Daniele Crespi (c. 1598–1630) stands as a significant, albeit tragically short-lived, figure in the landscape of Italian Baroque painting. Born in Busto Arsizio, near Milan, Crespi emerged as one of the leading artists of the Lombard school during the early 17th century. His career, though spanning little more than a decade, was marked by a decisive move away from the lingering complexities of Mannerism towards a more direct, emotionally resonant, and compositionally clear form of Baroque expression. His work embodies the religious fervor and artistic ideals of the Counter-Reformation, particularly as promoted in Milan, leaving a distinct imprint on the art of Northern Italy before his untimely death in the devastating plague of 1630.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Daniele Crespi's artistic journey began in Lombardy, a region rich with artistic traditions, notably influenced by the legacy of Leonardo da Vinci and the subsequent development of a distinct regional style. While details of his earliest training are somewhat sparse, sources suggest he may have initially studied with the late Mannerist painter Guglielmo Caccia, known as Il Moncalvo. Moncalvo, active primarily in Piedmont and Lombardy, represented the established style that Crespi would soon react against.

His most formative training, however, came under the guidance of Giovanni Battista Crespi, known as Il Cerano (c. 1573–1632). Il Cerano was a towering figure in Milanese art, alongside Giulio Cesare Procaccini and Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli (Il Morazzone). He was a painter, sculptor, and architect deeply involved in the artistic projects spurred by the Counter-Reformation, particularly under the patronage of Cardinal Federico Borromeo. Although Daniele Crespi shared a surname with his master, they were not related. Studying with Il Cerano provided Daniele with a strong foundation in Milanese artistic practices, characterized by intense emotion, dramatic lighting, and often complex compositions, though Cerano himself was moving towards a greater clarity in his later years.

Breaking from Mannerism: The Emergence of a New Style

Daniele Crespi is often celebrated as one of the first Milanese painters of his generation to decisively break free from the prevailing Mannerist tendencies, which had sometimes manifested in Lombardy as an overly stylized, intricate, and emotionally artificial approach. Crespi sought a greater naturalism, a clarity of narrative, and a more profound and direct emotional impact in his work. His style is characterized by its formal and compositional simplicity compared to the elaborate works of some predecessors and contemporaries.

His figures possess a tangible solidity and psychological presence. He focused on conveying the core emotional and spiritual message of his subjects, often religious narratives, with an immediacy that resonated with the Counter-Reformation's call for art that could instruct and move the faithful. This clarity and directness did not preclude drama; rather, Crespi achieved dramatic effect through focused compositions, strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and the expressive rendering of human emotion.

Influences: Cerano, Caravaggio, and the Lombard Tradition

While Il Cerano was a crucial early influence, Daniele Crespi quickly developed his own distinct artistic personality. He absorbed lessons from his master regarding emotional intensity and painterly technique but steered towards greater realism and compositional restraint. His work shows an awareness of the revolutionary naturalism of Caravaggio, whose influence was spreading throughout Italy. Crespi adopted Caravaggio's dramatic use of light and shadow to heighten the emotional tension and focus the viewer's attention, though generally without Caravaggio's stark, often brutal, realism.

Crespi's style also remained rooted in the Lombard tradition, which valued realism, careful observation of detail, and a certain emotional tenderness, traceable back to Leonardo da Vinci's Milanese period. The psychological depth in Crespi's figures, particularly in their facial expressions and gestures, echoes Leonardo's interest in capturing the "motions of the mind." Furthermore, some scholars detect influences from the Venetian school, perhaps in his handling of color and light, possibly absorbed through prints or contact with Venetian-influenced artists active in Lombardy. Artists like Titian and Giorgione had set precedents for atmospheric effects and rich color palettes that subtly informed Northern Italian painting.

Major Works and Religious Themes

Daniele Crespi's oeuvre is dominated by religious subjects, reflecting the intense spiritual climate of Milan under the guidance of figures like Saint Charles Borromeo and his nephew, Cardinal Federico Borromeo. These patrons actively promoted art that was theologically sound, emotionally engaging, and clear in its message. Crespi excelled in meeting these demands.

One of his most celebrated works is the Supper of St. Charles Borromeo, painted for the church of Santa Maria della Passione in Milan. This painting exemplifies his mature style: a simple, austere setting focuses attention on the saint's pious act of fasting. The composition is clear, the figures are rendered with sober realism, and the emotional tone is one of quiet devotion and humility, perfectly embodying the Counter-Reformation ideals championed by Borromeo himself.

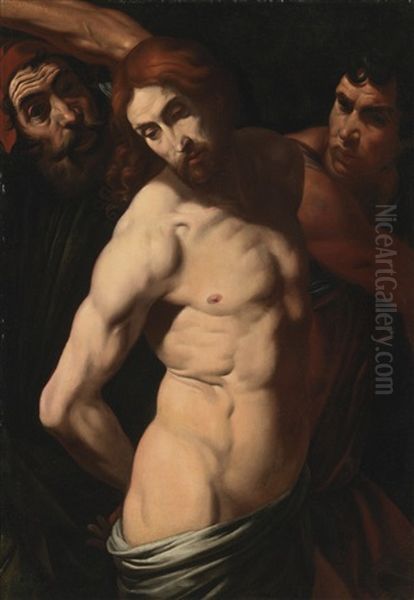

Another powerful work is The Mocking of Christ (c. 1621-22). Here, Crespi demonstrates his ability to convey intense suffering and dignity simultaneously. The dramatic lighting highlights Christ's face and torso, emphasizing his vulnerability, while the surrounding figures are depicted with a convincing, almost brutal, energy. The painting balances physical realism with profound spiritual content.

Crespi was also a highly accomplished fresco painter. His most extensive project was the decoration of the Certosa di Garegnano, a Carthusian monastery near Milan, undertaken in the late 1620s. Here, he painted scenes from the life of Saint Bruno, the founder of the Carthusian order, as well as other religious subjects. These frescoes showcase his skill in handling large-scale compositions, integrating figures within architectural spaces, and maintaining narrative clarity and emotional depth even in complex cycles. His use of light and color in these frescoes, including symbolic uses of blues and purples, demonstrates his technical mastery. Works like the Resurrection scene within the Certosa cycle highlight his dynamic approach to composition and figure portrayal.

Other notable works include the Crucifixion, The Penitence of St. Joseph (reflecting early influences from Procaccini and Cerano), and The Last Supper painted for the church of San Benedetto in Brieglia, which shows his engagement with classical compositional models, likely Leonardo's famous version, reinterpreted through his own Baroque sensibility. He also produced portraits, although fewer survive. A portrait attributed to him, possibly depicting Antonio Olgiati, suggests a stylistic connection or awareness of contemporary Lombard portraitists.

Contemporaries and the Milanese Artistic Milieu

Daniele Crespi worked within a vibrant artistic environment in Milan. His primary point of reference was his teacher, Il Cerano, but he was also contemporary with the other two leading figures of the Milanese school: Giulio Cesare Procaccini (1574–1625) and Il Morazzone (Pier Francesco Mazzucchelli, 1573–1626). While Procaccini often displayed a more elegant, Parmigianino-influenced style, and Morazzone was known for his dynamic energy and sometimes visionary intensity, Crespi carved out his niche with his emphasis on clarity, realism, and restrained emotional power.

He likely interacted with other Lombard artists as well. His work on the Supper of St. Charles Borromeo places him in the context of artists decorating Milanese churches dedicated to the saint. Connections with Tanzio da Varallo (Antonio d'Enrico, c. 1575/80–c. 1632/33), another powerful Lombard realist painter active in Varallo and Milan, are plausible, given their shared interest in dramatic naturalism, possibly stemming from Caravaggesque influence filtered through Lombard sensibilities. The comparison of his portraiture style to that of Antonio Olgiati further suggests his embeddedness within the local network of artists.

The overarching influence on the artistic production of this era was the patronage and direction provided by Cardinal Federico Borromeo, founder of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana and Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. Borromeo's treatise De pictura sacra (On Sacred Painting) outlined the principles that should guide religious art, emphasizing decorum, clarity, historical accuracy, and emotional piety – principles clearly reflected in Crespi's major commissions.

Legacy and Influence: Students and Followers

Despite his tragically short career, Daniele Crespi's impact was significant, particularly within Lombardy. His move towards a clearer, more emotionally direct Baroque style influenced subsequent developments in the region. He bridged the gap between the complex Mannerism of the late 16th century and the more fully developed Baroque of the mid-17th century in Milan.

Crespi also trained a number of pupils, ensuring the continuation of his artistic approach, albeit adapted by each individual. Among his most notable students were Agostino Castellacci and Francesco Manicini, who reportedly gained considerable fame in Rome, suggesting they carried elements of Crespi's Lombard style to the center of the Italian art world.

Other documented or attributed pupils include Federico Bencovich (though his primary training is often linked elsewhere, some sources connect him to Crespi, and he later worked in Venice and Central Europe), Girolamo Donnini, Antonio Santi, Innocenza Monti, and Giuseppe Maria Bartolotti. The fact that some of these artists found success outside Italy, in places like Germany and Poland, indicates the potential reach of Crespi's influence, transmitted through his workshop. His legacy lies in his contribution to the distinctive character of Lombard Baroque painting, marked by its blend of realism, emotional intensity, and compositional clarity.

A Career Cut Short

The promising trajectory of Daniele Crespi's career came to an abrupt and tragic end during the great Italian plague of 1629–1631, which ravaged Northern Italy, particularly Milan (famously described in Alessandro Manzoni's novel The Betrothed). In 1630, Daniele Crespi, along with his wife and children, succumbed to the epidemic. He was only around 32 years old.

His death silenced one of the most talented and forward-looking voices in Milanese painting at a moment when his style had reached full maturity. It is left to speculation how his art might have further evolved had he lived longer. Nevertheless, the body of work he produced in just over a decade secured his place as a key figure of the early Baroque in Lombardy. His paintings continue to be admired for their technical skill, their profound emotional resonance, and their clear articulation of the spiritual ideals of his time. His works are held in major collections, including the Pinacoteca di Brera and the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, and the Prado Museum in Madrid, testifying to his enduring importance. Daniele Crespi remains a testament to the potent combination of regional tradition and innovative spirit that characterized Italian Baroque art.