Elbridge Ayer Burbank stands as a significant, if sometimes complex, figure in the art of the American West. Active during a period of profound transition for Native American peoples, Burbank dedicated a substantial portion of his career to creating an extensive visual record of individuals from numerous tribes. His work, characterized by a commitment to direct observation and a sympathetic, if occasionally romanticized, portrayal, offers a valuable window into the lives and appearances of Native Americans at the turn of the 20th century. While his methods and the sheer volume of his output have invited discussion, his legacy as a prolific portraitist remains undeniable.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on August 10, 1858, in the town of Harvard, Illinois, Elbridge Ayer Burbank's early life set the stage for an artistic journey that would take him far from his Midwestern roots. His family background provided a degree of cultural exposure; notably, his maternal uncle was Edward E. Ayer, a prominent Chicago businessman, collector, and philanthropist who would later play a pivotal role in Burbank's career. This connection likely fostered an early appreciation for art and history.

Burbank's formal artistic training began at the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago, then known as the Chicago Academy of Design. Here, he would have been immersed in the academic traditions of the time, focusing on drawing from casts, life drawing, and the fundamentals of composition and color. This foundational education was crucial in honing the technical skills that would later define his portraiture. Like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Burbank sought further refinement in Europe. He traveled to Munich, Germany, a major art center rivaling Paris, to study. Munich was known for its strong tradition of realism and painterly technique, often characterized by dark palettes and vigorous brushwork, under masters like Wilhelm von Diez or Ludwig von Löfftz, whose influence was felt by many American artists studying abroad, such as William Merritt Chase and Frank Duveneck. This European sojourn, though reportedly brief, would have exposed Burbank to different artistic philosophies and techniques, broadening his artistic horizons before he returned to Chicago to embark on his professional career.

Forging a Path: Early Career and the Lure of the West

Upon his return to Chicago, Elbridge Ayer Burbank began to establish himself as a working artist. His initial professional endeavors included illustration work, a common path for artists seeking to make a living. A significant early commission came from The Northwest Magazine, a publication focused on promoting the regions accessible via the Northern Pacific Railway. This assignment was pivotal, as it sent Burbank into the American West, tasking him with documenting the landscapes, burgeoning settlements, and diverse cultures along the railway's expanding lines.

This immersion in the West was transformative. It provided Burbank with firsthand experience of the region's vastness, its natural beauty, and, crucially, its Native American inhabitants. The landscapes he sketched and painted during this period were more than just scenic views; they were environments that shaped the lives of the people he would soon dedicate his artistic life to portraying. This early work for The Northwest Magazine not only provided him with income and exposure but also ignited a profound interest in the indigenous peoples of America, an interest that would soon become the central focus of his artistic output. His experiences traveling through territories inhabited by tribes like the Crow, Blackfoot, and Sioux undoubtedly laid the groundwork for his later, more intensive ethnographic portraiture projects. This period can be seen as a precursor to the more focused and systematic documentation he would later undertake.

The Great Commission: Documenting Native America

The most defining phase of Elbridge Ayer Burbank's career was initiated and largely funded by his uncle, Edward E. Ayer. Ayer, a passionate collector of Americana and a key figure in the establishment of the Field Columbian Museum (now the Field Museum of Natural History) in Chicago, harbored a deep concern for what he, like many of his contemporaries, perceived as the vanishing cultures of Native American tribes. He envisioned a comprehensive visual archive of Native American leaders and individuals, a project of immense historical and ethnographical importance.

To this end, Edward E. Ayer commissioned his nephew, Elbridge, to travel extensively throughout the American West and create portraits of Native Americans. This was no small undertaking. Over several decades, Burbank journeyed to reservations, forts, and tribal lands, seeking out individuals from a vast array of different nations. His dedication was remarkable; he is credited with producing over 1200 portraits, representing individuals from more than 125 distinct tribes. This monumental effort places him among the most prolific painters of Native American subjects, comparable in scope, if different in style and intent, to earlier artists like George Catlin and Karl Bodmer, who also sought to document Native American life before it was irrevocably altered. Burbank's commission was explicitly for documentation, intended for educational and exhibition purposes, forming a significant part of his uncle's vast collection, much of which eventually found a home at the Newberry Library in Chicago.

Artistic Style and Preferred Media

Elbridge Ayer Burbank's artistic style was predominantly rooted in realism, a direct consequence of his academic training and the documentary nature of his primary mission. He aimed for verisimilitude, seeking to capture the distinct features, attire, and character of his sitters with accuracy. While his European studies in Munich might have exposed him to a more painterly, bravura style, his Native American portraits generally exhibit a more controlled and detailed approach, prioritizing likeness and ethnographic detail.

Burbank worked in several media, including oil paints and watercolors. His oil portraits often possess a solidity and depth, allowing for rich color and texture, particularly in rendering traditional clothing, beadwork, and adornments. However, he became particularly renowned for his skillful use of conte crayon, a hard pastel stick made from a mixture of graphite or charcoal and clay. Conte crayon, often in sanguine (reddish-brown) or black, allowed for fine lines and subtle shading, making it an ideal medium for capturing the nuances of facial features and expressions with a degree of immediacy. Many of his most compelling and intimate portraits were executed in this medium. His style, while realistic, often imbued his subjects with a sense of dignity and quiet strength, avoiding the overt romanticism or dramatic action favored by some of his contemporaries like Frederic Remington or Charles M. Russell, who focused more on the narrative and mythos of the West. Burbank's focus remained steadfastly on the individual.

Encounters and Relationships: Among the People

Burbank's extensive travels brought him into direct contact with a wide array of Native American individuals, including some of the most famous and historically significant figures of the era. His approach often involved spending considerable time within communities, allowing him to build a degree of rapport with his subjects, which was essential for portrait sittings. He is known to have formed a notable friendship with Lorenzo Hubbell, the influential trader at Ganado, Arizona, whose Hubbell Trading Post was a vital center for Navajo and Hopi people. Burbank spent extended periods at the trading post, painting numerous portraits of local individuals.

Perhaps his most famous sitter was Geronimo (Goyaałé), the renowned Apache leader. Burbank painted Geronimo multiple times, and it is reported that Geronimo developed a particular fondness for Burbank, stating he liked him better than any other white man he had met. This personal connection speaks to Burbank's ability to engage with his subjects on a human level, beyond the mere artist-model dynamic. He also painted other prominent leaders such as Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Red Cloud of the Oglala Lakota, Sitting Bull of the Hunkpapa Lakota (though likely from photographs or earlier sketches by others for some posthumous depictions), and Rain-in-the-Face. These encounters were not always straightforward; they occurred against a backdrop of immense cultural upheaval, loss of land, and forced assimilation. Burbank's presence as a white artist documenting these leaders and their people was complex, yet his dedication to the task was unwavering. He also had a notable interaction with the Kiowa artist Silver Horn (Hawgone) at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where Burbank was impressed by Silver Horn's "naturalistic" ledger art and even commissioned a portrait from him.

Representative Works and Notable Subjects

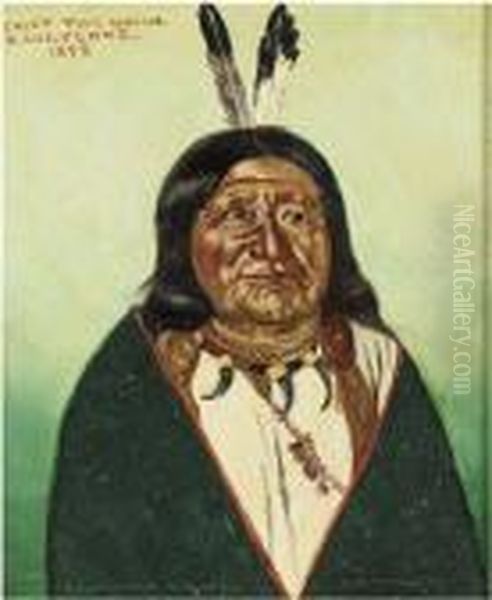

Among the vast corpus of Elbridge Ayer Burbank's work, several portraits stand out due to the prominence of the sitter or the quality of the execution. His portrait of Geronimo is perhaps his most iconic. Having painted the Apache leader on multiple occasions, Burbank captured a sense of the warrior's resilience and enduring spirit, even in captivity. One of these portraits is noted as being the only one Geronimo sat for from life for Burbank.

The portrait of Chief Red Cloud (Makhpiya-Luta) of the Oglala Lakota is another significant work. Red Cloud was a formidable leader who had challenged the U.S. government for years. Burbank's depiction conveys a sense of gravitas and wisdom. Similarly, his portraits of Chief Joseph (Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it) of the Nez Perce capture the dignity and sorrow of a leader who fought valiantly for his people's freedom.

Other important subjects include Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake), though some depictions might have been posthumous or based on photographs given Sitting Bull's death in 1890 and the peak of Burbank's portraiture work following slightly later. Portraits of lesser-known individuals, yet equally important for their representation of diverse tribal affiliations, such as Ah-Che-To-Mah (a Kickapoo chief), Ne-goze-de-tah (an Apache man), and numerous figures from tribes like the Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, Hopi, and Zuni, collectively form a powerful visual archive. Each portrait, whether of a famed leader or an ordinary member of a tribe, was approached with a consistent effort to record individual likeness and cultural attributes. These works, often executed in oil or his characteristic conte crayon, are now held in major collections, serving as invaluable historical documents.

Exhibitions, Collections, and Recognition

Elbridge Ayer Burbank's extensive body of work, particularly his Native American portraits, gained significant recognition during his lifetime and continues to be valued by institutions and collectors. His paintings and drawings were exhibited in various important venues, reflecting the contemporary interest in images of the American West and its indigenous peoples. Notably, his works were shown at the Paris World's Fair and the St. Louis World's Fair (Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904), major international showcases that brought his art to a global audience.

The primary repository for Burbank's Native American portraits became the collection of his uncle, Edward E. Ayer. A substantial portion of this collection, including many of Burbank's pieces, was eventually donated to the Newberry Library in Chicago, where the Edward E. Ayer Collection remains one of the world's foremost resources for the study of Native American history and culture. The Field Museum in Chicago also holds significant works by Burbank, stemming from his uncle's early involvement with that institution.

Furthermore, Burbank's art found its way into other prestigious collections, including the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., which has a long history of ethnographic collection and research. The Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site in Ganado, Arizona, preserves a collection of paintings Burbank created during his extended stays there, offering a specific regional focus within his broader oeuvre. His work is also represented in the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio, among other museums. This widespread institutional presence underscores the historical and artistic importance attributed to his dedicated efforts to document Native American life.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Landscape of the West

Elbridge Ayer Burbank operated within a rich and varied artistic landscape, particularly concerning the depiction of the American West and its Native inhabitants. He was a contemporary of several artists who also focused on these themes, though often with different approaches and artistic goals.

Frederic Remington (1861-1909) and Charles M. Russell (1864-1926) were perhaps the most famous "Western" artists of the era. However, their work often emphasized dramatic narratives, action-packed scenes of cowboys and conflict, and a more romanticized, even mythologized, vision of the West. While they painted Native Americans, it was often within these dynamic, illustrative compositions, contrasting with Burbank's more direct, portrait-focused ethnographic approach.

The Taos Society of Artists, founded in 1915, included painters like Joseph Henry Sharp (1859-1953), E. Irving Couse (1866-1936), Oscar E. Berninghaus (1874-1952), Bert Geer Phillips (1868-1956), and Ernest L. Blumenschein (1874-1960). Sharp, in particular, shared Burbank's dedication to painting Native American portraits with a degree of ethnographic intent, spending many years living and working among the Plains and Pueblo peoples. While Burbank was not a member of this group, his focus on Native subjects paralleled theirs, though the Taos artists often incorporated more modernist influences and a greater emphasis on light and landscape.

Other notable contemporaries include Henry Farny (1847-1916), known for his sympathetic and often tranquil depictions of Native American life, and Charles Schreyvogel (1861-1912), who, like Remington, specialized in dramatic scenes of cavalry and Native American encounters. Photographers like Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) were engaged in a similarly massive undertaking to document Native American life through a different medium, often with a shared sense of urgency to capture what was perceived as a "vanishing race." Burbank's unique contribution lies in the sheer volume of his individual portraits and his consistent, relatively unembellished style. One might also consider the influence of earlier figures like George Catlin (1796-1872) and Karl Bodmer (1809-1893), whose extensive visual records of Native American life in the mid-19th century set a precedent for later artists like Burbank. Even portraitists working in different spheres, such as John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), set a high bar for capturing character, a standard Burbank, in his own way, strove for.

Personal Challenges and Later Years

Despite his significant artistic output and the unique niche he carved for himself, Elbridge Ayer Burbank's personal life was marked by considerable challenges, particularly in his later years. He suffered from periods of mental illness, which led to him spending a significant amount of time, reportedly nearly two decades, in and out of institutions, including a state mental hospital in Napa, California. The exact nature and progression of his illness are not extensively documented in public records, but it undoubtedly impacted his ability to work consistently during these periods.

These personal struggles cast a poignant shadow over a career dedicated to observing and portraying others. The intensity of his travels, the often solitary nature of his work, and the emotional weight of witnessing the profound changes affecting Native American communities may have taken a toll. Regardless of these difficulties, his earlier productivity had already secured his legacy. His life came to a tragic and abrupt end on April 21, 1949, in San Francisco, California. At the age of 90, he was killed in a street accident involving a cable car. He was reportedly struck by the vehicle, a starkly urban end for an artist who had spent so much of his life in the remote landscapes of the American West.

The Burbank Legacy: A Complex Inheritance

Elbridge Ayer Burbank's legacy is multifaceted and invites ongoing consideration. His most undeniable contribution is the sheer volume of his work: over 1200 portraits of Native American individuals from more than 125 tribes. This extensive visual archive provides an invaluable resource for historians, ethnographers, descendants of his subjects, and art historians. His paintings and drawings offer a glimpse into the appearance, attire, and, to some extent, the character of a generation of Native Americans navigating a period of immense cultural pressure and transition. His commitment to direct portraiture, often from life, lends a degree of authenticity to his depictions that is highly valued.

However, Burbank's work is not without its complexities and criticisms from a contemporary perspective. Like many artists and ethnographers of his time, he operated within the prevailing "vanishing race" paradigm, which, while motivating preservation efforts, also tended to frame Native cultures as static or doomed, rather than dynamic and resilient. Some critics have pointed out that his focus was primarily on capturing likeness and ethnographic "types," sometimes at the expense of deeper individual characterization or the subject's own agency in their portrayal. There have also been instances noted where subjects were posed with artifacts or in attire that may not have been entirely accurate to their specific cultural group or personal status, a common practice at the time aimed at creating a more "representative" or visually interesting image for a non-Native audience.

Despite these valid critiques, the historical significance of Burbank's oeuvre remains. His portraits, housed in institutions like the Newberry Library and the Smithsonian, continue to be studied and appreciated. They serve as important historical documents, preserving the visages of individuals whose stories might otherwise be lost to time. His dedication to this singular, monumental task ensures his place in the annals of American Western art, not as a stylist or innovator in the vein of modernism, but as a diligent and prolific chronicler of a people and an era. His work prompts reflection on the role of the artist as documentarian, the ethics of representation, and the enduring power of the human face to convey history and dignity.

Conclusion: An Enduring Visual Record

Elbridge Ayer Burbank's life and art were dedicated to a singular, ambitious vision: to create a lasting visual record of the Native peoples of America during a critical period of their history. Through thousands of portraits in oil, watercolor, and particularly his favored conte crayon, he captured the likenesses of individuals from a multitude of tribes, from renowned leaders like Geronimo and Red Cloud to countless others whose names are less widely known but whose presence contributes to the richness of his archive.

While his approach was shaped by the ethnographic and artistic conventions of his time, and subject to later critiques regarding representation, the sheer scale and dedication of his undertaking are remarkable. His work provides an invaluable resource, offering faces to names and a human dimension to historical narratives. The collections of his art, most notably at the Newberry Library, the Field Museum, and the Smithsonian Institution, stand as a testament to his tireless efforts and the patronage of his uncle, Edward E. Ayer. Burbank's legacy is that of a chronicler, an artist who, with skill and empathy, preserved a gallery of faces that speak to the dignity, resilience, and diversity of Native American life at the turn of the 20th century, ensuring that these individuals would not be forgotten.