Charles Angrand stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. A dedicated painter and a thoughtful intellectual, Angrand navigated the currents of Impressionism before becoming a pivotal member of the Neo-Impressionist movement. His unique application of Pointillist techniques, characterized by a subtle luminosity and poetic sensibility, distinguished his work from that of his contemporaries. This exploration delves into the life, artistic evolution, key relationships, and enduring legacy of a painter who quietly, yet profoundly, contributed to the course of modern art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Normandy

Born on April 19, 1854, in the modest village of Criquetot-sur-Ouville, Normandy, Charles Théophile Angrand's early life was steeped in the rural landscapes that would later feature prominently in his art. Normandy, with its distinctive light and pastoral scenery, had already captivated artists like Gustave Courbet and was becoming a crucible for the burgeoning Impressionist movement, with painters such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro frequently working in the region.

Angrand's formal artistic training began at the École des Beaux-Arts et de Dessin in Rouen, the historical capital of Normandy. Here, he would have received a traditional academic grounding. However, the artistic ferment of the era, particularly the revolutionary ideas emanating from Paris, undoubtedly reached him. During these formative years, he supported himself by teaching, a profession he would return to later in life. His early artistic inclinations were shaped by the prevailing Realist traditions, but also by the emerging Impressionist aesthetic, which emphasized capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light and atmosphere. Artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage, known for his sensitive portrayals of rural life, were significant influences on many young painters of Angrand's generation, blending academic technique with a more naturalistic observation.

The Parisian Crucible: Teaching and the Avant-Garde

In 1882, Angrand made the pivotal decision to move to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world. This move marked a turning point in his career and personal development. He secured a position as a mathematics teacher at the Collège Chaptal, a role that provided him with financial stability and allowed him the freedom to pursue his artistic passions without the immediate pressure of sales. Teaching mathematics, a discipline requiring precision and logical thought, perhaps subtly informed his later systematic approach to color and form in Neo-Impressionism.

Paris in the 1880s was a hotbed of artistic innovation and debate. The Impressionist movement, having already challenged academic conventions for over a decade, was itself evolving. Angrand quickly immersed himself in the city's avant-garde circles. It was here that he forged crucial friendships that would shape his artistic trajectory. Most notably, he connected with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, two artists who were at the forefront of developing a new, more scientific approach to painting based on optical theories of color. These encounters were transformative, steering Angrand towards the nascent Neo-Impressionist movement.

The Emergence of Neo-Impressionism and Angrand's Role

The mid-1880s witnessed the birth of Neo-Impressionism, a movement that sought to bring a more structured and scientific methodology to the Impressionists' intuitive exploration of light and color. Georges Seurat was the principal innovator, developing the technique of Divisionism (often referred to as Pointillism), where colors were applied in small, distinct dots or dabs, intended to mix optically in the viewer's eye rather than on the palette. This method was heavily influenced by the color theories of scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood.

Charles Angrand was an early and enthusiastic adopter of these new ideas. He, along with Seurat, Signac, Camille Pissarro (who briefly adopted the technique), Henri-Edmond Cross, and Albert Dubois-Pillet, became a core member of this new school. In 1884, Angrand was a co-founder of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. This artist-run organization was established as a radical alternative to the official Salon, allowing artists to exhibit their work without the judgment of a conservative jury. The Salon des Indépendants became the primary venue for showcasing Neo-Impressionist works, and Angrand exhibited there regularly, gaining recognition for his contributions.

Angrand's engagement with Neo-Impressionism was not merely imitative. While he embraced the principles of Divisionism, his application of the technique developed a distinct character. His palette often tended towards more muted, harmonious tones compared to the sometimes more vibrant and contrasting colors used by Seurat or Signac. He was particularly adept at capturing subtle atmospheric effects and the gentle play of light, especially in his depictions of rural scenes and crepuscular landscapes.

Angrand's Unique Pointillist Vision

While Georges Seurat is often credited as the father of Pointillism, and Paul Signac its most ardent propagandist and theorist after Seurat's early death, Charles Angrand carved out his own niche within the movement. His Pointillism was less about rigid adherence to scientific dogma and more about achieving a particular poetic and atmospheric quality. His dots were often finer and more blended, creating a softer, more ethereal effect than the more distinctly separated points of Seurat.

Angrand's works from this period often depict the quiet beauty of the French countryside, the tranquil banks of the Seine, or intimate interior scenes. He was a master of chiaroscuro, using the Pointillist technique to build up subtle gradations of light and shadow, imbuing his canvases with a sense of calm and introspection. His understanding of color harmony allowed him to create works that were both structurally sound, in keeping with Neo-Impressionist principles, and emotionally resonant. He demonstrated a particular sensitivity to the nuances of twilight and dawn, capturing the delicate interplay of colors during these transitional moments of the day.

This period saw him create some of his most celebrated works. He was less interested in the bustling urban scenes that captivated some of his contemporaries, preferring the solitude and timeless quality of rural life. His figures, when present, are often integrated harmoniously into the landscape, part of a larger, unified whole. This focus on atmosphere and a more subdued palette set his work apart and showcased his individual artistic temperament.

Representative Works: A Testament to Light and Form

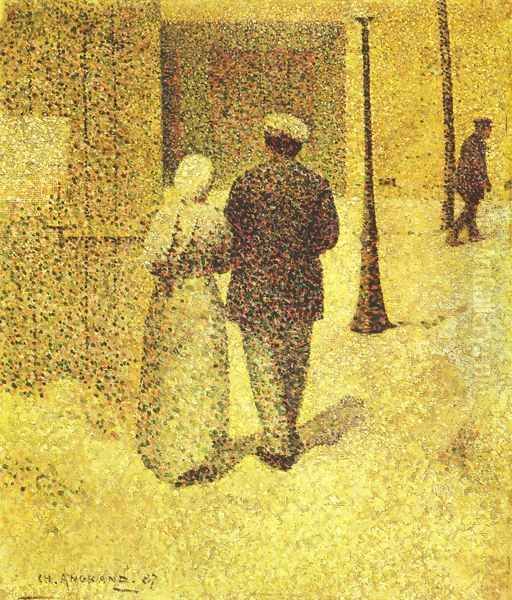

Several paintings stand out as exemplars of Angrand's artistic achievements. Couple on the Street (1887) is an early Neo-Impressionist work that demonstrates his ability to capture a fleeting urban moment with the new technique. The figures are rendered with a sense of quiet observation, and the dappled light filtering through trees showcases his burgeoning mastery of Divisionist principles.

Perhaps his most famous work is The Harvesters (1892). This large canvas depicts peasants working in a field under a luminous sky. The painting is a tour-de-force of Pointillist technique, with meticulously applied dots of color creating a vibrant yet harmonious scene. Angrand masterfully conveys the heat of the day and the rhythmic labor of the figures, all enveloped in a soft, golden light. It is a work that combines the Neo-Impressionist concern for optical science with a deep empathy for rural life, reminiscent of the earlier Realist tradition but filtered through a modern lens.

Pierre Bridge (1881), an earlier work, likely predates his full conversion to Pointillism but shows his Impressionistic roots and his keen eye for capturing the effects of light on water and stone. Later, works like Marie-Anne Garden would continue to explore themes of tranquility and nature, often employing a refined Pointillist or, in later years, a modified brushwork that retained a sense of structured color. His self-portraits, too, reveal a thoughtful and introspective artist, applying his characteristic technique to the human form.

His drawings and pastel works also form an important part of his oeuvre. In these media, Angrand often employed a technique of dense cross-hatching or stippling to achieve rich tonal variations, particularly in his evocative black and white conté crayon drawings, which possess a remarkable velvety depth and luminosity. These works often focused on scenes of labor or quiet domesticity, imbued with a profound sense of dignity.

The Société des Artistes Indépendants: A Platform for Innovation

The founding of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in 1884 was a landmark event in the history of modern art, and Charles Angrand was at its very inception. Frustrated by the restrictive and often biased jury system of the official Paris Salon, which favored academic art and was resistant to new forms of expression, a group of avant-garde artists decided to create their own exhibition platform. The motto "Sans jury ni récompense" (Without jury nor awards) encapsulated their democratic and inclusive vision.

Angrand, alongside Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Albert Dubois-Pillet, Odilon Redon, and others, played an instrumental role in establishing this society. It provided a crucial space for artists like the Neo-Impressionists, as well as Fauvists and Cubists in later years, to present their work to the public directly. Angrand exhibited regularly at the Salon des Indépendants from its inception until he largely withdrew from the Paris art scene. His participation helped to solidify the Neo-Impressionist presence and demonstrate the viability and aesthetic power of their innovative techniques. The Indépendants was not just an exhibition society; it was a community and a statement of artistic freedom, and Angrand's commitment to it underscored his belief in progressive artistic values.

Relationships and Artistic Dialogue

Angrand's artistic journey was deeply intertwined with his relationships with fellow artists. His friendship with Georges Seurat was particularly formative. They shared a deep intellectual connection and a commitment to exploring the scientific basis of color. Seurat's untimely death in 1891 at the age of 31 was a profound blow to Angrand, as it was to the entire Neo-Impressionist group. It is said that Angrand was deeply affected by this loss, which contributed to a period of re-evaluation in his own work.

Paul Signac became another lifelong friend and artistic comrade. After Seurat's death, Signac took on the mantle of leading and promoting Neo-Impressionism, and Angrand remained a respected, if more reserved, member of the circle. They often sketched together along the Seine and shared a commitment to the Divisionist technique, though their individual expressions of it diverged. Signac's work often featured brighter, more vibrant colors and a focus on coastal scenes, while Angrand maintained his preference for more subdued, atmospheric landscapes.

Angrand also maintained a correspondence with Vincent van Gogh. Van Gogh, who was in Paris from 1886 to 1888, was exposed to Neo-Impressionism and briefly experimented with Pointillist techniques. He admired Angrand's work, and their letters reveal a mutual respect. While their artistic paths ultimately differed significantly, this connection highlights Angrand's standing within the broader avant-garde community.

His early influences, Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, remained important reference points. Pissarro, the elder statesman of Impressionism, even adopted the Neo-Impressionist technique for a period in the late 1880s, exhibiting alongside Seurat, Signac, and Angrand. This demonstrates the fluidity and interconnectedness of the Parisian art scene. Other Neo-Impressionists like Henri-Edmond Cross and Maximilien Luce were also part of Angrand's circle, sharing exhibitions and artistic discussions. Luce, like Angrand, also held strong anarchist sympathies.

Anarchism and Artistic Conviction

Like many artists and intellectuals in late 19th-century France, including Paul Signac, Camille Pissarro, and Maximilien Luce, Charles Angrand harbored anarchist sympathies. This political leaning was not uncommon in avant-garde circles, which often positioned themselves against bourgeois conventions and state authority. Anarchism, with its emphasis on individual liberty and social justice, resonated with artists seeking to break free from academic constraints and create art that was both modern and socially conscious.

Angrand contributed illustrations to anarchist publications, such as Jean Grave's "Les Temps Nouveaux" (New Times), using his artistic skills to support the cause. While his paintings were not overtly political in their subject matter, his focus on rural laborers and his empathetic portrayal of everyday life can be seen as consistent with his social concerns. His political beliefs may have contributed to his somewhat reserved nature and his eventual withdrawal from the more competitive aspects of the Paris art world. For Angrand, artistic integrity and personal conviction were paramount, and he pursued his vision with quiet determination, regardless of prevailing trends or commercial pressures.

Challenges, Later Years, and Return to Normandy

The death of Georges Seurat in 1891 marked a significant turning point for Angrand. The loss of his close friend and artistic mentor was a severe blow. Following this, Angrand's output in oil painting decreased for a period. He began to spend more time away from Paris, eventually returning to his native Normandy. Around 1896, he largely ceased painting in oils and focused more on conté crayon drawings and pastels, media in which he produced works of exceptional quality and sensitivity.

His drawings from this period are particularly noteworthy, often depicting rural scenes, mothers and children, and farm animals with a profound sense of intimacy and monumentality. He used the conté crayon with remarkable skill, creating rich, velvety blacks and subtle gradations of tone that gave his subjects a sculptural presence. These works, while different in medium from his Pointillist paintings, retained a concern for light, form, and a certain structured approach to composition.

In 1913, he moved to Dieppe, another coastal town in Normandy, and later to Rouen. During these later years, he lived a more secluded life, though he continued to create art. He did return to oil painting to some extent, but his focus remained largely on works on paper. He was also associated with a regional group of artists in Normandy known as "Les Musquetaires," which included painters like Charles Frechon and Joseph Delattre, who were also exploring modern artistic idioms within a Norman context. Despite his withdrawal from the Parisian limelight, Angrand's reputation as a significant Neo-Impressionist endured. He passed away in Rouen on April 1, 1926.

Artistic Legacy and Enduring Influence

Charles Angrand's legacy is that of a dedicated and innovative artist who played a crucial role in the development of Neo-Impressionism. While perhaps not as widely known as Seurat or Signac, his contribution was unique and significant. His Pointillist works are celebrated for their subtle luminosity, harmonious color palettes, and poetic sensibility. He demonstrated that the scientific principles of Divisionism could be used to create art that was not only optically vibrant but also deeply expressive and atmospheric.

His works are held in numerous prestigious museum collections worldwide, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Finnish National Gallery. His paintings and drawings continue to be admired for their technical mastery and their quiet, contemplative beauty. Auction results for his major works, such as La Coruña, the Sea, attest to his enduring value in the art market.

Angrand's influence can be seen in his steadfast commitment to his artistic vision and his ability to adapt and evolve. His exploration of light and color within the framework of Neo-Impressionism provided an important model for other artists. Furthermore, his later work in conté crayon and pastel showcased his versatility and his profound ability to capture the essence of his subjects with economy and grace. He remains a testament to the quiet power of artistic integrity and the enduring appeal of art that combines intellectual rigor with emotional depth. His career reflects the dynamic exchanges within the Parisian avant-garde, from Impressionism through the scientific explorations of Neo-Impressionism, and his unique voice enriched the chorus of modern art.

Conclusion: A Quiet Master of Light

Charles Angrand's journey through the art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was marked by thoughtful innovation and a distinctive personal style. As a founding member of the Société des Artistes Indépendants and a key figure in the Neo-Impressionist movement, he contributed significantly to the shift away from academic art towards modernism. His nuanced application of Pointillist techniques, his mastery of light and atmosphere, and his empathetic portrayal of rural life and intimate scenes secure his place as a distinguished artist. Though he may have been more reserved than some of his contemporaries, the quality and integrity of his work speak volumes, leaving behind a legacy of luminous, poetic, and enduringly beautiful art. His life and work continue to inspire appreciation for the subtle yet profound ways an artist can contribute to the grand narrative of art history.