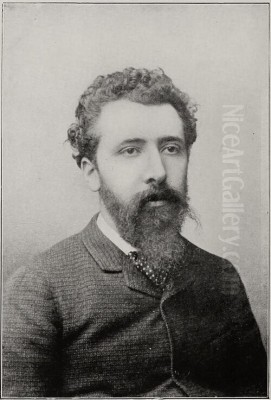

Georges Seurat stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of late 19th-century French art. Born in Paris in 1859 and dying tragically young in 1891, his brief but intensely productive career fundamentally altered the course of painting. Associated primarily with Post-Impressionism, Seurat was the innovator and leading proponent of Neo-Impressionism, a movement grounded in scientific theories of optics and color. His meticulous technique, known as Pointillism or Divisionism, involved applying small, distinct dots of pure color to the canvas, relying on the viewer's eye to blend them optically. This methodical approach marked a significant departure from the spontaneity of Impressionism and laid crucial groundwork for future artistic developments, including Fauvism and Cubism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Georges-Pierre Seurat entered the world in Paris on December 2, 1859, into a family of considerable means. His father, Antoine Chrysostome Seurat, was a legal official, originally from Champagne, while his mother, Ernestine Faivre, was Parisian. This comfortable background provided Seurat with the stability and resources to pursue his artistic inclinations from an early age. He lived with his mother, brother Émile, and sister Marie-Berthe, while his somewhat eccentric father resided separately.

Seurat's formal artistic training began around 1875 at the municipal school of sculpture and drawing, near his family's home. Here, he studied under the sculptor Justin Lequien. A significant early influence was the book "Grammaire des arts du dessin" (Grammar of the Arts of Drawing) by Charles Blanc, published in 1867. Blanc's theories on color and optics, which Seurat studied intently, would profoundly shape his later artistic practice, particularly the concepts of optical mixture and complementary colors.

In 1878, Seurat advanced to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the official French academy of fine arts. He entered the studio of Henri Lehmann, a disciple of the Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. At the École, Seurat received rigorous academic training focused on drawing and composition, emphasizing line and form in the tradition of Ingres. However, Seurat also spent countless hours studying the Old Masters in the Louvre, particularly drawn to the vibrant color and dynamic compositions of artists like Eugène Delacroix. He sought to reconcile the linear precision of Ingres with the expressive colorism of Delacroix.

His formal studies were interrupted in November 1879 when he left the École for a year of compulsory military service. Stationed in Brest, a port city in Brittany, Seurat did not cease his artistic activities. He filled sketchbooks with drawings of seascapes, fellow soldiers, and coastal life, continuing to hone his skills, particularly in capturing tonal values using Conté crayon on textured paper – a medium he would master and utilize throughout his career for preparatory studies.

The Genesis of Neo-Impressionism

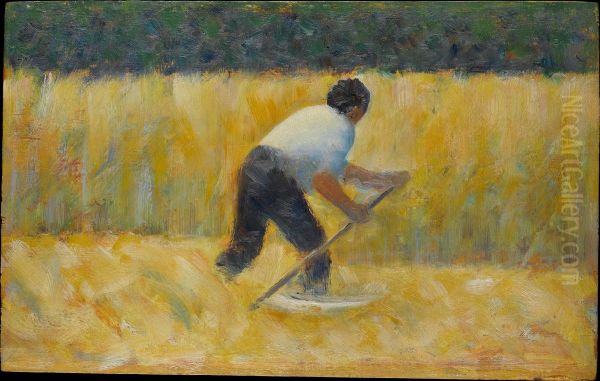

Upon returning to Paris in late 1880, Seurat chose not to return to the formal structure of the École des Beaux-Arts. Instead, he rented a small studio and embarked on an intensive period of self-directed study and experimentation. He dedicated himself to mastering the art of black-and-white drawing, producing a remarkable series of Conté crayon studies that explored light, shadow, and form with subtle gradations of tone. These drawings often depicted scenes of urban life, workers, and suburban landscapes, demonstrating his keen observational skills.

During the early 1880s, Seurat became increasingly fascinated by scientific theories related to color, optics, and perception. He delved deeper into the writings of Charles Blanc, and also studied the work of scientists like Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood, and Charles Henry. Chevreul's "The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors" (1839), which analyzed simultaneous contrast (how adjacent colors influence each other's perception), was particularly influential. Ogden Rood's "Modern Chromatics" (1879) discussed the differences between additive light mixture (colored light beams combining to create lighter, brighter colors) and subtractive pigment mixture (paints mixing to create duller colors).

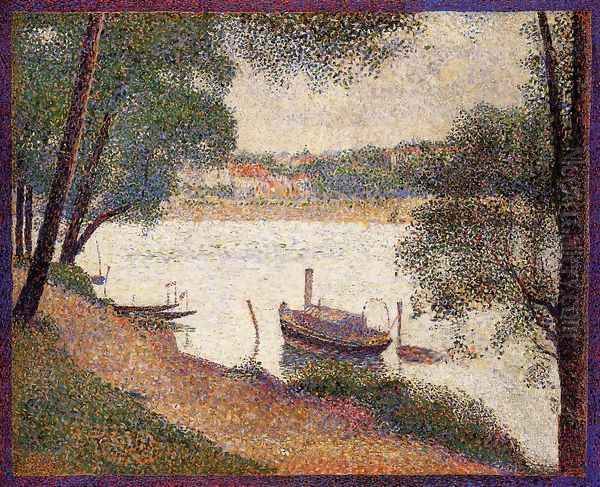

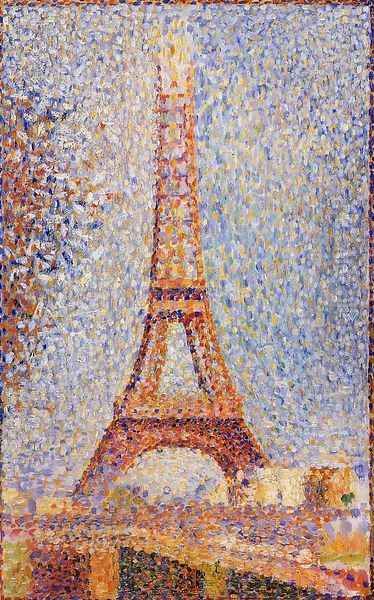

Seurat sought to apply these scientific principles directly to painting. He believed that by juxtaposing small dots or strokes of pure, unmixed color on the canvas, the colors would mix optically in the viewer's eye (additive mixture), resulting in greater luminosity and vibrancy than could be achieved by mixing pigments on the palette (subtractive mixture). This systematic approach, which aimed for a more objective and scientifically grounded representation of light and color, formed the core of Neo-Impressionism, a term coined by the critic Félix Fénéon in 1886.

Pointillism: A Methodical Revolution

The technique Seurat developed is most commonly known as Pointillism (from the French word "point," meaning dot), although Seurat himself preferred the term Divisionism or Chromo-luminarism. It involved the meticulous application of small, regular touches of unmixed color directly onto the canvas. Complementary colors (like red and green, or blue and orange) were often placed side-by-side to enhance each other's intensity through simultaneous contrast, a principle derived directly from Chevreul's theories.

This method was laborious and required immense patience and discipline. Unlike the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who sought to capture fleeting moments and atmospheric effects with rapid brushwork, Seurat constructed his paintings slowly and deliberately. He would often create numerous preparatory studies in oil and Conté crayon, carefully planning the composition and color relationships before beginning the final canvas.

The resulting paintings possessed a unique visual quality. From a distance, the individual dots of color coalesce in the viewer's eye, creating shimmering, vibrant surfaces that effectively convey light and atmosphere. Up close, the structure of the painting is revealed as a complex tapestry of distinct color points. This technique aimed for a harmony and order that Seurat felt was lacking in the more intuitive approach of the Impressionists.

Major Work: Bathers at Asnières

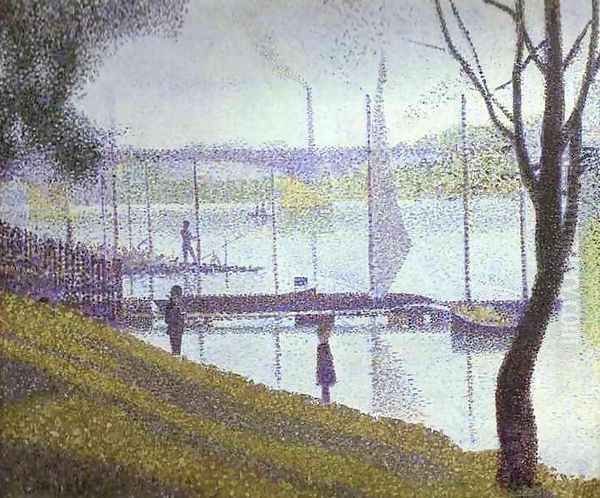

Seurat's first major large-scale painting, Bathers at Asnières (Une Baignade, Asnières), completed in 1884, marked his public debut as an ambitious innovator. Measuring approximately two by three meters, the painting depicts working-class men and boys relaxing on the banks of the Seine River in Asnières, a suburb northwest of Paris. Across the river, the factories and smokestacks of Clichy are visible, grounding the scene in a specific industrial locale.

The painting showcases Seurat's early exploration of Divisionist principles, although the technique is not yet fully developed Pointillism. While there are areas where small dots of color are used, particularly in the water and grass, much of the painting employs broader, crisscrossing brushstrokes reminiscent of Impressionism. However, the careful composition, the statuesque quality of the figures, and the deliberate study of light and color clearly signal Seurat's departure from Impressionist spontaneity.

Seurat submitted Bathers at Asnières to the official Paris Salon of 1884, but it was rejected by the jury. This rejection was a significant turning point. Disillusioned with the conservative Salon system, Seurat, along with other artists whose work had been refused, including Paul Signac and Odilon Redon, founded the Société des Artistes Indépendants (Society of Independent Artists). This new organization established an annual unjuried exhibition, providing a crucial venue for avant-garde artists to show their work freely. Bathers at Asnières was displayed at the first Indépendants exhibition in May-June 1884, where it attracted considerable attention and established Seurat as a leader among the younger generation of artists.

Masterpiece: A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

Following Bathers, Seurat immediately began work on what would become his most famous and defining masterpiece: A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte). This monumental canvas, similar in scale to Bathers, occupied him for two years, from 1884 to 1886. It depicts Parisians from various social classes enjoying a sunny afternoon on La Grande Jatte, an island park in the Seine near Asnières, directly across the river from the scene in Bathers.

La Grande Jatte represents the full maturation of Seurat's Pointillist technique. The entire surface is composed of meticulously applied tiny dots of contrasting and complementary colors. Seurat created numerous preparatory oil sketches and Conté crayon drawings, studying individual figures, compositional arrangements, and color harmonies with scientific precision. He even returned to the painting after its initial exhibition to rework sections and refine the Pointillist application, adding a painted border of dots to enhance the optical effects according to Charles Henry's theories on the emotional properties of lines and colors.

The painting presents a complex social tableau. Stiff, formally dressed bourgeois figures mingle with more relaxed working-class individuals, children play, pets roam, and boats glide on the river. The figures are rendered with a distinct, almost geometric stylization, appearing frozen in time like figures in an ancient Egyptian frieze or a Piero della Francesca fresco. This static, timeless quality contrasts sharply with the Impressionist focus on capturing the ephemeral.

La Grande Jatte was exhibited at the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition in 1886, alongside works by Camille Pissarro (who had temporarily adopted Pointillism under Seurat's influence) and Paul Signac. It caused a sensation, provoking both admiration and ridicule. Critics were divided; some praised its innovative technique and monumental ambition, while others found it cold, mechanical, and overly systematic, famously deriding the dots as "confetti" or "fly specks." Regardless of the mixed reception, the painting cemented Seurat's position as the leader of Neo-Impressionism and became an icon of late 19th-century art.

Later Works and Thematic Concerns

In the years following La Grande Jatte, Seurat continued to refine his technique and explore new subjects, although his output was limited by his painstaking method and tragically short life. He produced several other major figure compositions depicting scenes of Parisian entertainment and nightlife, including Parade de cirque (Circus Sideshow, 1887-88), Le Chahut (1889-90), and his final, unfinished masterpiece, Le Cirque (The Circus, 1890-91). These works often employed artificial gaslight, allowing Seurat to experiment with complex color harmonies and the expressive potential of line and direction, influenced by Charles Henry's theories.

Alongside these urban scenes, Seurat also produced a series of serene and luminous seascapes during summers spent on the Normandy coast at locations like Grandcamp, Honfleur, and Gravelines. Works such as The Channel of Gravelines, Evening (1890) demonstrate his mastery of applying Pointillism to capture the subtle effects of light and atmosphere on water and sky. These landscapes are often characterized by simplified forms, horizontal compositions, and a sense of calm and order, contrasting with the dynamism of his circus pictures.

Throughout his work, Seurat maintained a consistent artistic vision. He sought to imbue modern subjects – leisure activities, urban landscapes, popular entertainment – with a sense of timeless grandeur and formal structure, drawing inspiration from classical art while employing a radically modern, scientifically informed technique. His compositions are always carefully balanced, often employing geometric principles like the Golden Section, reflecting his desire for harmony and intellectual rigor in art.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Seurat's methodical approach and distinct style set him apart from many of his contemporaries, yet he was deeply engaged with the artistic currents of his time. His closest artistic ally was Paul Signac, who met Seurat in 1884 at the founding of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. Signac quickly adopted Seurat's Divisionist technique and became its most ardent champion and theorist, continuing to practice and promote Neo-Impressionism long after Seurat's death. They shared studios, discussed theories, and exhibited together.

The elder Impressionist Camille Pissarro was briefly but significantly influenced by Seurat. Around 1885, impressed by Seurat's innovations, Pissarro adopted the Pointillist technique for several years, much to the consternation of some of his former Impressionist colleagues like Edgar Degas. Although Pissarro eventually returned to a more fluid style, his Neo-Impressionist period demonstrates the impact Seurat had even on established masters.

Seurat's relationship with the broader Impressionist movement was complex. While he exhibited at their final group show, his emphasis on structure, permanence, and scientific method contrasted with the Impressionist focus on capturing fleeting moments and sensory perception, as seen in the works of Monet and Renoir. Seurat aimed for a synthesis, combining the Impressionists' interest in light and contemporary life with a classical sense of order and stability, looking back to masters like Ingres and Piero della Francesca.

His work also resonated with other Post-Impressionist artists who were seeking new directions beyond Impressionism. Vincent van Gogh, who was in Paris during the rise of Neo-Impressionism, experimented with dotted brushwork and vibrant color contrasts, clearly influenced by Seurat and Signac. While Paul Gauguin pursued a different path towards Synthetism, Seurat's emphasis on pure color and formal structure contributed to the broader Post-Impressionist exploration of art's expressive potential. There are also conceptual links to Paul Cézanne's search for underlying structure and geometric form in nature, although their methods differed greatly.

Personality and Private Life

Contrasting with his revolutionary art, Seurat's personal life was marked by reserve and secrecy. He was known among his friends and colleagues as introverted, methodical, and intensely dedicated to his work. He rarely socialized extensively, preferring the solitude of his studio. His disciplined and scientific approach to painting seemed to mirror a controlled and private personality.

This secrecy extended to his personal relationships. For several years, Seurat maintained a relationship with Madeleine Knobloch, a young artist's model. They lived together in his studio on the Boulevard de Clichy, near the bustling entertainment district of Montmartre and the newly opened Moulin Rouge. In February 1890, Madeleine gave birth to their son, Pierre-Georges Seurat. Astonishingly, Seurat kept his relationship and his son a secret from almost everyone, including his own mother and closest friends like Signac. It was only two days before his death that he formally introduced Madeleine and Pierre-Georges to his mother.

His family background was affluent, yet Seurat lived a relatively modest and intensely focused life, channeling his energies almost entirely into his demanding artistic practice. His brief military service seems to have been the only significant interruption to his dedicated pursuit of art. This intense focus and perhaps the physical demands of his meticulous technique may have contributed to his relatively frail health.

Controversies and Critical Reception

Seurat's art was controversial from the moment it appeared. His Pointillist technique, while admired by some for its scientific basis and visual effects, was frequently criticized by others. Conservative critics dismissed it as overly systematic, lacking emotion, and visually jarring. The comparison to "fly specks" or "confetti" became a common refrain among detractors. Even some avant-garde figures found his approach too rigid.

The rejection of Bathers at Asnières by the Salon highlighted the conflict between Seurat's innovative vision and the established art institutions. His subsequent co-founding of the Société des Artistes Indépendants was a direct challenge to the Salon's authority and a crucial step in creating alternative venues for modern art.

The intellectual and scientific underpinnings of his work also sparked debate. While Seurat and his supporters, like Félix Fénéon and Paul Signac, emphasized the rational and objective basis of Neo-Impressionism, critics argued that this scientific approach led to cold, impersonal, and overly calculated art, devoid of the spontaneity and passion valued in other forms of painting. The static, almost frozen quality of his figures in works like La Grande Jatte was often interpreted as a lack of vitality or emotional depth.

Despite the controversies, Seurat attracted a small but dedicated group of followers, including Signac, Pissarro (for a time), Henri-Edmond Cross, and Maximilien Luce, who formed the core of the Neo-Impressionist movement. His work was championed by insightful critics like Fénéon, who recognized its radical importance.

Untimely Death and Lasting Legacy

In March 1891, while exhibiting his final, unfinished painting The Circus at the Salon des Indépendants, Georges Seurat fell ill. His condition rapidly deteriorated, and he died on March 29, 1891, at the tragically young age of 31. The cause of death is uncertain but often attributed to a form of meningitis, diphtheria, or infectious angina. His death shocked the Parisian art world. Tragically, his infant son, Pierre-Georges, died from the same illness just two weeks later. Madeleine Knobloch inherited his studio contents.

Despite his short career, spanning little more than a decade, Seurat's impact on the development of modern art was profound and enduring. Neo-Impressionism, though practiced by a relatively small group, introduced a new way of thinking about color and form that resonated widely. His systematic application of color theory and his exploration of optical effects directly influenced the next generation of avant-garde artists.

The Fauves, including Henri Matisse and André Derain, were inspired by Seurat's use of pure, intense color, even as they moved away from the Pointillist technique towards broader, more expressive brushwork. The structured compositions and geometric stylization in Seurat's work also provided a crucial precedent for the development of Cubism by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who sought to analyze and reconstruct form in a similarly rigorous manner.

Today, Georges Seurat is recognized as one of the most important figures of Post-Impressionism and a key pioneer of modern art. His major works, particularly A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, are celebrated icons held in major museum collections worldwide. His unique synthesis of art and science, his innovative Pointillist technique, and his quest for harmony and order continue to fascinate artists, historians, and the public alike. He demonstrated that a methodical, almost scientific approach could produce art of great beauty, complexity, and lasting significance, forever changing the possibilities of painting.