Wilhelm Wachtel stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century European art. A Polish-Jewish artist, his life and work offer a poignant lens through which to view the cultural, social, and political currents that shaped the Jewish experience in Eastern Europe during a period of profound transformation and turmoil. His art, predominantly rooted in Realism but touched by later currents, dedicated itself to the depiction of Jewish life, traditions, and the burgeoning Zionist consciousness, making him an important visual chronicler of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in a Shifting World

Wilhelm Wachtel was born in 1875 in Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine), a vibrant multicultural city within the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia. At the time, Lwów was a major center of Polish and Jewish culture, fostering a dynamic intellectual and artistic environment despite the complexities of existing under imperial rule. This setting undoubtedly played a crucial role in shaping Wachtel's worldview and artistic inclinations. His Polish nationality was a matter of the political reality of the time, with Lwów being a key Polish cultural hub, while his Jewish heritage would become a central pillar of his artistic expression.

His formal artistic training began at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, where he studied from 1895 to 1899. Kraków, another historic Polish city, was then a crucible of artistic innovation, particularly with the rise of the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement. This movement, which encompassed literature, visual arts, and music, sought to create a modern Polish national art, often drawing on symbolism, Art Nouveau, and folk traditions. Artists like Jacek Malczewski, Stanisław Wyspiański, and Józef Mehoffer were leading figures, and their influence, along with the legacy of historical painters like Jan Matejko (though Matejko passed in 1893, his impact was still profound), created a rich artistic atmosphere.

Following his studies in Kraków, Wachtel further honed his skills at the Nikolai Giska Academy in Warsaw. Warsaw, then under Russian imperial control, also had a thriving, albeit distinct, artistic scene. The exposure to different artistic pedagogies and environments in these two major Polish centers provided Wachtel with a solid foundation in academic techniques while also exposing him to contemporary European art trends.

Thematic Focus: Jewish Life, Identity, and Realism

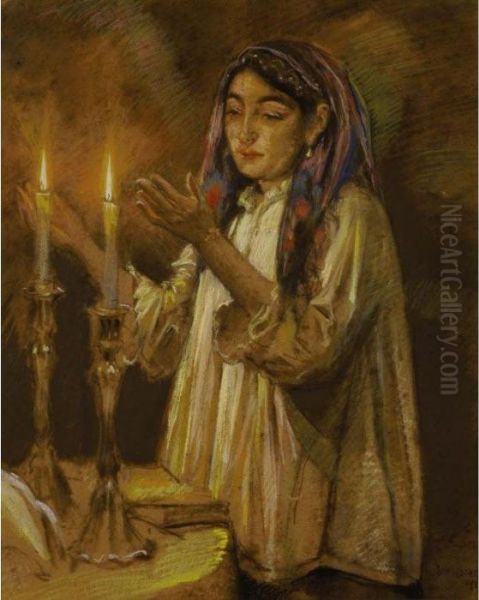

Wachtel’s primary artistic commitment was to the visual representation of Jewish culture and identity. His work often delved into the everyday lives, religious practices, and communal experiences of Jewish people, particularly those in Galicia. This focus was not merely ethnographic; it was imbued with a deep empathy and a desire to convey the humanity and dignity of his subjects, often in the face of rising antisemitism and societal pressures.

A significant platform for Wachtel’s early work was the Rocznik Żydowski (Jewish Yearbook), for which he provided illustrations. These images were powerful visual statements that sought to portray Jewish life with nuance and strength, consciously avoiding one-dimensional stereotypes that were prevalent at the time. His approach was largely rooted in Realism, a style that emphasized accurate depiction and often carried social or political undertones. This allowed him to capture the textures of Jewish existence – the solemnity of study, the warmth of community, and the undercurrent of hardship.

His Realism was not static; it evolved. While early works might show the darker, more somber palette characteristic of some 19th-century academic painting and perhaps even echoes of the Barbizon School's moodiness (artists like Jean-François Millet or Camille Corot championed rural realism), Wachtel's style later showed an absorption of Impressionistic aesthetics. This is evident in a lighter palette, a greater concern for the effects of light, and a more broken brushwork in some of his later pieces, particularly landscapes.

Key Works: Narratives of Sorrow, Resilience, and Hope

Several of Wilhelm Wachtel's works stand out for their thematic depth and artistic execution, reflecting the spectrum of Jewish experience he sought to portray.

One of his most impactful pieces is After the Pogrom (also known by its Polish title, Po pogromie, and sometimes referred to in connection with a 1906 work, Christ after the Pogrom). This painting, or series of works on the theme, directly confronted the brutal reality of anti-Jewish violence that plagued Eastern Europe. Wachtel’s depiction often focused on the aftermath, particularly the grief and desolation of the victims, with a notable emphasis on the sorrow of women. These works were not just reportage; they were powerful indictments of persecution and expressions of profound empathy. The raw emotion conveyed through a realistic, yet deeply felt, style made such pieces resonate strongly within Jewish communities and among socially conscious viewers.

Another work, titled Kiszeniew, almost certainly refers to the infamous Kishinev pogrom of 1903, an event that sent shockwaves across the Jewish world and galvanized international opinion. By tackling such a sensitive and tragic subject, Wachtel aligned himself with artists who used their craft as a form of social commentary and historical testimony.

Beyond the depictions of tragedy, Wachtel also created more intimate portrayals of Jewish life. His painting Galician Hasidic Boy (1905) is an example of his engagement with specific cultural milieus within Judaism. Such genre scenes offered glimpses into the traditions and character of Galician Jewry, capturing a world that was rapidly changing.

His later involvement with Zionist ideals is reflected in his illustrations for the Land of Israel magazine. These works would have expressed a sense of hope and aspiration for a Jewish homeland, contrasting with the themes of suffering found in his pogrom-related art. This thematic duality – acknowledging hardship while also looking towards a future of self-determination – is characteristic of much Jewish art of this period.

A piece titled Silwan, which was auctioned in 2013, suggests his travels and work in Palestine, as Silwan is an ancient neighborhood in Jerusalem. This further underscores his connection to the land of Israel and the Zionist movement, which was gaining momentum among European Jews in the early 20th century.

Wachtel and His Contemporaries: A Shared Artistic Milieu

Wilhelm Wachtel was part of a vibrant generation of Polish-Jewish artists who grappled with similar themes of identity, tradition, and modernity. His interactions, influences, and perhaps even friendly rivalries with these contemporaries are crucial to understanding his place in art history.

Among the most prominent were Samuel Hirszenberg (1865-1908), Leopold Pilichowski (1869-1934), and Isidor Kaufmann (1853-1921). These artists, like Wachtel, dedicated much of their oeuvre to Jewish subjects.

Samuel Hirszenberg, born in Łódź, was known for his large-scale, often somber, depictions of Jewish life and suffering, such as The Wandering Jew, Exile, and The Black Banner (mourning a pogrom). There is evidence that Hirszenberg was inspired by the "passion themes" explored by both Wachtel and Pilichowski. Indeed, Wachtel and Hirszenberg are noted to have collaborated on works themed around "Lamentation and Pietà," indicating a close artistic dialogue. Wachtel's Christ after the Pogrom (1906) is also linked to Hirszenberg, suggesting shared thematic concerns or direct artistic exchange. Hirszenberg, in turn, was considered by some to be the most important Polish-Jewish painter after the tragically short-lived Maurycy Gottlieb (1856-1879), whose poignant historical and biblical scenes had set a high bar for Jewish national art.

Leopold Pilichowski, also from Poland, similarly focused on Jewish genre scenes, portraits, and depictions of historical events, including works like Pietà/Darkness (1910) and Po pogromie (After the Pogrom), echoing Wachtel's thematic concerns.

Isidor Kaufmann, though born in Hungary and active mainly in Vienna, frequently traveled to Galicia and other parts of Eastern Europe to paint scenes of traditional Jewish life. His meticulously detailed and often sentimental portrayals of rabbis, scholars, and everyday folk were highly popular. Hirszenberg's early style is sometimes compared to Kaufmann's, highlighting a shared interest in ethnographic representation.

These artists, including Wachtel, often navigated a complex artistic landscape. While their work was vital for Jewish cultural expression, it sometimes faced misunderstanding or marginalization within broader national art circles that were more focused on other definitions of national identity. Nevertheless, they were instrumental in establishing a distinctively "Jewish art," creating a visual language that resonated with their communities and documented a way of life. They participated in exhibitions in Lwów and other centers, often supported by Jewish patrons and intellectuals who recognized the importance of their work.

Beyond this immediate circle of Jewish artists, Wachtel's education in Kraków would have exposed him to the broader currents of Polish art. The Young Poland movement, with figures like Stanisław Wyspiański, who was a multifaceted artist exploring Polish history, folklore, and modernist aesthetics, and Jacek Malczewski, known for his symbolic and patriotic paintings, created a dynamic environment. While Wachtel’s primary focus remained on Jewish themes, the artistic ferment of Kraków undoubtedly contributed to his development. Other Polish artists of the period, such as Józef Chełmoński, known for his Polish landscapes and genre scenes, or Aleksander Gierymski, a realist and precursor of Polish impressionism who also depicted Jewish life in Warsaw, formed part of the wider artistic context.

Artistic Circles and Geographic Movements: Vienna, Paris, Palestine

Wachtel's career was not confined to Poland. He lived and worked in Vienna, Paris, and Palestine, each location offering new influences and opportunities.

Vienna, as the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was a major cultural hub. For an artist from Lwów, Vienna would have been a natural destination for artistic exposure and career advancement. The Viennese Secession, led by artists like Gustav Klimt, was challenging artistic conventions, though Wachtel's style remained more aligned with Realism.

Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world in the early 20th century, attracted artists from across the globe. Here, Wachtel would have encountered a dazzling array of artistic movements, from Post-Impressionism to Fauvism and Cubism. While it's not clear how deeply these avant-garde movements affected his core style, the experience of Paris would have broadened his artistic horizons. He would have been among a cohort of Eastern European Jewish artists, like Marc Chagall (though Chagall's major Parisian period was slightly later), Chana Orloff, and Amedeo Modigliani (an Italian Jew), who flocked to Paris.

His time in Palestine is particularly significant. This period aligns with his growing interest in Zionism and the desire to depict the nascent Jewish life in the ancestral homeland. His illustrations for the Land of Israel magazine and works like Silwan attest to this engagement. In Palestine, he would have encountered the early stirrings of the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, founded in Jerusalem in 1906 by Boris Schatz, which aimed to create a new Jewish national art style blending European techniques with Middle Eastern and biblical motifs. Artists like Reuven Rubin and Nahum Gutman would later become key figures in Israeli art, building on this foundation.

Wachtel also spent time in the United States, notably in Los Angeles, where he exhibited his work and became a recognized figure in the local art scene. This transcontinental career reflects the diasporic nature of Jewish life and the search for new centers of cultural expression.

Legacy, Collections, and Auction Records

Wilhelm Wachtel's works are found in various collections, and they occasionally appear at auction, providing glimpses into his market presence.

A significant institutional holding is the portrait of Maurycy Lazarus (1903) housed in the Borys Voznytsky National Art Gallery in Lviv, his city of birth. This indicates his recognition within his local artistic community.

Auction records provide further evidence of his work's circulation. For instance, his painting Silwan was sold at "Auction 29" in 2013 for an estimated $2,000-$2,500. Another piece, a work measuring 49 x 33 cm, was reportedly sold at a higher price in an auction in Haifa (though some sources suggest a Sotheby's Tel Aviv auction in October 2000). While specific details about every auction are not always readily available, these instances show that his work continues to be valued by collectors, particularly those interested in Judaica and early 20th-century Eastern European art.

It is important to distinguish Wilhelm Wachtel the Polish-Jewish artist from Elmer Wachtel (1864-1929), an American painter known for his Californian Impressionist landscapes. Collections holding Elmer Wachtel's works, such as the Santa Barbara Museum of Art or the Fleischer Museum, are sometimes mistakenly associated with Wilhelm Wachtel due to the similar surname. This distinction is crucial for accurate art historical attribution.

Unresolved Aspects and Scholarly Discussion

Like many artists from periods of significant historical upheaval, certain aspects of Wilhelm Wachtel's life and work remain subjects for further research and discussion.

One minor but persistent point is the variation in the spelling of his name. Some historical records or references might use alternative spellings, such as "Wachtelikul," which could reflect transliteration issues or regional linguistic variations. While seemingly trivial, such discrepancies can sometimes complicate archival research.

More substantially, the interpretation of his works, particularly those dealing with religious and cultural themes, continues to be an area of art historical interest. His paintings, such as After the Pogrom, carry complex layers of meaning. They are at once depictions of historical events, expressions of communal grief, critiques of antisemitism, and affirmations of Jewish resilience. The use of Christian iconographic parallels in some Jewish art of the period (for instance, the "Pietà" theme mentioned in connection with Wachtel and Hirszenberg, or Wachtel's Christ after the Pogrom) is a fascinating area of study, reflecting attempts to communicate Jewish suffering to a wider, often Christian-majority, audience using familiar visual language, or to express universal themes of martyrdom and sorrow.

The provided information also contained references to a Wilhelm Wachtel involved in mustard gas research during World War I and another Wilhelm Wachtel associated with the "January Effect" in the stock market. It is critically important to state that these almost certainly refer to different individuals. Conflating the artist Wilhelm Wachtel with figures from entirely different fields would be a significant error. The focus for the art historian remains on Wilhelm Wachtel the painter, his artistic output, and his cultural context.

Conclusion: A Voice for a People

Wilhelm Wachtel passed away in 1942, a year that falls tragically within the darkest period of the Holocaust. His death marked the end of a career dedicated to giving visual form to the Jewish experience in Eastern Europe. Through his realistic portrayals of daily life, his poignant responses to persecution, and his hopeful depictions related to the Zionist dream, Wachtel created a body of work that serves as both an artistic achievement and an invaluable historical document.

He was part of a generation of artists who saw art not just as an aesthetic pursuit but as a vital means of cultural affirmation and communication. Alongside contemporaries like Samuel Hirszenberg, Leopold Pilichowski, and Isidor Kaufmann, and within the broader artistic currents of Poland and Europe that included figures from Jan Matejko to the Impressionists, Wachtel carved out a unique niche. His paintings and illustrations offer a window into a world that was vibrant, complex, and ultimately, tragically transformed. His legacy lies in the enduring power of his images to convey the humanity, struggles, and aspirations of the Polish-Jewish community in the early 20th century.