Introduction: A Voice for the Voiceless

Constantin Meunier (1831-1905) stands as a pivotal figure in Belgian art history, a painter and sculptor whose work gave profound expression to the realities of the industrial age. Emerging during a period of immense social and economic transformation, Meunier dedicated much of his mature career to depicting the lives, struggles, and inherent dignity of the working class. Primarily known for his powerful sculptures of miners, puddlers, dockworkers, and other labourers, he moved away from the historical and religious subjects of his early career to embrace a potent form of Social Realism. His art, deeply empathetic yet often monumental in its conception, sought not merely to document but to elevate the modern worker, transforming figures often overlooked into symbols of human endurance, strength, and collective identity. Meunier's unique blend of realistic observation and heroic idealization carved a distinct path in late 19th-century European art, influencing contemporaries and leaving a lasting legacy that continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Brussels

Constantin Meunier was born on April 12, 1831, in Etterbeek, then a working-class suburb of Brussels. His family background, though rooted in traditional labour, faced hardship following the early death of his father, a tax collector. His mother showed considerable resourcefulness, supporting the family by opening a hat shop, managing a fashion magazine, and renting out apartments. This exposure to the realities of economic struggle likely planted early seeds of social awareness in the young Constantin. His elder brother, Jean-Baptiste Meunier, who became a respected engraver and was a student of the notable Italian engraver Luigi Calamatta, provided an early artistic influence and encouragement within the family.

Recognizing his artistic talent, Meunier enrolled at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in September 1845. His initial training focused on sculpture under the guidance of Louis Jehotte, a proponent of a rather conventional academic style. However, Meunier found the prevailing academicism uninspiring. He continued his studies at the private studio of the sculptor Charles-Auguste Fraikin from 1848. Despite this grounding in sculpture, Meunier felt a stronger pull towards painting during these formative years, believing it offered greater expressive possibilities at the time. He began exhibiting paintings as early as 1851, initially focusing on religious scenes and historical portraits that aligned more closely with prevailing tastes.

The Painter: Religious Themes and Early Realism

For nearly three decades, painting remained Meunier's primary medium. His early works often explored religious themes, reflecting both personal piety and the continued market for such subjects. Works like St. Stephen's Martyrdom (lost) and scenes depicting monastic life, such as A Trappist Funeral (c. 1860), showcased his technical skill and his interest in solemn, contemplative moods. These paintings often featured careful compositions, a somewhat somber palette, and an attention to detail characteristic of the Belgian academic tradition influenced by figures like Louis Gallait and Hendrik Leys.

However, Meunier was not isolated from the burgeoning Realist movement sweeping across Europe. He became associated with a circle of progressive Belgian artists who sought to break free from staid academic conventions. A key figure in this group was Charles De Groux, whose depictions of the lives of the poor and working class had a significant impact on Meunier's evolving perspective. De Groux's empathetic portrayal of everyday hardship resonated with Meunier's own developing social conscience. This connection solidified further in 1868 when Meunier, alongside De Groux, Félicien Rops, and others, co-founded the Société Libre des Beaux-Arts. This association explicitly aimed to promote artistic freedom and a more truthful, modern, and often socially engaged approach to art, challenging the dominance of the official Salon system.

The Turning Point: Encountering the "Black Country"

A series of experiences around the late 1870s and early 1880s proved transformative for Meunier's artistic direction. A commission took him to the Val-Saint-Lambert glassworks, and later, travels through the Borinage, Belgium's heavily industrialized coal-mining region often referred to as the "Pays Noir" (Black Country), exposed him directly to the harsh realities of industrial labour. Witnessing the grueling conditions, the physical toll on the workers, and the dramatic landscapes shaped by industry left an indelible mark on him. This period coincided with his growing awareness of the works of French Realists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, whose respective focus on unvarnished reality and the dignity of rural labour provided powerful artistic precedents.

Meunier felt an increasing disconnect between the medium of painting and the raw, physical, and often tragic nature of the subjects he now wished to portray. The suffering, resilience, and sheer physical presence of the miners, glassblowers, and ironworkers seemed to demand a more tangible, three-dimensional form. Around 1880, at the age of nearly fifty, Meunier made a decisive return to sculpture, the medium he had first studied but largely abandoned. He saw in sculpture the potential to convey the weight, solidity, and monumental presence of the modern industrial worker in a way that painting could not fully capture. This shift marked the beginning of the phase for which he would become most renowned.

The Sculptor of Modern Labour

Meunier's return to sculpture was not merely a change of medium; it was a profound shift in artistic purpose. He began creating figures that embodied the spirit of the industrial age. His approach combined meticulous observation, gleaned from sketches made on-site in factories and mines, with a tendency towards heroic generalization. His workers are not simply anonymous labourers; they possess a quiet dignity, a sense of enduring strength even amidst exhaustion and suffering. He avoided overt sentimentality, instead focusing on characteristic poses, the tools of the trade, and the physical impact of demanding labour on the human form.

One of his earliest and most impactful sculptures from this period was The Hammerer (Le Marteleur), first exhibited in bronze at the Paris Salon of 1886. Depicting an ironworker, stripped to the waist, pausing momentarily with his hammer, the sculpture was praised for its powerful realism and its departure from classical or mythological subjects. It captured the physicality and intensity of industrial work, becoming an emblem of the modern labourer. Critics like Octave Mirbeau lauded its truthfulness and expressive force. This success solidified Meunier's reputation as a leading voice in contemporary sculpture.

Iconic Works: Embodying the Industrial Age

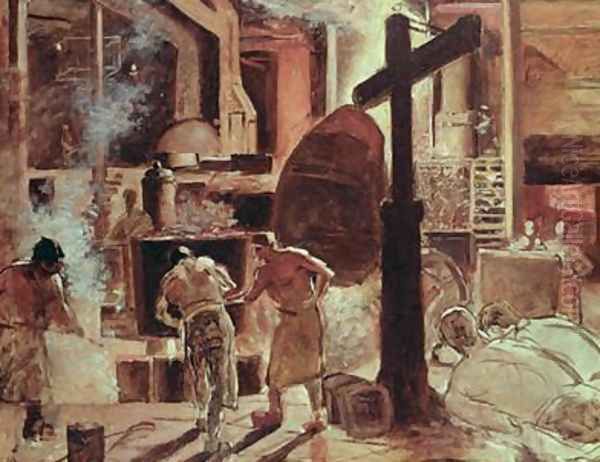

Following the success of The Hammerer, Meunier produced a remarkable series of sculptures focused on the diverse figures of the industrial world. The Puddler (Le Puddleur, c. 1886) depicts a worker stirring molten iron, shielded only by an apron and cap, embodying intense heat and physical exertion. The Docker (Le Débardeur, versions from c. 1885 onwards) captures the raw strength and strain of men loading and unloading ships, their bodies taut with effort. These figures, often cast in bronze, possess a dark, rugged texture that enhances their connection to the materials and environments of industry – coal, iron, smoke, and sweat.

Meunier's exploration of the mining world was particularly profound. He depicted various aspects of the miner's life, from the exhausting work underground to the ever-present danger. Firedamp (Le Grisou, c. 1889) is a harrowing portrayal of a mother discovering the body of her son after a mine explosion, a work directly inspired by the tragic mining disasters common in the Borinage. This sculpture, sometimes compared in its emotional intensity to Michelangelo's Pietà, highlights the human cost of industrial progress. Meunier also sculpted The Old Mine Horse (Le Vieux Cheval de mine, 1891), a poignant image of an animal worn out by years of subterranean toil, symbolizing the exploitation inherent in the system. Other figures, like The Sower (Le Semeur), adapted the traditional image of agricultural labour to the industrial context, suggesting the foundational role of the worker in modern society.

The Monument to Labour: An Epic in Bronze

Meunier's most ambitious project was the Monument to Labour (Monument au Travail). Conceived as early as the 1890s, this large-scale work aimed to be an epic celebration and commemoration of the modern worker in all their forms. Meunier envisioned a complex structure incorporating several individual sculptures and reliefs, representing different facets of labour: Industry (represented by the puddler), The Mine (represented by miners), The Harvest (representing agricultural labour, acknowledging its continued importance), and The Port (represented by the docker). Central reliefs were planned to depict scenes of industrial activity, while freestanding figures like The Sower, The Ancestor (representing the continuity of labour through generations), and The Smith would stand at the corners or front.

Meunier worked tirelessly on the individual components of the monument for years, exhibiting plaster and bronze versions of the figures at various salons and exhibitions across Europe. He saw the project as the culmination of his life's work, a testament to the "tragic and ferocious beauty" he found in the world of labour. Although he secured government support for the project, Meunier died in 1905 before the monument could be fully realized and assembled in its intended form. Thanks to the efforts of his admirers and the Belgian state, a version of the Monument to Labour was eventually erected posthumously in Brussels in 1930, standing today in the Place Jules Van Praet as a powerful, albeit incomplete, realization of his grand vision.

Painting Alongside Sculpture

While sculpture became his dominant mode of expression after 1880, Meunier never entirely abandoned painting. He continued to paint and draw, often exploring themes parallel to his sculptural work or using these media for preparatory studies. His later paintings often depict industrial landscapes, factory interiors, and scenes of working-class life, rendered with a somber palette and a focus on atmosphere and light. Works like Returning from the Pit or scenes inside glass factories complement his sculptures, offering different perspectives on the same world. His drawing skills remained crucial, providing the observational foundation for his three-dimensional work. These later paintings and drawings, though less famous than his sculptures, are integral to understanding his complete artistic vision and his sustained engagement with the social realities of his time.

Travels and Cultural Observations: The Spanish Interlude

In 1882, Meunier undertook a significant journey to Spain, spending several months primarily in Seville. This trip, commissioned to create a copy of a painting by Pedro Campaña, provided him with a rich, contrasting cultural experience far removed from the industrial landscapes of Belgium. His letters from this period reveal a keen observer fascinated by Spanish customs, traditions, and art. He wrote detailed descriptions of Holy Week processions, the drama of bullfights (which he saw as a tragic art form), the vibrant energy of flamenco dance, and the local architecture and street life.

Meunier's observations were not always complimentary. While he admired the religious devotion reflected in the attire of Sevillian women during processions, he expressed rather critical views on their general appearance in his private letters. He also documented his visit to the large Seville Tobacco Factory, noting the working conditions of the female cigar makers (cigarreras) and finding a "picturesque misery" in their colourful headscarves amidst the factory grime. While Spanish themes did not become central to his later work, the journey likely broadened his artistic horizons and provided a different lens through which to view social structures and human expression, reinforcing his interest in authentic, lived experience, whether in sunny Seville or the dark mines of the Borinage.

Artistic Circles: Collaboration and Influence

Throughout his career, Meunier was actively involved in the Belgian art scene. His role in co-founding the Société Libre des Beaux-Arts in 1868 placed him firmly within the progressive camp, alongside artists like Charles De Groux and Félicien Rops, who shared a commitment to realism and artistic independence. Later, his work found a platform with the avant-garde group Les XX (Les Vingt), founded in Brussels in 1883. Although not a formal member, Meunier exhibited works by invitation at their influential annual salons, placing his sculptures alongside paintings by James Ensor, Théo van Rysselberghe, Fernand Khnopff, and international guests like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. This association highlighted the respect Meunier commanded even among artists exploring very different stylistic paths, such as Symbolism and Neo-Impressionism.

Meunier's work resonated strongly with other artists concerned with social themes. His focus on the worker found parallels in the work of French artists like Honoré Daumier (earlier caricatures and paintings of urban life), Jules Dalou (sculptor known for his Triumph of the Republic and figures of labourers), and even Vincent van Gogh, who spent time as a preacher in the Borinage and depicted the miners and peasants with deep empathy. In Germany, Adolph Menzel was also capturing industrial scenes with stark realism. Meunier's relationship with the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin was one of mutual admiration. Rodin recognized the power and originality of Meunier's work, particularly its departure from purely classical aesthetics towards a modern, socially relevant form of sculpture. Meunier, in turn, navigated the complex art world of Paris, exhibiting successfully at the official Salon and independent shows.

Later Life, Recognition, and Legacy

The last two decades of Meunier's life were marked by intense productivity and growing international recognition. His sculptures were exhibited widely across Europe, including major showings in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, and Brussels. Museums began acquiring his work, and he received numerous accolades. Despite suffering from health problems, including heart trouble, he continued to work relentlessly in his studio in Ixelles, Brussels. His dedication was such that he was reportedly working on the final touches of a sculpture, Fertility, just hours before his death. Constantin Meunier died suddenly of heart failure in his studio on April 4, 1905.

His death was mourned as a significant loss to the art world. Meunier's legacy lies in his pioneering role in establishing the industrial worker as a valid and powerful subject for art. He imbued these figures with a heroic dignity previously reserved for mythological heroes or historical figures. His Social Realism avoided propaganda, instead offering a deeply humanistic portrayal of labour in the modern age. He demonstrated that realism could be monumental and that sculpture could engage directly with contemporary social issues. His influence extended to subsequent generations of artists interested in social commentary and the representation of everyday life. The writer Émile Zola, whose novels often explored the harsh realities of working-class life, shared a similar Naturalist spirit with Meunier.

Collections and Enduring Presence

Constantin Meunier's works are held in major museums across Belgium and internationally. The most significant collection resides in the Musée Meunier in Ixelles, Brussels. This museum is housed in the artist's former home and studio, which he had built in the later years of his life. Donated to the Belgian state after his death, it opened as a museum in 1939. It preserves the atmosphere of his working environment and contains over 700 works, including numerous sculptures in plaster and bronze, paintings, drawings, and sketches, offering an unparalleled overview of his career, particularly his focus on social and industrial themes from 1875 onwards.

Other major Belgian institutions with important holdings include the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, which houses key bronze casts including figures from the Monument to Labour like The Docker, and the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA). His works can also be found in collections in France (Musée d'Orsay, Paris), Germany, the Netherlands, and the United States (including a version of The Hammerman at Columbia University). Temporary exhibitions continue to explore his work, such as retrospectives held in Antwerp (2014) and exhibitions examining his relationship with specific regions like Liège or his time in Spain (Seville, 2008). Through these collections and ongoing scholarly interest, Constantin Meunier's powerful vision of the modern worker remains accessible and relevant.

Conclusion: The Dignity of Labour

Constantin Meunier carved a unique and enduring niche in the landscape of 19th-century art. By turning his focus from conventional subjects to the heart of the industrial world, he gave artistic form to a previously marginalized segment of society. His miners, puddlers, and dockworkers are more than just representations of labour; they are testaments to human resilience, strength, and the profound, often tragic, beauty Meunier perceived in their toil. Through his mastery of both painting and, most significantly, sculpture, he created a body of work that is both historically specific to the Belgian industrial revolution and universally resonant in its exploration of human dignity in the face of hardship. His Monument to Labour, even in its posthumously assembled state, remains a landmark achievement, embodying his lifelong commitment to honouring the foundational role of the worker in shaping the modern world. Meunier remains a crucial figure for understanding the intersection of art, industry, and social consciousness at the turn of the twentieth century.