Nathaniel Currier stands as a pivotal figure in American art history, not primarily as a solitary painter wielding a brush, but as a master lithographer and visionary entrepreneur. His name, inextricably linked with that of his partner James Merritt Ives, evokes vivid images of nineteenth-century American life. The firm Currier & Ives, which he founded and led for decades, became synonymous with popular prints that documented and shaped the visual understanding of a nation undergoing profound transformation. Currier was an American citizen, born and raised in New England, and his life's work provides an unparalleled window into the aspirations, anxieties, and daily realities of his time.

Early Life and the Path to Lithography

Born on March 27, 1813, in Roxbury, Massachusetts, Nathaniel Currier entered a world on the cusp of industrial change. His early life was marked by hardship; his father passed away when Nathaniel was young, necessitating practical pursuits. This led him, at the age of fifteen, to an apprenticeship that would define his future. He joined the pioneering Boston lithography shop of William and John Pendleton. The Pendleton brothers were among the first to establish commercial lithography in the United States, making their workshop a crucial training ground.

Under the Pendletons' tutelage, Currier learned the intricacies of lithography, a relatively new printing technique based on the principle that oil and water repel each other. This process allowed for finer detail and easier reproduction than earlier methods like wood engraving. It was here that Currier mastered the craft, understanding both the artistic potential and the commercial possibilities of this burgeoning technology. His time with the Pendletons provided a foundation not just in technique, but likely also in the business of printmaking.

After his apprenticeship in Boston, Currier sought further experience. He spent time working in Philadelphia, another center for printing and publishing, honing his skills. By 1834, feeling prepared to strike out on his own, the ambitious twenty-one-year-old moved to New York City, the nation's rapidly growing commercial and cultural hub. This move marked the beginning of his independent career and set the stage for his future success.

Establishing a Business in New York

Upon arriving in New York City, Nathaniel Currier initially attempted a partnership. He briefly joined forces with a local printmaker named William Stodart, operating under the name Currier & Stodart in 1834. However, this collaboration proved short-lived, lasting only about a year. Undeterred, Currier established his own firm under his own name, listed as "N. Currier, Lithographer," around 1835, operating initially from locations on Wall Street and later Nassau Street.

His early business focused on job printing – producing commercial work like sheet music covers, letterheads, and advertisements using the lithographic process he had mastered. While practical, this work allowed him to build his business and reputation. He was known for quality and efficiency, essential traits in the competitive New York printing market. He was steadily building the foundation for what would become a printmaking empire.

Currier's ambition extended beyond routine commercial work. He possessed a keen sense for news and public interest. This instinct would soon lead to a breakthrough that dramatically altered the trajectory of his career and demonstrated the power of lithography to disseminate visual information quickly to a wide audience.

The Breakthrough: Disaster and Visual News

A pivotal moment for Nathaniel Currier's business arrived in January 1840. A devastating fire consumed the steamboat Lexington on Long Island Sound, resulting in a tragic loss of life. Recognizing the public's intense interest in the event, Currier acted swiftly. Within just three days of the disaster, he produced a detailed lithographic print titled Awful Conflagration of the Steamboat Lexington.

Working quickly, likely collaborating with an artist to sketch the scene based on newspaper accounts, Currier created the lithographic stone and printed copies. He distributed them through newsboys and street vendors. The print was an immediate sensation. Its timeliness and dramatic depiction captured the public imagination, selling thousands of copies and establishing N. Currier as a purveyor of visual news.

This success marked a turning point. Currier realized the immense market for affordable, topical images. The Lexington print is often cited as one of the earliest examples of illustrated news reporting in America, predating the widespread use of illustrations in newspapers like Harper's Weekly or Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. It demonstrated Currier's entrepreneurial acumen and his understanding of lithography's potential to connect with a mass audience hungry for visual information about current events. From this point forward, disaster prints became a recurring, albeit somber, staple of his output.

Forging a Partnership: The Arrival of James Merritt Ives

As Currier's business flourished, the demands of managing production, finances, and distribution grew. In 1852, Currier hired James Merritt Ives (1824-1895) as a bookkeeper. Ives, who was Currier's brother-in-law (married to Caroline Clark, the sister of Currier's second wife, Lura Clark), proved to be much more than just an accountant. He possessed a strong business sense, an eye for popular taste, and organizational skills that complemented Currier's artistic and technical expertise.

Ives quickly demonstrated his value, contributing significantly to the firm's management and helping to gauge public preferences for print subjects. Recognizing Ives's indispensable contributions, Currier offered him a full partnership in 1857. The firm was officially renamed "Currier & Ives," a name that would become legendary in American popular culture.

While Currier remained the driving force behind the technical and artistic production, Ives focused on the financial and marketing aspects. He had a knack for understanding what subjects would sell, often favoring sentimental, patriotic, or idyllic scenes that appealed to the values and aspirations of the American middle class. Their partnership was a synergistic blend of craft, artistry, and commercial savvy, perfectly positioning the firm for decades of unparalleled success.

The Currier & Ives Business Model: "Printmakers to the American People"

Currier & Ives proudly billed themselves as "the Grand Central Depot for Cheap and Popular Prints" and later adopted the slogan "Publishers of Cheap and Popular Pictures." Their business model was built on mass production and wide distribution, making art accessible to average Americans in an unprecedented way. Before Currier & Ives, art ownership was largely confined to the wealthy elite who could afford original paintings or expensive engravings.

The core of their operation was lithography. Artists, either staff or freelance, would create an image, often initially as a drawing or painting. This image was then meticulously drawn by a lithographic artist directly onto a large, flat limestone block (or later, zinc plates) using a greasy crayon. The stone was then treated chemically so that ink would adhere only to the drawn lines. Paper was pressed against the inked stone, transferring the image.

For color prints, the process was initially labor-intensive. Black and white prints were produced first. Then, teams of colorists, often young women (many of them German immigrants), worked assembly-line style in the New York workshop. Each woman would apply a single color by hand to a specific area of the print, passing it down the line until all colors were added, guided by a master color proof. This method allowed for rapid, inexpensive coloring, though variations in color application are common among surviving prints. Later, the firm adopted chromolithography for some prints, using multiple stones (one for each color) to print colors mechanically, though hand-coloring continued throughout the firm's history.

Prints were sold for remarkably low prices, ranging from five cents for small uncolored prints to three dollars for large, colored folio prints. They were distributed through a vast network, including pushcart peddlers, mail-order catalogues, retail stores across the country, and even outlets abroad. This combination of affordability, appealing subject matter, and extensive distribution cemented Currier & Ives's place in American homes.

A Nation Reflected: Themes and Subjects

The sheer breadth of subjects depicted by Currier & Ives is staggering, offering a panoramic view of nineteenth-century American life, ideals, and interests. Their catalogue eventually numbered over 7,500 different titles, produced in quantities estimated in the millions.

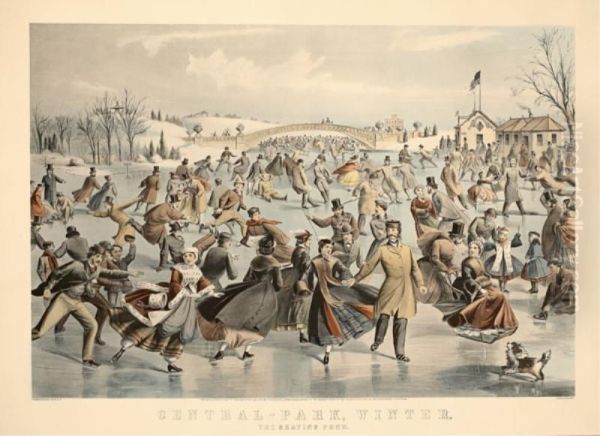

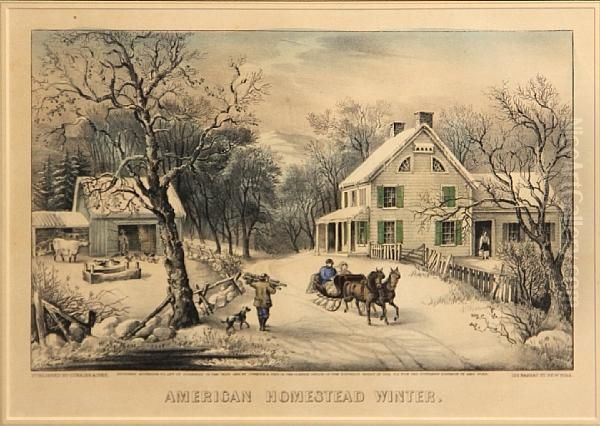

Rural and domestic scenes were immensely popular, depicting idealized visions of farm life, cozy homesteads, family gatherings, and seasonal activities. Prints like the American Homestead series (Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter) tapped into a nostalgic yearning for agrarian simplicity, even as the nation rapidly industrialized and urbanized. Winter scenes, particularly those featuring sleigh rides or skating, became iconic images of American holidays, contributing significantly to the visual culture of Christmas.

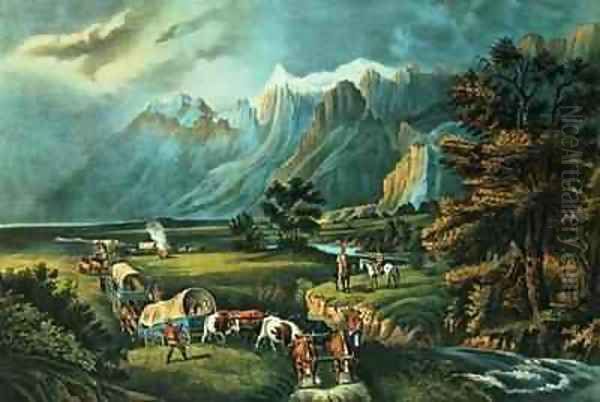

The firm documented the nation's expansion and technological progress. Images of clipper ships racing across the ocean, steamships navigating rivers like the Mississippi, and railroads traversing the continent (such as Across the Continent: Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way) celebrated American ingenuity and manifest destiny. Majestic landscapes, particularly scenes of the American West like The Rocky Mountains – Emigrants Crossing the Plains, captured the grandeur of the continent, often drawing inspiration from painters of the Hudson River School, though adapted for popular consumption.

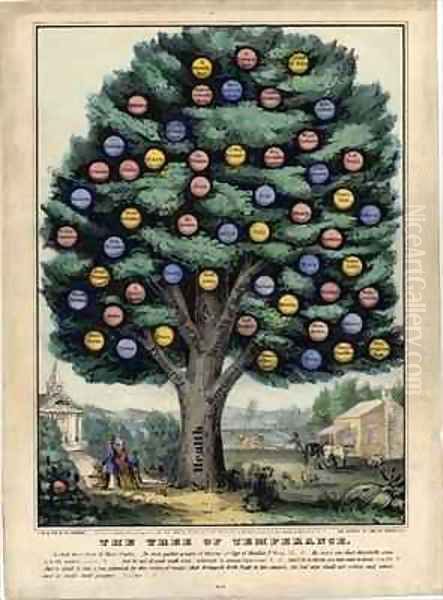

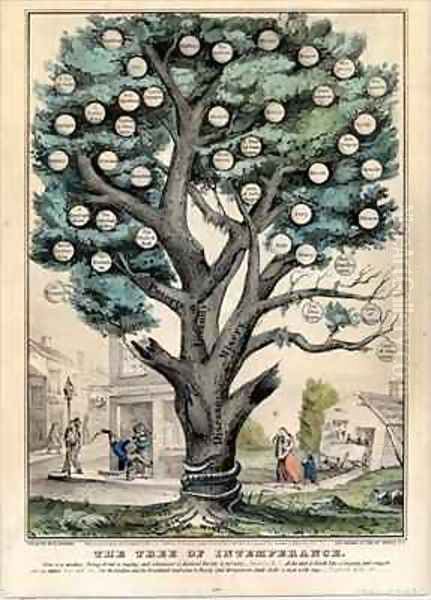

Current events remained a staple. Currier & Ives produced numerous prints related to the American Civil War, depicting battles, camp life, and portraits of generals. They also covered political campaigns, sporting events (especially horse racing, boxing, and baseball), famous racehorses, hunting and fishing scenes, and dramatic events like fires and shipwrecks. Sentimental subjects, including courtship, childhood, and religious themes, were also common, catering to Victorian sensibilities. Humorous and satirical prints, sometimes touching on social issues like temperance (e.g., The Tree of Temperance vs. The Tree of Intemperance), also found a market.

Artistic Style and Technique

The characteristic style of Currier & Ives prints is recognizable, though it evolved over time and varied depending on the subject and the artist involved. Generally, the style prioritized clarity, narrative, and accessibility over artistic experimentation or profound emotional depth. It was a blend of realism in detail and often romanticism or idealization in overall mood and composition.

Lithography itself influenced the style. The process allowed for strong lines, clear forms, and relatively subtle shading through techniques like stippling and cross-hatching with the lithographic crayon. The hand-coloring, while efficient, often resulted in bright, somewhat flat areas of color, contributing to the prints' distinctive, vibrant look. There was less emphasis on the atmospheric effects and nuanced light found in contemporary oil paintings by artists like George Inness or the later works of Winslow Homer.

While Nathaniel Currier himself was a skilled lithographer, the firm employed numerous talented artists to create the original images. These artists often specialized in particular subjects. Their individual styles were sometimes evident, but the final prints generally adhered to a consistent "house style" that emphasized legibility and popular appeal. The goal was not personal artistic expression in the modern sense, but the creation of marketable images that told a story or depicted a scene clearly and engagingly for a broad audience.

Key Artists of the Firm

While Nathaniel Currier and James Ives oversaw the operation, the actual images were often created by a team of talented, though sometimes overlooked, artists. These individuals translated ideas and sketches into the detailed drawings on the lithographic stones.

One of the most prolific and important artists for the firm was Frances Flora Bond Palmer (1812-1876), known as Fanny Palmer. An English immigrant, she was incredibly versatile, producing landscapes, sporting scenes, still lifes, and views of technological progress. She is credited with creating some of the firm's most iconic images, including many of the Mississippi River steamboat scenes and detailed landscapes like The Rocky Mountains – Emigrants Crossing the Plains. Her skill in composition and detail was exceptional.

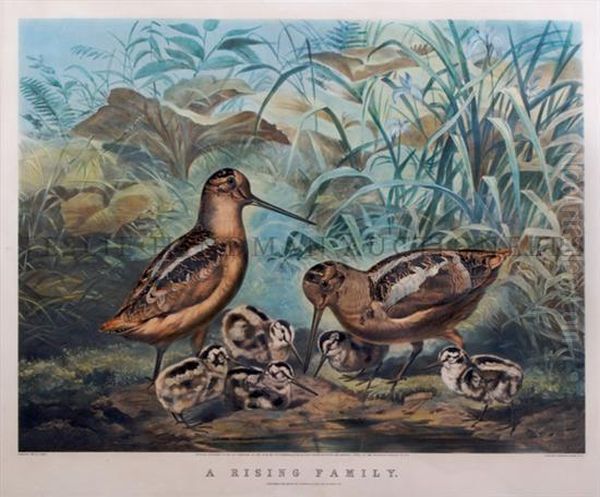

Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819-1905), another English-born artist, specialized in sporting and animal scenes, particularly images of hunting, fishing, and wildlife in the American wilderness, often set in the Adirondack Mountains. His works, like A Rising Family (featuring quail), were highly popular and captured the rugged, adventurous spirit associated with the American outdoors. Many of Tait's paintings were reproduced as Currier & Ives lithographs.

Louis Maurer (1832-1932), a German immigrant, was known for his dynamic depictions of horses and fire engines. He created many of the firm's most famous horse racing prints, capturing the speed and excitement of the track. His long life allowed him to witness the entire arc of the firm's history and beyond.

George Henry Durrie (1820-1863) was a Connecticut painter whose charming New England winter landscapes became a signature genre for Currier & Ives. Though he died relatively young, the firm continued to reproduce his scenes of snow-covered farms and sleigh rides, solidifying their association with idyllic American winters. Other notable artists included Charles Parsons, who specialized in marine subjects and disaster scenes (including the Lexington), and James E. Butterworth, known for his yachting prints.

Notable Works: A Visual Legacy

Among the thousands of prints produced, several stand out as particularly iconic or representative of the firm's output:

Awful Conflagration of the Steamboat Lexington (1840): As mentioned, this early print established Currier's reputation for timely visual news and demonstrated the commercial potential of disaster imagery.

Across the Continent: Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (1868): This famous print captures the spirit of Manifest Destiny, showing a railroad pushing westward, dividing untouched wilderness from settled land with a town and schoolhouse, symbolizing progress and civilization's advance. Fanny Palmer is often credited with the design.

The Rocky Mountains – Emigrants Crossing the Plains (1866): Another masterpiece attributed to Fanny Palmer, this large folio print depicts a wagon train moving through a dramatic mountain landscape, embodying the challenges and grandeur of westward migration.

Central Park, Winter: The Skating Pond (1862): This lively scene, designed by Charles Parsons, captures the fashionable social life of New York City, showing crowds enjoying skating in the newly created Central Park. It exemplifies the firm's depiction of urban leisure.

American Homestead Series (e.g., American Homestead Winter, c. 1868): Often based on paintings by George Durrie, these prints presented an idealized vision of rural American life, emphasizing family, security, and harmony with nature, becoming enduring symbols of nostalgic Americana.

The Life of a Fireman Series (1854-1866): Created by Louis Maurer, these prints depicted the heroic efforts of volunteer firefighters, showcasing dramatic scenes of rescue and the impressive steam-powered fire engines of the era.

Champions of the Trotting Turf: Currier & Ives produced countless prints of famous racehorses like Dexter, Goldsmith Maid, and Maud S., catering to the huge public interest in harness racing.

These examples represent just a fraction of the firm's vast output, but they illustrate the range of themes and the enduring appeal of Currier & Ives imagery.

Context and Contemporaries: Printmaking and Painting

Currier & Ives operated within a vibrant and evolving nineteenth-century American art world. While they dominated the popular print market, they were not alone. Other lithography firms existed, such as the Kellogg brothers (E.B. & E.C. Kellogg) of Hartford, Connecticut, who also produced popular prints, though on a smaller scale. Later in the century, Louis Prang, based in Boston, became famous for his high-quality chromolithographs, particularly Christmas cards and reproductions of fine art, representing a different segment of the print market that emphasized finer artistic quality over the news-oriented or broadly popular approach of Currier & Ives.

In the realm of painting, Currier & Ives's work often paralleled, yet differed significantly from, the major artistic movements of the time. Their landscape prints shared subjects with the Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church, and Albert Bierstadt, who celebrated the majesty of the American wilderness. However, Currier & Ives prints typically simplified and romanticized these scenes for popular appeal, lacking the detailed naturalism or sublime spiritual undertones of the major landscape painters.

Similarly, their scenes of everyday life overlapped with the work of genre painters like Eastman Johnson and Winslow Homer, who captured nuanced observations of American society. Again, Currier & Ives prints tended towards more generalized, often sentimental or anecdotal depictions compared to the psychologically deeper or more critically observant works of these painters. Currier & Ives were not aiming for the status of "high art" in the same way as these painters; their goal was mass communication and commercial success through accessible imagery. They democratized art, bringing pictures into homes that might never contain an original oil painting.

Controversy and Criticism

While Currier & Ives prints are often celebrated for their historical value and nostalgic charm, they are not without controversy. One significant area of criticism concerns their production of racist caricatures, particularly the "Darktown Comics" series popular in the 1880s and 1890s (after Currier's retirement but under the firm's name). These prints depicted African Americans in grossly stereotyped and demeaning ways, pandering to and reinforcing the prevalent racial prejudices of the era. While reflecting a lamentable aspect of late nineteenth-century American culture, these images are deeply offensive by modern standards and complicate the firm's legacy.

Artistically, Currier & Ives prints have sometimes been dismissed by critics as mere commercial products, lacking the originality, depth, and technical sophistication of fine art painting or etching. Their tendency towards sentimentality and idealization has also drawn criticism. However, other historians and critics argue that their value lies precisely in their status as popular art – reflecting the tastes, values, and visual language understood by the majority of Americans at the time. They are invaluable documents of social history, visual culture, and the development of mass media.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Appeal

Nathaniel Currier remained actively involved in the firm until his retirement in 1880. He passed away on November 20, 1888, leaving behind a formidable legacy. James Ives continued with the firm, bringing in his son Chauncey Ives and Currier's son Edward West Currier. The firm continued operating after James Ives's death in 1895.

However, by the turn of the century, the market for lithographic prints began to decline. The rise of photography and photo-mechanical reproduction processes offered new, faster, and eventually cheaper ways to create and disseminate images. Public tastes also changed. The firm officially closed its doors in 1907. The lithographic stones were sold off or destroyed, marking the end of an era.

Despite the firm's closure, the legacy of Nathaniel Currier and Currier & Ives endured. Their prints became highly sought after by collectors in the twentieth century, appreciated both as antiques and as evocative windows into America's past. Museums now hold extensive collections, recognizing their importance as historical documents and examples of popular visual culture.

Nathaniel Currier's genius lay not only in his mastery of lithography but also in his entrepreneurial spirit and his intuitive understanding of his audience. He and James Ives created a visual record of their time that was unparalleled in its scope and reach. Their prints informed, entertained, and decorated the homes of millions, shaping America's collective memory and visual identity in ways that continue to resonate today. They were, truly, the "Printmakers to the American People."

Conclusion

Nathaniel Currier was more than just a printmaker; he was a visual historian and a pioneer of mass media in America. From his early apprenticeship learning the craft of lithography to co-founding and leading the immensely successful firm of Currier & Ives, his career spanned a transformative period in American history. Through affordable, accessible prints, he and his partner James Merritt Ives captured the essence of nineteenth-century America – its landscapes, its people, its technological triumphs, its daily life, and its defining events. While subject to critique, the vast body of work produced under his name remains an invaluable resource for understanding the nation's past and a testament to the power of popular imagery. Nathaniel Currier's contribution lies in democratizing art and creating an enduring visual chronicle of his time.