Angelica Kauffmann stands as one of the most celebrated and successful artists of the 18th century, a remarkable achievement for a woman in an era dominated by male practitioners. A Swiss-born painter who achieved international fame, she navigated the complex artistic and social landscapes of Italy and England with exceptional skill and talent. A founding member of London's Royal Academy of Arts, Kauffmann specialized in history painting, portraiture, and decorative schemes, becoming a key figure in the Neoclassical movement, albeit one infused with a distinct grace and sensibility that captivated patrons across Europe, from London royalty to the Russian Tsarina.

An Alpine Prodigy: Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Maria Anna Angelika Katharina Kauffmann was born in Chur, in the Grisons region of Switzerland, on October 30, 1741. Her artistic inclinations were nurtured from an exceptionally young age, largely thanks to her family environment. Her father, Johann Joseph Kauffmann, was a skilled, albeit relatively modest, painter primarily working on murals and portraits for local churches and patrons. He recognized his daughter's prodigious talent early on and became her first and most influential teacher, guiding her in drawing and painting techniques.

Her mother, Cleophea Lutz, was an educated woman who reportedly instilled in Angelica a love for languages and music. Young Angelica quickly became fluent in German, Italian, French, and later English, skills that would prove invaluable in her international career. She also showed considerable musical talent, particularly as a singer, leading to a period of youthful indecision about whether to pursue a career in music or painting – a dilemma she later famously depicted in one of her allegorical self-portraits.

By the age of twelve, Angelica was already a recognized talent, assisting her father with commissions and even receiving independent portrait requests. An early self-portrait from this time reveals a startling maturity and technical proficiency. Her father understood that provincial Switzerland and Austria offered limited scope for her burgeoning abilities, and much of her adolescence was spent travelling with him through Austria and Italy, seeking commissions and, crucially, opportunities for artistic education.

The Italian Crucible: Education and Early Success

Italy was the essential destination for any aspiring artist in the 18th century, the repository of Classical antiquity and Renaissance masterpieces. Angelica and her father spent several formative years travelling the peninsula. They visited Milan, Bologna, Florence, Naples, and Venice, but it was Rome that proved most decisive for her development. There, she immersed herself in the study of ancient sculpture and the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters like Raphael and Carracci. She honed her skills by copying Old Masters, a standard practice for artistic training.

In Italy, Kauffmann's talent, charm, and linguistic abilities quickly gained her entry into artistic and intellectual circles. She befriended key figures who would shape her career and outlook. Among the most significant was the German archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, a leading theorist of Neoclassicism. Winckelmann admired Kauffmann's talent and character, and his ideals of "noble simplicity and calm grandeur" derived from Greek art profoundly influenced her developing style. She painted a sensitive portrait of Winckelmann in 1764, capturing his intellectual intensity.

Her growing reputation was solidified by her election to prestigious artistic academies. In 1762 she was made a member of the Accademia Clementina in Bologna, and in 1765, she was welcomed into Rome's Accademia di San Luca, a significant honour for a young female artist. She also associated with other foreign artists working in Rome, including the American painter Benjamin West, who would later play a role in her London career, and the German Neoclassicist Anton Raphael Mengs, whose refined style and use of colour also left an impression on her work. These Italian years were crucial, equipping her with technical skill, theoretical knowledge, and important connections.

London Calling: Fame and the Royal Academy

In 1766, encouraged by Lady Wentworth, the wife of the British ambassador in Venice whom she had met and painted, Angelica Kauffmann arrived in London. England was experiencing a surge in artistic activity and patronage, and Kauffmann's arrival was perfectly timed. Her reputation preceded her, and she quickly became a sensation in London society. Her talent, combined with her cultivated manners, musical accomplishments, and fluency in English, made her a popular figure in elite circles.

She established a successful studio, attracting a stream of commissions for portraits from the aristocracy and fashionable society. Her portraits were admired for their elegance, flattering likenesses, and often incorporated subtle mythological or allegorical allusions that appealed to the Neoclassical taste of the era. She painted prominent figures like the actor David Garrick and members of the royal family.

Her closest artistic friendship in London was with Sir Joshua Reynolds, the preeminent portrait painter of the day and the future first president of the Royal Academy. Reynolds recognized her talent, promoted her work, and they frequently dined and socialized together. Their closeness inevitably sparked gossip and speculation, fueled further by satirical prints, but their professional respect appears genuine. Reynolds's own style, influenced by the Grand Manner, likely reinforced Kauffmann's ambitions in history painting.

A Founding Mother: The Royal Academy of Arts

Kauffmann's rapid ascent culminated in a singular honour. In 1768, when the Royal Academy of Arts was founded under the patronage of King George III, Angelica Kauffmann was named among the 36 founding members. She and the flower painter Mary Moser were the only two women included in this prestigious group, a testament to their exceptional standing in the London art world. This was a landmark achievement, granting women official recognition within the highest echelon of the British artistic establishment, although their participation in Academy governance and life drawing classes remained restricted.

Kauffmann actively participated in the Academy's annual exhibitions for many years, primarily submitting history paintings based on classical literature, mythology, and British history. These ambitious works helped solidify her reputation not just as a portraitist but as a serious exponent of the most highly regarded genre of painting. Her contributions were generally well-received, further enhancing her fame both in Britain and on the Continent. Other founding members included prominent figures like Benjamin West, Thomas Gainsborough (though his relationship with the RA was complex), and Francesco Bartolozzi, an Italian engraver who would reproduce many of Kauffmann's designs.

Artistic Signature: Neoclassicism with Grace

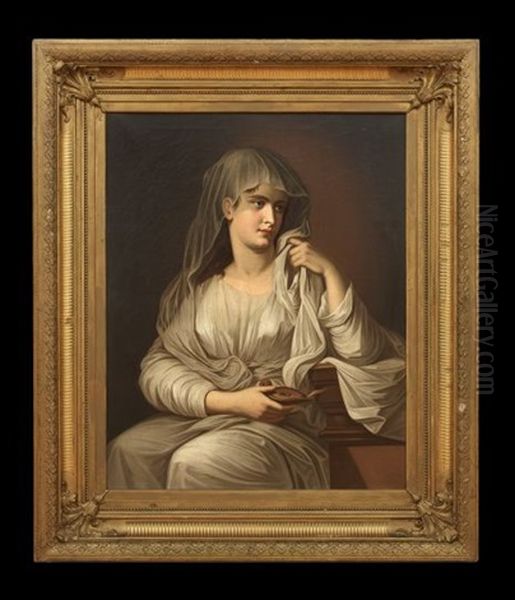

Angelica Kauffmann's style is firmly rooted in Neoclassicism, embracing its emphasis on clarity of form, linear precision, idealized figures, and themes drawn from classical history and mythology. However, her interpretation of Neoclassicism was distinct from the more austere or heroic modes developing in France under artists like Jacques-Louis David. Kauffmann tempered classical severity with a Rococo-derived grace, elegance, and sentiment. Her figures often possess a gentle charm and emotional sensitivity, rendered with fluid lines and a soft, harmonious palette.

While portraiture provided a steady income, Kauffmann's true ambition lay in history painting. She tackled subjects from Homer, Virgil, and Plutarch, as well as scenes from British history, often focusing on moments of pathos, virtue, or feminine heroism. Works like Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, Pointing to Her Children as Her Treasures exemplify her interest in didactic, morally uplifting themes centered on female figures. Her approach often highlighted emotional relationships and virtuous conduct rather than grand political or military drama.

Her colour palette, likely influenced by her studies in Venice and the work of Mengs, tended towards lighter, clearer tones compared to the darker chiaroscuro of earlier Baroque painting. Her compositions are typically balanced and harmonious, often featuring elegantly posed figures arranged in frieze-like arrangements reminiscent of classical reliefs. This blend of Neoclassical structure and Rococo sensibility gave her work a wide appeal, perceived as both intellectually respectable and aesthetically pleasing.

Masterpieces and Illustrious Patrons

Throughout her prolific career, Kauffmann produced an extensive body of work, estimated at over 500 paintings, alongside numerous drawings and designs for decorative arts. Several works stand out as particularly representative of her achievements. Her Self-Portrait Hesitating Between the Arts of Music and Painting (c. 1791) is a compelling allegorical exploration of her own life choices, depicting herself caught between the personifications of Painting and Music. It showcases her skill in self-representation and allegorical invention.

Her history paintings were highly regarded. Virgil Reading the Aeneid to Augustus and Octavia (1788) demonstrates her ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and convey subtle emotional narratives. Cleopatra Adorning the Tomb of Mark Antony (c. 1769-70) is a poignant example of her focus on female figures from history, rendered with characteristic sensitivity. Mythological subjects like Rinaldo and Armida or Telemachus and the Nymphs of Calypso allowed her to explore themes of love and enchantment within elegant, idealized settings.

Kauffmann's portraits remained highly sought after. Besides individual portraits like those of the Duchess of Courland or Louisa Hammond, she excelled at group portraits and conversation pieces. Her patrons included the highest echelons of European society. In Britain, she received commissions from King George III and Queen Charlotte for decorations at Buckingham House and Frogmore House. Abroad, her clients included Emperor Joseph II of Austria, Catherine the Great of Russia, and King Stanisław August Poniatowski of Poland. Her fame was further amplified by the numerous engravings made after her paintings by artists like Francesco Bartolozzi and William Wynne Ryland, disseminating her compositions widely.

Life's Tapestry: Marriage, Society, and Scandal

Despite her professional success, Kauffmann's personal life was marked by a significant early upheaval. In 1767, she was deceived into marrying a man calling himself Count Frederick de Horn, who soon proved to be an imposter, adventurer, and bigamist. The marriage was a disaster, causing considerable scandal and personal distress. With the support of her father and influential friends, she managed to secure a declaration of nullity the following year, but the episode left her wary and perhaps contributed to the gossip that sometimes surrounded her.

For many years, she remained single, focusing on her career. In 1781, however, she married the Italian painter Antonio Zucchi. Zucchi, originally from Venice, was a decorative painter who had also worked in England, notably collaborating with the architect Robert Adam. Their marriage appears to have been a stable and supportive partnership. Zucchi, fifteen years her senior, largely gave up his own painting career to manage Angelica's business affairs and assist with the practical aspects of her thriving studio. His knowledge of decorative painting may also have influenced her work in that field.

Throughout her time in London and later in Rome, Kauffmann maintained an active social life. She was known for her intelligence and charm, hosting gatherings that attracted artists, writers, musicians, and members of the aristocracy. She associated with the Bluestockings, an informal network of educated, intellectual women in London, including figures like Elizabeth Montagu and Hannah More, who promoted female learning and conversation. This engagement with intellectual circles further enhanced her status and reputation.

Circles of Influence: Friends and Contemporaries

Kauffmann's career was interwoven with relationships with many of the leading artistic and intellectual figures of her time. Her friendship with Sir Joshua Reynolds in London was pivotal, providing support and access within the British art establishment, despite the accompanying rumors. The early guidance and Neoclassical ideals imparted by Johann Joachim Winckelmann in Rome laid crucial theoretical foundations for her art.

Her friendship with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was particularly significant during her later years in Rome. The great German writer visited Rome during his Italian Journey (1786-1788) and became a close friend and admirer of Kauffmann. He frequented her studio, discussed art with her, and praised her talent and sensibility effusively in his writings, famously describing her as having an "unbelievable and, truly, immense talent." She, in turn, drew illustrations for his play Egmont and painted his portrait. This association with Goethe further cemented her reputation in German-speaking Europe.

Her husband, Antonio Zucchi, provided essential personal and professional support in the later part of her career. The engravers Francesco Bartolozzi and William Wynne Ryland played a key role in popularizing her work through prints. She also interacted with numerous other artists, including Benjamin West, Nathaniel Dance-Holland (another London portraitist linked to her by gossip), and later in Rome, the leading Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova, who deeply respected her.

Navigating Fame and Controversy

As a highly visible and successful woman in the public eye, Angelica Kauffmann inevitably faced scrutiny and challenges. The scandal of her brief first marriage to the imposter Count de Horn was a significant source of gossip and potential damage to her reputation, which she skillfully managed to overcome. The persistent rumors linking her romantically with male colleagues like Reynolds and Dance-Holland were another burden, reflecting societal discomfort with independent, successful women.

This discomfort sometimes manifested in professional contexts. In 1775, the Irish painter Nathaniel Hone submitted a satirical painting titled The Conjuror to the Royal Academy exhibition. It was widely interpreted as mocking Reynolds's reliance on Old Masters and allegedly included a derogatory caricature of Kauffmann (possibly nude), perhaps playing on the rumors about their relationship. Kauffmann protested vehemently, and the offending figures were painted out before the exhibition opened, but the incident highlighted the undercurrents of jealousy and sexism she sometimes encountered.

Furthermore, while her elegant and sentimental style was widely popular, it also drew criticism from some quarters for lacking the perceived "masculine" vigour and seriousness expected of high art, particularly history painting. Some later critics dismissed her work as overly pretty or decorative. Nevertheless, Kauffmann navigated these challenges with remarkable resilience, leveraging her talent, diplomatic skills, and powerful network of patrons and friends to maintain her preeminent position.

Roman Twilight: The Final Chapter

In 1781, shortly after her marriage to Antonio Zucchi, Angelica Kauffmann decided to leave London and return to Rome. The move was prompted partly by her father's declining health (he died in Venice en route) and perhaps a desire to return to the city that had been so formative for her art. Zucchi accompanied her, and they established a home and studio near the Spanish Steps.

Her Roman years were far from a retirement. Her international fame ensured a steady stream of visitors and commissions. Her studio became a prominent cultural hub, a must-see destination for artists, writers, collectors, and Grand Tourists visiting the Eternal City. She continued to paint prolifically, producing portraits, history paintings, and religious subjects. She maintained her connections with European royalty and aristocracy, fulfilling commissions sent from abroad.

Antonio Zucchi died in 1795, leaving Angelica a wealthy widow. She continued to work, though perhaps at a slower pace, and remained a revered figure in Rome's artistic community. She enjoyed a close friendship with the sculptor Antonio Canova, the leading light of Roman Neoclassicism in this later period. When Angelica Kauffmann died in Rome on November 5, 1807, at the age of 66, Canova himself organized her lavish funeral. In a mark of the immense respect she commanded, her funeral procession was modeled on that held for the Renaissance master Raphael, with two of her paintings carried alongside her bier to her final resting place in the church of Sant'Andrea delle Fratte.

Enduring Legacy: Reappraisal of a Pioneer

Angelica Kauffmann's impact was considerable during her lifetime. She was a true international celebrity, one of the most famous artists of her era, male or female. As a highly successful female history painter and a founding member of the Royal Academy, she broke significant barriers and served as an inspiration for subsequent generations of women artists, such as Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun in France. Her refined and accessible version of Neoclassicism significantly shaped contemporary taste, not only in painting but also in the decorative arts, influencing interior design (like the work of Robert Adam, who incorporated her painted panels), furniture, and porcelain decoration (e.g., Wedgwood).

However, her reputation declined significantly during the 19th century. Changing artistic tastes, which favoured Romanticism and later Realism, found her Neoclassical sentimentality less appealing. Art history, largely written by men, tended to marginalize female artists, often dismissing her work with faint praise or focusing on the anecdotal aspects of her life.

It was not until the later 20th century, with the rise of feminist art history, that Angelica Kauffmann's work and career underwent a serious critical reappraisal. Scholars began to re-examine her achievements, recognizing the skill and intelligence behind her art, the ambition of her history paintings, and the significance of her success in overcoming the limitations placed on women artists. Today, she is acknowledged as a major figure of European Neoclassicism, a pioneering female professional, and an artist whose work offers fascinating insights into the culture, patronage, and gender dynamics of the 18th century. Her paintings are held in major museums worldwide, ensuring her legacy endures.

Conclusion: An Artist of Talent and Tenacity

Angelica Kauffmann's life and career remain extraordinary. Emerging from a relatively modest background, she rose through talent, hard work, intelligence, and social acumen to become one of the most sought-after and highly paid artists in Europe. She successfully navigated the male-dominated art worlds of Rome and London, achieving recognition in the most prestigious genres and institutions. Her unique blend of Neoclassical principles with Rococo grace created a style that resonated deeply with the sensibilities of her time, while her role as a founding member of the Royal Academy marked a crucial step forward for women in the arts. More than just a painter of charming canvases, Kauffmann was a shrewd businesswoman, a cultivated member of society, and a trailblazer whose influence extended far beyond her studio, leaving an indelible mark on the art and culture of the late 18th century.