William Maw Egley (1826-1916) stands as a fascinating, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of British Victorian art. Born in London, the very heart of an empire at its zenith, Egley's life and career spanned a period of immense social, industrial, and artistic change. As an artist, he navigated the prevailing currents of his time, from the lingering influence of earlier genre painters to the revolutionary fervor of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His work, characterized by meticulous detail and a keen observational eye, offers valuable insights into the mores, fashions, and everyday realities of Victorian England. While he may not have achieved the towering fame of some of his contemporaries, Egley's contributions, particularly his depictions of contemporary life and his early forays into literary illustration, secure him a distinct place in art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

William Maw Egley was born in London in 1826, into a family already connected to the art world. His father, William Egley (1798-1870), was a respected miniature painter. This familial connection undoubtedly provided the young Egley with an early immersion in artistic practice and discussion. It was from his father that he received his initial training, learning the foundational skills of drawing and painting. This apprenticeship within the family studio would have emphasized precision and careful observation, qualities that would become hallmarks of his later style.

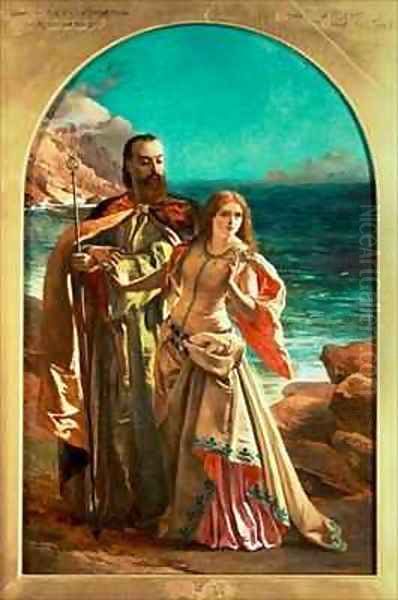

In his formative years as an independent artist, Egley was drawn to literary themes, a popular subject choice in an era that highly valued narrative and moral instruction in art. His early works often featured illustrations of characters and scenes from esteemed authors, most notably William Shakespeare. An example from this period is his depiction of Prospero and Miranda from "The Tempest." These initial efforts showed an affinity with the stylistic tendencies of "The Clique," a group of young artists formed in the late 1830s that included Richard Dadd, Augustus Egg, Alfred Elmore, William Powell Frith, Henry Nelson O'Neil, and John Phillip. Though Egley wasn't a formal member, the group's preference for historical and literary subjects, rendered with a degree of anecdotal detail, resonated in his early output.

The Influence of "The Clique" and William Powell Frith

The artistic environment of London in the 1840s and 1850s was vibrant and competitive. "The Clique," though short-lived as a formal group, represented a reaction against the perceived staidness of the Royal Academy's high art ideals, favoring instead subjects that were more accessible and engaging to the burgeoning middle-class audience. Their work often featured historical genre, literary scenes, and contemporary social commentary, rendered with a clarity and narrative drive that proved popular.

Among the members of "The Clique," William Powell Frith (1819-1909) was to become particularly significant for Egley. Frith rose to immense fame with his panoramic depictions of modern life, such as Ramsgate Sands (Life at the Seaside) (1854), The Derby Day (1858), and The Railway Station (1862). These large-scale canvases, teeming with incident and character, captured the public imagination. Egley developed a close working relationship with Frith, a connection that proved mutually beneficial. It is documented that Egley often assisted Frith by painting backgrounds for his elaborate compositions. This collaboration would have provided Egley with invaluable experience in constructing complex scenes and managing multiple figures, skills that he would later apply to his own ambitious works.

Frith's influence on Egley extended beyond mere technical assistance. The success of Frith's modern-life subjects likely encouraged Egley to explore similar themes. While Egley's canvases rarely reached the epic scale of Frith's major works, he adopted a similar focus on observing and recording the nuances of contemporary society, often with a gentle, humorous touch. His paintings began to feature themes of family life, childhood, and the everyday interactions of urban and rural people, moving beyond purely literary inspiration to engage more directly with the world around him.

Omnibus Life in London: A Victorian Masterpiece

Perhaps William Maw Egley's most famous and enduring work is Omnibus Life in London, painted in 1859. This painting is a quintessential example of Victorian genre painting, capturing a vivid cross-section of society within the cramped confines of a horse-drawn omnibus. The Tate Britain, which holds the painting, notes its detailed depiction of the various passengers, each absorbed in their own world yet forced into close proximity.

The composition is masterful in its use of the limited space. Passengers are arranged to create a sense of both intimacy and social distance. We see a mother with her children, a city clerk, a fashionable young woman, an elderly gentleman, and others, each character delineated with specific attention to costume, posture, and facial expression. The details are telling: the newspapers being read, the baskets and parcels, the weary expressions of some and the alert curiosity of others. Egley's meticulous rendering of fabrics, from the crisp crinoline of a lady's dress to the worn broadcloth of a working man's coat, adds to the painting's realism.

Omnibus Life in London is more than just a charming scene; it is a social document. It reflects the increasing urbanization of London and the rise of public transport, which brought together people from different social strata in new ways. The painting subtly comments on class distinctions, social etiquette, and the anonymous yet shared experience of city life. The work was exhibited at the British Institution in 1859 and was well-received, praised for its truthfulness and its engaging subject matter. It demonstrated Egley's ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and to imbue them with narrative interest, a skill likely honed during his collaborations with Frith. The painting's success cemented Egley's reputation as a keen observer of contemporary manners.

Engagement with Literary Themes and The Lady of Shalott

Despite his success with contemporary genre scenes, Egley never entirely abandoned literary subjects. Throughout his career, he returned to the rich well of English literature for inspiration. Shakespeare remained a favorite, but he also explored themes from other poets and writers. One notable literary painting is his interpretation of Alfred, Lord Tennyson's immensely popular poem, "The Lady of Shalott."

Tennyson's poem, first published in 1833 and revised in 1842, tells the tragic story of a woman cursed to weave a web and view the world only through a mirror. When she defies the curse to look directly at Sir Lancelot, the mirror cracks, and she meets her doom. The poem's themes of art, isolation, love, and fate captivated the Victorian imagination and were painted by numerous artists, including prominent Pre-Raphaelites like William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as well as later artists like John William Waterhouse.

Egley's version of The Lady of Shalott (circa 1858) depicts the moment the curse comes upon her. His treatment is characterized by a rich, somewhat somber palette and a focus on the dramatic intensity of the scene. The Lady is shown recoiling as the threads of her tapestry fly about her, the mirror cracking behind her. Egley's style in such literary pieces often retained a certain illustrative quality, emphasizing narrative clarity. While perhaps not as symbolically dense as some Pre-Raphaelite interpretations, his rendition effectively conveys the emotional turmoil of the moment. This continued engagement with literary themes demonstrates the breadth of Egley's artistic interests and his connection to the prevailing Romantic sensibilities of the era.

The Pre-Raphaelite Connection

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, represented a significant artistic movement in Victorian England. They advocated for a return to the detailed realism, intense colors, and serious subjects of art before Raphael, rejecting the academic conventions they felt had stifled British painting. Key tenets included truth to nature, meticulous detail, bright, clear colors applied to a wet white ground, and often, complex symbolism.

While William Maw Egley was not a formal member of the PRB, his work shows undeniable, albeit nuanced, connections to their aesthetic. His commitment to detailed rendering, evident in works like Omnibus Life in London, aligns with the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on close observation. Furthermore, his palette, often described as featuring "hard-edge details and acid color tones," echoes the bright, sometimes startling, hues favored by the PRB. This is particularly noticeable when compared to the more muted, bituminous palettes common in earlier Victorian painting.

However, Egley's relationship with Pre-Raphaelitism was not one of straightforward adoption. Art historians have noted that while he embraced certain superficial aspects, his underlying approach sometimes differed. For instance, his handling of light and perspective, while competent, occasionally leaned more towards established, even somewhat "medievalizing," techniques rather than the radical, almost photographic, naturalism pursued by Hunt or the early Millais. Some critics felt his figures could be somewhat stiff or "clumsy," lacking the psychological depth or the idealized beauty often found in the work of Rossetti or later Pre-Raphaelite associates like Edward Burne-Jones or Arthur Hughes.

Despite these distinctions, the PRB's influence was pervasive in the Victorian art world, and Egley, like many of his contemporaries, absorbed elements of their style. His work can be seen as part of a broader trend towards greater realism and brighter coloration that the Pre-Raphaelites helped to popularize. He shared with them an interest in literary subjects, though his interpretations were often less overtly moralizing or symbolic than those of the core PRB members.

A Pioneer of the Christmas Card

Beyond his paintings, William Maw Egley is associated with an interesting piece of social and cultural history: the Christmas card. While the claim to the "first" Christmas card is often attributed to Sir Henry Cole, who commissioned John Callcott Horsley to design a card in 1843, there is evidence suggesting Egley produced a Christmas card even earlier.

According to some records, Egley designed a card in 1842. This card reportedly depicted a festive scene incorporating elements like a Christmas dinner, dancers, ice skaters, and a scene of charity with the poor receiving gifts. The greeting was the now-familiar "A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You." If this dating is accurate, it would predate the Cole-Horsley card by a year, making Egley a significant, if perhaps unintentional, pioneer in this popular tradition.

The emergence of the Christmas card in the 1840s reflects broader societal changes, including the popularization of Christmas traditions (partly due to the influence of Prince Albert), advancements in printing technology (like lithography), and the introduction of the Penny Post in 1840, which made sending greetings more affordable. Egley's involvement, whether as the absolute first or simply an early adopter, highlights his engagement with contemporary cultural trends and his versatility as an artist.

Style, Technique, and Critical Reception

William Maw Egley's artistic style evolved over his long career but retained certain consistent characteristics. His early training under his miniaturist father likely instilled in him a penchant for precision and detail, which remained evident throughout his oeuvre. His color palette, as mentioned, often featured bright, clear tones, sometimes described as "acidic," distinguishing his work from the more somber academic painting of the time.

He was particularly adept at genre scenes, capturing the nuances of Victorian life with a keen observational eye and often a gentle humor. Works like Omnibus Life in London showcase his skill in composing multi-figure scenes, managing perspective, and rendering varied textures and costumes. His literary paintings, while perhaps less innovative than his contemporary subjects, demonstrated his narrative abilities and his connection to the Romantic literary tastes of the period.

Despite his prolific output – he is said to have produced over a thousand paintings – and regular exhibitions at prestigious venues like the Royal Academy of Arts (from 1843 to 1898) and the British Institution, Egley's critical reception during his lifetime was somewhat mixed. While his technical skill and the engaging nature of his subjects were often acknowledged, he was not always ranked among the foremost innovators of his day. Some contemporary critics found his figures occasionally stiff or his compositions lacking the profound depth or emotional intensity of artists like Millais or Hunt. The term "clumsy" was sometimes applied, perhaps referring to a certain lack of grace or idealization in his figures when compared to more academic or romantically inclined painters.

Ford Madox Brown, an artist closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelites and known for his own detailed social realist works like Work (1852-65), commented on Egley's Omnibus Life in London. While acknowledging its cleverness and popularity, Brown's diary entry suggests a somewhat critical view of its execution, perhaps finding it more illustrative than profoundly artistic in the way he conceived his own ambitious canvases.

Later Life and Legacy

William Maw Egley continued to paint and exhibit well into his later years, remaining a consistent presence in the London art scene. He passed away on February 20, 1916, at the age of 89 or 90, having witnessed the entirety of the Victorian era and the dawn of the modern age.

In the decades following his death, Egley, like many Victorian genre painters, experienced a period of relative obscurity as artistic tastes shifted dramatically with the rise of modernism. However, the latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century have seen a renewed scholarly and public interest in Victorian art. In this context, Egley's work has been re-evaluated.

His paintings are now recognized for their valuable contribution to our understanding of Victorian society. Omnibus Life in London, in particular, is frequently reproduced and discussed as a key image of 19th-century urban life. His detailed depictions of interiors, costumes, and social interactions provide a rich visual record of the period. Art historians appreciate his role as a chronicler of his times, capturing both the everyday and the imaginative life of Victorian England. While he may not be considered a revolutionary figure, his skill, diligence, and the sheer breadth of his output mark him as a significant practitioner within the Victorian art world. His connection to figures like William Powell Frith and his absorption of Pre-Raphaelite influences further situate him within the important artistic dialogues of his era. Artists like Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer, who also tackled social themes, albeit often with a more overtly critical or sentimental edge, followed in a tradition of social observation that Egley also participated in.

Conclusion: An Enduring Victorian Vision

William Maw Egley was an artist deeply embedded in the Victorian era. His work reflects its literary preoccupations, its burgeoning urban life, its class consciousness, and its evolving artistic tastes. From his early literary illustrations to his celebrated genre scenes like Omnibus Life in London, and his participation in the nascent tradition of the Christmas card, Egley consistently engaged with the culture of his time.

Influenced by his father, by collaborators like William Powell Frith, and by the pervasive spirit of Pre-Raphaelitism, he forged a style characterized by meticulous detail, bright colors, and a keen observational humor. Though perhaps not reaching the heights of fame or critical adulation achieved by some of his contemporaries, William Maw Egley left behind a substantial body of work that continues to inform and delight. He remains an important figure for understanding the diverse artistic landscape of Victorian Britain, a diligent chronicler whose canvases offer a window into a bygone world, rendered with skill and an evident affection for its myriad human stories.