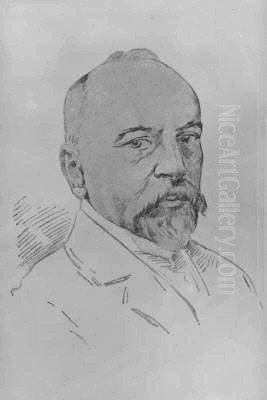

Isidor Kaufmann stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century European art, particularly renowned for his sensitive and detailed depictions of Jewish life in Eastern Europe. Born into a world undergoing rapid modernization and social change, Kaufmann dedicated his artistic career to capturing the traditions, rituals, and everyday moments of Jewish communities, particularly those adhering to Hasidic customs. His work serves not only as a valuable artistic achievement but also as a poignant historical record of a way of life that would soon be irrevocably altered. As an Austro-Hungarian Jewish painter working primarily in Vienna, Kaufmann navigated the complex cultural currents of his time, creating a unique niche that resonated with both Jewish and non-Jewish audiences, albeit for different reasons.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Isidor Kaufmann was born on March 22, 1853, in Arad, Hungary, which is now part of Romania. His parents were Hungarian Jews, and like many families of the time, they initially envisioned a more conventional path for their son. A career in commerce was planned for the young Isidor. However, his innate artistic inclinations proved too strong to ignore. Driven by a passion for painting, he made the decisive move to pursue art seriously.

In 1875, Kaufmann traveled to Budapest, the Hungarian capital, to begin his formal art training at the Landes-Zeichenschule (State Drawing School). This initial step confirmed his commitment to an artistic life. Seeking further refinement and exposure to a major European art center, he relocated to Vienna in 1876. There, he enrolled in the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). His studies placed him under the tutelage of Professor Josef Mathias von Trenkwald, a notable painter known for his historical subjects and large-scale frescoes, often associated with the late Nazarene movement and academic historicism. Studying under Trenkwald provided Kaufmann with a solid grounding in academic drawing, composition, and painting techniques, which would underpin his later detailed style.

Vienna: The Artistic Milieu

Vienna at the turn of the century was a crucible of cultural innovation and social tension. It was the capital of the sprawling Austro-Hungarian Empire, a city adorned with the monumental architecture of the Ringstrasse, reflecting imperial confidence and a taste for historicism. This was the Vienna of Emperor Franz Joseph I, but also the Vienna of burgeoning modernism. Figures like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele were challenging artistic conventions with the Vienna Secession, while Sigmund Freud was revolutionizing psychology, and Gustav Mahler was reshaping music.

Within this vibrant, complex environment, Vienna also hosted a large and increasingly assimilated Jewish population. Many Jewish families had achieved significant success in commerce, finance, and the professions, becoming prominent patrons of the arts and sciences. However, this period also witnessed the rise of modern political antisemitism, creating an undercurrent of unease beneath the glittering surface of Viennese society. Kaufmann, as a Jewish artist, operated within this dynamic. While his style remained largely rooted in academic realism, distinct from the avant-garde explorations of Klimt or Schiele, his subject matter – traditional Jewish life – held particular significance for a Jewish audience grappling with assimilation and identity, and offered an ethnographic glimpse for non-Jewish viewers. His meticulous approach echoed the detailed historicism popularised by earlier Viennese painters like Hans Makart, though applied to contemporary genre scenes rather than grand historical narratives.

The Journey East: Documenting Jewish Life

A defining aspect of Kaufmann's career was his dedicated effort to document the lives of Jews in the smaller towns (shtetls) and communities of Eastern Europe. Beginning in the 1890s, he undertook numerous journeys to regions such as Galicia (then part of Austria-Hungary, now divided between Poland and Ukraine), Poland, and Ukraine. These areas were home to large, traditional Jewish populations, many of whom followed Hasidic practices, maintaining distinct customs, modes of dress, and religious observances that differed significantly from the assimilated Jewish communities of Vienna or Budapest.

Kaufmann's travels were not mere tourist excursions; they were ethnographic expeditions fueled by a desire to capture the essence of this traditional world. He immersed himself in these communities, observing and sketching people, interiors, religious artifacts, and daily activities. He aimed to portray these scenes with authenticity and respect, capturing the piety, intellectual life, and communal bonds that characterized shtetl existence. His detailed studies and sketches made on these trips formed the basis for the meticulously finished oil paintings he would later complete in his Vienna studio. This dedication to firsthand observation lent his work a powerful sense of realism and intimacy.

Artistic Style and Technique

Isidor Kaufmann's artistic style is primarily characterized by a detailed, polished realism, deeply rooted in his academic training but applied with a unique sensitivity to his chosen subject matter. He worked predominantly in oil paint, often on wood panels, which allowed for a smooth, enamel-like finish that enhanced the clarity of detail. His brushwork is typically fine and controlled, leaving little trace of individual strokes and contributing to the overall sense of meticulousness.

His attention to detail is remarkable. Kaufmann painstakingly rendered the textures of fabrics – the velvet of a yarmulke, the sheen of a silk caftan, the rough weave of a prayer shawl. He meticulously depicted the interiors of synagogues and homes, capturing the patterns on wallpaper, the grain of wooden furniture, the gleam of brass candlesticks, and the intricate lettering in Hebrew books. This focus on the material culture surrounding his subjects adds depth and authenticity to his scenes. Comparisons can be drawn to the detailed genre scenes of 17th-century Dutch Golden Age painters like Johannes Vermeer or Gabriel Metsu, or to the minute precision of 19th-century academic realists such as the French painter Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier or the British classicist Lawrence Alma-Tadema, though Kaufmann's subject matter and emotional tone are distinctly his own.

Kaufmann was also a master of portraiture, capturing not just the physical likeness but also the perceived inner life and character of his subjects – the scholarly intensity of a Talmud student, the serene dignity of a rabbi, the quiet contemplation of an elderly woman. He often used warm, rich color palettes, particularly in his interior scenes, employing chiaroscuro (the contrast of light and shadow) to create a focused, intimate atmosphere. While fundamentally realistic, his work sometimes carries a subtle romantic or nostalgic quality, presenting Eastern European Jewish life with a sense of dignity, piety, and quiet grace.

Themes and Subjects

The core of Isidor Kaufmann's oeuvre revolves around the depiction of Jewish life, particularly within the traditional communities of Eastern Europe. His paintings explore various facets of this world, offering insights into religious practice, intellectual pursuits, and everyday existence. Common themes include scholars, often young men, deeply engrossed in the study of the Talmud or other sacred texts. These scenes emphasize the importance of learning and intellectual tradition within Judaism.

Portraits of rabbis and respected community elders are frequent, often depicted with a quiet dignity and spiritual authority. Family life and domestic scenes also feature prominently, showing moments like Sabbath preparations, quiet conversations, or interactions between generations. Kaufmann paid close attention to religious rituals and objects, depicting men wearing tefillin (phylacteries) for prayer, studying from Hebrew scrolls, or gathered in synagogues. The interiors themselves, whether humble homes or study houses (Beth Midrash), are rendered with such detail that they become characters in their own right, speaking volumes about the environment his subjects inhabited.

While his focus was often on male figures engaged in study or prayer, Kaufmann also painted sensitive portraits of women and children, capturing moments of domesticity and tradition. Works like Hannah portray traditional female figures, while others might depict family interactions. The overall mood in his paintings is typically one of quiet contemplation, piety, and studiousness, often imbued with a sense of warmth and intimacy, though sometimes tinged with a gentle melancholy or introspection, as seen in works like Der Zweifler (The Doubter).

Key Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of Isidor Kaufmann's style and thematic concerns:

Der Besuch des Rabbi (The Rabbi's Visit): This famous work, an original version of which was acquired by Emperor Franz Joseph I himself and is now housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, exemplifies Kaufmann's ability to capture moments of quiet dignity and respect within the community. It likely depicts a scene of consultation or blessing, rendered with his characteristic attention to detail in figures and setting.

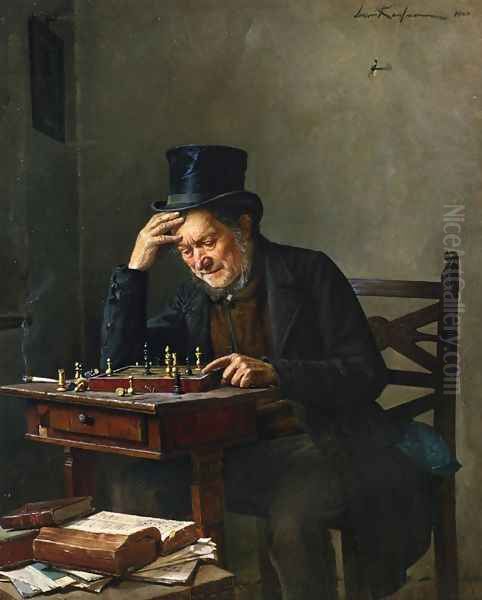

Schachspiel (Chess Players): Awarded a gold medal at a Vienna exhibition, this painting portrays a common pastime, yet imbues it with the contemplative atmosphere typical of Kaufmann's work. Chess, often seen as an intellectual pursuit, fits well within his broader theme of Jewish scholarly life, presented here in a moment of focused leisure.

Der Zweifler (The Doubter / The Skeptic): Also a gold medal winner in Vienna, this work is particularly intriguing. It typically depicts a young Talmudic scholar looking up from his books with a questioning or troubled expression, perhaps contemplating complex theological points or grappling with the challenges of faith in a changing world. It hints at the internal intellectual and spiritual life beyond simple piety.

Hannah: This painting, depicting a traditional Jewish woman, likely showcases Kaufmann's skill in female portraiture and his interest in capturing the specific attire and demeanor associated with traditional Jewish womanhood. It is held in the Charles and Lillian Schusterman Collection.

Young Rabbi from N. (1910): Housed in the Tate Images collection, this portrait exemplifies his focus on individual figures, likely capturing the likeness and character of a specific young religious leader encountered during his travels. The "N." might refer to a specific town he visited.

Cheerful Scholar: This work, executed in pencil, watercolor, and oil, suggests a lighter moment within the world of study, perhaps capturing the satisfaction of intellectual discovery.

Moses: An early work, likely reflecting his academic training while perhaps already hinting at his interest in foundational figures of Jewish history and faith.

Girl with a Hairflower: This painting, depicting a girl possibly wearing a bridal ornament made by her mother (perhaps related to the figure 'Hannah'), shows Kaufmann's interest in specific cultural artifacts and life cycle events.

The Gate of the Jewish Leader and Friday Evening in Brody (1904): These titles suggest works focusing on specific locations or moments in community life, further demonstrating his commitment to documenting the particularities of the places he visited, like the significant Jewish center of Brody in Galicia.

Patronage and Reception

Isidor Kaufmann achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His meticulous technique and appealing subject matter found favor with a diverse audience. Notably, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary acquired one of his most famous paintings, Der Besuch des Rabbi, signifying a high level of official recognition. This imperial patronage undoubtedly boosted his reputation.

Beyond royalty, Kaufmann found significant support among the affluent Jewish bourgeoisie in Vienna and other cities. For these often assimilated Jews, Kaufmann's paintings offered a connection to a heritage that might have felt increasingly distant. His works served as nostalgic reminders of tradition, piety, and the close-knit communities of their ancestors or relatives still living in Eastern Europe. They were seen as visual anchors to Jewish identity in a rapidly modernizing world. His paintings became desirable acquisitions, decorating the homes of prominent Jewish families.

His work was also well-received in official art circles. He exhibited regularly in Vienna and internationally, winning prestigious awards, including gold medals at the Vienna exhibition for Schachspiel and Der Zweifler, and recognition at the Munich International Exhibition. His paintings were acquired by major institutions, including the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and, later, collections like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This indicates that his work was appreciated not just for its subject matter but also for its artistic merit and technical skill, fitting within the accepted norms of late 19th-century realism.

The "Gute Stube" and Museum Work

Kaufmann's engagement with Jewish culture extended beyond easel painting. In a notable project in 1899, he collaborated with another artist, David Kohn, to create a unique installation for the newly established Jewish Museum in Vienna. This was the "Gute Stube" (Good Room), a three-dimensional, life-sized reconstruction of a traditional Jewish domestic interior from Eastern Europe.

This installation was pioneering for its time. It aimed to provide museum visitors with an immersive experience, transporting them into a typical Jewish home, complete with authentic furniture, textiles, religious objects, and everyday items that Kaufmann had likely observed or collected during his travels. The "Gute Stube" functioned as an early form of ethnographic display within an art and history museum context. It reflected Kaufmann's deep interest not just in depicting Jewish life on canvas but also in preserving and presenting its material culture. This project underscored his role as a cultural documentarian as well as an artist, contributing significantly to the early efforts of Jewish museology in Vienna.

Influence and Legacy

Isidor Kaufmann passed away in Vienna on December 16, 1921. His legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he perfected a style of detailed realism applied to a specific, culturally rich subject matter. His work stands apart from the major modernist movements of his time, yet holds its own distinct place in the history of European genre painting and portraiture.

His influence can be seen directly in the work of his students, most notably Lazar Krestin (1868-1938), who also specialized in depicting scenes of Eastern European Jewish life, carrying forward Kaufmann's thematic concerns and realistic style. More broadly, Kaufmann belongs to a significant group of Jewish artists active from the mid-19th to early 20th centuries who turned their attention to Jewish themes, seeking to represent their own culture and history. He can be situated alongside figures like the Polish painter Maurycy Gottlieb (1856-1879), who also depicted scenes from Jewish history and Polish Jewish life, and the German painter Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1799-1882), often considered the first major modern Jewish painter, known for his scenes of traditional German Jewish family life. While stylistically different, later artists like Marc Chagall (1887-1985), who drew heavily on his Eastern European Jewish roots, or German artists like Max Liebermann (1847-1935) who occasionally depicted Jewish subjects, or Jehudah Pen (1854-1937), Chagall's teacher in Vitebsk, also contributed to the visual representation of Jewish experience, though often with different artistic approaches.

Perhaps Kaufmann's most enduring legacy lies in the historical and cultural value of his work. His paintings serve as invaluable visual documents of the traditional Eastern European Jewish world – the shtetl culture – that was largely destroyed during the Holocaust. For subsequent generations, particularly descendants of European Jews, his works offer a tangible, evocative connection to a lost heritage. They are often described as "windows" onto a vanished past, preserving the faces, customs, and atmosphere of these communities with remarkable detail and empathy. His art continues to be studied by historians and appreciated by collectors and museum audiences worldwide, valued both for its artistic quality and its profound cultural significance as a record of Jewish life before the cataclysms of the 20th century.

Conclusion

Isidor Kaufmann carved a unique and enduring path in the art world of the late Austro-Hungarian Empire. Rooted in academic realism yet infused with deep personal engagement with his subject, he dedicated his considerable talents to chronicling the world of traditional Eastern European Jewry. Through meticulous detail, sensitive portraiture, and evocative scenes of study, prayer, and daily life, he created a body of work that is both artistically accomplished and historically invaluable. He navigated the cultural complexities of Vienna, finding patronage among emperors and assimilated Jewish families alike, while his journeys east allowed him to capture a vanishing way of life with authenticity and respect. Today, Kaufmann's paintings remain powerful testaments to a rich cultural heritage, offering poignant glimpses into the intimate world of the shtetl and securing his place as a vital painter of Jewish identity and history.