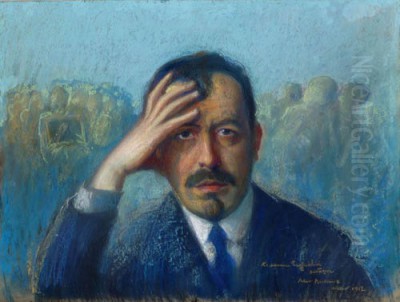

Artur Markowicz stands as a significant figure in early 20th-century Polish art, a painter and printmaker whose life and work were deeply intertwined with the Jewish community of Krakow. Born on March 3, 1872, in Podgórze, then a town near Krakow (now a district within it), Markowicz emerged as a keen observer and sensitive chronicler of a world that, while vibrant in his time, would later face unimaginable devastation. His legacy is preserved in his evocative depictions of daily life, religious observance, and the unique atmosphere of Krakow's historic Jewish quarter, Kazimierz. As a realist painter with discernible influences from Symbolism and Expressionism, Markowicz carved a unique niche for himself, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with historical and artistic significance.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

The late 19th century in Poland, then partitioned among three empires, was a period of complex cultural and national currents. For Polish Jews, it was a time of both flourishing community life and rising social and political tensions. It was into this environment that Artur Markowicz was born. While detailed information about his early childhood and family background is not extensively documented in readily available sources, it is clear that his formative years were spent in the vicinity of Krakow, a city with a rich artistic and intellectual heritage, and one of Europe's oldest and most significant Jewish communities.

His inclination towards art must have manifested early, leading him to seek formal training. The decision to pursue art was not always straightforward in that era, particularly for individuals from traditional backgrounds, but Krakow offered opportunities for aspiring artists. The city was a crucible of Polish culture, and its artistic institutions were gaining prominence, fostering a generation of artists who would contribute to the dynamic Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement, which encompassed literature, visual arts, and music, emphasizing Polish identity, folklore, and often, a turn towards Symbolism and Art Nouveau.

A Pan-European Artistic Education

Markowicz's formal artistic journey began in his native Krakow. He initially enrolled at the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie), a prestigious institution that had nurtured many of Poland's leading artists. However, his time there was reportedly brief. He then pursued studies at the Krakow School of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie) between 1886 and 1895. This period was crucial for laying the foundations of his technical skills and artistic vision.

During his time at the Krakow School of Fine Arts, Markowicz studied under several influential Polish painters. Among his tutors were figures like Ludwig Leopold Löffler, a respected painter and pedagogue known for his historical scenes and portraits. Władysław Łuszczkiewicz, another of his teachers, was a prominent history painter, a disciple of the great Jan Matejko, and a key figure in Krakow's artistic life, also known for his work in art conservation and art history. Florian Cynk, a painter and draftsman, also contributed to Markowicz's education. Perhaps the most towering figure whose influence, even if indirect through his disciples, would have been felt was Jan Matejko himself, the leading Polish historical painter of the 19th century, whose work defined an era and instilled a sense of national narrative in Polish art. Matejko's emphasis on detailed realism and dramatic composition left a lasting mark on Polish art education.

Seeking to broaden his horizons, Markowicz, like many aspiring artists of his generation from Central and Eastern Europe, looked towards major European art centers. He traveled to Munich, which at the time was a significant rival to Paris as an art capital. He enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München). In Munich, he studied under Franz von Stuck, a leading German Symbolist painter, sculptor, and architect. Von Stuck was a co-founder of the Munich Secession and a highly influential teacher whose students included Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. This exposure to German Symbolism and the vibrant Secessionist movement undoubtedly impacted Markowicz's developing style, perhaps encouraging a move beyond strict academic realism towards more evocative and emotionally charged imagery.

His educational peregrinations continued to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world at the turn of the century. From 1900 to 1904, Markowicz studied at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. There, he was a student of Jean-Léon Gérôme, a highly respected master of Academic painting, known for his meticulously detailed historical and Orientalist scenes. Studying under Gérôme would have provided Markowicz with rigorous training in classical draftsmanship and composition, a strong counterpoint to the more avant-garde movements flourishing in Paris at the time, such as Post-Impressionism and the nascent Fauvism. This blend of traditional academic training with exposure to newer artistic currents like Symbolism would inform the unique character of Markowicz's art.

The Heart of Kazimierz: A Studio and a Muse

After his extensive studies abroad, Artur Markowicz returned to Poland around 1904. He chose to settle in Krakow and, significantly, opened his own studio in the historic Jewish quarter of Kazimierz. This decision was pivotal. Kazimierz, with its ancient synagogues, bustling marketplaces, narrow cobblestone streets, and deeply rooted traditions, was not just a location for Markowicz; it became the central subject and enduring inspiration for much of his artistic output.

By establishing his studio in Kazimierz, Markowicz immersed himself in the daily life of its inhabitants. He became an intimate observer of the community, capturing its rhythms, its characters, and its spiritual core. His works from this period are invaluable not only as artistic creations but also as historical documents, offering a glimpse into a way of life that was soon to be irrevocably altered. He was not an outsider looking in, but rather an artist deeply connected to the world he depicted. This connection lent an authenticity and empathy to his portrayals that set them apart.

His early works had reportedly included depictions of fishermen, perhaps reflecting an interest in genre scenes and the lives of working people. However, upon his return and establishment in Kazimierz, his focus shifted decisively towards the Jewish community. He painted street scenes, interiors of synagogues, portraits of rabbis and scholars, depictions of religious festivals, and everyday moments of prayer, study, and commerce. These were not romanticized or exoticized portrayals but rather grounded observations imbued with a quiet dignity.

Artistic Style: Realism Infused with Soul

Artur Markowicz is primarily categorized as a realist painter. His commitment to depicting the world around him with accuracy and detail is evident in his careful rendering of figures, architecture, and light. His training under academic masters like Gérôme provided him with the technical facility to achieve this. However, his realism was not merely photographic or dispassionate. It was a realism tempered by his personal experiences and the artistic currents he had encountered.

Influences of Symbolism, likely absorbed during his time in Munich under Franz von Stuck and prevalent in the Young Poland movement in Krakow (with artists like Jacek Malczewski and Stanisław Wyspiański championing symbolic art), can be discerned in the mood and atmosphere of his paintings. There is often a sense of introspection, a deeper meaning hinted at beyond the surface reality. This is particularly true in his depictions of religious life, where the spiritual dimension is palpable.

Furthermore, elements of Expressionism, a movement gaining traction in the early 20th century, particularly in German-speaking countries, can be seen in his later works. This might manifest in a more subjective use of color, a slight distortion of form for emotional effect, or a focus on the psychological state of his subjects. His style was described as having a strong "originality," suggesting he synthesized these influences into a personal artistic language rather than merely imitating them. He predominantly worked in watercolors and pastels, media that allowed for both precision and a certain fluidity, well-suited to capturing the fleeting moments of life and the subtle play of light in Kazimierz's streets and interiors.

Key Works, Motifs, and Thematic Concerns

While a comprehensive list of individual titled works by Artur Markowicz is not always readily available in general art historical surveys, his oeuvre is characterized by recurring themes and motifs that define his artistic identity. His most celebrated works are undoubtedly his depictions of Kazimierz. These include:

Street Scenes: Markowicz excelled at capturing the unique ambiance of Kazimierz's streets – the ancient buildings, the bustling activity, the interplay of light and shadow. These scenes often feature local inhabitants going about their daily lives, creating a vivid tapestry of the quarter.

Synagogue Interiors and Religious Life: He painted numerous scenes set within synagogues, depicting men at prayer, studying the Torah, or participating in religious ceremonies. These works are rendered with a deep respect for the traditions and spiritual intensity of Jewish religious observance. Figures like "Rabbi at Prayer" or "Talmudic Scholars" are typical of this genre.

Portraits and Character Studies: Markowicz created sensitive portraits of individuals from the Jewish community – elderly men with flowing beards, scholars engrossed in their books, ordinary people whose faces told stories of their lives. These portraits often convey a sense of wisdom, piety, or quiet resilience.

Market Scenes: The vibrant marketplaces of Kazimierz, with their vendors and customers, provided another rich source of inspiration, allowing him to capture the social and economic life of the community.

Beyond these, his earlier interest in fishermen and urban landscapes also forms part of his body of work. A notable specific work mentioned is a poster he designed for an exhibition of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem in 1912. The Bezalel school, founded in 1906 by Boris Schatz with the help of artists like Ephraim Moses Lilien, was a cornerstone in the development of a modern Jewish visual arts tradition in Palestine, and Markowicz's contribution to its promotion highlights his connection to broader Jewish artistic endeavors.

His works are characterized by a subdued palette, often employing earthy tones, grays, and browns, punctuated by moments of warmer color. This palette contributed to the melancholic or contemplative mood often found in his paintings, reflecting perhaps not only the somber realities of life but also a deep sense of history and tradition.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Collections

Artur Markowicz achieved a degree of recognition during his lifetime, with his works being exhibited in various cities across Europe. He participated in exhibitions in Krakow, Warsaw, Lviv (then Lemberg), and other Polish cities. His art was also shown internationally, including in Vienna, Berlin, and Paris, which indicates that his work resonated beyond local circles.

His participation in the activities of the Jewish Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts (Żydowskie Towarzystwo Krzewienia Sztuk Pięknych) was significant. This society played a crucial role in supporting and showcasing Jewish artists in Poland. He exhibited alongside other prominent Polish-Jewish artists of his time, such as Maurycy Gottlieb (though Gottlieb died young in 1879, his influence was profound, and Markowicz may have exhibited with a posthumous showing or alongside his brother Leopold Gottlieb), Roman Kramsztyk, Efraim Seidenbecher, and Menasze Seidenbecher. These artists, each with their own style, collectively contributed to a rich tapestry of Jewish artistic expression in Poland. Other contemporaries in the broader Polish-Jewish art scene included Samuel Hirszenberg, known for his poignant depictions of Jewish life and exile, and later figures like Artur Nacht-Samborski and Jan Gotard.

Today, Artur Markowicz's paintings and prints are held in several important museum collections, primarily in Poland and Israel. These include the National Museum in Krakow, the Historical Museum of Krakow (which has a significant collection related to the city's Jewish heritage), the National Museum in Gdansk, and the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw (formerly the Jewish Historical Institute). His works are also found in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, underscoring his importance in the narrative of Jewish art. The presence of his art in these institutions ensures its preservation and accessibility for future generations and scholars.

The Jerusalem Sojourn

An interesting episode in Markowicz's life was his period of residence in Jerusalem. He lived there from 1907 to 1908. While the specific reasons for this move and the full extent of its impact on his art are not extensively detailed, it is a noteworthy chapter. Jerusalem, the spiritual center of Judaism, would have offered a profoundly different environment from Krakow. The light, the landscape, the ancient stones, and the diverse Jewish communities (Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Mizrahi) living there would have provided new stimuli.

It is plausible that his time in Jerusalem deepened his connection to Jewish themes and perhaps offered a different perspective on Jewish identity and tradition. This period coincided with the early years of the Bezalel Academy, and his connection to it (evidenced by the 1912 poster design) suggests an engagement with the burgeoning artistic life in pre-state Israel. His experiences there may have enriched his understanding of the broader Jewish world, which he then brought back to his continued depictions of Jewish life in Poland. After this sojourn, he returned to Krakow, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Later Years, Legacy, and the Shadow of History

Artur Markowicz continued to paint and exhibit throughout the 1910s and 1920s. His later works are said to have increasingly reflected the "tragic aspects of Jewish life." This could be interpreted in several ways: perhaps a growing awareness of the precariousness of Jewish existence in Eastern Europe, the economic hardships faced by many, or a more personal, melancholic temperament. The interwar period in Poland was one of renewed independence but also of significant social and economic challenges, and rising antisemitism. Artists are often sensitive barometers of their times, and Markowicz's art may have subtly or overtly registered these undercurrents.

He passed away in Krakow on October 23, 1934, at the age of 62. He was buried in the New Jewish Cemetery in Krakow. His death occurred just a few years before the cataclysm of World War II and the Holocaust, which would decimate the Polish-Jewish community he had so devotedly chronicled. In this tragic light, his work acquires an even greater poignancy. His paintings serve as a visual testament to a world that was largely destroyed, preserving the faces, customs, and spirit of Polish Jewry.

Markowicz's legacy lies in his contribution to both Polish art and Jewish art. He was part of a generation of Polish artists who sought to define a modern national art, and within that, he was a key figure among Jewish artists who explored their own cultural identity through their work. He stands alongside artists like Wilhelm Wachtel, who also depicted Galician Jewish life, or Maurycy Trebacz, another painter of Jewish themes. His commitment to realism, enriched by emotional depth, provided an invaluable record of his community. While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his contemporaries from Paris or Vienna, like Chaim Soutine or Marc Chagall who explored Jewish identity in more avant-garde styles, Markowicz's quieter, more observational approach holds its own unique power and importance.

Markowicz in the Context of Polish and Jewish Art

To fully appreciate Artur Markowicz, it is essential to place him within the dual contexts of Polish national art and the specific traditions of Jewish art in Eastern Europe. At the turn of the 20th century, Polish art was vibrant, with the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement in full swing. Artists like Stanisław Wyspiański, a multifaceted genius, Józef Mehoffer, known for his stained glass and paintings, and the symbolist Jacek Malczewski were dominant figures. While Markowicz's style was generally more rooted in realism than the overt symbolism or Art Nouveau aesthetics of some Young Poland artists, he shared their commitment to Polish themes (in his case, a specific segment of Polish society) and a high level of artistic craftsmanship. His contemporary, Olga Boznańska, working in a more introspective, psychological realist style, also achieved international recognition from Krakow.

Within the sphere of Jewish art, Markowicz was part of a broader movement of artists seeking to give visual expression to Jewish life and identity. This was a relatively new phenomenon, as figurative art had traditionally been less central in Jewish religious tradition compared to other cultures. However, the 19th and early 20th centuries saw a flourishing of Jewish artists across Europe. In Eastern Europe, artists like Yehuda Pen (Chagall's first teacher in Vitebsk) were dedicated to depicting shtetl life. Markowicz's focus on the urban Jewish environment of Kazimierz offered a specific lens on this world. His work can be compared to that of other Jewish artists who documented their communities, but his particular blend of academic skill, realist observation, and subtle emotional undertones gives his work its distinctive character.

He was not an artist of radical manifestos or avant-garde breakthroughs in the vein of the Parisian modernists. Instead, his contribution was one of dedicated, sensitive observation and skillful representation. He chronicled the everyday, the spiritual, and the communal, creating a body of work that is both a historical record and a collection of deeply human portrayals.

Conclusion: An Enduring Witness

Artur Markowicz's art serves as an enduring window into the soul of Krakow's Kazimierz before its darkest chapter. His paintings and prints are more than just depictions of a bygone era; they are imbued with the life, faith, and humanity of the people he knew and observed. Through his dedicated realism, touched by the introspective qualities of Symbolism and the emotional resonance of early Expressionism, he captured the essence of a community. His education across Europe – from the historical traditions of Krakow and the academic rigor of Paris to the symbolist currents of Munich – equipped him with a versatile artistic language.

His choice to make Kazimierz his artistic home and primary subject demonstrates a profound connection to his heritage and his people. In a world where Jewish life in Eastern Europe is often viewed through the tragic lens of the Holocaust, Markowicz's work reminds us of the vibrancy, richness, and deep-rooted traditions that existed for centuries. He remains a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure whose art continues to speak to us of history, identity, and the enduring power of the human spirit. His legacy is that of a faithful witness, a skilled artist, and a chronicler of a world that, though changed forever, lives on through his art.