William Langson Lathrop stands as a pivotal figure in American art history, celebrated not only for his evocative landscape paintings but also as the foundational spirit behind the influential New Hope Art Colony. An artist whose career gracefully transitioned from the muted tones of Tonalism to the brighter palette of Impressionism, Lathrop's gentle demeanor and dedication to his craft earned him the respect of his peers and the admiration of subsequent generations. His life and work offer a compelling narrative of artistic evolution, community building, and a profound connection to the American landscape, particularly the rolling hills and river valleys of Pennsylvania.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Born on March 29, 1859, in Warren, Illinois, William Langson Lathrop's formative years were spent far from the established art centers of the East Coast. Raised on a farm in Painesville, Ohio, the rural environment likely instilled in him a deep appreciation for nature that would later define his artistic output. This connection to the land, experienced through the rhythms of agricultural life, provided a foundation of observation and sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere.

In the late 1870s, seeking to forge a career in the arts, Lathrop moved to New York City. Like many aspiring artists of the time, he initially turned to illustration and etching to support himself. While this work provided practical experience in composition and line, it offered meager financial rewards and perhaps limited artistic satisfaction for a painter drawn to the subtleties of landscape. This period, however, was crucial for immersing him in the city's burgeoning art scene and likely exposed him to the prevailing artistic currents of the day.

European Sojourn and Tonalist Influences

A significant turning point in Lathrop's artistic development came with his travels to Europe in the mid-1880s, specifically around 1886. This period abroad was essential for many American artists seeking to refine their skills and absorb contemporary European trends. Lathrop encountered the burgeoning Impressionist movement, which was revolutionizing the way artists perceived and depicted light and color. However, his immediate stylistic direction was perhaps more significantly shaped by his exposure to Tonalism, partly through the influence of fellow American artist Henry Ward Ranger, whom he met abroad.

Tonalism, an American art movement that flourished from the 1880s into the early 20th century, emphasized mood, atmosphere, and a limited, often darker, palette over objective representation. Artists like George Inness, Dwight Tryon, and James McNeill Whistler were key proponents, seeking to evoke spiritual or poetic feelings through subtle gradations of tone and soft-edged forms. Ranger, who Lathrop encountered, was himself a leading figure in Tonalism, and his work likely resonated with Lathrop's own sensibilities, encouraging him to explore this more introspective approach to landscape painting upon his return to the United States.

Establishing a Career: Recognition and Transition

Returning to America, Lathrop began to synthesize his experiences. He focused increasingly on landscape painting, initially working within the Tonalist aesthetic he had begun to explore. His dedication started yielding results in the late 1890s. A major breakthrough occurred when he won the prestigious William T. Evans Prize from the New York Watercolor Club for one of his watercolor landscapes. This award provided significant recognition and validation within the competitive New York art world.

Shortly thereafter, Lathrop held his first solo exhibition, a critical step in establishing his professional standing. These successes marked his arrival as a serious contender in the American art scene. His early works from this period often displayed the hallmarks of Tonalism: quiet, contemplative scenes rendered in harmonious, subdued colors, focusing on the evocative power of twilight or misty conditions. They showcased his sensitivity to atmospheric effects and his ability to imbue a landscape with a palpable sense of mood.

The Genesis of the New Hope Art Colony

The year 1899 proved monumental not just for Lathrop's personal life but for the course of American regional art. Seeking a quieter, more rural environment conducive to his landscape painting, Lathrop, along with his wife Annie, moved from New York City to the small town of New Hope, Pennsylvania. Situated along the scenic Delaware River, the area offered picturesque rolling hills, canals, and charming villages – ideal subjects for a landscape painter. They purchased a property known as Phillips Mill, an old grist mill complex that would become the heart of a thriving artistic community.

Lathrop's arrival marked the beginning of the New Hope Art Colony. He wasn't merely seeking solitude; he possessed a natural ability to attract and nurture talent. His presence, combined with the area's beauty and relative proximity to New York and Philadelphia, began to draw other artists. Lathrop's vision wasn't one of imposing a specific style but rather fostering a supportive environment where artists could develop their individual approaches to depicting the local landscape. Phillips Mill became a gathering place, a studio, and eventually, a center for exhibitions and social life within the colony.

Leadership and Life at Phillips Mill

Lathrop quickly became the informal leader and guiding spirit of the burgeoning colony, often referred to affectionately as its "dean." His gentle nature, combined with his established reputation, made him a respected mentor figure. He began offering outdoor painting classes, attracting students eager to learn his approach to landscape. These classes, often held along the Delaware Canal towpath, led to his students sometimes being referred to as the "Towpath Group."

Life at Phillips Mill was characterized by a blend of serious artistic endeavor and congenial social interaction. Lathrop and his wife hosted gatherings, fostering a sense of community among the artists. He encouraged camaraderie and mutual support, creating an atmosphere where ideas could be exchanged freely. His leadership was subtle yet profound, based on example and encouragement rather than rigid doctrine. He actively promoted the work of his fellow colonists, helping them gain exhibition opportunities and recognition.

The Rise of Pennsylvania Impressionism

While Lathrop's early work leaned towards Tonalism, the environment of New Hope and the influx of other artists, many exploring Impressionist techniques, influenced his own stylistic evolution and contributed to the development of a distinct regional style: Pennsylvania Impressionism, also known as the New Hope School. This style, while rooted in the principles of French Impressionism – capturing fleeting moments of light and color, often painting en plein air – developed unique characteristics.

Pennsylvania Impressionism is often characterized by a bolder, more vigorous brushstroke than its French counterpart, a strong sense of underlying structure and form in the landscape, and a focus on the specific qualities of the Delaware Valley scenery through all seasons. While artists like Claude Monet might dissolve form in light, the New Hope painters often retained a greater sense of solidity and realism. Snow scenes, capturing the stark beauty and subtle light of winter, became a particularly notable subject for many artists in the group, including Lathrop himself, though perhaps most famously associated with Edward Redfield.

Lathrop's Mature Style: Embracing Impressionism

Over time, Lathrop's own palette brightened considerably, moving away from the somber tones of his earlier Tonalist phase. He embraced the Impressionist emphasis on capturing the effects of natural light, using freer, more visible brushwork to convey the vibrancy of the landscape. However, his work often retained a sense of tranquility and structural integrity, reflecting perhaps his Tonalist roots and his deep, contemplative connection to nature.

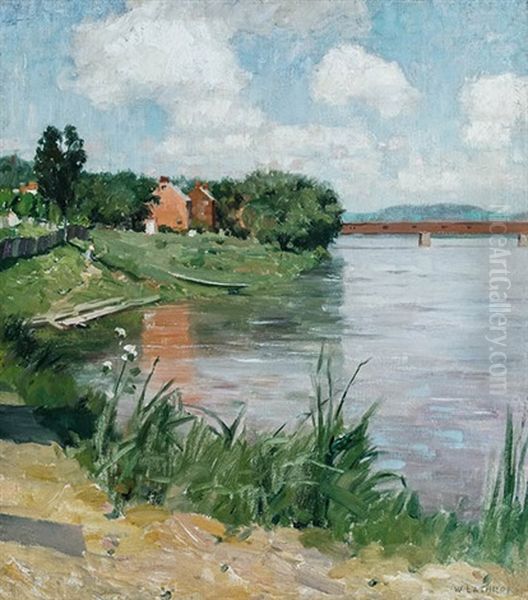

His paintings from this mature period depict the farms, rivers, and hills around New Hope with warmth and affection. He masterfully captured the changing seasons, from the lush greens of summer to the golden hues of autumn and the crisp light of winter. Works like The Delaware Valley (sometimes titled Along the Delaware) exemplify this phase, showcasing his ability to render expansive views with a combination of atmospheric sensitivity and robust composition. The brushwork is active yet controlled, defining forms while simultaneously conveying the shimmer of light across the scene. Another significant work, A Pennsylvania Farm, captures the rustic charm and enduring presence of agrarian life within the landscape he loved.

A Constellation of Artists: The New Hope Circle

Lathrop was the central figure, but the New Hope Art Colony thrived because of the diverse talents it attracted. His presence acted as a magnet, drawing artists who would become major figures in American art. Among the earliest and most prominent was Edward Redfield, known for his large, vigorous, and often snow-covered landscapes, painted directly from nature in a single session (alla prima). Redfield and Lathrop, while stylistically distinct, were foundational pillars of the colony.

Daniel Garber arrived shortly after Redfield, developing a style characterized by a more decorative quality, often featuring intricate patterns of light filtered through foliage, and a higher-keyed, luminous palette. Robert Spencer became known for his depictions of the mills and tenements of the working-class sections of New Hope and nearby Lambertville, offering a different perspective on the local scene compared to the more purely pastoral views of Lathrop or Redfield.

Other significant artists associated with the colony during its flourishing period included Charles Rosen, initially known for powerful winter landscapes similar to Redfield's before shifting towards Modernism; Walter Elmer Schofield, another painter known for his robust, direct approach to landscape; Rae Sloan Bredin, whose work often featured figures, particularly women and children, in garden settings, rendered with a gentle lyricism; and Morgan Colt, a multi-talented figure who was not only a painter but also an architect and craftsman. Later figures like John F. Folinsbee continued the tradition of landscape painting in the area. This group, diverse in their individual styles yet united by their focus on the regional landscape and often by Impressionist techniques, collectively established New Hope as a major center for American art.

National Recognition and Broader Influence

Lathrop's contributions were recognized on a national level. He was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1902 and a full Academician in 1907, prestigious honors signifying his standing among America's leading artists. His work was consistently included in major national exhibitions, and he frequently served on exhibition juries, further shaping the artistic tastes of the time.

His reputation was solidified by awards such as the Gold Medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, a major international event showcasing achievements in arts and industry. His paintings entered the collections of prominent museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., ensuring their accessibility to future generations. Lathrop's success, alongside that of Redfield, Garber, and others, brought national attention to the New Hope School and cemented Pennsylvania Impressionism as a significant movement within the broader context of American Impressionism, which included artists like Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, and his friend John Twachtman, who shared similar interests in capturing the American landscape with nuanced light and color.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Lathrop remained deeply connected to New Hope and Phillips Mill for nearly four decades. He continued to paint actively into his later years, his love for the landscape undiminished. A testament to his enduring passion is the anecdote surrounding his final days. In September 1938, while visiting Montauk, Long Island, he spent his penultimate day painting aboard his small sailboat, the "Widge," capturing the coastal scenery even as autumn storms gathered. William Langson Lathrop passed away on September 21, 1938, at the age of 79.

His legacy extends far beyond his own beautiful canvases. As the founder and nurturing spirit of the New Hope Art Colony, he played an indispensable role in fostering one of America's most important regional art movements. He demonstrated that significant art could flourish outside major metropolitan centers, deeply rooted in the character of a specific place. The community he helped build attracted and supported a remarkable group of artists whose collective work constitutes a vital chapter in American Impressionism. Phillips Mill continues to operate today as an arts center, hosting exhibitions and preserving the creative spirit Lathrop first established there.

Conclusion: An Artist and a Catalyst

William Langson Lathrop was more than just a painter; he was a catalyst. His artistic journey from the introspective moods of Tonalism to the vibrant light of Impressionism reflects broader shifts in American art, yet his work always retained a unique sensitivity and integrity. His depictions of the Delaware Valley landscape are imbued with a quiet authority and a deep, abiding affection for the natural world. Equally important was his role as a mentor, community builder, and the gentle patriarch of the New Hope School. Through his vision and encouragement, he helped launch the careers of numerous artists and established a lasting legacy that continues to enrich American art history. His life and work remain a powerful example of artistic dedication and the profound impact one individual can have on shaping a creative community.