Cassius Marcellus Coolidge, an American artist whose name might not immediately resonate with the frequency of Renaissance masters or Impressionist icons, nonetheless carved an indelible niche in the annals of popular culture. Born on September 18, 1844, in Antwerp, New York, and passing on January 13, 1934, in New York City, Coolidge is the creative force behind one of the most recognizable and parodied series of paintings in American art: "Dogs Playing Poker." While often categorized as kitsch or purely commercial art, a deeper examination reveals an artist with a keen sense of humor, an astute understanding of his audience, and a surprisingly diverse, albeit unconventional, path to artistic renown. His works, particularly the anthropomorphic canines engaged in very human pastimes, have transc Bahkan (even) transcended their original advertising intent to become iconic images, reflecting and satirizing aspects of American middle-class life and aspirations.

Early Life and a Self-Taught Path

Coolidge, affectionately known as "Cash" by friends and family – a nickname he would later playfully incorporate into his signature – grew up in a modest environment. Unlike many of his contemporaries who sought formal artistic training in the academies of Europe or established institutions in America, Coolidge was largely self-taught. His early years were spent in Philadelphia before his family returned to upstate New York. This lack of formal academic art education meant he was unburdened by the strictures and conventions of the traditional art world, allowing a more idiosyncratic and commercially-minded approach to flourish. His artistic inclinations likely manifested early, but his path to becoming a full-time artist was circuitous, marked by a variety of entrepreneurial and professional endeavors. This practical, real-world experience would, in many ways, inform the accessible and relatable nature of his most famous works.

A Man of Many Hats: Coolidge's Diverse Careers

Before dedicating himself to art, Cassius Coolidge explored a remarkable array of professions, showcasing a restless energy and an entrepreneurial spirit. Between 1868 and 1872, he worked as a druggist, a common and respected profession of the era. He also tried his hand at sign painting, an endeavor that would have provided practical experience in composition, lettering, and the use of color for immediate visual impact – skills that would later serve him well in his commercial art.

His ambitions extended beyond these roles. In the early 1870s, Coolidge demonstrated significant local initiative by founding the first bank in his hometown of Antwerp, New York. Concurrently, he also established a local newspaper. These ventures, while perhaps not achieving long-term monumental success, underscore his drive and his engagement with the fabric of community life. He was also, at various points, a teacher, a town mayor (though details on this are less prominent), and a general small business owner. This eclectic resume paints a picture of a man unafraid to try new things, a pragmatist who understood commerce and community – perspectives that subtly permeate his later artistic output, which often depicted scenes of leisure and social interaction common to the American middle class he knew so well.

The Dawn of an Artistic Career: Cartoons and Comic Foregrounds

Coolidge's artistic journey began in earnest in his twenties when he started creating humorous drawings and cartoons for local newspapers. This was a popular medium at the time, offering social commentary and entertainment to a wide audience. His knack for caricature and humorous observation found an early outlet here.

A particularly inventive and commercially successful creation from this period was his development of "comic foregrounds." These were life-sized painted cutouts, often depicting amusing or aspirational figures (a bodybuilder, a hula dancer, a person in an outlandish costume), with the head area removed. People could then stand behind the cutout, placing their own head in the space, and have a photograph taken. These novelties became immensely popular at carnivals, fairs, and seaside resorts, offering a playful form of personalized entertainment. Coolidge even received a patent for these "photographic foregrounds," demonstrating his business acumen alongside his artistic creativity. This early success in creating widely appealing, humorous imagery for a commercial market was a clear precursor to his later achievements.

The Commission That Defined a Legacy: Brown & Bigelow

The pivotal moment in Coolidge's artistic career arrived in 1903. The St. Paul, Minnesota-based advertising firm Brown & Bigelow, a major producer of calendars, promotional items, and playing cards, approached him with a commission. They sought a series of oil paintings to be used for advertising a brand of cigars. Coolidge was tasked with creating sixteen paintings, the majority of which would feature anthropomorphic dogs engaged in various human activities.

Out of this commission, nine paintings specifically depicted dogs playing poker. These were not his first foray into painting dogs in human-like situations, as an earlier 1894 painting titled Poker Game already showcased this theme. However, the Brown & Bigelow series solidified this as his signature subject. These images were reproduced on calendars, posters, and other advertising materials, disseminating them far and wide across America. The cigars they were meant to advertise have long since faded into obscurity, but Coolidge's poker-playing dogs embarked on a journey into the heart of American popular iconography.

"Dogs Playing Poker": An In-Depth Look

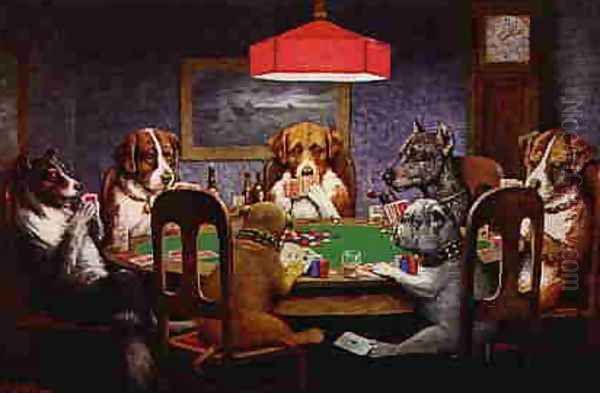

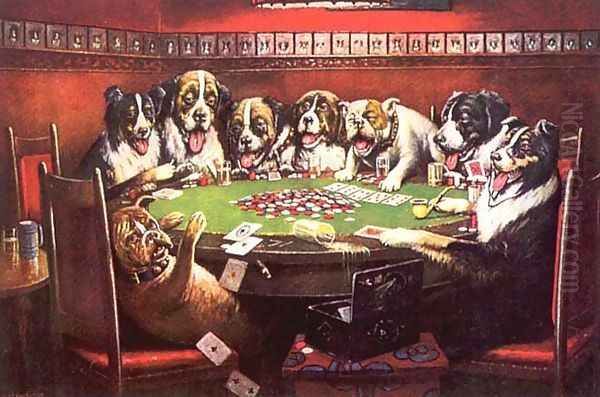

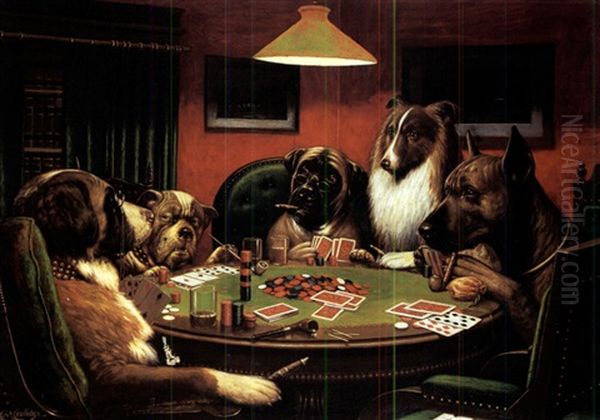

The "Dogs Playing Poker" series is not a single artwork but a collection of scenes, each with its own narrative and cast of canine characters. These paintings are characterized by their meticulous detail, the expressive (if somewhat caricatured) faces of the dogs, and the humorous juxtaposition of animal figures with sophisticated, and sometimes seedy, human behaviors.

Among the most famous titles from this series are:

A Friend in Need (circa 1903): Perhaps the most iconic image, it depicts a tense poker game where one bulldog slyly passes an ace to his bulldog companion under the table, hidden from the other players (often depicted as various other breeds like St. Bernards, Great Danes, and collies). The humor lies in the blatant cheating and the very human expressions of concentration, anxiety, and cunning on the dogs' faces.

A Bold Bluff (circa 1909) and Waterloo (circa 1909): These two paintings are often considered a pair. A Bold Bluff shows a St. Bernard confidently betting a large pile of chips, holding a very weak hand (a pair of deuces, perhaps), while his opponents eye him suspiciously. Waterloo depicts the aftermath, with the St. Bernard raking in a massive pot, his bluff having succeeded, much to the dismay of the other players. The narrative arc across these two pieces showcases Coolidge's storytelling ability.

His Station and Four Aces (circa 1903): This painting shows a group of dogs on a train, engrossed in a poker game. The title itself is a pun, referring both to a train station and a powerful poker hand.

Pinched with Four Aces (circa 1903): Here, the game takes a dramatic turn as police dogs raid the poker game, catching the players (presumably with ill-gotten gains or in an illegal gambling den) in the act. This adds a layer of playful criminality to the canine world.

Poker Sympathy (circa 1903): This image shows a more somber side of the game, with one dog looking dejected after a loss, perhaps being consoled by another, while the winner looks on.

Post Mortem (circa 1903): The dogs gather after a game, perhaps discussing the hands played or settling debts, with empty glasses and overflowing ashtrays hinting at a long night.

Other paintings in the broader Brown & Bigelow commission included dogs in other human scenarios, such as A Breach of Promise Suit, New Year's Eve in Dogville, and Riding the Goat, showcasing Coolidge's versatility within the anthropomorphic theme. The dogs are typically depicted in dimly lit, smoky rooms, often around a circular table, with accessories like whiskey glasses, cigars, and pipes, all contributing to a distinctly masculine, early 20th-century leisure environment.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Influences

Coolidge's style is characterized by a competent, if not revolutionary, realism in rendering the dogs and their environments, combined with a highly imaginative and humorous conceptual approach. His lighting often emulates the chiaroscuro effect, with focused light sources (like an overhead lamp) illuminating the central action, reminiscent, in a very distant and popularized way, of artists like Caravaggio or Georges de La Tour, who were masters of dramatic, intimate, candlelit scenes. While Coolidge's work lacks their profound spiritual or psychological depth, the visual strategy of highlighting a central, engaging scene in a darker setting shares a superficial similarity.

The themes explored in his "Dogs Playing Poker" series are multifaceted. On the surface, they are humorous depictions of animals acting like humans. However, they also tap into aspects of the human condition: camaraderie, competition, deception, risk-taking, and the social rituals of games of chance. The dogs, with their varied breeds often humorously suggesting different human archetypes (the sly bulldog, the imposing St. Bernard, the thoughtful collie), act as stand-ins for middle-class men of the era, engaging in activities that were common in male social circles.

While Coolidge was self-taught, it's plausible he was aware of a broader tradition of anthropomorphic art. The 19th century saw artists like Sir Edwin Landseer in England, who painted animals with remarkable skill and often imbued them with human-like sentiments and narrative roles (e.g., The Old Shepherd's Chief Mourner or Dignity and Impudence). Landseer's work was immensely popular and widely reproduced. Another significant figure in this vein was the French caricaturist J.J. Grandville, whose satirical illustrations often featured animals dressed in human clothes and engaging in human activities to comment on society and politics.

It is also important to note that Coolidge was not the absolute first to depict dogs playing cards. The English artist Philip Reinagle painted a series of works in the early 19th century titled A Humorous Scene of Dogs Playing Cards, which predate Coolidge by several decades. Whether Coolidge was directly aware of Reinagle's work is uncertain, but the theme was not entirely novel. However, Coolidge's particular execution, his narrative flair, and the sheer ubiquity achieved through Brown & Bigelow's reproductions made his version the definitive one in the public imagination.

The influence of earlier genre painters, such as the Dutch Golden Age masters like Jan Steen or Adriaen Brouwer, who depicted lively, often boisterous scenes of everyday life, taverns, and games, might also be considered as part of a broader artistic context. These artists captured human interactions and foibles with keen observation, a quality Coolidge, in his own way, applied to his canine subjects. Even the satirical narratives of William Hogarth, with his "modern moral subjects" like A Rake's Progress, share a distant kinship in their storytelling and social commentary, albeit with a far more serious and critical edge than Coolidge's generally lighthearted approach.

The mention of Paul Cézanne or Eugène Delacroix as influences, as sometimes suggested, seems more tenuous for Coolidge's specific style. Cézanne's revolutionary approach to form and space, and Delacroix's dramatic Romanticism, operate in a different artistic universe than Coolidge's accessible, commercial illustrations. However, if one considers a broad appreciation for strong composition (Delacroix) or the depiction of solid forms (Cézanne), perhaps a very indirect line could be drawn, but direct stylistic influence is unlikely. Coolidge's primary "influences" were more likely the popular visual culture of his time, the demands of commercial illustration, and his own innate sense of humor.

Kitsch or Americana? Critical Reception and Popular Appeal

During his lifetime and for many decades after, Cassius Marcellus Coolidge's work, particularly "Dogs Playing Poker," was largely dismissed by the serious art world. It was often labeled as "kitsch" – art considered to be in poor taste because of its garishness or sentimentality, but appreciated in an ironic or knowing way. The commercial origins of the paintings, their mass reproduction, and their unabashedly popular appeal placed them outside the realm of "high art," which valued originality, profound expression, and critical engagement over mere entertainment or decoration.

However, this critical dismissal stands in stark contrast to the works' immense and enduring popularity with the general public. The images became ubiquitous in American homes, game rooms, bars, and popular media. They resonated with a wide audience who appreciated their humor, relatability, and the charming absurdity of dogs behaving like humans.

In more recent times, there has been a degree of art historical re-evaluation, or at least a more nuanced appreciation, of Coolidge's work. While still not typically placed alongside the great masters of American art like Winslow Homer or Thomas Eakins, his paintings are increasingly recognized as significant pieces of Americana and popular visual culture. They reflect certain aspects of American society at the turn of the 20th century – its leisure activities, its social dynamics, and its embrace of a certain kind of accessible, narrative art. Artists like Norman Rockwell, who also focused on narrative scenes of American life and achieved immense popular appeal while sometimes facing critical condescension, occupy a somewhat similar space in bridging "illustration" and "fine art," though Rockwell's technical skill and emotional range were arguably greater.

The very definition of "kitsch" has also evolved, with some scholars and critics arguing that objects of kitsch can acquire cultural significance and even a certain aesthetic value over time, precisely because of their widespread adoption and their reflection of popular tastes. Coolidge's dogs have certainly achieved this status.

Coolidge in the Auction House: A Posthumous Vindication

The art market has also offered a form of posthumous vindication for Coolidge. While he was paid modestly for his original commission from Brown & Bigelow, his original paintings have fetched surprisingly high prices at auction in recent decades, indicating a strong collector interest that transcends mere novelty.

In 2005, two of his original "Dogs Playing Poker" paintings, A Bold Bluff and Waterloo, were sold as a pair at a Doyle New York auction. Expected to fetch between $30,000 and $50,000, they astounded many by selling for $590,400 to a private collector. This sale brought significant media attention to Coolidge and his work.

Even more remarkably, in November 2015, Coolidge's 1894 painting Poker Game (predating the Brown & Bigelow series but featuring the same theme) was sold at Sotheby's in New York for $658,000, exceeding its high estimate of $600,000. These auction results demonstrate that, regardless of their critical standing in some circles, Coolidge's original works are highly valued as unique pieces of American art and cultural history. The scarcity of the original sixteen Brown & Bigelow oils (many of which remain with the company or in private collections) further enhances their desirability.

The Enduring Paw Print: Coolidge's Impact on Popular Culture

The most undeniable aspect of Coolidge's legacy is the pervasive influence of his "Dogs Playing Poker" images on popular culture. They have been endlessly parodied, referenced, and homaged in virtually every medium:

Television: Episodes of numerous shows, from The Simpsons (where Santa's Little Helper is seen playing poker with other dogs) to Cheers (a print famously hung in Sam Malone's office), Family Guy, and even children's cartoons, have featured direct parodies or visual gags based on Coolidge's paintings. The animated series Rick and Morty featured a scene with sentient dogs playing poker on another planet, a clear nod to Coolidge.

Film: The imagery has appeared as set dressing or as a cultural reference point in various movies.

Advertising: Ironically, the images originally created for advertising have themselves been parodied in later advertising campaigns for a multitude of products.

Music: Album covers and music videos have sometimes incorporated the motif.

Merchandise: The "Dogs Playing Poker" theme has been reproduced on countless items, from posters and T-shirts to coffee mugs, mousepads, and, of course, playing cards.

This widespread cultural saturation means that even people who do not know Cassius Marcellus Coolidge's name are intimately familiar with his creations. The images have become a kind of visual shorthand, instantly recognizable and often used to evoke themes of male bonding, friendly competition, or slightly illicit fun. Their appeal lies in their humor, their narrative quality, and the charming absurdity of their premise. They have become a part of the American visual lexicon.

Beyond the Poker Table: Other Works and Signature Style

While "Dogs Playing Poker" is his claim to fame, Coolidge did produce other works. His early cartoons and the "comic foregrounds" were significant in their own right. He also painted other anthropomorphic animal scenes for Brown & Bigelow that didn't involve poker, such as dogs playing baseball or attending a formal dance. His signature, often "C.M. Coolidge," sometimes appeared with the playful addition of "Kash," a nod to his nickname and perhaps a self-aware comment on the commercial nature of his art. This unique signature habit, sometimes "Kash" or "Kash Coolidge," reflected his quirky and humorous personality.

His artistic output, though focused, consistently displayed a talent for narrative and an understanding of what would appeal to a broad audience. He was, in essence, a storyteller who used paint and canvas, and his chosen subjects – anthropomorphic dogs – provided a humorous and disarming way to reflect human behaviors and social situations.

Conclusion: An Unconventional Icon

Cassius Marcellus Coolidge remains a fascinating figure in American art history. A self-taught artist with a diverse entrepreneurial background, he created a series of images that, despite their commercial origins and initial critical dismissal, have achieved iconic status. His "Dogs Playing Poker" paintings are more than just humorous novelties; they are a window into early 20th-century American leisure, a testament to the power of mass-produced imagery, and a beloved, if unconventional, part of the nation's cultural heritage.

While he may not have directly interacted with or been influenced by a wide circle of famous contemporary "fine" artists like John Singer Sargent or Mary Cassatt, his work exists in a dialogue with a rich tradition of popular illustration, genre painting, and anthropomorphic art, drawing from predecessors like Landseer and Grandville, and creating a legacy that continues to inspire amusement and recognition today. The fact that his works command high prices at auction and are endlessly reproduced and parodied speaks to their unique and enduring appeal. Coolidge, the man of many hats, ultimately found his most lasting success at the poker table, surrounded by a pack of unforgettable canines who continue to deal their hands in the popular imagination. His contribution, while perhaps not "high art" in the traditional sense, is an undeniable and cherished thread in the rich tapestry of American visual culture.