posthumously. His burial in a dedicated chapel within Alberti's Basilica di Sant'Andrea in Mantua serves as a permanent monument. The city of Mantua, where he spent the majority of his productive career, preserves significant sites associated with him.

The Casa del Mantegna (Mantegna's House) in Mantua stands as a unique architectural testament. Likely designed by the artist himself around 1476, this building features a striking plan centered around a circular courtyard within a square structure, reflecting Renaissance ideals of geometric harmony derived from classical principles. Today, it serves as a cultural venue, hosting exhibitions and events, keeping his memory alive in the city he served for so long.

His artistic legacy is primarily preserved in the museums and collections that house his paintings and prints worldwide. Major retrospective exhibitions have been organized to honor his contributions, such as those held in Mantua, Verona, and Padua in 2006 (marking the 500th anniversary of his death) and subsequent shows like one in 2016, allowing new generations to experience the power and innovation of his art directly. These events underscore his enduring status as one of the foundational masters of the Italian Renaissance, whose work continues to command respect and fascination.

Conclusion

Andrea Mantegna was more than just a painter; he was an artistic innovator, an antiquarian scholar translated into visual form, and a master technician. His unwavering commitment to perspective, his profound dialogue with classical antiquity, and the sculptural power of his figures carved out a unique and influential path in Renaissance art. From the vibrant intellectual environment of Padua to the sophisticated court of the Gonzaga in Mantua, Mantegna synthesized humanistic learning with artistic practice, creating works of enduring power and intellectual depth. His influence radiated outwards through his paintings and engravings, shaping the course of art in Italy and beyond. He remains a towering figure, embodying the ambition, rigor, and transformative spirit of the Italian Renaissance.