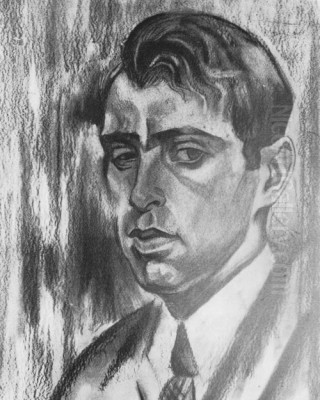

Issachar Ber Ryback stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 20th-century European art. Born into the vibrant, yet precarious, world of the Eastern European Jewish community, his life and work traversed the tumultuous terrains of revolution, pogrom, exile, and the burgeoning movements of modern art. A painter, graphic artist, and sculptor, Ryback dedicated much of his tragically short career to documenting and interpreting the life of the shtetl – the small Jewish towns and villages of Ukraine and Belarus – becoming a key participant in the Jewish cultural renaissance that flourished amidst the upheavals of his time. His art serves as both a poignant record of a world facing profound transformation and destruction, and a testament to the resilience of cultural identity expressed through the innovative languages of modernism. Identifying as a Jewish-Ukrainian-French artist, his journey took him from Kyiv to Moscow, Berlin, and finally Paris, reflecting the complex diasporic experience of many Jewish intellectuals and artists of his generation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Kyiv

Issachar Ber Ryback was born in 1897 in Yelisavetgrad (now Kropyvnytskyi), Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. This region was a heartland of Jewish life, and the cultural milieu of his upbringing would profoundly shape his artistic vision. He pursued formal art training at the Kyiv Art School, studying there from approximately 1911 to 1916. This period was crucial for his development, exposing him to the crosscurrents of artistic innovation sweeping across Europe.

In Kyiv, Ryback studied under influential artists such as Alexander Bogomazov, a key figure in Ukrainian Futurism, and Alexandra Exter, a prominent avant-garde painter and designer with connections to both Russian and Parisian modernism. These mentors introduced him to the principles of Cubism and Futurism, styles that emphasized fragmented forms, dynamic movement, and a departure from traditional representation. Ryback absorbed these influences, experimenting with geometric abstraction and bold compositions in his early work.

Beyond his formal training, Ryback was deeply engaged with the burgeoning Yiddish cultural movement in Kyiv. He was influenced by leading Yiddish writers like David Bergelson and David Hofstein, who sought to create a modern Jewish literature rooted in contemporary experience. This intellectual environment fostered Ryback's commitment to exploring Jewish themes through a modern artistic lens. An early example of his work from this period, the oil painting City/Village (1917), now held in the National Art Museum of Ukraine (NAMU), likely reflects this nascent synthesis of avant-garde style and local subject matter.

Revolution, Trauma, and the Shtetl's Elegy

The years following Ryback's studies were marked by immense political and social turmoil: the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the subsequent civil war, which brought devastating violence to Ukraine, including waves of antisemitic pogroms. This period inflicted deep personal tragedy upon Ryback. His hometown suffered destruction, and in 1919, his father was murdered during a pogrom. This traumatic event became a defining moment, solidifying his resolve to document the fate of his people and the vanishing world of the shtetl.

In response to the violence and destruction he witnessed, Ryback embarked on a project that would become one of his most significant contributions: a series of lithographs depicting the ravaged landscapes and uprooted lives of Ukrainian Jewry. This culminated in the portfolio Shtetl, Mayn Khorever Haym – A Gekhotemt (My Destroyed Home: A Remembrance), published in Berlin in 1923 by Schwellen Verlag, though conceived earlier around 1917. This powerful series stands as a harrowing visual testimony to the pogroms and the disintegration of traditional Jewish life.

The lithographs in My Destroyed Home blend Cubo-Futurist fragmentation with Expressionist intensity. Figures are often distorted, angular, and imbued with a profound sense of grief and displacement. Buildings lean precariously, streets are empty or filled with mourning figures, and traditional symbols of Jewish life appear broken or overshadowed by violence. Ryback does not merely document; he interprets the emotional and psychological impact of the trauma, creating an elegy for a lost world. This work established him as a vital artistic voice chronicling the Jewish experience during this catastrophic period.

The Berlin Years: Avant-Garde Engagement

Around 1921, likely fleeing the ongoing violence and instability in Ukraine, Ryback moved to Berlin. The city, then the vibrant capital of the Weimar Republic, was a major center for artistic experimentation and a refuge for many artists and intellectuals escaping turmoil in Eastern Europe. Ryback quickly integrated into the city's dynamic art scene. He became an active member of the Novembergruppe (November Group), a radical association of artists and architects committed to linking art with social revolution and rebuilding society after the war.

His involvement with the Novembergruppe placed him alongside prominent figures of the German avant-garde, although specific interactions are not detailed in the provided sources. During his Berlin period, Ryback participated in several important exhibitions, including uncensored shows of Jewish art, reflecting a growing assertion of Jewish cultural identity within the modernist movement. He also designed logos for Jewish educational organizations, further demonstrating his commitment to community life.

Berlin was also a hub for the international Jewish avant-garde. Ryback collaborated closely with El Lissitzky, another towering figure of Russian-Jewish modernism. Together, they worked on projects aimed at creating memorial art for the Jewish communities devastated by pogroms in Ukraine and Belarus. They were both involved with the Kultur-Lige (Culture League), an organization founded in Kyiv dedicated to fostering modern Yiddish culture, including art, literature, and education. Ryback and Lissitzky participated in ethnographic expeditions, documenting traditional Jewish art forms like synagogue paintings and gravestone carvings, seeking to integrate these folk traditions into a contemporary artistic language.

Ryback's discussions with fellow artists like the Polish-Jewish painter Henryk Berlewi during this time delved into the fundamental questions of Jewish art. They debated the nature of a distinctly Jewish artistic expression and explored the potential of abstraction versus figuration in conveying Jewish themes and experiences. This period marked a phase of intense artistic and intellectual activity for Ryback, solidifying his position within the European avant-garde while deepening his focus on Jewish subject matter.

Moscow Interlude and Theatrical Design

In 1925, Ryback spent a period working in Moscow. The Soviet Union, in its early years, still offered opportunities for avant-garde artists, particularly in fields like graphic design and theater. Ryback contributed his talents to the burgeoning Soviet Yiddish theater scene, designing stage sets. This work connected him with other artists involved in theatrical innovation, such as Marc Chagall (who had earlier worked with the Moscow State Jewish Theater) and potentially figures like Nathan Altman and Robert Falk, who were also active in Jewish cultural circles and theater design.

Designing for the stage allowed Ryback to explore spatial dynamics and narrative expression in a different medium. His experience likely involved translating the visual language he developed in his paintings and prints into three-dimensional environments, creating evocative settings for Yiddish plays that often dealt with themes of tradition, modernity, and social change within Jewish life. This brief Moscow interlude highlights the breadth of his artistic engagement and his connections across different centers of Jewish cultural activity.

The Paris Years: Maturity and Continued Focus

In 1926, Ryback made his final significant move, relocating to Paris. Paris was then the undisputed capital of the international art world, home to the diverse and cosmopolitan École de Paris (School of Paris). Many Jewish artists from Eastern Europe had converged there, including figures like Chaim Soutine and Amedeo Modigliani (though Modigliani had died in 1920). Ryback became part of this vibrant milieu, continuing his artistic practice within a new context.

During his Paris years, Ryback's style reportedly evolved towards a more realistic, though still expressive, manner. Some sources suggest a shift towards more delicate depictions of Jewish life, perhaps reflecting a different environment or a maturation of his artistic vision away from the raw trauma depicted in his earlier works. He continued to exhibit his work, holding solo shows at galleries such as the Galerie aux Quatre Chemins and Galerie L'Anticain.

In 1926, while in Paris, he published the album On the Jewish Fields of the Ukraine. This work, likely stemming from the earlier ethnographic expeditions with Lissitzky, combined Ryback's drawings and possibly photographs, offering a visual record of rural Jewish life, its customs, characters, and material culture. It represented a continuation of his mission to document and interpret the world of the shtetl, albeit perhaps with a more ethnographic or nostalgic lens compared to the starkness of My Destroyed Home.

Despite his activity, some accounts suggest that Ryback did not achieve the same level of recognition or integration into the mainstream Paris art scene as he had in Berlin. This might have been due to prevailing artistic tastes in Paris, which perhaps favored different styles, or the sheer density of artistic talent competing for attention. Nevertheless, he remained a dedicated artist, continuing to explore his core themes until his untimely death.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Mediums

Issachar Ber Ryback's artistic style is characterized by its dynamic synthesis of major European avant-garde movements and a deep engagement with Jewish folk traditions and contemporary Jewish life. His early work clearly shows the impact of Cubism and Futurism, evident in the fragmented forms, geometric structures, and sense of dynamism found in paintings like City/Village. He adapted these formal innovations to serve his thematic concerns.

The central theme throughout Ryback's oeuvre is the Jewish shtetl – its people, traditions, landscapes, and its fate in the modern era. He depicted synagogues, marketplaces, craftsmen, scholars, families, and religious rituals. His work captures both the vibrancy and the vulnerability of this world. Following the pogroms, themes of destruction, loss, mourning, and memory became prominent, particularly in his graphic work. His art often reflects the tension between tradition and modernity, continuity and rupture.

Ryback worked across various mediums. He was a proficient painter, but perhaps his most impactful and widely recognized works are his lithographs, particularly the My Destroyed Home series. He was also a skilled illustrator, contributing significantly to Yiddish children's books, where his style often combined modernist simplification with folk-art charm. His involvement in ethnographic expeditions suggests an interest in documentation, possibly including photography, and his work for the theater demonstrates his ability to work spatially and collaboratively.

His use of color was often bold and expressive, contributing to the emotional intensity of his work. Even when his style shifted towards greater realism in his later Paris years, his focus remained steadfastly on Jewish subjects, exploring identity, community, and history through a distinctly modern, yet deeply personal, artistic language. He drew inspiration not only from visual art movements but also from modern Yiddish literature and the visual heritage of Jewish folk art.

Connections and Contemporaries

Ryback's career placed him in contact with a wide network of influential artists, writers, and cultural figures across Europe. His formative years in Kyiv connected him with Alexander Bogomazov and Alexandra Exter. His engagement with Yiddish culture brought him into the orbit of writers David Bergelson and David Hofstein.

In Berlin and during his involvement with the Jewish avant-garde, his most significant collaborator was El Lissitzky. He was part of a broader movement that included artists like Nathan Altman, Marc Chagall, and Robert Falk, all exploring modernism through a Jewish lens. His discussions with Henryk Berlewi highlight the intellectual debates surrounding Jewish art at the time. As a member of the Novembergruppe, he was part of the German Expressionist and avant-garde scene.

His time in Paris situated him within the École de Paris, a melting pot of international artists, many of them Jewish emigres like Chaim Soutine. While direct interactions with all these figures might not be documented, Ryback operated within these interconnected circles. His work shares thematic concerns with Chagall's depictions of shtetl life, though Ryback's style is often starker and less fantastical. Other contemporaries involved in Jewish theater design included Boris Aronson. This network underscores Ryback's position within a transnational movement seeking to define modern Jewish culture.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Issachar Ber Ryback died tragically young from tuberculosis in Paris in 1935, cutting short a career of significant achievement and promise. Despite his relatively brief working life, he is recognized as a central figure in the Russian Jewish Modernist movement and the broader Jewish cultural renaissance of the early 20th century. He stands alongside figures like Chagall, Lissitzky, Altman, and Berlewi as an artist who successfully forged a modern artistic language deeply rooted in Jewish experience.

His primary legacy lies in his powerful and poignant depictions of the Eastern European shtetl, particularly his visual testimony to the destruction wrought by the pogroms. Works like My Destroyed Home are invaluable not only for their artistic merit – their expressive power and innovative style – but also as historical documents capturing a critical and traumatic moment in Jewish history. His contributions to Yiddish book illustration and theater design further highlight his commitment to the vitality of modern Jewish culture.

While perhaps not as universally famous as Chagall, Ryback's work has received renewed attention and appreciation. Exhibitions, such as the one held at the Bat Yam Museum of Art in Israel (2022-2023), continue to explore his oeuvre and affirm his importance. His art is held in collections including the National Art Museum of Ukraine and the Israel Museum, among others. He is remembered as an artist who navigated the complex intersections of tradition and modernity, trauma and resilience, using the tools of the avant-garde to give voice to the specific experiences of his people while contributing to the broader currents of European modern art. His work remains a vital resource for understanding both Jewish history and the diverse trajectories of 20th-century modernism.