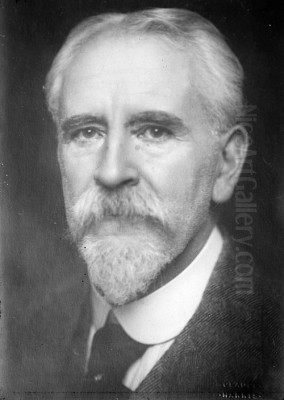

Frank Bernard Dicksee, later Sir Frank Dicksee, stands as a prominent figure in the landscape of late Victorian and Edwardian art. Born on November 27, 1853, in London, and passing away on October 17, 1928, Dicksee's career spanned a period of significant artistic transition. He is celebrated for his meticulously crafted paintings depicting dramatic historical and legendary scenes, chivalric romance, and elegant society portraits, all rendered with a characteristic richness of color and a deep emotional resonance. His commitment to the academic tradition and his romantic sensibilities placed him as a stalwart against the rising tide of Modernism, making him a fascinating subject for art historical study.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Frank Dicksee was born into an environment steeped in artistic pursuit. His father, Thomas Francis Dicksee (1819–1895), was a notable painter, known for his portraits and historical genre scenes. This familial influence was profound; Frank's brother, Herbert Thomas Dicksee (1862–1942), also became a painter, particularly known for his depictions of animals, and his sister, Margaret Isabel Dicksee (1858–1903), was an accomplished artist as well. This upbringing provided Frank with an early and intimate exposure to the techniques and intellectual currents of the art world.

His formal artistic education commenced in 1870 when he enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Here, he quickly distinguished himself as a student of exceptional talent. In 1872, he was awarded a silver medal for a drawing from the antique, a foundational exercise for aspiring academicians. His prowess continued to develop, culminating in 1875 when he received the coveted gold medal for his historical painting, Elijah confronting Ahab and Jezebel in Naboth's Vineyard. This accolade was a significant marker of his early promise and set the stage for a distinguished career within the Royal Academy's esteemed circles.

The Illustrator and Emerging Painter

Before fully establishing himself as a painter in oils, Dicksee engaged in illustration work, a common path for many artists of the period to gain financial stability and public recognition. He contributed illustrations to popular periodicals such as The Graphic and Cornhill Magazine. His illustrative work extended to literary classics, where his romantic and dramatic inclinations found fertile ground. He created memorable images for editions of Longfellow's Evangeline, and notably, for Shakespearean plays, including Othello and Romeo and Juliet. This experience in narrative illustration honed his skills in composition, character portrayal, and the visual interpretation of textual sources, elements that would become hallmarks of his later paintings.

His transition to oil painting saw him explore themes that resonated with Victorian sensibilities. Medievalism, chivalry, and romantic love were recurrent subjects, often imbued with a sentimental or melancholic atmosphere. His technical proficiency, characterized by a smooth finish, meticulous attention to detail, and a vibrant palette, aligned him with the prevailing tastes of the era, which still largely favored narrative clarity and polished execution over impressionistic experimentation.

Themes of Chivalry, Romance, and Legend

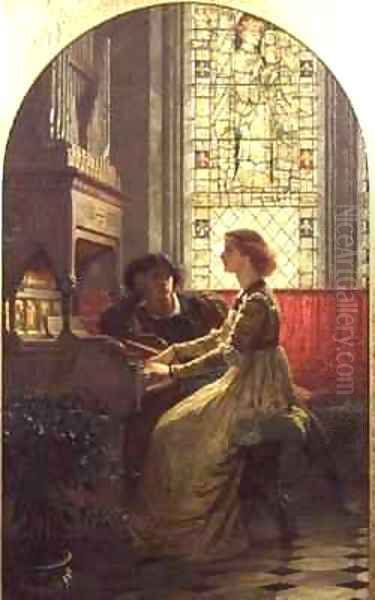

Dicksee's oeuvre is rich with subjects drawn from literature, legend, and history, often focusing on moments of high emotional drama or poignant sentiment. His painting Harmony (1877), exhibited at the Royal Academy, was an early success that captured public imagination. It depicts a young woman playing an organ in a dimly lit, stained-glass windowed room, with a young man leaning over her, listening intently. The mood is one of serene, romantic absorption, and the painting's aesthetic, with its medievalizing details and rich, jewel-like colors, shows a clear affinity with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and their followers.

Works like Chivalry (1885) exemplify his engagement with medieval romance. This painting portrays a knight in shining armor rescuing a distressed damsel from two assailants in a forest setting. The composition is dynamic, the figures idealized, and the narrative clear and heroic. It speaks to the Victorian fascination with an idealized past, where honor and valor were paramount virtues.

His literary paintings often drew from Shakespeare and Arthurian legends. The Funeral of a Viking (1893), a dramatic and somber portrayal of a Norse chieftain's ship burial, showcases his ability to handle large, complex compositions and evoke a powerful sense of historical atmosphere. Another significant work, La Belle Dame Sans Merci (1901), inspired by John Keats's poem, depicts a knight enthralled by an enigmatic and beautiful fairy queen, capturing the poem's themes of fatal enchantment and unrequited love with a lush, dreamlike quality. This painting, with its meticulous detail and romantic intensity, is often cited as one of his masterpieces.

Portraiture and Society Painting

While renowned for his narrative works, Frank Dicksee was also a highly sought-after portrait painter, particularly of elegant women from affluent society. His portraits are characterized by their refined execution, flattering portrayals, and an ability to capture the sitter's personality and social standing. He adeptly rendered luxurious fabrics, intricate jewelry, and fashionable attire, elements that appealed to his clientele.

These portraits, while perhaps less overtly dramatic than his historical scenes, demonstrate his versatility and his keen eye for contemporary fashion and social nuance. They provide a valuable visual record of Edwardian high society. His skill in this genre contributed significantly to his financial success and his standing within the art establishment. Later in his career, particularly during and after World War I, he also undertook portraits of military figures, adapting his style to convey a sense of dignity and authority.

Artistic Style: Pre-Raphaelite Echoes and Academic Polish

Frank Dicksee's style can be seen as a continuation and adaptation of several artistic currents. He is often associated with the later phase of Pre-Raphaelitism, though he was not a member of the original Brotherhood. Like John Everett Millais in his later career, or Arthur Hughes, Dicksee shared the Pre-Raphaelite love for literary and historical subjects, meticulous detail, brilliant color, and a certain romantic intensity. The influence of artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones can be discerned in the often melancholic beauty of his female figures and the decorative richness of his compositions.

However, Dicksee's work also maintained a strong allegiance to the academic tradition championed by the Royal Academy. His draughtsmanship was impeccable, his compositions carefully structured, and his finish highly polished, traits valued by academicians like Lord Frederic Leighton and Sir Edward Poynter, both of whom served as Presidents of the Royal Academy before him. Dicksee's art, therefore, represents a synthesis: the romanticism and narrative focus of the Pre-Raphaelites filtered through a more conventional, academic lens. He did not embrace the more radical social or artistic tenets of the early Pre-Raphaelites but rather adopted their aesthetic appeal for subjects that resonated with Victorian ideals of beauty, morality, and sentiment.

Compared to contemporaries like John William Waterhouse, who also explored mythological and romantic themes with a similar Pre-Raphaelite-influenced style, Dicksee's work often possessed a slightly more formal, less overtly Symbolist quality. He was less inclined towards the enigmatic or psychologically intense imagery of some of his peers, preferring a clearer narrative and a more straightforward emotional appeal. His approach differed significantly from the impressionistic innovations of artists like James McNeill Whistler or the burgeoning Post-Impressionist movements that were gaining traction towards the end of his career.

The Royal Academy and a Stand Against Modernism

Frank Dicksee's career was inextricably linked with the Royal Academy. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1881 and became a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1891. His dedication to the institution and his adherence to its artistic principles culminated in his election as President of the Royal Academy (PRA) in 1924, succeeding Sir Aston Webb. This was the pinnacle of academic artistic achievement in Britain.

As President, Dicksee was a staunch defender of traditional artistic values. He viewed the rise of Modernist movements, such as Cubism and Fauvism, with considerable skepticism, if not outright hostility. He believed these new forms of art represented a departure from skill, beauty, and intelligibility, which he considered essential to great art. His presidential addresses often lamented the perceived decline in artistic standards and championed the enduring importance of representational art and technical proficiency. This conservative stance, while reflecting the views of many within the Academy, placed him in opposition to the avant-garde and contributed to the perception of academic art as increasingly outmoded by the early 20th century.

In recognition of his services to art and his position, he was knighted in 1925. In 1927, he was further honored by King George V, who appointed him a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO), a personal gift of the monarch. These accolades underscored his esteemed position within the British cultural establishment.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Beyond those already mentioned, several other works highlight Dicksee's artistic range and thematic preoccupations. The Symbol (1881) is a poignant depiction of a young woman placing a floral tribute at a religious shrine, its rich colors and emotional sincerity resonating with viewers. Romeo and Juliet (1884), one of his most famous Shakespearean interpretations, captures the passion and tragedy of the lovers in a tender balcony scene, rendered with his characteristic attention to costume and romantic atmosphere.

The Two Crowns (1900) is a more allegorical work, depicting a young king on horseback, triumphant in a procession, looking up to see a vision of Christ crowned with thorns, offering a spiritual crown. This painting, with its moralizing theme and grand composition, was highly acclaimed and purchased for the Chantrey Bequest, a fund for acquiring art for the nation, now part of the Tate collection. It reflects the Victorian era's interest in art that conveyed uplifting or didactic messages.

His less famous works, including numerous sketches and studies, reveal his meticulous working process. These preparatory drawings, often detailed and carefully executed, demonstrate his commitment to anatomical accuracy and compositional planning. While his oil paintings command higher prices and greater public attention, his works on paper are essential for understanding his artistic development and technical mastery. Some of his works, like The Pirate's Funeral, exhibited in 1921, found homes in provincial galleries, such as the Manchester Art Gallery, contributing to the dissemination of his art beyond London.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

To fully appreciate Dicksee's position, it is useful to consider him in the context of his contemporaries. He worked alongside other prominent Victorian narrative painters such as Lawrence Alma-Tadema, known for his scenes of classical antiquity, and Briton Rivière, who often incorporated animals into his historical and biblical subjects. While Dicksee shared their commitment to detailed realism and narrative clarity, his thematic focus on medieval romance and chivalry set him apart.

He was also a contemporary of the great portraitist John Singer Sargent, whose bravura brushwork and psychological insight offered a more modern approach to portraiture, contrasting with Dicksee's more polished and idealized style. The social realist painters, such as Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer, focused on contemporary social issues, a path Dicksee largely avoided, preferring the escapism of historical and legendary themes. Even within the realm of romantic and mythological painting, artists like George Frederic Watts pursued a more overtly Symbolist and allegorical direction. Dicksee's art, while deeply romantic, remained more grounded in narrative and traditional aesthetics. His circle would have also included academic sculptors like Hamo Thornycroft and Alfred Gilbert, who shared a similar classical grounding.

Legacy and Reassessment

Frank Dicksee died suddenly in London on October 17, 1928, at the age of 74. At the time of his death, his style of art was already considered old-fashioned by many critics and emerging artists who were embracing Modernism. For several decades following his death, Victorian academic painting, including Dicksee's, suffered a period of critical neglect and was often dismissed as sentimental or irrelevant.

However, from the latter part of the 20th century onwards, there has been a significant reassessment of Victorian art. Scholars and the public alike have begun to appreciate anew the technical skill, narrative power, and aesthetic beauty of works by artists like Dicksee. His paintings are now highly sought after by collectors, and exhibitions of Victorian art regularly feature his contributions.

His enduring appeal lies in his ability to evoke a sense of romance, drama, and idealized beauty. His works transport viewers to worlds of chivalric knights, tragic lovers, and legendary heroes. While his opposition to Modernism may have typecast him as a conservative figure, his dedication to his craft and his creation of memorable and emotionally resonant images have secured his place in the history of British art. He remains a key representative of the late Victorian romantic tradition, an artist who skillfully blended academic precision with a deeply felt poetic sensibility. His paintings continue to captivate audiences with their storytelling, their exquisite detail, and their unapologetic embrace of beauty and sentiment.