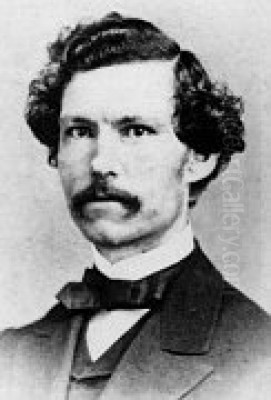

Alonzo Chappel stands as a significant, albeit sometimes debated, figure in the landscape of American art. Born in New York City in 1828, he dedicated his career to visualizing the pivotal moments and iconic figures of American history, particularly the eras of the Revolution and the Civil War. Living and working primarily in his native city until his death in 1887, Chappel became one of the most prolific historical painters and illustrators of his time, his work shaping the visual understanding of the nation's past for generations of Americans.

New York Roots and Early Talent

Chappel's artistic journey began remarkably early, rooted in the bustling environment of nineteenth-century New York City. Born into a family of modest means, his innate talent for drawing manifested quickly. Sources suggest he was already engaged in illustration work by the tender age of nine. By twelve, the young Chappel was reportedly earning money as a street artist in Manhattan, charging between five and ten dollars for portraits sketched directly from life. This early immersion in capturing likenesses likely honed his observational skills and provided a foundation for his later, more complex historical compositions.

Unlike many prominent artists of his era, Chappel did not receive extensive formal academic training in his youth. His skills were largely developed through persistent self-study and practical experience. This path, while perhaps less conventional, imbued his work with a certain directness and narrative focus, aimed at engaging a broad audience rather than solely appealing to academic sensibilities. His early years spent drawing on the streets provided invaluable experience in capturing human expression and form quickly and effectively.

Forging an Artistic Path

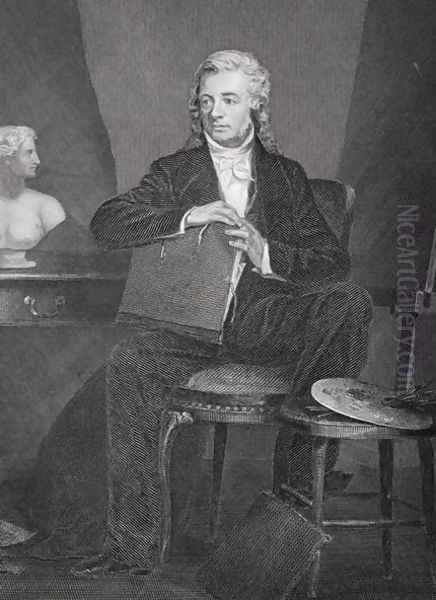

As Chappel matured, his focus shifted from simple portraiture towards the more ambitious genre of historical painting and illustration. A key influence in his technical development, particularly concerning printmaking, was the renowned artist and inventor Samuel F.B. Morse. While Morse is perhaps more famous today for his contributions to telegraphy, he was also a respected painter and the first president of the National Academy of Design. Exposure to Morse's work, or perhaps even direct guidance, likely informed Chappel's understanding of composition and the translation of painted images into engraved forms suitable for mass reproduction.

This transition marked a pivotal point in his career. He moved from capturing individual likenesses to reconstructing complex historical events, populated by multiple figures and imbued with national significance. This required not only artistic skill but also historical research and a flair for dramatic storytelling, elements that would become hallmarks of his mature style. His self-directed learning continued as he absorbed the visual language of historical representation prevalent in his time.

Transatlantic Echoes: Influences from Abroad

While largely self-taught, Chappel's artistic vision was undoubtedly shaped by the prevailing trends in historical painting, both American and European. The provided information notes influences from major figures like the Anglo-American painter Benjamin West, whose grand historical canvases had set a precedent for depicting recent history with classical gravity. West, who became President of the British Royal Academy, had mentored an earlier generation of American artists, including John Trumbull, another key figure in American historical painting known for his depictions of the Revolutionary War.

Chappel also looked towards European contemporaries. Emanuel Leutze, a German-American painter associated with the Düsseldorf school, was a significant influence. Leutze's own dramatic historical works, most famously Washington Crossing the Delaware, shared Chappel's penchant for theatrical composition and patriotic fervor. The Düsseldorf Academy's emphasis on detailed realism and narrative clarity resonated throughout the mid-nineteenth century. Furthermore, the influence of French academic painter Paul Delaroche is noted. Delaroche was celebrated for his meticulously rendered historical scenes, often focusing on moments of intense human drama, a quality Chappel frequently sought in his own work. These influences provided Chappel with models for constructing large-scale narrative paintings. The portrait tradition, essential for depicting historical figures, was also strong in America, carried by artists like Thomas Sully.

Chronicler of the Revolution

The American Revolution provided Chappel with a deep wellspring of subjects. He dedicated considerable effort to depicting the foundational moments and key figures of this era. His paintings aimed to capture the spirit of sacrifice, heroism, and nation-building associated with the period. These works often featured dynamic compositions, dramatic lighting, and a focus on the emotional intensity of the depicted events.

Among his notable works on this theme is the Signing of the Declaration of Independence. While John Trumbull had famously depicted this scene earlier, Chappel offered his own interpretation, likely aiming for wide circulation through engravings. He also created portraits of key figures, such as his Portrait of Washington, reportedly painted for an American Academy Fair. Battle scenes were a recurring subject, including depictions of the Battle of Camden and the Battle of Kings Mountain, both significant engagements in the Southern theater of the war. Another mentioned work, the Battle of Brunswick, likely refers to events involving Hessian troops (associated with the Duchy of Brunswick) during the New Jersey campaigns of 1776-1777, perhaps related to the battles of Trenton or Princeton, showcasing the hardships and conflicts of the war.

Visualizing the Civil War

The American Civil War, occurring during Chappel's mature career, offered immediate and potent subject matter. He produced numerous works depicting the battles, leaders, and poignant moments of this national trauma. These paintings and illustrations contributed to the public's understanding and memory of the conflict, often emphasizing themes of union, sacrifice, and the leadership required during crisis.

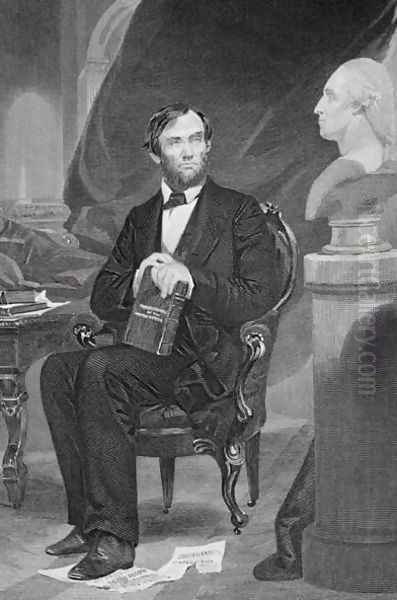

His depiction of the Battle of Gettysburg stands as a major example, tackling one of the war's most decisive and iconic engagements. Similarly, his painting of the Battle of Booneville (likely the Battle of Boonville, Missouri, 1861) captured an early conflict in the Western Theater. Chappel also addressed the human cost of the war, notably in his Death of Abraham Lincoln, a somber portrayal of the assassinated president's final moments, reflecting the nation's grief. His Portrait of Lincoln, published around 1870, contributed to the visual iconography of the revered leader. Compared to artists like Winslow Homer or Alfred Waud, who often sketched scenes directly from the field, Chappel's Civil War works were typically more formal, studio-based compositions, designed for historical commemoration rather than immediate reportage.

Beyond the Battlefields: Diverse Historical Narratives

While the Revolution and Civil War dominated his historical output, Chappel's interests extended to other periods and themes in American history. He explored earlier colonial encounters and foundational myths, demonstrating a broader engagement with the nation's past. These works often carried similar thematic weight, exploring moments of cultural contact, settlement, and the challenges faced by early colonists.

His painting The Landing of Roger Williams (1857) depicts the arrival of the theologian and advocate for religious freedom in Rhode Island in 1636, a key moment in the history of American religious tolerance. Another well-known work is Pocahontas Saving Captain John Smith (1861), created as part of Spencer's History of the United States. This painting tackles one of America's most enduring, though historically debated, legends, reflecting the nineteenth-century fascination with interactions between Native Americans and European settlers. These works showcase Chappel's ability to adapt his dramatic style to different historical contexts, contributing to a popular visual narrative of America's origins.

The Illustrator's Hand: Proliferation through Print

A crucial aspect of Alonzo Chappel's career and legacy lies in his work as an illustrator, particularly his long-standing collaboration with the New York publishing firm Johnson, Fry & Company (later Johnson & Wilson). Many of his most famous images were created specifically for publication in popular historical books and biographical collections. These included multi-volume works like Duyckinck's National Portrait Gallery of Eminent Americans and Jesse Ames Spencer's History of the United States.

Chappel's oil paintings served as the basis for steel engravings, a medium capable of producing detailed and durable printing plates suitable for large print runs. This process allowed his interpretations of American history to reach an exceptionally wide audience, appearing in homes, schools, and libraries across the country. He became, in effect, one of the primary visualizers of America's past for the common reader. This reliance on engraving, however, meant his work often circulated in black and white, mediated through the engraver's interpretation. He worked alongside prominent illustrators of the day, such as Felix O.C. Darley, who also contributed significantly to illustrated publications.

The sheer volume of reproductions had a complex effect on his reputation. While it made him widely known, it also led to a situation where the engravings became more familiar than the original paintings. The source material mentions an anecdote where the phrase "original oil painting based on Chappel's oil painting" emerged, possibly referring to copies made after his popular engraved images, highlighting the complex relationship between his painted originals and their mass-produced counterparts. This widespread reproduction undoubtedly cemented his influence but sometimes obscured the nuances of his original canvases.

Style and Substance: The Chappel Aesthetic

Alonzo Chappel's artistic style is firmly rooted in the Romanticism prevalent in the mid-nineteenth century, particularly as applied to historical subjects. His works prioritize narrative clarity, emotional impact, and dramatic effect. He typically employed dynamic compositions, often featuring prominent, full-length figures caught in moments of decisive action or significant contemplation. His goal was less archaeological reconstruction and more the conveyance of the perceived historical and moral significance of the event.

Heroism and leadership are recurring themes, with figures like Washington or Lincoln often depicted in commanding or poignant poses. He utilized strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten drama and focus attention. While striving for a degree of historical accuracy in costume and setting, his primary aim was storytelling. This sometimes led to criticism, both then and later, that his works could be overly theatrical or sacrifice nuanced detail for broader effect. His style can be contrasted with the more intimate, detailed genre scenes of contemporaries like Eastman Johnson, who also occasionally depicted historical themes but with a different focus. The influence of the Düsseldorf style, particularly via Emanuel Leutze, is evident in the emphasis on narrative and clear figural arrangement.

Navigating the Art World: Chappel and Contemporaries

Alonzo Chappel operated within a vibrant and evolving American art scene. While specific records of direct collaboration with many other painters are scarce, his career intersected with numerous key figures and movements. His influences, as noted, included the foundational Anglo-American history painter Benjamin West, the German-American Emanuel Leutze, and the French academic Paul Delaroche. His connection to Samuel F.B. Morse places him within the orbit of the National Academy of Design, where he did exhibit work.

He was a contemporary of the Hudson River School painters, such as Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, who were primarily focused on landscape as a defining American genre. While Chappel's focus was history, he shared the era's romantic sensibility. The mention of George Inness, a leading landscape painter known for his tonalist style, suggests Chappel was part of the broader New York artistic milieu, even if their primary subjects differed. His illustrative work placed him alongside figures like Felix O.C. Darley. In the context of Civil War imagery, his composed studio pieces differ from the direct reportage of Winslow Homer or Alfred Waud. Internationally, his historical paintings can be seen in the context of European academic painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme, who also specialized in dramatic historical and exotic scenes.

Reception, Reproduction, and Reputation

During his lifetime, Alonzo Chappel achieved considerable popular success. The widespread dissemination of his images through engravings ensured his name and work were familiar to a vast audience. His paintings tapped into a strong public appetite for patriotic historical narratives and compelling visual representations of the nation's heroes and defining moments. His work for publishers like Johnson, Fry & Co. was a mainstay of the illustrated book market.

However, his critical reputation was, and remains, somewhat complex. The sheer volume of his output, much of it destined for reproduction, led to variability in quality. Art critics sometimes found his work overly dramatic or lacking the subtlety and painterly finesse prized in academic circles. The overwhelming prevalence of engraved reproductions also meant that his original oil paintings were often overlooked or undervalued, their status complicated by the ubiquity of the prints. Despite these critiques, his work was exhibited at institutions like the National Academy of Design, indicating recognition within the formal art world.

Enduring Legacy

Alonzo Chappel's primary legacy lies in his role as a popularizer of American history through visual art. For decades, his paintings and illustrations provided a widely accessible visual vocabulary for understanding the nation's past. He translated complex historical events and biographies into dramatic, memorable images that resonated with a broad public. While art historians might debate the artistic merits of individual works or criticize occasional historical inaccuracies, his impact on the collective visual memory of America is undeniable.

His work reflects the patriotic fervor and narrative impulses of nineteenth-century America. He captured the drama, heroism, and tragedy of the nation's formative conflicts and key moments, creating images that were both informative and emotionally engaging. Though often mediated through the engraver's art, Chappel's vision shaped how millions of Americans pictured their history. He remains a key figure for understanding the intersection of art, history, and popular culture in the United States during a period of profound national definition and transformation. His numerous works continue to be studied as important documents of nineteenth-century American historical consciousness.