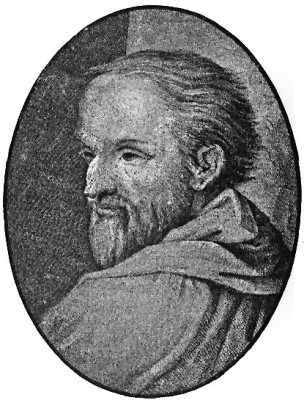

Antonio Allegri (c. 1489 – March 5, 1534), universally known as Correggio after his birthplace in Emilia-Romagna, Italy, stands as one of the most distinctive and influential painters of the Italian High Renaissance. Active primarily in Parma, he developed a style characterized by its sensuous softness, dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), dynamic compositions, and profound emotional depth. Though geographically somewhat removed from the main artistic centers of Florence, Rome, and Venice, Correggio absorbed and synthesized the innovations of his contemporaries, forging a unique path that anticipated key elements of the later Baroque and Rococo periods. His legacy lies not only in his breathtaking frescoes and altarpieces but also in his pioneering approach to illusionism and the depiction of tender, often ecstatic, human feeling.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the small town of Correggio, near Reggio Emilia, around 1489, Antonio Allegri came from a moderately prosperous family; his father, Pellegrino Allegri, was a merchant, and his mother, Bernardina Piazzoli degli Ormani, had noble connections. Details about his earliest artistic training remain somewhat obscure and debated among scholars. Giorgio Vasari, the famed biographer of Renaissance artists, provides limited and sometimes contradictory information. Some early accounts suggest training in Modena under Francesco Bianchi Ferrari, though Ferrari died when Correggio was still young.

More significant and widely accepted is the influence of the artistic environment in Mantua, a major cultural center ruled by the Gonzaga family. It is highly probable that the young Correggio studied the works of Andrea Mantegna, the dominant artistic figure in Mantua until his death in 1506. Mantegna's mastery of perspective, classical forms, and dramatic foreshortening undoubtedly left a mark on Correggio, particularly visible in his later experiments with illusionistic ceiling painting.

Another crucial figure in Mantua during Correggio's formative years was Lorenzo Costa the Elder, who became court painter after Mantegna's death. Costa, originally from Ferrara but also influenced by the Bolognese school (particularly Francesco Francia), likely played a significant role in shaping Correggio's early style. Elements of Costa's softer modeling and perhaps his "pearly Ferrarese coloring" can be discerned in Correggio's initial works. While direct apprenticeship is unproven for either Mantegna or Costa, their impact, absorbed through study and observation in Mantua, seems undeniable. This period likely exposed Correggio to the broader artistic currents flowing through Northern Italy.

The Move to Parma and Early Commissions

By the 1510s, Correggio began establishing his independent career. While he maintained ties to his hometown, the city of Parma became the primary center of his artistic activity and the site of his greatest achievements. His arrival in Parma marked the beginning of a period where he would develop his mature style, blending the influences of his Northern Italian predecessors with the groundbreaking developments emanating from Central Italy.

His early works from this period, often smaller devotional paintings or altarpieces for local churches, show a gradual evolution. Works like the Madonna and Child with St. Francis (c. 1514-1515, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), painted for the church of San Francesco in Correggio, demonstrate his growing confidence. While still showing links to Costa and Mantegna, the painting reveals a burgeoning interest in softer transitions of light and shade and a more tender interaction between the figures, hinting at the influence of Leonardo da Vinci.

Other significant works from this early Parma phase include several variations on the theme of the Madonna and Child, such as the Zingarella (Madonna and Child with a Rabbit) (c. 1516-1517, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples) and the Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist (c. 1516, Art Institute of Chicago). These paintings showcase his developing ability to infuse religious scenes with warmth, intimacy, and a gentle naturalism, moving away from the sterner classicism of Mantegna.

The Parma Period: Major Fresco Commissions

Correggio's reputation grew, leading to major commissions for fresco decorations in Parma, which represent the pinnacle of his career and cemented his place in art history. These ambitious projects allowed him to fully explore his innovative ideas about illusionism, composition, and emotional expression on a grand scale.

The Camera di San Paolo

Around 1519, Correggio received a prestigious commission from Abbess Giovanna Piacenza to decorate her private dining room, the Camera di San Paolo, in the Benedictine convent of San Paolo in Parma. This work marks a significant departure, showcasing Correggio's engagement with classical mythology and humanist themes, possibly influenced by Mantegna's Camera degli Sposi in Mantua but executed with a lighter, more playful touch.

The ceiling is ingeniously designed as a leafy pergola, pierced by oval openings (oculi) through which charming putti peer down against a simulated sky. Below the pergola, lunettes feature monochrome representations of mythological figures related to the theme of the huntress Diana, a subtle allusion to the patroness's virtue and independence. The overall effect is one of delightful illusion and sophisticated charm, demonstrating Correggio's mastery of perspective and his ability to create a lighthearted, almost Arcadian atmosphere within a private space.

The Dome of San Giovanni Evangelista

Following the success of the Camera di San Paolo, Correggio embarked on an even more ambitious project: the decoration of the dome, apse, and choir vault of the church of San Giovanni Evangelista in Parma (1520-1524). For the main dome, he painted the Vision of St. John the Evangelist on Patmos. This work represents a revolutionary step in illusionistic ceiling painting.

Correggio depicted Christ ascending into heaven, surrounded by the Apostles seated on clouds around the base of the dome. The viewer, standing below, experiences the scene as if the architecture has dissolved, opening directly into the heavens. Christ is dramatically foreshortened (sotto in sù), a technique derived from Mantegna but employed here with unprecedented dynamism and fluidity. The Apostles gaze upwards in awe, their powerful, Michelangelesque forms swirling within the celestial space. The intense light emanating from Christ bathes the scene in a golden glow, unifying the composition and enhancing the mystical, visionary quality of the event. This work established a new benchmark for dome decoration, profoundly influencing later Baroque artists.

The Dome of Parma Cathedral

Correggio's final and perhaps most famous fresco cycle was the decoration of the dome of Parma Cathedral, depicting the Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1526-1530). This monumental work pushed the boundaries of illusionism even further, creating an ecstatic vortex of figures spiraling upwards towards divine light.

At the base of the dome, the Apostles stand on a painted balustrade, witnessing the Virgin Mary being carried aloft by a swirling multitude of angels and heavenly beings. The figures diminish in size as they ascend, creating a powerful sense of infinite space. Correggio abandoned clear architectural divisions, allowing the figures to tumble and soar in a seemingly weightless, joyous celebration. The sheer number of figures, their dynamic movement, and the overwhelming effect of light and color create an intensely emotional and immersive experience for the viewer below. The Assumption is a masterpiece of High Renaissance art that directly anticipates the dramatic intensity and theatricality of the Baroque era. Its daring foreshortening and swirling composition were groundbreaking, though reportedly met with some initial criticism for their radical departure from tradition.

Mastery of Technique and Style

Correggio's art is defined by a unique synthesis of techniques and stylistic concerns that set him apart from his contemporaries. His handling of light, composition, and emotion created a signature style that was both innovative and deeply appealing.

Light and Shadow (Chiaroscuro and Sfumato)

Correggio was a supreme master of light and shadow. He clearly absorbed the lessons of Leonardo da Vinci's sfumato – the soft, hazy transitions between tones – but adapted it to create effects that were warmer, more sensuous, and often more dramatic. His chiaroscuro is not merely about modeling form but about creating atmosphere, enhancing emotional intensity, and directing the viewer's eye.

In works like the Adoration of the Shepherds (known as La Notte or The Night, c. 1529-1530, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), the divine light emanating from the Christ Child becomes the primary light source, illuminating the faces of the Virgin and the shepherds with a tender radiance while plunging the surrounding scene into deep shadow. This dramatic use of light heightens the miraculous nature of the event and imbues it with profound intimacy and awe. His flesh tones often have a soft, luminous quality, giving his figures a palpable, almost breathing presence.

Dynamic Composition and Illusionism

Correggio broke free from the stable, often symmetrical compositions favored by many earlier Renaissance artists. He embraced dynamic diagonals, swirling movements, and complex groupings of figures that convey energy and emotion. His mastery of foreshortening (sotto in sù), particularly in his dome frescoes, was revolutionary.

By painting figures as seen from directly below, he created the illusion that they are truly occupying the space above the viewer, dissolving the barrier between the painted world and the real world. This technique, pioneered by Mantegna, was taken to new heights by Correggio, who used it not just as a technical feat but as a means of enhancing the spiritual or emotional impact of the scene, drawing the viewer into the depicted event. His compositions often feel fluid and unstable, capturing moments of transition, ecstasy, or tender interaction.

Emotional Depth and Sensuousness

Perhaps Correggio's most defining characteristic is his ability to convey subtle and intense emotions. His figures, whether divine or mythological, are imbued with a remarkable psychological presence. He excelled at depicting tenderness, grace, joy, and spiritual ecstasy. The interactions between his figures, particularly the intimate bond between the Madonna and Child, are rendered with unparalleled sensitivity.

There is also a distinct sensuousness in Correggio's art, evident in the soft modeling of flesh, the gentle expressions, and the graceful poses of his figures. This quality is particularly apparent in his mythological paintings, but it also infuses his religious works with a human warmth and accessibility that was highly original. He managed to combine spiritual intensity with an appreciation for physical beauty in a way that was uniquely his own.

Influences and Artistic Dialogue

Correggio's unique style emerged from a rich dialogue with the art of his predecessors and contemporaries. While geographically somewhat isolated in Parma, he was clearly aware of the major artistic developments of his time.

Leonardo da Vinci's Legacy

The influence of Leonardo da Vinci is palpable in Correggio's work, particularly in his use of sfumato, his subtle modeling of form, and his interest in capturing fleeting expressions and psychological states. Correggio likely encountered Leonardo's work during visits to Milan or through drawings and copies. However, Correggio adapted Leonardo's techniques to his own sensibility, often achieving a warmer, softer, and more overtly emotional effect. The gentle smiles and tender interactions in Correggio's Madonnas echo Leonardo, but with a distinct sweetness.

Echoes of Raphael and Michelangelo

Correggio also seems to have absorbed lessons from the two giants of the High Renaissance in Rome, Raphael and Michelangelo. From Raphael, he may have taken inspiration for the grace, harmony, and idealized beauty of his figures, particularly his Madonnas and angels. The sweetness and gentle movement in some of Correggio's compositions recall Raphael's Umbrian and Florentine periods.

The impact of Michelangelo is most evident in the powerful, muscular figures and dynamic poses found in Correggio's frescoes, such as the Apostles in the dome of San Giovanni Evangelista. A trip to Rome around 1518-1519, though not definitively documented, is often postulated by scholars, as it would explain his apparent firsthand knowledge of the Sistine Chapel ceiling and Raphael's Stanze frescoes in the Vatican. Correggio integrated these influences without sacrificing his own lyrical and sensuous style.

Mantegna, Costa, and the Northern Italian Context

As discussed earlier, Andrea Mantegna and Lorenzo Costa were foundational influences. Mantegna provided a model for perspective, foreshortening, and classical rigor, which Correggio transformed with greater softness and dynamism. Costa, along with other artists of the Ferrarese and Bolognese schools like Francesco Francia, likely contributed to Correggio's understanding of color and composition in the North Italian tradition.

Furthermore, Correggio's sensitivity to color and light might also reflect an awareness of the developments in Venetian painting, particularly the work of artists like Giorgione and the young Titian, known for their atmospheric effects and rich color palettes. While Correggio's style remained distinct from the Venetians, his emphasis on painterly effects and emotional atmosphere aligns with broader trends in Northern Italian art of the period. He may also have been aware of Ferrarese contemporaries like Dosso Dossi, known for their imaginative and sometimes eccentric subjects.

Notable Easel Paintings and Mythologies

Beyond his monumental frescoes, Correggio produced a significant body of work on panel and canvas, including altarpieces and mythological scenes, which further showcase his unique talents.

His altarpieces are among the most beloved works of the High Renaissance. The Madonna of St. Sebastian (c. 1524, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden) and the Madonna of St. Jerome (better known as Il Giorno or The Day, c. 1527-1528, Galleria Nazionale, Parma) exemplify his mature style. Il Giorno is celebrated for its brilliant light, harmonious composition, and the tender, playful interaction between the Christ Child, St. John, Mary Magdalene, and St. Jerome. Its counterpart, La Notte (Adoration of the Shepherds), is famed for its revolutionary handling of nocturnal light.

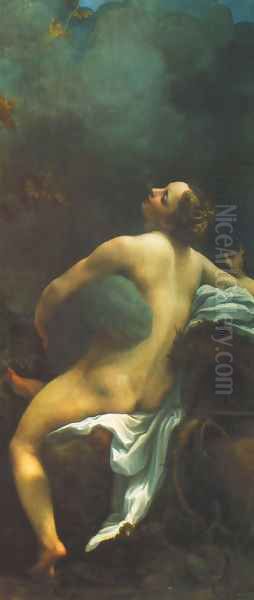

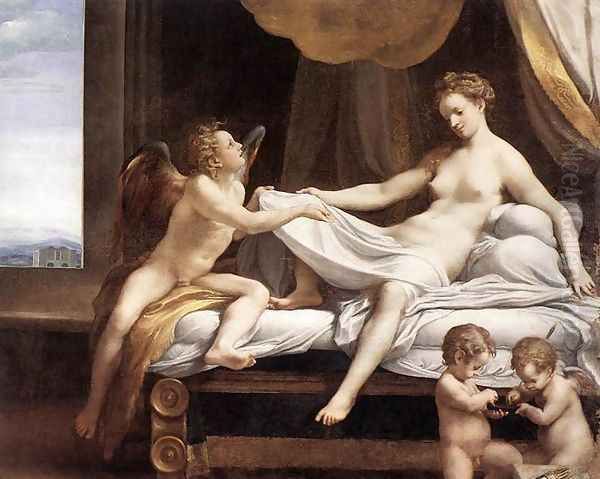

Correggio also excelled in mythological subjects, often imbued with a soft eroticism and lyrical beauty. A notable series, known as the Loves of Jupiter, was commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, likely intended as a gift for Emperor Charles V. These paintings depict Jupiter's mythological affairs with mortals: Jupiter and Io (c. 1531-1532, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle (c. 1531-1532, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), Leda and the Swan (c. 1531-1532, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), and Danaë (c. 1531, Galleria Borghese, Rome). These works are masterpieces of sensuousness, showcasing Correggio's ability to render soft flesh, atmospheric effects (like the cloud enveloping Io), and intense emotion.

Other important easel paintings include the Venus, Satyr and Cupid (also known as The Sleep of Antiope, c. 1528, Louvre, Paris) and The Education of Cupid (c. 1528, National Gallery, London), both demonstrating his graceful handling of the nude figure and his charming depiction of mythological themes. His numerous depictions of the Madonna and Child and the Holy Family, often characterized by intimate scale and tender emotion, were highly sought after.

Working Methods and Anecdotes

Correggio's working process involved careful preparation. Surviving drawings, often executed in red chalk, reveal his method of studying figures and compositions. These drawings possess a characteristic softness and fluidity, capturing the graceful movement that defines his finished paintings. For his complex dome frescoes, it is believed he may have used small wax or clay models to work out the challenging foreshortening and spatial arrangements, ensuring the illusionistic effect would be convincing from below.

Anecdotes surrounding Correggio often emphasize his gentle nature and perhaps a certain provincial modesty. Vasari tells a possibly apocryphal story of Correggio's supposed reaction upon seeing a work by Raphael: "Anch'io sono pittore!" ("I too am a painter!"), suggesting a quiet confidence in his own abilities despite his distance from the Roman center. Another legend, likely untrue, describes him dying prematurely from exhaustion after carrying a large payment in heavy copper coins back to his hometown. While such stories add color, his true personality remains elusive, overshadowed by the sheer beauty and innovation of his art. An earlier anecdote mentioned him being accidentally burned by a torch in his youth, and another tells of him taking a statue of a saint home, after which his fortunes improved – these likely belong more to legend than fact but reflect the fascination he inspired.

Legacy and Influence

Despite the brilliance of his Parma frescoes and the appeal of his easel paintings, Correggio did not enjoy the same level of widespread fame during his lifetime as masters like Raphael or Titian. His location in Parma, away from the major artistic thoroughfares, and his relatively early death at around age 45 may have contributed to this. However, his influence, though perhaps delayed, was profound and long-lasting.

His true rediscovery began in the late 16th and 17th centuries with the rise of the Baroque. The Carracci family – Ludovico, Agostino, and Annibale Carracci – founders of the influential Bolognese academy, deeply admired Correggio's work in Parma. They recognized the emotional power, the masterful handling of light, and the innovative illusionism of his frescoes. Annibale Carracci's own fresco cycles, such as those in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, show a clear debt to Correggio's dynamism and sensuousness.

Correggio's dome paintings became direct models for Baroque ceiling decoration. Artists like Giovanni Lanfranco, who worked in Parma before moving to Rome, explicitly drew upon Correggio's Assumption for his own spectacular dome fresco in Sant'Andrea della Valle in Rome, popularizing the swirling, illusionistic style. Correggio's approach to light and emotion also resonated with Baroque masters across Italy and beyond.

In the 18th century, Correggio experienced another wave of appreciation during the Rococo period. Artists and connoisseurs were drawn to the grace, charm, and sensuous softness of his style. French painters like François Boucher admired his mythological scenes and his tender depictions of women and children. Correggio's emphasis on delicate sentiment and painterly beauty found fertile ground in the aesthetic sensibilities of the Rococo era. He was hailed as a master of grace and feeling, a precursor to the lighter, more intimate art of the 18th century.

Conclusion

Antonio Allegri da Correggio remains a unique and captivating figure in the history of Italian art. Working largely in Parma, he synthesized the achievements of the High Renaissance – the sfumato of Leonardo, the grace of Raphael, the power of Michelangelo, and the perspective of Mantegna – into a style entirely his own. His mastery of light created unparalleled effects of softness, warmth, and drama. His pioneering use of illusionistic perspective transformed ceiling painting, paving the way for the theatricality of the Baroque. Above all, his ability to convey tender emotion, spiritual ecstasy, and sensuous beauty imbued his art with an enduring human appeal. Though perhaps less famous than some of his contemporaries during his lifetime, Correggio's innovative spirit and profound sensitivity left an indelible mark on European painting, influencing generations of artists and continuing to enchant viewers centuries later. He stands as a testament to the rich diversity of the Italian Renaissance and a crucial bridge to the artistic developments that followed.