Eduard Charlemont stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century European art. Born in Vienna, the heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Charlemont carved a distinguished career primarily in Paris, becoming renowned for his meticulously detailed and evocative Orientalist paintings, as well as impressive mural work. His art, characterized by a brilliant handling of light, rich color palettes, and a keen eye for ethnographic detail, captured the European fascination with the "Orient" while also reflecting the academic traditions of his training. This exploration delves into the life, artistic achievements, stylistic nuances, and the broader context of Eduard Charlemont's contributions to art history.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Vienna

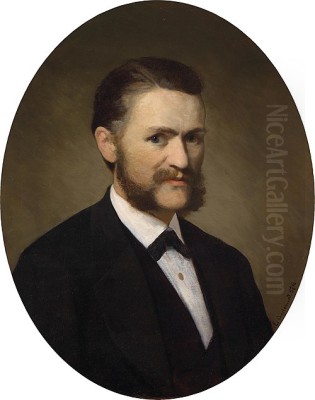

Eduard Charlemont was born in Vienna on March 2, 1848, into a family with artistic inclinations. His father, Matthias Adolf Charlemont, was a painter specializing in portrait miniatures, providing young Eduard with an early immersion in the world of art. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured his nascent talent. His younger brother, Hugo Charlemont, would also become a notable painter, known for his still lifes and landscapes, indicating a strong artistic current within the family.

Recognizing his son's potential, Matthias encouraged Eduard's formal artistic education. Eduard enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien), one of Europe's oldest and most respected art schools. Here, he would have been steeped in the rigorous academic tradition, focusing on drawing from classical sculpture, life drawing, and the study of Old Masters. The Viennese Academy at this time was a bastion of historical painting and academic realism, a style that emphasized technical skill, anatomical accuracy, and carefully constructed compositions. Figures like Carl Rahl, a prominent historical painter and professor at the Academy, would have been influential, though Rahl died when Charlemont was still young. The prevailing artistic atmosphere in Vienna was one of grandeur, heavily influenced by the Ringstrasse development, which saw the construction of opulent public buildings adorned with historical and allegorical art.

Charlemont proved to be a prodigious talent. As early as the age of 15, in 1863, he exhibited his first works at the Academy, a remarkable achievement for such a young artist. This early success hinted at the promising career that lay ahead. During this period, he also reportedly took on a teaching role, instructing drawing at a girls' school, which demonstrates a maturity and command of his craft even at a young age. His early works, though less documented than his later Parisian output, would have likely reflected the academic training he received, possibly focusing on portraits, genre scenes, or historical subjects popular in Vienna at the time.

The Parisian Sojourn and Rise to Prominence

While Vienna provided his foundational training, it was Paris that became the main stage for Eduard Charlemont's artistic career. He moved to the French capital, the undisputed center of the art world in the 19th century, and resided there for approximately thirty years. This move was a common trajectory for ambitious artists from across Europe and America, who sought the vibrant artistic environment, the prestigious exhibition venues, and the potential for international recognition that Paris offered.

In Paris, Charlemont quickly made a name for himself. He became a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was the most important art event in the Western world. Success at the Salon could make an artist's career, leading to critical acclaim, lucrative commissions, and sales to wealthy patrons and public collections. Charlemont not only exhibited but also achieved significant recognition, winning multiple first-class medals at the Salon. This was a testament to his technical skill and the appeal of his chosen subjects, particularly his Orientalist scenes.

The Paris Salon during Charlemont's active years was dominated by academic art, though Impressionism was beginning to challenge its hegemony. Artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Alexandre Cabanel, and Jean-Léon Gérôme were titans of the Salon, producing highly finished paintings often based on mythological, historical, or exotic themes. Charlemont's work, with its meticulous detail and polished surfaces, aligned well with the prevailing tastes of the Salon juries and the art-buying public. His success there solidified his reputation as a leading painter of his generation, particularly within the Orientalist genre.

The Allure of the Orient: Charlemont's Orientalist Vision

Eduard Charlemont is best known for his contributions to Orientalism, an artistic and cultural movement that depicted scenes and subjects from the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia, often filtered through a romanticized and exoticizing European lens. The 19th century saw a surge in European interest in these regions, fueled by colonialism, travel, archaeology, and literature. Artists sought to capture what they perceived as the vibrant colors, exotic customs, and mysterious allure of these distant lands.

Charlemont's Orientalist paintings are characterized by their detailed realism, rich textures, and dramatic use of light and shadow. He often depicted scenes of daily life, marketplaces, interiors of mosques or palaces, and figures in traditional attire. Unlike some Orientalists who relied heavily on imagination or studio props, Charlemont's work suggests a keen observation, possibly informed by travel or extensive research through photographs and artifacts, though specific details of his travels to the "Orient" are not extensively documented.

His approach to Orientalism was less about grand historical narratives and more focused on intimate, atmospheric scenes. He had a particular talent for rendering the play of light on different surfaces – gleaming metalwork, rich textiles, sun-drenched courtyards, and shadowy interiors. This mastery of light, combined with his vibrant color palette, brought his scenes to life, imbuing them with a sense of immediacy and sensory richness. While his work partook in the general European fascination with the exotic, some critics have noted that his Austrian background perhaps lent a unique, sometimes described as "overheated," quality to his Orientalism, allowing him to sidestep some of the more common clichés of the genre. He shared this thematic interest with other Austrian Orientalists like Ludwig Deutsch and Rudolf Ernst, who were also highly successful in Paris, and French masters of the genre such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose meticulous detail and ethnographic interest set a high bar. Earlier Romantic painters like Eugène Delacroix had paved the way with their passionate depictions of North Africa, and even Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, with works like "La Grande Odalisque," contributed to the exotic female nude trope within Orientalism.

Masterpiece: "The Moorish Chief"

Among Charlemont's extensive oeuvre, one painting stands out as his most celebrated and iconic work: "The Moorish Chief." Originally exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1878 under the title "Le Gardien du Sérail" (The Guardian of the Seraglio), it later became widely known as "The Moorish Chief" or "The Moorish Nobleman."

The painting depicts a formidable, dark-skinned figure, presumably a Moorish warrior or chieftain, standing guard. He is clad in opulent, richly detailed attire, including a white, flowing robe and an elaborate turban, and armed with a gleaming scimitar. The figure stands in a sumptuously decorated interior, likely inspired by the architecture of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, or similar Moorish palaces. The intricate tilework, carved stucco, and ornate archways are rendered with Charlemont's characteristic precision. The chief's stern, watchful expression and powerful stance convey a sense of authority and protective vigilance, hinting at the unseen world of the seraglio he guards.

"The Moorish Chief" is a tour de force of academic technique and Orientalist exoticism. Charlemont's skill in rendering textures – the sheen of the silk, the glint of metal, the coolness of the tiles – is exceptional. The play of light and shadow is masterfully handled, highlighting the central figure and creating a dramatic, almost theatrical atmosphere. The painting was highly acclaimed at the Salon and was eventually acquired by the prominent American collector John G. Johnson, and is now part of the collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Its enduring popularity speaks to its compelling subject matter and Charlemont's artistic prowess. The work encapsulates many of the key elements of successful Orientalist painting: an exotic setting, richly detailed costumes and props, a sense of mystery, and a technically brilliant execution. It can be compared in its impact and meticulousness to works by Gérôme or Deutsch, who also specialized in depicting solitary, imposing figures in elaborate Eastern settings.

Monumental Art: The Burgtheater Murals

Beyond his easel paintings, Eduard Charlemont also undertook significant commissions for monumental decorative works, most notably the murals for the Burgtheater (Austrian National Theatre) in Vienna. This prestigious commission underscores his high standing in the Viennese art world, even while he was primarily based in Paris. The new Burgtheater building on the Ringstrasse, designed by Gottfried Semper and Karl von Hasenauer, was completed in 1888, and its interior decoration involved many of the leading artists of the era.

Charlemont was tasked with creating three large ceiling paintings for one of the grand staircases of the theater. These murals, completed around 1894-1895, are impressive in scale, reportedly totaling some 55 meters in length. The subjects of these murals were likely allegorical or historical, in keeping with the decorative programs of such grand public buildings. Creating works of this magnitude required not only artistic skill but also considerable logistical and compositional ability. The tradition of large-scale decorative painting was strong in Vienna, exemplified by the work of Hans Makart, whose opulent and dramatic historical canvases and decorative schemes had a profound impact on the city's artistic life in the decades preceding Charlemont's mural commission. While Makart's style was perhaps more flamboyant, Charlemont would have brought his characteristic precision and rich coloring to these monumental works. Other artists involved in the Burgtheater's decoration included the young Gustav Klimt and his brother Ernst Klimt, along with Franz Matsch, who together formed the "Künstler-Compagnie" (Artists' Company) and decorated other parts of the theater. Charlemont's contribution placed him among the elite artists entrusted with adorning one of Vienna's most important cultural institutions.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Influences

Eduard Charlemont's artistic style was firmly rooted in 19th-century academicism, emphasizing meticulous draftsmanship, smooth brushwork, and a highly polished finish. His compositions were carefully planned and executed, with a strong sense of balance and clarity.

Light and Color: A hallmark of Charlemont's style was his exceptional handling of light and color. He was adept at capturing the subtle nuances of light, whether it was the bright sunlight of an outdoor scene or the filtered light of an interior. His colors were rich and vibrant, contributing to the exotic and often sensual appeal of his Orientalist works. He used chiaroscuro effectively to model forms and create dramatic emphasis.

Detail and Texture: Charlemont's paintings are characterized by an extraordinary level of detail. He paid close attention to the rendering of fabrics, architectural elements, weaponry, and other accoutrements, giving his scenes a strong sense of verisimilitude, even when the subject matter was romanticized. This meticulousness aligns him with other academic Orientalists like Gérôme and Deutsch, who were also praised for their ethnographic accuracy (or at least, the appearance thereof).

Genre and Subject Matter: While Orientalist themes dominated his most famous works, Charlemont was a versatile artist. He also painted portraits, genre scenes (depicting everyday life), and, as noted, large-scale murals. His portraits would have likely displayed the same technical polish and attention to likeness as his other works. His genre scenes, though less known, would have provided another outlet for his observational skills.

Influences: Charlemont's primary influence was the academic tradition of the Vienna Academy and the Paris Salon. He would have studied the Old Masters, particularly those renowned for their realism and handling of light, such as the Dutch Golden Age painters. Within the Orientalist genre, he was part of a well-established tradition that included earlier figures like Delacroix and Ingres, and contemporaries such as Gérôme, Deutsch, Rudolf Ernst, the British painter John Frederick Lewis (known for his incredibly detailed watercolors and oils of Cairo life), and the American Frederick Arthur Bridgman. Each of these artists brought their own interpretation to Orientalist themes, but they shared a common interest in exotic subject matter and often a high degree of technical finish. The Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy, a contemporary who also achieved great fame in Paris with his dramatic genre and historical scenes, shared a similar commitment to realism and powerful storytelling, though his subjects were generally European.

Charlemont in the Context of His Time

Eduard Charlemont's career spanned a period of significant change in the art world. He matured as an artist when academic art reigned supreme, but he also witnessed the rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Art Nouveau (Jugendstil in Vienna). While Charlemont remained largely faithful to the academic tradition, his work was not created in a vacuum.

In Vienna, the late 19th century saw the dominance of Historicism, particularly in architecture and the decorative arts, as exemplified by the Ringstrasse. Hans Makart was the leading figure of this era, his influence pervasive. Towards the end of Charlemont's life, the Vienna Secession, led by artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann, emerged as a radical challenge to the conservative art establishment, advocating for a new, modern Austrian art. Charlemont, with his academic style, represented the tradition against which these younger artists were rebelling, though his international success and mural work for the Burgtheater ensured his continued relevance.

In Paris, the Salon system, while still powerful, was facing increasing criticism and competition from independent exhibitions. The Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, had already established themselves as a significant force by the time Charlemont was at the height of his Salon career. While Charlemont's detailed realism was stylistically distant from Impressionism's concern with fleeting light and subjective perception, the public's appetite for well-crafted, narrative, and exotic paintings remained strong, ensuring continued success for artists like him.

His Orientalist works catered to a widespread European fascination with cultures perceived as exotic and "other." This fascination was complex, often intertwined with colonial ambitions and stereotypical representations. However, for many artists and viewers, these subjects also offered an escape from the mundane, a realm of fantasy, beauty, and adventure. Charlemont's paintings, with their technical brilliance and evocative power, were highly effective in satisfying this demand.

Later Years and Legacy

Eduard Charlemont continued to paint and exhibit throughout his career. He received further accolades, including a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1889, a mark of high international esteem. After his long and successful career, much of it spent in Paris, Eduard Charlemont eventually returned to his native Vienna. He passed away in Vienna on February 26, 1906.

His legacy is primarily tied to his Orientalist paintings, particularly "The Moorish Chief," which remains a popular and frequently reproduced image. His works are held in various public and private collections, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art and museums in Austria. As an artist, he exemplified the high technical standards of 19th-century academic painting. His ability to create vivid, atmospheric scenes filled with intricate detail and rich color secured his reputation.

While the Orientalist genre has been subject to post-colonial critique for its often stereotypical and romanticized depictions, the artistic skill and historical significance of painters like Charlemont are undeniable. His work provides valuable insight into the tastes, interests, and cultural attitudes of his time. Furthermore, his murals in the Burgtheater stand as a lasting contribution to Vienna's rich artistic heritage. His brother, Hugo Charlemont (1850-1939), also enjoyed a long and respected career, further cementing the Charlemont name in Austrian art history. Other family members, including Hugo's daughter Lilly Charlemont, also pursued artistic careers.

Eduard Charlemont's art continues to be appreciated by collectors and art enthusiasts for its beauty, craftsmanship, and evocative power. He remains a significant representative of the academic and Orientalist traditions in 19th-century European art, a Viennese talent who found international acclaim on the grand stage of Paris. His dedication to his craft and his ability to transport viewers to distant, imagined worlds ensure his enduring place in the annals of art history.