Lorenzo Monaco, born Piero di Giovanni around 1370, stands as one of the most significant and distinctive painters of the late Gothic period in Italy, particularly in Florence. His art, characterized by its lyrical lines, vibrant spirituality, and exquisite use of color and gold, represents the pinnacle of the International Gothic style as it transitioned towards the nascent Renaissance. Though he remained largely faithful to the elegant, courtly aesthetics of the Gothic tradition, his work possesses a profound emotional depth and innovative compositional sense that secured his place as a pivotal figure in Florentine art. His adopted name, Lorenzo Monaco, meaning "Lorenzo the Monk," reflects a crucial aspect of his identity and career, deeply intertwined with the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence.

Early Life and Monastic Vows: Piero di Giovanni Becomes Lorenzo Monaco

The precise birthplace of Piero di Giovanni is a subject of some scholarly debate, with Siena being a strong possibility due to certain Sienese characteristics in his early style. However, it is certain that by his youth, he was in Florence, the bustling artistic and commercial heart of Tuscany. It was in Florence, around 1390 or 1391, that Piero di Giovanni made a life-altering decision: he entered the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli. This esteemed religious house was not only a center of spiritual life but also a renowned hub for manuscript illumination and other artistic endeavors.

Upon taking his vows, Piero di Giovanni adopted the religious name Lorenzo, to which "Monaco" (the Monk) was appended, thus becoming Lorenzo Monaco. He progressed within the monastic hierarchy, being recorded as a subdeacon in 1392 and ordained as a deacon in 1396. While he remained a monk for the rest of his life, his artistic calling was too strong to be confined solely within the cloister walls. By the early 15th century, Lorenzo Monaco was operating a prominent workshop, likely situated near the monastery, fulfilling commissions for altarpieces, devotional panels, and illuminated manuscripts for a wide range of patrons.

The Artist-Monk: A Flourishing Workshop and Spiritual Art

Lorenzo Monaco's dual identity as a monk and a highly sought-after professional artist is a fascinating aspect of his career. While monastic artists were not uncommon, Lorenzo's workshop became one of the most important in Florence during the first quarter of the 15th century. His religious devotion undoubtedly informed the intense spirituality and ethereal quality of his paintings. His figures, often elongated and graceful, seem to inhabit a celestial realm, bathed in divine light and rendered with a palette that favored luminous blues, vibrant pinks, and gleaming gold.

His workshop was prolific, producing a significant number of altarpieces for churches and private chapels, smaller panels for personal devotion, and, importantly, exquisite illuminated manuscripts. The Santa Maria degli Angeli scriptorium was famous for its choir books, and Lorenzo Monaco played a leading role in their decoration, creating intricate initials and narrative scenes that are masterpieces of miniature painting. This practice of manuscript illumination, with its emphasis on delicate linearity and rich, jewel-like colors, profoundly influenced his panel paintings.

The International Gothic Style in Lorenzo Monaco's Hands

Lorenzo Monaco is considered the foremost exponent of the International Gothic style in Florence. This style, which flourished across Europe from the late 14th to the mid-15th century, was characterized by its aristocratic elegance, sinuous lines, decorative patterns, and a taste for exotic details and rich materials, especially gold. Figures are typically slender, with flowing draperies that create complex, calligraphic rhythms. While often imbued with a courtly grace, the International Gothic could also convey intense emotion, albeit in a refined and stylized manner.

Monaco's interpretation of this style was uniquely his own. He absorbed influences from Sienese masters like Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi, known for their lyrical lines and graceful figures, and perhaps from earlier Sienese pioneers like Duccio di Buoninsegna. He also built upon the Florentine tradition stemming from Giotto and his followers, such as Taddeo Gaddi and Agnolo Gaddi, but he infused it with a new level of decorative splendor and spiritual intensity. His use of color was particularly innovative, employing vibrant, almost otherworldly hues and subtle modulations of tone to create a sense of divine radiance. The extensive use of gold leaf, not just for backgrounds but also for incised patterns in draperies and halos, further enhanced the precious, otherworldly quality of his work.

Key Artistic Influences Shaping Monaco's Vision

Lorenzo Monaco's artistic development was shaped by a confluence of powerful influences. The legacy of Giotto di Bondone, the great innovator of the early 14th century who brought naturalism and human emotion to Italian painting, was still potent in Florence. Monaco would have been familiar with Giotto's monumental frescoes and panel paintings, and while Monaco's style is less grounded in earthly reality, Giotto's narrative clarity and expressive power left an indelible mark.

More directly, Monaco was influenced by Giotto's followers. Agnolo Gaddi, son of Taddeo Gaddi (himself a prominent pupil of Giotto), was a leading painter in Florence in the late 14th century, and his workshop was known for its large-scale altarpieces and frescoes, characterized by lively narratives and rich color. Spinello Aretino, another contemporary, worked in a vigorous, expressive style that also contributed to the artistic ferment of the period. The Orcagna brothers (Andrea, Nardo, and Jacopo di Cione) also left a significant mark on Florentine art in the mid-14th century with their solemn and hieratic style, which emphasized decorative richness.

Beyond Florence, the Sienese school, with its strong Byzantine heritage and emphasis on linear grace and decorative beauty, played a crucial role. Artists like Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers (Pietro and Ambrogio) had established Siena as a major artistic center, and their influence extended throughout Tuscany. Monaco's elongated figures, flowing lines, and delicate emotionalism owe much to this Sienese tradition.

Masterpieces and Major Commissions: A Legacy in Gold and Color

Lorenzo Monaco's oeuvre is rich with masterpieces that exemplify his unique artistic vision. Among his most celebrated works is the _Coronation of the Virgin_, painted in 1414 for the high altar of his own monastery, Santa Maria degli Angeli, and now housed in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. This large-scale altarpiece is a dazzling symphony of color and light, depicting Christ crowning the Virgin Mary amidst a celestial choir of saints and angels. The figures are elongated and ethereal, their draperies swirling in elegant, calligraphic patterns. The extensive use of gold, the vibrant blues of the Virgin's robe, and the rainbow hues of the seraphim create an atmosphere of transcendent glory. This work is often considered the apogee of the International Gothic style in Florence.

Another significant commission was the _Monte Oliveto Altarpiece_, completed around 1407-1410 for the Olivetan monastery of San Bartolomeo a Monte Oliveto, near Florence, and now in the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence. This polyptych features a central panel of the Virgin and Child enthroned, flanked by saints. The work showcases Monaco's mastery of graceful figural representation and his ability to convey tender emotion, particularly in the interaction between the Virgin and Child.

Numerous _Madonna and Child_ panels by Lorenzo Monaco survive, attesting to the popularity of this theme for private devotion. One notable example, dated around 1413, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. It displays his characteristic use of delicate lavender and translucent white for the Virgin's robes, emphasizing her humility and purity, set against a traditional gold ground. The tender, introspective mood is typical of Monaco's devotional works.

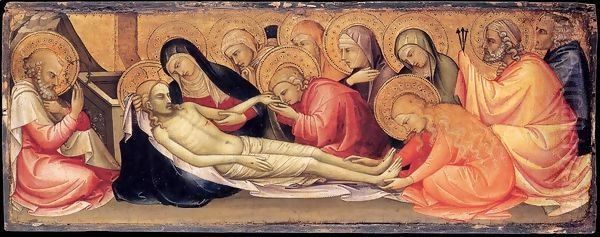

The _Lamentation over the Dead Christ_ (also known as the Pietà), dated 1404 and now in the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, demonstrates Monaco's capacity for conveying profound grief, albeit with his customary elegance. The elongated body of Christ is supported by the Virgin, St. John, and Mary Magdalene, their sorrow expressed through graceful gestures and sorrowful expressions.

His work as a manuscript illuminator was equally important. He decorated numerous choir books for Santa Maria degli Angeli and other institutions. These illuminations, often featuring historiated initials (large letters containing narrative scenes), are characterized by their vibrant colors, intricate details, and lively compositions. Examples can be found in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence.

Other notable works include an _Adoration of the Magi_ (Uffizi Gallery, c. 1420-22), which captures the pageantry and exoticism inherent in the theme, rendered with his typical flowing lines and rich colors. _The Martyrdom of Pope Caius_ (c. 1394-1395, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) is an earlier work, part of a predella, showing his developing style and ability to handle dramatic narrative. A panel depicting _King David_ (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) showcases his skill in rendering regal figures with expressive intensity. His _Christ in the Garden of Olives_ also highlights his ability to convey deep spiritual and emotional states.

A Confluence of Styles: Tradition and the Dawn of the Renaissance

Lorenzo Monaco worked during a period of profound artistic change in Florence. While he was perfecting his International Gothic style, a new artistic language – the Early Renaissance – was beginning to emerge. Artists like Filippo Brunelleschi, the architect and inventor of linear perspective, Donatello, the sculptor who revived classical naturalism, and Masaccio, the painter who revolutionized fresco and panel painting with his use of perspective, chiaroscuro, and psychologically compelling figures, were ushering in a new era.

Interestingly, Lorenzo Monaco, despite being a contemporary of these innovators, largely remained committed to the Gothic aesthetic. He did not fully embrace the new principles of scientific perspective or the robust, classicizing naturalism that characterized the work of Masaccio or Donatello. His figures retained their elongated proportions and graceful, otherworldly quality. His space remained more symbolic and decorative than illusionistically deep. This "rejection" of Renaissance innovations should not be seen as a failing, but rather as a testament to the enduring power and appeal of the International Gothic style, of which he was a supreme master. His art offered a different kind of beauty, one rooted in spiritual transcendence, lyrical elegance, and decorative splendor.

His workshop, however, was not entirely isolated from these new currents. Some later works show a slightly greater sense of volume and a more restrained emotionalism, perhaps reflecting a subtle awareness of the changing artistic climate. Nevertheless, his primary allegiance remained with the sophisticated and spiritualized world of the International Gothic.

Contemporaries and the Florentine Milieu

The Florence of Lorenzo Monaco's time was a vibrant artistic center. Besides the aforementioned pioneers of the Renaissance – Masaccio, Brunelleschi, Donatello, and the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti (famous for the Baptistery doors) – there were other notable artists working in related or contrasting styles. Gentile da Fabriano, another master of the International Gothic style, worked in Florence for a period (1420-1425) and produced his masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi (1423, Uffizi), which shares with Monaco's work a love for intricate detail, rich color, and courtly elegance.

The presence of these diverse artistic personalities created a dynamic environment. While Masaccio was painting the groundbreaking Brancacci Chapel frescoes with their revolutionary naturalism, Lorenzo Monaco was producing altarpieces that spoke to a different, but equally valid, set of aesthetic and spiritual values. His art appealed to patrons who appreciated the traditional religious imagery infused with a heightened sense of grace and divine splendor. Artists like Fra Giovanni da Fiesole, better known as Fra Angelico, who was younger than Monaco and also a monk (Dominican), would later bridge the gap, combining Monaco's spiritual luminosity and radiant color with the new Renaissance understanding of form and space.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Lorenzo Monaco continued to be highly productive throughout the first two decades of the 15th century. His workshop was a major force in Florentine art, training assistants and disseminating his influential style. He received numerous important commissions and his reputation extended beyond Florence.

The exact date of Lorenzo Monaco's death is uncertain, but it is generally placed around 1425. Some sources suggest he may have suffered from an illness, possibly an infection or tumor, but details are scarce. He was likely buried in his monastery, Santa Maria degli Angeli, the spiritual and artistic home that had shaped so much of his life and work.

Lorenzo Monaco's legacy was significant. He was the last great painter of the purely Gothic tradition in Florence, but his influence extended into the Early Renaissance. His most important artistic heir was Fra Angelico, who, as mentioned, absorbed Monaco's spiritual intensity, his luminous color palette, and his delicate linearity, adapting these qualities to the new Renaissance aesthetic. Other, more minor painters also show his influence, continuing his style well into the 15th century.

His work represents a vital link between the art of the 14th century (the Trecento) and the full flowering of the Renaissance in the 15th century (the Quattrocento). He demonstrated the enduring vitality of the Gothic tradition while also, in his own way, contributing to the evolving artistic language of his time through his sophisticated compositions and expressive use of color.

Anecdotes and Scholarly Debates

While detailed biographical information about Lorenzo Monaco is somewhat limited, as is common for artists of this period, certain aspects of his life and work continue to generate scholarly discussion.

His dual identity as a monk and the head of a major commercial workshop is, in itself, noteworthy. It highlights the complex relationship between religious life and artistic production in this era.

The precise nature and extent of his training remain debated. Whether he was primarily trained within the Santa Maria degli Angeli scriptorium or had prior workshop experience before joining the order is not definitively known. His stylistic evolution, from earlier works that show stronger affinities with late Giottesque painting to his mature International Gothic style, is a subject of ongoing art historical analysis.

His conscious decision not to adopt the revolutionary perspectival systems and naturalistic figural style of Masaccio and Brunelleschi is often commented upon. This "conservatism" is interpreted by some as a limitation, but by others as a deliberate artistic choice, reflecting a different set of aesthetic priorities focused on spiritual expression and decorative harmony.

Certain iconographic details in his paintings, such as the somewhat perplexing depiction of the beheaded Pope Caius still standing in The Martyrdom of Pope Caius, can spark debate about their intended meaning and sources.

Lorenzo Monaco in Museum Collections and Exhibitions

Today, Lorenzo Monaco's works are prized possessions of major museums around the world. The largest and most important collections are, naturally, in Florence, particularly in the Uffizi Gallery and the Galleria dell'Accademia. The Uffizi holds his monumental Coronation of the Virgin and the Adoration of the Magi, among others. The Accademia houses the Monte Oliveto Altarpiece and the Lamentation over the Dead Christ.

Outside Italy, significant works can be found in the National Gallery, London (e.g., panels from the San Benedetto Altarpiece); the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (e.g., Madonna and Child, King David, and several predella panels); the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (The Martyrdom of Pope Caius); the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; and many other prestigious institutions in Europe and North America.

His importance has been recognized in major exhibitions. A landmark monographic exhibition, "Lorenzo Monaco: A Bridge from Giotto's Heritage to the Renaissance" (Lorenzo Monaco: Dalla tradizione giottesca al Rinascimento), was held at the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence in 2006. This exhibition brought together many of his key works, allowing for a comprehensive reassessment of his artistic achievement and his place in the transition from Gothic to Renaissance art. His paintings are also frequently included in broader surveys of Florentine painting and the International Gothic style.

Historical Assessment and Enduring Significance

Lorenzo Monaco holds a secure and esteemed place in the history of Italian art. He is recognized as the leading Florentine painter of the International Gothic style, an artist who brought this elegant and courtly manner to its highest point of refinement and spiritual intensity in the city. His mastery of line, his radiant and often unconventional color harmonies, and his ability to convey profound religious feeling mark him as an artist of exceptional talent.

While he did not embrace the revolutionary changes that heralded the High Renaissance, his work was not an anachronism. Rather, it represented the glorious culmination of a long and rich artistic tradition. He provided a vital continuity with the art of the 14th century, even as Florence was on the cusp of a new artistic era. His influence, particularly on Fra Angelico, ensured that the spiritual luminosity and graceful lyricism of his art would be carried forward and integrated into the new Renaissance vocabulary.

Lorenzo Monaco's paintings continue to captivate viewers with their ethereal beauty, their exquisite craftsmanship, and their deep sense of devotion. They offer a window into a world where the sacred and the beautiful were inextricably intertwined, and where art served as a powerful conduit for spiritual experience. As an artist-monk, he embodied this fusion, creating works that are both aesthetically stunning and profoundly moving, securing his legacy as a master of the luminous and the divine.