Gustave Moreau stands as a singular figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. A painter whose work defies easy categorization, he navigated the currents of Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and the burgeoning avant-garde, ultimately forging a path that established him as a crucial precursor and leading exponent of the Symbolist movement. His canvases, rich with mythological, biblical, and literary allusions, are not mere illustrations but complex visual poems exploring the depths of the human psyche, the mysteries of life and death, and the power of the unseen. Moreau's unique vision, characterized by opulent detail, jewel-like color, and an often unsettling ambiguity, captivated his contemporaries and left an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists.

Early Life and Formative Years

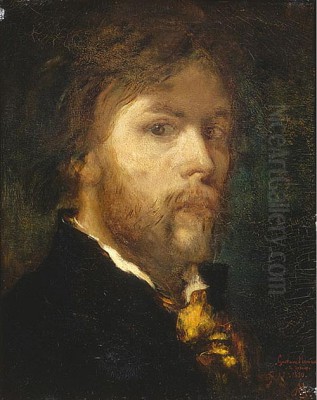

Gustave Moreau was born in Paris on April 6, 1826, into a cultured and affluent bourgeois family. His father, Louis Jean Marie Moreau, was a respected architect for the city of Paris, providing a stable and supportive environment. His mother, Adèle Pauline des Moutiers, was a talented musician, contributing to a home atmosphere where the arts were appreciated. This upbringing undoubtedly fostered Moreau's innate artistic inclinations, which became apparent from an early age.

Moreau's formal education was somewhat irregular, partly due to his delicate health as a child. He attended the Collège Rollin in Paris for his secondary education between approximately 1836 and 1840. However, he did not complete his studies in the traditional manner. The premature death of his older sister, Camille, in 1840 deeply affected the family and led Moreau to leave the college. He returned home, where his devoted father took charge of his education, preparing him privately for the baccalaureate examination, which he successfully passed. This period of home study likely allowed him the freedom to pursue his growing passion for drawing and painting.

His family recognized and encouraged his artistic talent. An early sign of his future direction came in 1841 when, at the age of fifteen, Moreau undertook his first journey to Northern Italy. This trip, though brief, was profoundly influential. He returned with a sketchbook filled with drawings, indicating a burgeoning fascination with the art of the past. This experience ignited an enduring interest in the artistic traditions of Classical Antiquity, the Byzantine era, and particularly the masters of the early Italian Renaissance, whose work would continue to inform his own throughout his career.

The Path to Art: Education and Early Influences

Driven by his artistic ambitions, Moreau sought formal training. In 1846, he gained admission to the prestigious École Royale des Beaux-Arts (Royal Academy of Fine Arts) in Paris, the bastion of academic art education in France. There, he entered the studio of François-Édouard Picot, a painter respected for his historical and portrait subjects executed in a Neoclassical style. Picot provided Moreau with a solid grounding in academic principles, emphasizing draftsmanship, composition, and the study of classical forms.

However, Moreau's artistic temperament resonated more deeply with the spirit of Romanticism and its burgeoning offshoots. He soon formed a close relationship with Théodore Chassériau, a brilliant artist who had himself been a student of the Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres but had developed a distinctive style blending classical linearity with the color and exoticism of Romanticism, particularly influenced by Eugène Delacroix. Chassériau became a significant mentor and friend to Moreau, encouraging his exploration of richer color palettes, more expressive themes, and subjects drawn from literature and myth. Chassériau's tragic early death in 1856 was a profound loss for Moreau.

Despite his talent and dedication, Moreau faced setbacks in the highly competitive academic system. He attempted twice, in 1848 and 1849, to win the coveted Prix de Rome, a scholarship allowing winners to study at the French Academy in Rome. His failure to secure this prestigious award was a disappointment but ultimately may have liberated him from the stricter constraints of the official academic path. Instead of Rome, Moreau turned to the Louvre Museum as his classroom, diligently copying the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters like Rembrandt, Titian, and Veronese. This practice allowed him to absorb diverse techniques and deepen his understanding of composition and color, gradually shaping his own independent artistic voice.

Forging a Unique Vision: Italy and Artistic Independence

A pivotal period in Moreau's artistic development occurred between 1857 and 1859 when he undertook an extended self-funded journey through Italy. This trip was far more immersive than his earlier visit. He traveled extensively, visiting Rome, Florence, Venice, Naples, and other significant artistic centers. He spent countless hours studying and copying masterpieces in churches and museums, deepening his admiration for artists like Michelangelo, Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, Benozzo Gozzoli, and Vittore Carpaccio. The intricate details, rich colors, and symbolic depth of early Renaissance and Byzantine art particularly captivated him.

During this Italian sojourn, Moreau crossed paths with other French artists, including the young Edgar Degas, with whom he formed a lasting friendship. They shared insights and sketched together, absorbing the lessons of the Italian masters. This period abroad was crucial for Moreau. It allowed him to consolidate his influences, moving beyond the direct tutelage of Picot and Chassériau and the confines of the Paris art scene. He assimilated the grandeur of the Italian tradition but filtered it through his own increasingly personal and introspective lens, solidifying the foundations of his mature style. He returned to Paris not merely as a skilled academic painter, but as an artist with a distinct and complex vision.

The Emergence of a Symbolist Master

By the early 1860s, Moreau began exhibiting works that clearly signaled his departure from mainstream academicism and positioned him as a forerunner of Symbolism. Symbolism, as a literary and artistic movement, emerged in the latter half of the 19th century, largely as a reaction against the perceived materialism and objectivity of Realism and Impressionism. Symbolist artists and writers sought to express subjective emotions, spiritual ideas, and psychological states through suggestion, metaphor, and symbolic imagery, often drawing inspiration from myth, dreams, religion, and the esoteric.

Moreau's art perfectly embodied these concerns. He rejected the Impressionists' focus on capturing fleeting moments of contemporary life and optical sensations. Instead, he delved into the timeless realms of myth and legend, using these ancient narratives as vehicles to explore universal human experiences and complex psychological states. His paintings were conceived not as windows onto the real world, but as portals into an inner reality, a world of dreams, visions, and profound emotional intensity. He believed art should elevate the mind and spirit, conveying ideas that transcended mere appearances.

His approach was deeply personal and intellectual. He meticulously researched his subjects, immersing himself in classical texts, biblical stories, and medieval legends. Yet, his interpretations were never purely illustrative. He imbued traditional narratives with layers of personal meaning, often focusing on moments of psychological tension, spiritual revelation, or enigmatic confrontation. His work invited contemplation, suggesting meanings rather than stating them outright, leaving room for the viewer's imagination to engage with the complex symbolism woven into each composition.

Myth and Legend Reimagined: Oedipus and the Sphinx

Moreau achieved significant public recognition with his painting Oedipus and the Sphinx, exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1864. This work marked a turning point in his career and is considered a landmark of early Symbolism. The painting depicts the famous mythological encounter where the hero Oedipus confronts the enigmatic Sphinx, who poses a riddle to travelers, killing those who cannot answer.

Moreau's interpretation is intensely psychological. Rather than depicting a dynamic struggle, he presents a static, almost hypnotic confrontation. Oedipus, rendered with classical precision, gazes intently into the eyes of the Sphinx, who clings to his chest, her lion body and female head rendered with sharp detail. The background features a chasm littered with the remains of previous victims, emphasizing the deadly nature of the encounter. The atmosphere is one of profound stillness and intellectual tension. The Sphinx represents not just a physical monster but the enigma of life, fate, and knowledge, while Oedipus embodies humanity's quest for understanding, facing the abyss of the unknown. The painting's blend of academic finish, intricate detail, and intense psychological drama captivated the Salon audience and critics, establishing Moreau's reputation as a major artistic force.

The Enigmatic Femme Fatale: Salome and The Apparition

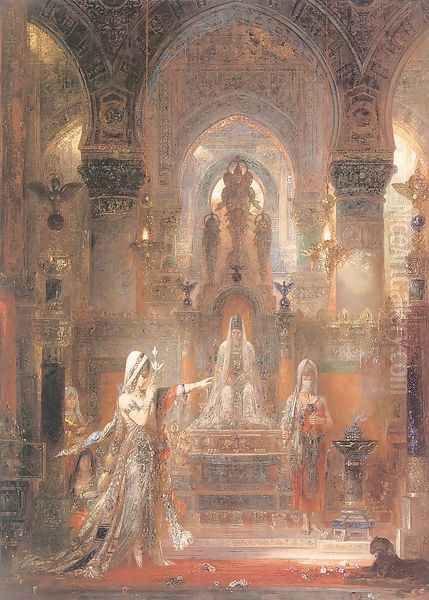

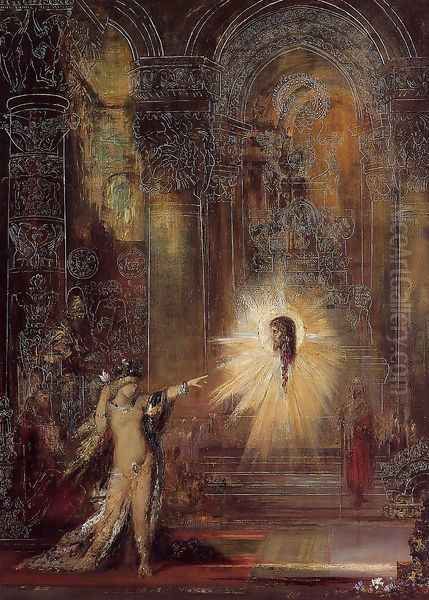

Among Moreau's most famous and recurring subjects is the biblical figure of Salome, the Judean princess whose seductive dance led to the beheading of John the Baptist. Moreau returned to this theme multiple times, most notably in his 1876 painting Salome Dancing Before Herod and the haunting watercolor The Apparition, also from around 1876. These works became iconic representations of the femme fatale – the alluring yet dangerous woman – a figure that fascinated many Symbolist artists and writers.

In Salome Dancing Before Herod, Moreau presents a scene of decadent opulence. Salome, adorned with jewels and elaborate garments, stands poised before a brooding Herod Antipas in a fantastical palace setting that blends Byzantine, Indian, and imaginary architectural elements. The atmosphere is heavy with sensuality and impending doom. Moreau lavishes attention on the intricate details of fabrics, jewels, and architectural ornamentation, creating a visually stunning yet morally ambiguous spectacle. Salome here embodies a complex mix of innocence, erotic power, and destructive potential.

The Apparition offers a more visionary and hallucinatory interpretation. Salome stands frozen, pointing towards a spectral, levitating head of John the Baptist, dripping blood and surrounded by an ethereal glow. The setting is similarly ornate and mysterious. This work moves further into the realm of dream and psychological horror, depicting the consequences of Salome's actions manifesting as a terrifying vision. Moreau's Salome paintings, with their rich textures, exoticism, and exploration of themes like desire, power, and guilt, became immensely influential, cementing his image as a master of the mysterious and the sensual.

Apotheosis of the Divine: Jupiter and Semele

One of Moreau's late masterpieces, completed around 1894-1895, is the monumental and dazzling Jupiter and Semele. This painting depicts the tragic myth of the mortal princess Semele, who, persuaded by a jealous Juno, asks her lover Jupiter (Zeus) to appear to her in his full divine glory. Unable to withstand the overwhelming power and radiance of the god, Semele is consumed by his lightning bolts, though Jupiter manages to save their unborn child, Bacchus (Dionysus).

Moreau's canvas is an explosion of detail and symbolic imagery. Jupiter sits enthroned in majestic splendor, his form radiating light, surrounded by a profusion of mythological figures, divine beings, and symbolic elements drawn from various traditions. The dying Semele collapses at his feet, overwhelmed by the divine presence. The composition is incredibly dense, almost overwhelming the viewer with its intricate ornamentation, rich colors, and complex iconography. It represents a synthesis of Moreau's lifelong interests – mythology, mysticism, intricate decoration, and the exploration of the relationship between the human and the divine. The painting functions almost as a visual encyclopedia of myth, a testament to Moreau's erudition and imaginative power, pushing the boundaries of representation towards an almost abstract accumulation of form and color.

Exploring Other Worlds: Diverse Themes and Works

While Oedipus, Salome, and Jupiter and Semele are among his most celebrated works, Moreau's oeuvre encompasses a wide range of subjects drawn from diverse sources. He frequently depicted scenes from Greek mythology, such as The Daughters of Thespius (1853), an early work showing his interest in complex group compositions and classical themes treated with a certain medievalizing sensibility. He also explored biblical narratives, often choosing moments of intense emotion or spiritual significance, as seen in works related to the Passion of Christ or figures like Moses.

His interest in literature extended to medieval legends and Renaissance poetry. A painting like Hesiod and the Muse (c. 1891) explores the theme of artistic inspiration, depicting the ancient Greek poet receiving divine guidance. Moreau was also drawn to allegorical subjects, creating works that personified abstract concepts. Furthermore, his travels and studies informed works with exotic or historical settings, reflecting the 19th-century fascination with Orientalism, though always filtered through his unique imaginative lens. He was also a master watercolorist, producing numerous works in this medium that possess a fluidity and luminosity distinct from his oils, such as the aforementioned The Apparition. His preparatory drawings and sketches reveal a meticulous working process and a superb command of line.

The Alchemy of Color and Line: Moreau's Technique

Moreau's artistic style is characterized by a unique combination of meticulous technique and visionary imagination. His use of color is one of his most distinctive features. He employed a rich, vibrant palette, often applying paint in thick impasto or delicate glazes to achieve jewel-like effects. His colors are rarely purely naturalistic; instead, they serve an expressive and symbolic purpose, contributing to the otherworldly atmosphere of his paintings. He juxtaposed intense hues – deep reds, blues, greens, and golds – creating surfaces that shimmer with light and intricate detail.

His draftsmanship, honed through academic training and extensive copying, was precise and controlled, particularly in the rendering of figures and architectural elements. However, he often combined this precision with areas of looser brushwork or heavily textured surfaces, adding complexity and visual richness. Moreau was a master of ornamentation. His paintings are frequently filled with elaborate patterns, intricate jewelry, fantastical architecture, and exotic flora, creating a sense of luxurious density. This decorative quality, sometimes criticized by proponents of realism, was integral to his symbolic intent, suggesting hidden meanings and contributing to the dreamlike quality of his scenes. His compositions are often complex and layered, guiding the viewer's eye through a dense tapestry of forms and symbols. He skillfully blended influences from diverse sources – Renaissance painting, Byzantine mosaics, Persian miniatures, Indian art – into a cohesive and highly personal style.

A Life Dedicated to Art: Personality and Process

Gustave Moreau led a life largely devoted to his art, cultivating an image of a dedicated, somewhat reclusive figure. While not a complete hermit – he exhibited at the Salon, maintained friendships, and later taught – he seemed most comfortable within the sanctuary of his home and studio on the Rue de La Rochefoucauld in Paris. Contemporaries described him as living amidst his artistic creations, somewhat detached from the hustle and bustle of modern Parisian life, preferring the company of myths and legends. Joris-Karl Huysmans, in his novel À rebours (Against Nature), famously depicted his decadent protagonist Des Esseintes as an admirer of Moreau's art, reinforcing the perception of Moreau as an artist catering to refined, introspective tastes.

His personal life was relatively quiet. He never married but maintained a long and devoted relationship with Alexandrine Dureux, who entered his household initially as a companion for his mother and remained with him as his housekeeper, confidante, and occasional model for nearly three decades until her death in 1890. Moreau was deeply attached to his parents, living with them until their deaths.

His working process was known to be meticulous and painstaking. He produced numerous preparatory drawings, sketches, and oil studies for his major compositions, experimenting with different arrangements and details. The sheer volume of studies found in his studio after his death attests to his rigorous approach. For instance, hundreds of preparatory works exist for The Apparition. He was also known to be reluctant to sell his major works, preferring to keep them around him. While he did sell some pieces, particularly earlier in his career or to close friends and discerning collectors, he seemed to view his most important creations as part of an ongoing personal dialogue, constantly refining and living with them.

The Teacher of Titans: Moreau at the École des Beaux-Arts

Despite his somewhat withdrawn nature, Moreau took on a significant public role late in his career when he was appointed professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1891, succeeding his friend Elie Delaunay. He held this position until his death in 1898 and proved to be an exceptionally influential and beloved teacher. His approach contrasted sharply with the rigid methods of many other academic instructors. Moreau encouraged his students to find their own artistic voices, emphasizing the importance of imagination, emotion, and personal expression alongside technical skill.

His studio became a vibrant hub for young artists seeking alternatives to strict academicism. Among his most famous pupils were Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault, key figures in the development of Fauvism and modern Expressionism. Both artists retained deep respect and affection for Moreau throughout their lives. Matisse later recalled Moreau's liberating advice: "You were born to simplify painting." Rouault spoke of Moreau's studio as a place of intellectual and artistic freedom. Other notable artists who passed through his studio included Albert Marquet and Henri Evenepoel. Moreau's open-mindedness and focus on individual development nurtured a generation of artists who would go on to revolutionize painting in the early 20th century. His students' subsequent fame significantly contributed to the posthumous appreciation of Moreau's own pioneering role.

Navigating the Art World: Moreau and His Contemporaries

Moreau occupied a unique position within the complex art world of late 19th-century Paris. While rooted in academic training, his work diverged significantly from the historical paintings favored by the official Salon and the Neoclassical ideals upheld by artists like Ingres earlier in the century. He admired the Romanticism of Delacroix, particularly his use of color and dramatic themes, and was profoundly influenced by his mentor Chassériau.

His relationship with Impressionism was one of mutual distance. Moreau's focus on imagination, myth, and meticulous finish was antithetical to the Impressionists' emphasis on capturing contemporary life, fleeting light effects, and spontaneous brushwork. While he maintained friendships with artists like Degas, who shared an appreciation for classical draftsmanship, Moreau's artistic path ran parallel rather than intersecting with the Impressionist revolution.

He is best understood in relation to the broader Symbolist movement. He shared thematic concerns with other Symbolist painters like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, known for his serene, allegorical murals, and Odilon Redon, whose mysterious charcoals and pastels explored the world of dreams and the subconscious. However, Moreau's style remained distinct, characterized by its greater emphasis on narrative complexity, historical detail, and jewel-like surfaces. While Post-Impressionist artists like Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin were also moving beyond naturalism towards more subjective and formally experimental art, Moreau's approach remained more tied to literary and mythological sources and a high degree of finish, though his late works sometimes displayed a surprising freedom of handling that bordered on abstraction.

Echoes Through Time: Influence on Later Art

Gustave Moreau's influence extended far beyond his own lifetime and the immediate circle of his students. His emphasis on color as an expressive force, encouraged in his teaching, directly contributed to the emergence of Fauvism around 1905. Matisse, Rouault, Marquet, and others applied Moreau's lessons about liberated color to contemporary subjects, creating works of startling intensity.

His status as a precursor to Surrealism was explicitly acknowledged by the movement's leader, André Breton, who admired Moreau's exploration of the irrational, the dreamlike, and the marvelous. Surrealist artists like Salvador Dalí were drawn to the hallucinatory quality and complex psychological undertones of Moreau's work. The intricate detail, ambiguous narratives, and fusion of the beautiful and the grotesque in Moreau's paintings resonated with the Surrealist fascination with the subconscious mind.

Moreau's impact was also felt in literature. Writers like Joris-Karl Huysmans and Jean Lorrain championed his work. The great French novelist Marcel Proust was an admirer, and echoes of Moreau's aesthetic sensibility, particularly the fascination with intricate detail and evocative symbolism, can be discerned in Proust's monumental novel In Search of Lost Time. The Cuban Parnassian poet José María de Heredia was also inspired by his art. Furthermore, Moreau's decorative richness and symbolic complexity find parallels in the work of later artists associated with Symbolism and Art Nouveau across Europe, such as the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt or the English Pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones, who shared interests in myth, legend, and ornate design.

The House of Dreams: The Musée National Gustave Moreau

Perhaps the most tangible aspect of Moreau's legacy is the Musée National Gustave Moreau, located in his former home and studio at 14 Rue de La Rochefoucauld in Paris. In his will, Moreau bequeathed the building and its contents – thousands of paintings, watercolors, drawings, and studies, along with personal belongings – to the French state, on the condition that it be preserved as a museum dedicated to his work. Opened to the public in 1903, five years after his death, the museum offers an unparalleled immersion into the artist's world.

The museum preserves not only finished masterpieces but also a vast collection of preparatory works, unfinished canvases, and sketches, providing invaluable insight into Moreau's creative process. The densely hung walls, particularly in the large upper-floor studios Moreau had built, evoke the atmosphere in which he lived and worked. Visitors can see his personal apartments, preserved much as they were during his lifetime, complete with furniture, books, and mementos. The museum stands as a unique monument to a single artist, a testament to Moreau's dedication to his vision and his desire to share his artistic universe with posterity. It remains an essential site for understanding his art and the Symbolist movement.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Vision and Mystery

Gustave Moreau remains a compelling and somewhat enigmatic figure in art history. He was an artist who bridged traditions, drawing deeply from the academic and Renaissance past while simultaneously anticipating key aspects of modern art. His commitment to imagination, symbolism, and the exploration of the inner world positioned him as a central figure in the Symbolist movement, offering a powerful alternative to the dominant trends of Realism and Impressionism.

Through his intricate and opulent paintings, Moreau created a unique visual language to explore timeless themes of myth, spirituality, desire, and mortality. His work continues to fascinate viewers with its combination of technical brilliance, complex iconography, rich color, and mysterious atmosphere. As a teacher, he fostered a spirit of individuality that helped launch the careers of major figures in 20th-century art. His legacy, preserved in his captivating artworks and the unique museum dedicated to his life and work, secures his place as a visionary artist whose intricate dreams continue to resonate in the modern world.