Willi Jaeckel, born on February 10, 1888, in Breslau, Silesia (then Germany, now Wrocław, Poland), and who tragically died on January 30, 1944, in Berlin, stands as a significant yet often embattled figure in the landscape of German Expressionism. A painter and printmaker of considerable talent, his life and career were deeply intertwined with the tumultuous socio-political currents of early 20th-century Germany. His work, characterized by its emotional intensity and often stark portrayal of the human condition, reflects both the artistic innovations of his time and the profound anxieties of an era marked by war and ideological conflict. Jaeckel's journey from a promising student to a celebrated artist, and subsequently a victim of Nazi persecution, offers a poignant lens through which to view the fate of modern art under totalitarianism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Willi Jaeckel's path to art was not initially straightforward. His father, a public land manager, had envisioned a career for his son as a forest administrator. However, health concerns redirected the young Jaeckel towards a different vocation. This pivotal change led him to enroll at the art school in Breslau, where he studied from 1906 to 1908. This foundational period provided him with the initial technical skills and exposure to artistic ideas that would shape his future.

Seeking to further his education and immerse himself in a more dynamic artistic environment, Jaeckel moved to Dresden. In 1908, he began his studies at the prestigious Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, a crucible for many emerging talents. He became a master student under the tutelage of Otto Gußmann, a notable decorative painter and professor at the academy. Gußmann, known for his work in applied arts and monumental painting, likely imparted a strong sense of composition and technical proficiency to Jaeckel, even as Jaeckel's own style would gravitate towards the more radical forms of Expressionism. The Dresden environment, with its rich artistic heritage and burgeoning modernist scene, including the presence of the Die Brücke group (though they had largely moved to Berlin by then), undoubtedly fueled his artistic development.

Emergence in the Berlin Art Scene and Expressionist Style

By 1913, Willi Jaeckel had relocated to Berlin, the pulsating heart of Germany's avant-garde. It was here that his career truly began to flourish. He quickly became associated with the Berlin Secession, a progressive group of artists who had broken away from the traditional, state-sponsored art institutions. Founded by artists like Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt, the Secession championed modern art and provided a crucial platform for younger, more experimental artists. Jaeckel's involvement with this group signaled his alignment with the modernist cause.

His artistic voice found its most potent expression in the language of Expressionism. This movement, which prioritized subjective feeling and inner vision over objective representation, resonated deeply with Jaeckel. His works from this period are characterized by bold, often distorted forms, dynamic compositions, and a heightened emotional register. He explored a range of human experiences, often focusing on themes of struggle, passion, and spirituality. His printmaking, particularly lithography and etching, became an important medium for disseminating his powerful imagery, allowing for stark contrasts and expressive lines that suited his artistic temperament.

One of his earliest acclaimed works, Kampf (The Struggle or The Fight), created around 1912, exemplifies his burgeoning Expressionist style. The painting, depicting a muscular, nude male figure in a moment of intense exertion, was considered a significant success. It showcased his ability to convey raw power and psychological tension through dramatic figuration, a hallmark that would continue throughout his oeuvre. This work, with its focus on the primal energy of the human body, set the tone for much of his subsequent explorations of the human condition.

Themes of War, Society, and Humanity

The cataclysm of World War I profoundly impacted Jaeckel, as it did many artists of his generation. While some Expressionists, like Franz Marc or August Macke, initially embraced the war with a sense of Futurist fervor before meeting tragic ends, others, including Jaeckel, developed a critical and often horrified perspective. His art began to reflect the trauma and disillusionment of the war years and their aftermath. Anti-war themes became prominent in his work, not through literal depictions of battle, but through allegorical representations of suffering, loss, and the brutalization of humanity.

Jaeckel's social critique extended beyond the immediate horrors of war. He was keenly observant of the societal shifts and tensions of the Weimar Republic. His portraits and figure studies often captured a sense of unease and introspection, reflecting the psychological landscape of a nation grappling with defeat, economic instability, and rapid social change. Artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix were more overtly satirical in their critique of Weimar society, but Jaeckel's work, while perhaps less direct, conveyed a similar underlying disquiet through its expressive intensity.

His exploration of humanity was multifaceted. He depicted scenes of maternal love, such as in his print Mutter mit Kind (Mother with Child), but also delved into darker, more complex aspects of human nature. His figures are rarely idealized; instead, they are imbued with a raw, often unsettling vitality. This unflinching approach to the human form and psyche placed him firmly within the Expressionist tradition, alongside artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, and Max Beckmann, who similarly sought to unmask the inner realities of modern existence.

Recognition and the "New Woman"

Despite the often challenging nature of his subjects, Jaeckel achieved considerable recognition during the Weimar years. In 1915, he became a member of the prestigious Prussian Academy of Arts, a significant honor that underscored his standing in the German art world. He was also an active participant in the Freie Secession, a splinter group from the Berlin Secession that continued to champion avant-garde art.

A notable achievement came in 1928 when he was awarded the "Georg-Schlick-Preis" by the Verein Berliner Künstler (Association of Berlin Artists). This prize was bestowed for a portrait that was lauded as "the most beautiful German woman's portrait." The painting depicted a woman with short, bobbed hair and a short skirt, embodying the image of the "New Woman" (Neue Frau) that had become a cultural icon of the Roaring Twenties. This figure represented a modern, emancipated femininity, and Jaeckel's portrayal captured the spirit of the age, demonstrating his ability to engage with contemporary social archetypes. This success showed a different facet of his work, one that could engage with contemporary ideals of beauty and modernity, alongside his more somber Expressionist explorations.

The Nazi Era and "Degenerate Art"

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933 marked a devastating turning point for modern art in Germany, and for Willi Jaeckel personally. The Nazi regime, with its reactionary cultural ideology, condemned Expressionism and other avant-garde movements as "degenerate" (Entartete Kunst). Artists who did not conform to the officially sanctioned style of heroic realism were persecuted, their works removed from museums, sold abroad, or destroyed, and they were often forbidden to work or exhibit.

Jaeckel, with his powerful, emotionally charged, and often critical art, was an inevitable target. In 1933, he was appointed as an associate professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts, a position that should have offered security. However, the Nazi cultural purges quickly impacted his career. His teaching position was cancelled. Following protests from his students, he was briefly reinstated, only to be definitively dismissed shortly thereafter. This effectively ended his academic career and signaled the increasing hostility of the regime towards his work. Many of his students were unable to graduate due to these disruptions.

In 1937, the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition was staged in Munich, designed to vilify modern art. Hundreds of Jaeckel's works were confiscated from German museums. Some sources indicate that over 200 of his pieces were seized. Many of these were subsequently sold off or, tragically, destroyed. This official condemnation was a severe blow, both professionally and personally.

Despite the persecution, Jaeckel continued to create art, though often in a more circumspect manner. A notable work from this period is Plowman in the Evening (Abendlicher Pflüger), created in 1939. This painting, depicting a farmer tilling the soil, ostensibly engaged with the Nazi "Blood and Soil" (Blut und Boden) ideology, which glorified rural life and agrarianism. However, art historians suggest that Jaeckel's treatment of the theme was subtly critical or ironic, perhaps a coded commentary on the regime's propaganda. Even so, the very act of creating art that could be interpreted through the lens of official ideology, while simultaneously being a "degenerate" artist, highlights the complex and dangerous tightrope many artists had to walk during this dark period. Other artists like Emil Nolde, despite early sympathies with some aspects of National Socialism, also found themselves branded as "degenerate" and faced similar prohibitions.

Artistic Collaborations and Circles

Throughout his career, Jaeckel was part of various artistic circles and engaged in collaborations. His time on the Baltic island of Hiddensee, a popular retreat for artists and intellectuals, brought him into contact with figures such as the writer Gerhart Hauptmann, and fellow artists like Elisabeth Büchen, Elsa Wagner, and Asta Niemann. He was also a frequent visitor to the home of Arnold Gustavs, another Hiddensee resident and chronicler of the island's artistic life. These interactions, while not always formal collaborations, provided a supportive and stimulating environment.

A more direct artistic collaboration involved his participation in the multi-volume erotic print portfolio Der Venuswagen (The Chariot of Venus). This project, curated by Wolfgang Gurlitt, brought together a number of prominent artists, including Lovis Corinth, Richard Janthur, Georg Walter Rössner, Franz Christophe, Paul Scheurich, Wilhelm Wagner, and Willi Geiger. Each artist contributed prints to this collection, which explored themes of eroticism and mythology. Jaeckel's involvement underscores his versatility and his engagement with a broader range of artistic themes prevalent at the time. He also reportedly contributed to a portfolio titled Sappho, which likely also featured erotic themes, a common subject for limited-edition print portfolios that allowed artists more freedom of expression. Such portfolios were often produced for a select group of collectors.

His correspondence also offers glimpses into his professional life. A letter from the Bahls H. Keksfabrik (a biscuit company that was also a patron of the arts) to the Kunsthaus Lempertz (an auction house) found among his papers suggests the kind of commercial and institutional interactions that were part of an artist's career, even amidst political turmoil.

Later Works, War's Destruction, and Tragic End

The final years of Willi Jaeckel's life were overshadowed by World War II and the escalating destruction it brought to Germany. Despite the dangers and the official disapproval of his art, he continued to work. Among his later projects was a significant four-part mural for the Bacchus Cellar of the Rheinhotel Dreesen in Bad Godesberg, completed around 1936-1937. This commission, surprisingly public for an artist deemed "degenerate," suggests that some patrons or pockets of influence might have still valued his work, or that the application of cultural policy was not always monolithic. However, these murals were tragically destroyed in 1944.

His personal life was also directly impacted by the war. In 1943, his studio in Berlin was bombed during an Allied air raid. Miraculously, he survived this attack, and some of his works were salvaged. However, fate was not to spare him. On January 30, 1944, Willi Jaeckel was killed during another devastating air raid on Berlin. He was only 55 years old. His death was a tragic loss for German art, cutting short the life of a resilient and powerful artistic voice.

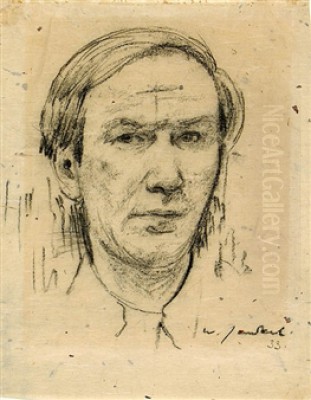

His drypoint etching Christmas (Self-Portrait) from around 1940 offers a poignant glimpse into his state of mind during these dark years. Self-portraits by artists facing persecution or living through wartime often carry a heavy weight of introspection and anxiety, and Jaeckel's was likely no exception, reflecting the somber reality of his existence.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

In the aftermath of World War II and the fall of the Nazi regime, there was a gradual process of re-evaluating the artists and artworks that had been suppressed. Willi Jaeckel's contributions to German Expressionism began to be recognized anew. His work, with its profound emotional depth and its engagement with the critical issues of his time, found its place in the narrative of 20th-century German art.

His paintings and prints are now held in numerous public and private collections, including the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich and other significant German museums. Exhibitions of his work have helped to reintroduce his art to a wider audience and to solidify his reputation as a key figure of his generation. Art historians continue to study his oeuvre, exploring the complexities of his style, his thematic concerns, and his navigation of the treacherous political landscape.

Willi Jaeckel's legacy is that of an artist who remained true to his expressive vision despite immense pressure. He, like Käthe Kollwitz with her powerful anti-war statements, or Max Beckmann with his allegorical triptychs reflecting societal crisis, used his art to delve into the human condition in all its rawness and vulnerability. His life story serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of artistic freedom and the devastating impact of totalitarian ideologies on culture. Yet, the survival of his art and its enduring power testify to the resilience of the creative spirit. He remains an important voice from a generation of German artists who grappled with the profound upheavals of the early 20th century, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its emotional honesty and artistic integrity.