Introduction: A Bridge Between Heaven and Earth

Fra Angelico, born Guido di Pietro, stands as a pivotal figure in the transition from the late Gothic period to the Early Italian Renaissance. Active primarily in Florence and Rome during the first half of the 15th century, he was unique among his contemporaries for being both a highly innovative painter and a devout Dominican friar. His art, characterized by its luminous color, serene figures, and profound spiritual depth, earned him the posthumous nickname "Angelico," the Angelic One. His works served not only as decoration but as powerful tools for contemplation and religious instruction, embodying the fusion of artistic advancement with unwavering faith that marked a significant current within the Renaissance. He is celebrated for his mastery of fresco and tempera, his sensitive portrayal of religious narratives, and his ability to imbue traditional subjects with a new sense of naturalism, light, and spatial coherence, influencing generations of artists who followed.

Early Life and Religious Calling in Tuscany

Guido di Pietro was born near Vicchio, in the Mugello region of Tuscany, Italy. The exact year of his birth remains a subject of scholarly debate, with sources suggesting dates ranging from around 1387 to, more commonly cited, about 1395. Little is definitively known about his early training, though his initial style suggests an apprenticeship within the late Gothic tradition, possibly influenced by manuscript illumination, a craft practiced by his brother Benedetto. The Florentine artistic environment, already vibrant with the innovations of sculptors like Lorenzo Ghiberti and Donatello, and soon to be revolutionized by the painter Masaccio, would undoubtedly have shaped his formative years.

A defining moment came around 1407, when Guido, along with his brother, entered the Dominican Order. He initially joined the observant convent at Fiesole, a town overlooking Florence. This decision was profound, shaping not only his life but the very essence of his art. The Dominican Order, known for its emphasis on preaching and theological study, provided a framework within which his artistic talents could be channeled towards expressing religious truths. Life as a friar involved prayer, study, and adherence to the rules of the order, principles that seem deeply reflected in the clarity, order, and piety evident in his paintings.

The Artist's Names: From Guido to Beato Angelico

Throughout his life and after his death, the artist known as Fra Angelico was referred to by several names, reflecting his journey from layman to revered friar-painter. Born Guido di Pietro, his entry into the Dominican Order marked the first significant change. Upon taking his vows, likely sometime between 1418 and 1421, he adopted the name Fra Giovanni da Fiesole – Brother John of Fiesole. "Fra" is the Italian abbreviation for "frater," meaning brother, signifying his status as a friar. This remained his official religious name for many years.

The name by which he is most famously known, Fra Angelico (Brother Angelic), appears to have gained currency after his death. It was likely bestowed upon him by contemporaries and later writers, notably the 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari, in recognition of the sublime, heavenly quality of his paintings and his own reputed piety and gentle nature. Vasari described him as a man of simple and holy habits, suggesting his art was a direct reflection of his virtuous character.

Finally, he is also known as Beato Angelico (the Blessed Angelico). This title reflects his reputation for sanctity, which culminated in his official beatification by Pope John Paul II in 1982. This act formally recognized his holy life and declared him the patron saint of Catholic artists. Thus, the progression of his names mirrors his evolution: a layman named Guido, a friar named Giovanni, an artist celebrated as Angelico, and a figure revered as Beato.

Artistic Development and Florentine Influences

Fra Angelico's artistic journey began rooted in the International Gothic style, prevalent in Florence during the early 15th century. This style, exemplified by artists like Lorenzo Monaco and Gentile da Fabriano, emphasized elegant lines, rich decorative patterns, and a certain ethereal quality, often detached from naturalistic representation. Angelico's early works, particularly his manuscript illuminations and smaller panel paintings, show mastery of this delicate and ornate aesthetic, characterized by graceful figures and brilliant, jewel-like colors.

However, living and working in Florence placed Fra Angelico at the epicenter of the burgeoning Renaissance. He could not ignore the revolutionary developments happening around him. The architect Filippo Brunelleschi was codifying linear perspective, creating mathematically structured, illusionistic spaces. Sculptors like Donatello were infusing their figures with unprecedented psychological depth and physical realism. Most importantly for Angelico, the painter Masaccio, in his frescoes for the Brancacci Chapel (completed by 1428), demonstrated a powerful new approach combining realistic human figures, dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and coherent perspectival space.

Fra Angelico absorbed these innovations selectively, integrating them into his own deeply spiritual vision. He did not simply abandon his Gothic training but rather synthesized it with the new Renaissance principles. His figures gained volume and solidity, his settings acquired logical spatial depth through the application of perspective, and his use of light became more sophisticated, employed not just for illumination but also to enhance the spiritual atmosphere and emotional resonance of his scenes. The Linaiuoli Altarpiece (1433), commissioned by the Flax Workers' Guild, is often cited as an early example where the influence of Masaccio's monumental figures and Donatello's sculptural forms becomes apparent, albeit framed within a more traditional, elaborate Gothic structure.

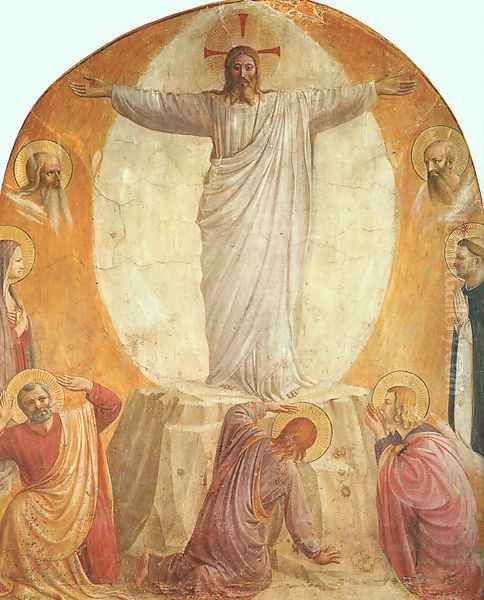

The San Marco Frescoes: Painting as Prayer

Perhaps Fra Angelico's most celebrated achievement is the fresco cycle decorating the Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence. Around 1436, the convent, recently transferred to the Dominicans of Fiesole, underwent extensive rebuilding funded by Cosimo de' Medici. Fra Angelico and his workshop were commissioned to adorn the newly constructed spaces – the cloister, the chapter house, the corridors, and significantly, the individual cells of the friars – with devotional images. This project occupied him for nearly a decade, from the late 1430s into the mid-1440s.

The San Marco frescoes are remarkable for their integration with the monastic environment and their intended function as aids to meditation and prayer for the resident friars. Unlike public commissions designed to impress or instruct a broad audience, many of these works, particularly those in the cells, possess an intimate, contemplative quality. They are characterized by simplified compositions, a restrained palette often dominated by ethereal light and soft colors, and figures that convey profound piety and spiritual intensity with minimal gestures.

Among the most famous works at San Marco is the Annunciation fresco located at the top of the dormitory stairs, greeting the friars as they ascended. Its serene beauty, logical perspective within the depicted cloister, and the gentle interaction between the Virgin Mary and the Archangel Gabriel perfectly encapsulate Angelico's mature style. Other notable frescoes include the large Crucifixion with Saints in the Chapter House, a complex theological statement featuring numerous Dominican saints, and the individual cell frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Christ, such as Noli Me Tangere, the Transfiguration, and the Mocking of Christ. Each image was carefully chosen to inspire contemplation on key aspects of Christian doctrine and the life of Christ, tailored to the spiritual needs of the monks.

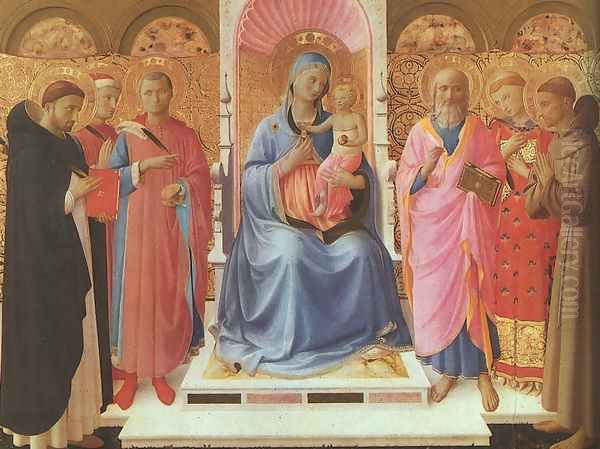

Major Panel Paintings and Altarpieces

While renowned for his frescoes, Fra Angelico was also a prolific master of panel painting, creating numerous altarpieces and smaller devotional works throughout his career. These works, executed primarily in tempera on wood panels, often display a greater richness of detail and intensity of color than his frescoes, reflecting the different demands and possibilities of the medium. His skill as a miniaturist, likely honed early in his career, is evident in the exquisite rendering of fabrics, architectural elements, and landscape backgrounds.

The Linaiuoli Altarpiece (1433), mentioned earlier, is a key work. Its central panel depicts a majestic Madonna and Child enthroned, flanked by saints on the wings. While the overall structure retains elements of a traditional polyptych, the central figures possess a new monumentality and spatial presence influenced by Masaccio. The predella panels below, depicting scenes from the life of St. Mark, showcase Angelico's narrative skill and delicate touch.

Another significant work is the Deposition from the Cross, originally commissioned from Lorenzo Monaco for the Strozzi Chapel in Santa Trinita, Florence, but largely completed by Fra Angelico after Monaco's death around 1425. Angelico masterfully integrated his style with Monaco's initial design, creating a poignant and compositionally sophisticated scene. The Annalena Altarpiece (c. 1437-1440), one of the first examples of a rectangular sacra conversazione (holy conversation) format, depicts the Madonna and Child surrounded by saints in a unified architectural space, marking a departure from the compartmentalized polyptych.

His Coronation of the Virgin, existing in versions now in the Uffizi and the Louvre, presents a celestial vision filled with light, harmonious color, and ranks of adoring saints and angels, embodying the heavenly bliss associated with his art. The Adoration of the Magi, a circular painting (tondo) now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., is a fascinating work believed to be a collaboration between Fra Angelico and another leading Florentine painter, Filippo Lippi. It combines Angelico's characteristic grace and luminous color with Lippi's more robust and earthly figure style.

Work in Rome and Later Career

Fra Angelico's fame extended beyond Florence, leading to prestigious commissions in other Italian cities, most notably Rome. In 1445, Pope Eugene IV summoned him to the Vatican to decorate the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament (later destroyed). This papal patronage continued under Pope Nicholas V, for whom Angelico, assisted by his pupil Benozzo Gozzoli, frescoed the Niccoline Chapel between approximately 1447 and 1449. These frescoes, depicting scenes from the lives of St. Stephen and St. Lawrence, survive today and showcase Angelico's mature style adapted to the grandeur of a papal commission. The compositions are more complex, the figures more numerous, and the architectural settings more elaborate than many of the San Marco works, demonstrating his versatility.

During this period, he also undertook work in Orvieto Cathedral, beginning frescoes in the Chapel of San Brizio in the summer of 1447, again with Gozzoli's assistance. They completed the vault segments depicting Christ in Judgment and Prophets, but the project was left unfinished by Angelico. It would later be famously completed by Luca Signorelli.

Fra Angelico served a term as Prior of the San Marco convent in Florence from 1449 to 1452, demonstrating that his artistic activities did not preclude him from fulfilling his religious duties. He returned to Rome sometime after this, possibly to work on further commissions. It was in the Dominican convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome that Fra Angelico died on February 18, 1455. His tomb, with a carved effigy, remains in the church today, a testament to the high esteem in which he was held even during his lifetime.

Artistic Style and Techniques: Light, Color, and Serenity

Fra Angelico's art is defined by a unique synthesis of late Gothic grace and Early Renaissance innovation, all infused with a profound spirituality. His most distinctive characteristic is perhaps his handling of light and color. He used clear, luminous hues, often employing expensive pigments like lapis lazuli for brilliant blues and gold leaf for divine radiance, reminiscent of manuscript illumination. His light is often soft and diffused, creating an atmosphere of serene divinity rather than harsh, dramatic contrasts. This light defines forms gently, enhances the purity of his colors, and contributes significantly to the overall spiritual mood of his works.

While aware of the principles of linear perspective being developed by Brunelleschi and employed by Masaccio, Angelico utilized them selectively. He created believable, ordered spaces, particularly evident in architectural settings like the cloister in the San Marco Annunciation. However, his primary goal was not scientific accuracy but spiritual expression. Perspective served to enhance the clarity and harmony of the composition, drawing the viewer into the sacred narrative.

His figures are typically graceful and idealized, conveying piety, humility, and divine bliss through subtle expressions and gestures. While influenced by Masaccio's realism, Angelico's figures retain an ethereal quality; they are solid and occupy space, yet seem imbued with an otherworldly serenity. He excelled at depicting narrative, simplifying complex stories into clear, easily readable compositions. Even in scenes of suffering, like the Crucifixion or the Mocking of Christ, there is an underlying sense of divine order and redemptive purpose. His attention to detail, whether in the delicate rendering of an angel's wing, the pattern on a robe, or the flowers in a meadow, adds richness without detracting from the overall spiritual focus. He worked masterfully in both fresco, suited for large-scale narrative cycles, and tempera on panel, allowing for finer detail and richer color saturation.

Religious Devotion and Artistic Practice

It is impossible to separate Fra Angelico the artist from Fra Giovanni the Dominican friar. His deep personal faith permeated his life and work. Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, famously recounted Angelico's piety, stating that he never took up his brushes without first offering a prayer and that he wept when painting a Crucifixion. Vasari also claimed Angelico believed his inspiration came directly from God, and thus he never altered or reworked a painting once finished.

While Vasari's account may contain elements of hagiography, it reflects the widely held perception of Angelico's profound devotion. His art was not merely a profession but a form of worship and preaching, a way to make visible the divine truths central to his Dominican vocation. The primary purpose of his paintings, especially those within monastic settings like San Marco, was to aid contemplation and foster devotion. The clarity, serenity, and spiritual intensity of his works were intended to lift the viewer's mind towards God.

This deep integration of faith and art is perhaps what gives his work its unique character. Unlike some contemporaries who explored more secular themes or focused primarily on technical innovation, Angelico consistently placed his considerable artistic skills in the service of religious expression. His paintings radiate a sense of conviction and sincerity that transcends mere technical proficiency, reflecting the beliefs of the man who created them. This perceived holiness contributed significantly to his "Angelic" reputation.

Collaborations and Workshop Practice

Like most successful artists of the Renaissance, Fra Angelico maintained an active workshop to assist him with the numerous commissions he received. Running a workshop was standard practice, allowing artists to undertake large-scale projects like fresco cycles and altarpieces efficiently. Assistants would help with preparing surfaces, grinding pigments, transferring designs (cartoons), and painting less critical areas under the master's supervision.

The most significant collaborator and pupil to emerge from Angelico's workshop was Benozzo Gozzoli. Gozzoli worked closely with Angelico on major projects, including the San Marco frescoes and the commissions in Rome (Niccoline Chapel) and Orvieto. Gozzoli absorbed much of Angelico's style but developed his own distinct manner, characterized by a greater love for anecdotal detail, decorative richness, and lively narrative, as seen in his famous frescoes in the Magi Chapel of the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence.

The collaboration with Filippo Lippi on the Adoration of the Magi tondo represents a partnership between two leading masters with distinct styles. Lippi, also a friar (Carmelite) though of a very different temperament, brought a more worldly robustness and psychological realism that contrasts interestingly with Angelico's serene grace in the finished work. Other artists, like the illuminator Zanobi Strozzi, are also sometimes associated with Angelico's circle or workshop, particularly in the production of manuscripts and smaller panels. Identifying the precise contributions of workshop hands in Angelico's larger projects remains a subject of art historical study, but the overall design and spiritual vision clearly bear the master's unmistakable imprint.

Anecdotes, Legends, and Mysteries

Fra Angelico's life, marked by piety and artistic dedication, has naturally attracted certain legends and interpretations over the centuries. Vasari's accounts of his prayerful habits and refusal to alter paintings contribute to the image of an artist guided solely by divine inspiration. While reflecting his genuine devotion, these stories likely simplify the complex reality of artistic creation, which involves skill, planning, and revision.

Another anecdote, also reported by Vasari, claims that Pope Nicholas V offered Fra Angelico the prestigious position of Archbishop of Florence, but the humble friar declined, recommending Fra Antonino Pierozzi instead (who did become Archbishop and later a saint). While this story highlights Angelico's reputed humility, its historical accuracy is debated among scholars; there is no contemporary documentation to confirm the offer or refusal. It remains part of the lore surrounding his saintly character.

More esoteric interpretations have occasionally surfaced. Some modern sources have attempted to link Fra Angelico's imagery, perhaps his depictions of angels or allegorical figures, to archetypes found in Tarot cards, suggesting hidden layers of meaning related to fate or mysticism. Such interpretations, however, lack strong historical grounding and are generally considered speculative, far removed from the documented context of Angelico's orthodox Dominican faith and the primary devotional function of his art. The true "mystery" of Fra Angelico lies less in hidden symbols and more in his extraordinary ability to translate profound spiritual feeling into visual form with such clarity and beauty.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

Fra Angelico's position in art history is secure as one of the leading masters of the Early Italian Renaissance. Art historians universally praise his technical skill, particularly his mastery of color and light, and his innovative role in synthesizing the elegance of the International Gothic with the burgeoning realism and spatial logic of the Renaissance. He is seen as a crucial figure who navigated this transition, creating a style that was both forward-looking and deeply rooted in spiritual tradition.

His influence on subsequent generations of artists was significant. His most direct follower was Benozzo Gozzoli, who carried aspects of his style throughout Central Italy. Filippo Lippi's work also shows dialogue with Angelico's art. Some scholars suggest his clarity of light and form may have impacted painters like Piero della Francesca, another giant of the Early Renaissance known for his serene compositions and mastery of perspective and light. His emphasis on devotional clarity and gentle piety resonated particularly within religious art, influencing painters in Florence and beyond, including Umbrian artists like Perugino.

Twentieth-century art historians like Bernard Berenson and John Pope-Hennessy wrote extensively on Fra Angelico, solidifying his reputation and analyzing his stylistic development and contributions. Berenson admired his ability to convey spiritual significance, while Pope-Hennessy provided rigorous studies of his chronology and works. Angelico is consistently lauded for achieving a perfect balance between artistic innovation and profound religious sentiment. His work is admired not just for its historical importance but for its enduring aesthetic appeal and spiritual resonance. The official beatification in 1982 served as a modern affirmation of the unique blend of artistic genius and personal sanctity that defined his life and work.

Conclusion: The Enduring Light of Fra Angelico

Fra Angelico, Guido di Pietro, remains a luminous figure in the history of art. As both a Dominican friar and a master painter, he occupied a unique space in the vibrant world of Quattrocento Florence. He embraced the artistic innovations of his time – perspective, naturalism, the study of light – but always subordinated them to his primary goal: the expression of divine truth and the fostering of religious devotion. His frescoes in San Marco stand as an unparalleled testament to the power of art to serve contemplation, while his altarpieces shine with exquisite color and serene grace.

He was an artist who truly painted his prayers, translating the core tenets of his faith into images of breathtaking beauty and clarity. His influence extended through his pupils and contemporaries, contributing significantly to the course of Renaissance painting. More than five centuries after his death, the works of Beato Angelico continue to inspire awe and reverence, offering viewers a glimpse into a world illuminated by divine light and profound peace. He remains not just a pivotal figure in art history, but a timeless master of spiritual expression.