Gaudenzio Ferrari stands as a pivotal figure in the artistic landscape of the Italian Renaissance, particularly celebrated for his profound contributions to the Piedmontese and Lombard schools of painting and sculpture. Active during a period of immense artistic innovation, Ferrari carved a unique niche for himself, blending the emotional intensity and detailed realism often associated with Northern European art with the grace and humanism of the Italian masters. His extensive body of work, predominantly religious in theme, adorns numerous churches and sacred sites, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural heritage of Northern Italy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Valduggia, a small town in the Valsesia region of Piedmont, around 1475-1480, Gaudenzio Ferrari's early life was steeped in the rugged, devout atmosphere of the Alpine foothills. This environment likely shaped his artistic sensibilities, instilling in him a penchant for vivid storytelling and expressive force. While precise details of his earliest training remain somewhat obscure, it is widely accepted that he journeyed to Milan to hone his craft.

In Milan, a vibrant artistic hub, Ferrari would have been exposed to a confluence of influential styles. He is believed to have studied under artists such as Giovanni Martino Spanzotti, a leading figure in Piedmontese art, and later, possibly with Stefano Scotto or even Bernardino Luini, a prominent follower of Leonardo da Vinci. The towering presence of Leonardo himself in Milan during Ferrari's formative years undoubtedly left a significant impression, evident in the subtle sfumato and psychological depth found in some of Ferrari's figures.

Further enriching his artistic vocabulary, Ferrari is thought to have encountered the works of Bramante, whose architectural principles and understanding of perspective were transforming Milanese art. He also absorbed influences from Vincenzo Foppa, considered one of the founders of the Lombard school, known for his austere realism and expressive power. This period of learning was crucial, allowing Ferrari to synthesize diverse artistic currents into a style that was distinctly his own. Some scholars also suggest early contact with the works of Perugino, perhaps through Bramantino (Bartolomeo Suardi), which might account for some of the Umbrian sweetness in his early figures.

Artistic Style and Characteristics

Gaudenzio Ferrari's artistic style is characterized by its dynamic energy, emotional intensity, and a remarkable fusion of naturalism with a heightened sense of drama. He was a master of narrative, capable of conveying complex biblical stories with clarity and profound feeling. His figures are often robust and animated, their faces etched with a wide range of human emotions, from ecstatic joy to profound sorrow.

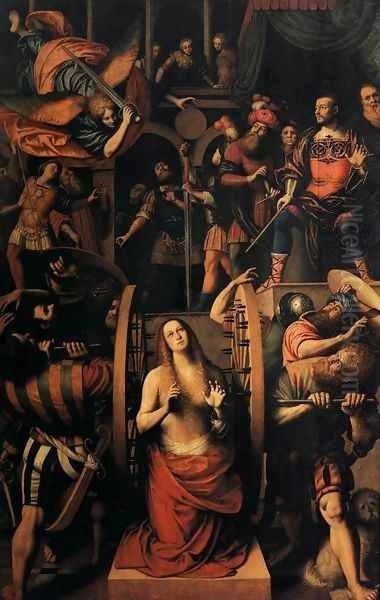

A hallmark of Ferrari's work is its theatricality. He frequently employed crowded compositions, filled with figures in dynamic poses, creating a sense of movement and immediacy. This dramatic quality was particularly effective in his large-scale fresco cycles, where he transformed entire walls and chapels into immersive spiritual experiences. He was not afraid to use bold, sometimes even jarring, colors to heighten the emotional impact of his scenes.

Ferrari also demonstrated a keen interest in realism, meticulously rendering details of costume, texture, and landscape. This attention to the tangible world, possibly influenced by Northern European art, grounded his often-supernatural subjects in a relatable reality. His skill extended beyond painting to sculpture, particularly in terracotta, which he often integrated with his frescoes to create three-dimensional, life-like tableaux, most notably at the Sacro Monte di Varallo. This multimedia approach was innovative and greatly enhanced the devotional experience for the viewer. The influence of artists like Andrea Mantegna can be discerned in the sculptural quality of his figures and his command of perspective.

The Sacro Monte di Varallo: A Monumental Achievement

Perhaps Gaudenzio Ferrari's most significant and enduring legacy is his extensive work at the Sacro Monte (Sacred Mountain) di Varallo. This unique devotional complex, conceived as a "New Jerusalem" in the Alps, comprises a series of chapels depicting scenes from the life of Christ. Ferrari was instrumental in bringing this vision to life, working there intermittently from the early 16th century until around 1528.

His contributions to the Sacro Monte are multifaceted, encompassing both frescoes and life-sized, polychrome terracotta sculptures. In chapels such as the Crucifixion, the Adoration of the Magi, and the Journey to Calvary, Ferrari created immersive environments where painted backgrounds seamlessly merge with sculpted figures. The effect is startlingly realistic and emotionally charged, designed to draw the pilgrim directly into the sacred narrative.

The Crucifixion chapel (Chapel XXXVIII), for instance, is a tour de force of dramatic composition and psychological insight. The wall fresco depicts a vast crowd beneath the three crosses, with a multitude of figures expressing a spectrum of reactions to Christ's suffering. In front of this, sculpted figures of Christ, the thieves, Mary, and John create a powerful three-dimensional focal point. This innovative combination of media was revolutionary for its time and set a precedent for similar sacred mountain complexes throughout Northern Italy and beyond.

Other notable works at Varallo include the frescoes in the Chapel of the Adoration of the Magi (Chapel V), where Ferrari displays his skill in depicting opulent textures and a diverse cast of characters, and the poignant scenes in the Chapel of the Pietà (Chapel XL). His ability to orchestrate these complex ensembles, integrating painting, sculpture, and architecture, underscores his remarkable versatility and visionary approach.

Major Fresco Cycles and Altarpieces

Beyond Varallo, Gaudenzio Ferrari undertook numerous important commissions for churches and religious institutions across Piedmont and Lombardy. His fresco cycles are particularly noteworthy for their scale and narrative power.

In the early 1510s, he painted significant frescoes in the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Varallo, including scenes from the life of the Virgin and a powerful Last Supper. These works demonstrate his growing mastery of complex compositions and emotional expression. His Madonna and Angels in this church is a celebrated piece, showcasing his ability to imbue sacred figures with warmth and humanity.

Around 1513, Ferrari created the Polyptych of Saint Anne for the church of Sant'Anna in Vercelli, a work that reveals his engagement with the High Renaissance ideals of harmony and grace, while still retaining his characteristic expressive intensity.

A significant commission was the decoration of the cupola of the Santuario della Beata Vergine dei Miracoli in Saronno (c. 1534-1536). Here, Ferrari painted a celestial concert of angels, a swirling, dynamic composition that anticipates Baroque dome painting. This work is often compared to Correggio's dome frescoes in Parma for its illusionistic power and sense of divine energy, though Ferrari's style remains more robust and less idealized than Correggio's.

In Milan, where he spent his later years, Ferrari executed important works, including frescoes in Santa Maria della Passione. His Last Supper in this church, though perhaps overshadowed by Leonardo's iconic version, is a significant work in its own right, notable for its dramatic lighting and the varied emotional responses of the apostles. He also painted altarpieces for various Milanese churches, further solidifying his reputation in the Lombard capital.

Among his panel paintings, works like St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata (c. 1515-1517) and various depictions of the Madonna and Child highlight his skill in rendering tender emotions and rich textures. The St. Christopher is another example of his powerful figure style.

Influences, Contemporaries, and School

Gaudenzio Ferrari's art was a product of rich cross-currents. While Leonardo da Vinci's influence is undeniable, particularly in the subtlety of expression and atmospheric effects, Ferrari's work often possesses a more overt emotionalism and a ruggedness that distinguishes it from Leonardo's refined classicism. The influence of Raphael can be seen in the compositional harmony of some of his works, but Ferrari rarely adopted Raphael's idealized beauty, preferring a more earthy, vigorous portrayal of humanity.

He was a contemporary of other great Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo and Titian, though his sphere of activity was primarily regional. Within Lombardy, he interacted with and influenced a generation of artists. His relationship with Bramantino (Bartolomeo Suardi) is complex; while both were key Lombard painters, Ferrari’s style was generally more expansive and dramatic. He certainly knew the work of other Milanese artists like Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio and Andrea Solario.

Ferrari also ran an active workshop and had several pupils and followers who helped disseminate his style. The most notable of these was Bernardino Lanino, who inherited Ferrari's workshop and continued his artistic legacy, albeit often with a softer, more graceful touch. Other artists associated with his circle include Antonio Solari, Giovanni Battista da Cerva, and Fermo Stella. Sperindio Cagnoli is also documented as having collaborated with Ferrari, for instance, on a version of the Last Supper.

His engagement with Northern European art, possibly through prints or itinerant artists, is evident in his attention to detail, expressive intensity, and sometimes even in the angularity of his figures, which can recall German masters like Albrecht Dürer or Matthias Grünewald, though direct links are speculative. What is clear is his departure from a purely classical Italianate idiom towards a more expressive, populist style well-suited to the devotional needs of his patrons.

Later Career and Milanese Period

In the later part of his career, from around 1539, Gaudenzio Ferrari established himself more permanently in Milan. This move brought him into closer contact with the artistic trends of one of Italy's major cultural centers. During this period, he continued to receive significant commissions, including the aforementioned frescoes in Santa Maria della Passione and various altarpieces.

His style in these later years maintained its characteristic vigor, but perhaps showed an increased sophistication and a deeper psychological penetration in his figures. The Milanese artistic environment, with its ongoing dialogue between Leonardo's legacy and newer artistic currents, likely provided fresh stimuli for his work.

The death of his wife and son during this period is thought by some art historians to have cast a shadow over his later works, possibly infusing them with a more somber or introspective quality. However, his artistic output remained prolific and highly sought after. He passed away in Milan in 1546, leaving behind a substantial body of work that had significantly shaped the artistic identity of Piedmont and Lombardy. While some sources occasionally mention a death year of 1550, 1546 is the most widely accepted date.

Personal Life and Its Echoes in Art

Details about Gaudenzio Ferrari's personal life are relatively scarce, as is common for many artists of his era. It is known that he was born in Valduggia to Franchino Ferrari. He married at least twice. His first wife was Maria Mattia, and after her death, he married Margherita Fagnani. He had at least two children, a son named Gerolamo and a daughter named Margherita.

The loss of family members, particularly his later wife and son, is believed by some scholars to have influenced the emotional tenor of his subsequent art. While direct correlations are difficult to prove, the profound empathy and human understanding evident in his religious scenes suggest an artist deeply attuned to the spectrum of human experience, including grief and suffering.

His dedication to his craft was unwavering, and his life seems to have been largely centered around his artistic production and the fulfillment of numerous commissions. His strong ties to his native Valsesia region remained throughout his life, even after he established himself in Milan.

Unresolved Questions and Attributions

Like many Renaissance artists, Gaudenzio Ferrari's oeuvre presents certain unresolved questions and attributional challenges for art historians. The scarcity of detailed documentation for some of his early works makes a complete reconstruction of his artistic development difficult.

Attribution issues occasionally arise. For example, some works once attributed to Ferrari have subsequently been reassigned to his pupils or workshop, such as a Madonna and Child now often given to Bernardino Lanino. Conversely, works by lesser-known artists might sometimes be optimistically attributed to the master. The precise extent of workshop participation in his larger commissions is also a subject of ongoing study.

There are mentions of lost works, including a "musical fresco," the absence of which leaves a gap in our understanding of his full range. Furthermore, the specific iconographic programs and theological underpinnings of some of his complex fresco cycles, particularly at the Sacro Monte di Varallo, continue to be explored and debated by scholars. For instance, the exact narrative intent behind a series of four paintings thought to depict scenes from the lives of Saint Bovus and Saint Eligius remains somewhat enigmatic.

Restoration efforts on his works sometimes reveal new information. For example, technical analysis, such as 3D scanning during the restoration of a piece like the Announcing Angel, can uncover underdrawings or changes in composition, offering fresh insights into his creative process but also sometimes raising new questions. These ongoing investigations ensure that Ferrari's art remains a vital field of study.

Legacy and Historical Reassessment

In his own time, Gaudenzio Ferrari was highly esteemed, particularly in Piedmont and Lombardy. His contemporaries recognized his exceptional talent, and he was often compared favorably with the greatest masters of the age. Giorgio Vasari, in his "Lives of the Artists," mentions Ferrari, though perhaps not with the extensive praise afforded to central Italian masters, reflecting Vasari's Tuscan bias. However, Lombard writers like Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo lauded him as one of the "seven governors" of art, alongside giants like Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Despite this contemporary acclaim, Ferrari's fame somewhat diminished in subsequent centuries, partly due to his regional focus and the shifting tastes of later periods. His work, deeply rooted in the specific devotional culture of Northern Italy, did not always align with the more classical or academic aesthetics that came to dominate art criticism.

However, the 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a significant reassessment of Ferrari's contributions. Art historians began to recognize the unique power and originality of his art, particularly his innovative work at the Sacro Monte di Varallo and his role as a leading figure in the Lombard school. Exhibitions dedicated to his work, such as those held in Varallo, Vercelli, and Novara, have helped to bring his achievements to a wider audience.

Today, Gaudenzio Ferrari is acknowledged as a major artist of the High Renaissance in Northern Italy. His ability to synthesize diverse influences, his mastery of multiple media, and the profound emotional impact of his work secure his place as a distinctive and important voice in the chorus of Renaissance art. His influence on subsequent generations of Lombard and Piedmontese artists, most notably through his student Bernardino Lanino, was considerable, shaping the trajectory of religious art in the region for decades to come.

Conclusion

Gaudenzio Ferrari was an artist of remarkable energy, profound spiritual depth, and innovative vision. From the dramatic, multimedia ensembles of the Sacro Monte di Varallo to his powerful fresco cycles and expressive altarpieces, he created a body of work that continues to resonate with viewers. His unique blend of Northern European realism and Italian Renaissance humanism, infused with a passionate emotional intensity, set him apart from his contemporaries. While perhaps not as universally known as some of the Florentine or Roman masters, Gaudenzio Ferrari's artistic achievements represent a crucial chapter in the story of Italian art, a testament to the rich and diverse cultural landscape of the Renaissance. His legacy endures in the sacred spaces he adorned and in the ongoing appreciation of his powerful and deeply human art.