Introduction

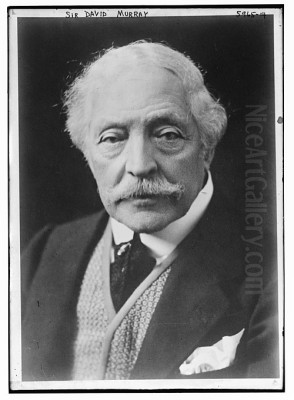

Sir David Murray RA stands as a significant figure in the annals of British landscape painting, particularly celebrated for his evocative depictions of his native Scotland and the gentler terrains of Southern England. Born in the industrial heart of Glasgow in 1849 and passing away in London in 1933, Murray's life spanned a period of immense change, both socially and artistically. He rose from humble beginnings to become a respected member of the Royal Academy and a Knight of the Realm, leaving behind a substantial body of work cherished for its atmospheric beauty, fidelity to nature, and often sun-drenched optimism. His journey reflects a dedication to capturing the essence of the British landscape, earning him considerable acclaim during his lifetime and a lasting place in the history of Scottish and British art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Glasgow

David Murray was born on January 29, 1849, in Glasgow, Scotland. His origins were modest; his father was a shoemaker, and the path to a career in the arts was not immediately apparent. For eleven formative years, the young Murray worked diligently in the commercial sector, employed by two different mercantile firms. This practical grounding in the world of business might seem distant from the life of an artist, but it perhaps instilled in him a discipline and work ethic that would serve him well in his future endeavours.

Despite the demands of his day job, Murray's passion for art could not be suppressed. He dedicated his evenings to honing his artistic skills, enrolling at the renowned Glasgow School of Art. There, he studied under the tutelage of Robert Greenlees, a respected master at the institution. This period of part-time study laid the crucial foundation for his technical abilities and artistic vision. The burgeoning art scene in Glasgow, which would soon give rise to the famed 'Glasgow Boys', provided a stimulating, if challenging, environment for an aspiring painter.

Around 1875, Murray made the pivotal decision to abandon his commercial career and devote himself entirely to painting. This leap of faith marked the true beginning of his professional artistic journey. He began exhibiting his work, focusing initially on the landscapes of his homeland. The rugged beauty of the Scottish Highlands, the tranquil lochs, and the winding rivers provided ample inspiration. His early works started to gain attention, signalling the arrival of a promising new talent on the Scottish art scene.

His growing reputation in Scotland was formally recognized in 1881 when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy (ARSA). This prestigious acknowledgement from the leading art institution in Scotland was a significant milestone, validating his decision to pursue art full-time and boosting his standing within the artistic community. It was a testament to the quality and appeal of his landscape paintings, which were already demonstrating a keen eye for detail and a sensitivity to the nuances of the natural world.

The Move to London and Academic Success

Seeking broader horizons and greater opportunities, David Murray made a decisive move in 1882, relocating from Glasgow to London, the vibrant epicentre of the British art world. This transition proved highly successful. London offered access to major galleries, influential patrons, and a larger, more diverse community of artists. Murray quickly began to make his mark, exhibiting regularly and gaining positive notice from critics and the public alike.

His arrival in London coincided with a period where landscape painting enjoyed considerable popularity, though tastes were evolving with the influence of continental movements like Impressionism. Murray, however, largely continued to develop his own distinct style, rooted in careful observation and a love for the specific character of the British countryside. His ability to capture light and atmosphere, combined with pleasing compositions, resonated with the exhibition-going public.

A major breakthrough occurred in 1884 with his painting My Love has gone a-Sailing. Exhibited at the Royal Academy, this work garnered significant attention and was subsequently purchased by the Chantrey Bequest. The Chantrey Bequest was a prestigious fund administered by the Royal Academy Council, established to acquire works of art "of the highest merit" for the nation. This purchase was a considerable honour, bringing Murray's work into the national collection (now part of the Tate collection) and significantly enhancing his reputation.

The momentum continued, and Murray's standing within the London art establishment grew steadily. In 1891, he achieved another significant accolade when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This placed him firmly within the ranks of the nation's leading artists. His election recognized his consistent contributions to the Academy's exhibitions and the high quality of his landscape painting. He was joining an institution peopled by esteemed figures, contemporaries like the popular landscape painter Benjamin Williams Leader, the classical revivalist Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and the influential portraitist John Singer Sargent.

His ascent within the Royal Academy culminated in 1905 when he was elected a full Royal Academician (RA). This was the highest honour bestowed by the Academy, signifying his established position as a master in his field. As an RA, Murray took on a more active role in the Academy's affairs, serving on its council and contributing to its exhibitions for many more years. His journey from a Glasgow merchant's office to the hallowed halls of the Royal Academy was complete, a testament to his talent, perseverance, and the widespread appeal of his art.

The Heart of the Landscape: Murray's Subjects and Style

David Murray dedicated his artistic life primarily to landscape painting. His deep connection to the natural world is evident throughout his extensive body of work. While he is often categorized as a Scottish painter due to his origins and frequent depictions of his homeland, his artistic gaze also embraced the landscapes of Southern England and, later in his career, parts of France, particularly Picardy.

His Scottish subjects often focused on the dramatic beauty of the Highlands, particularly the Trossachs region, known for its lochs, mountains, and association with Romantic literature, notably the works of Sir Walter Scott. He painted the River Tay and its surroundings extensively, capturing the unique light and atmosphere of these northern landscapes. These works often convey a sense of grandeur and wildness, reflecting the powerful, untamed aspects of nature. His approach was distinct from some of his Scottish contemporaries like William McTaggart, whose work often featured more turbulent seascapes and a looser, more proto-Impressionist style.

Upon moving south, Murray found new inspiration in the gentler, more pastoral scenery of England. The rolling hills of the Sussex Downs, the picturesque villages, and the tranquil rivers provided a different palette and mood. Works depicting Corfe Castle in Dorset, the meadows of Hampshire, or the iconic scenery around Constable's Flatford Mill (as seen in his In the Country of Constable) showcase his versatility. These English landscapes often possess a sunnier disposition, filled with light and a sense of peaceful cultivation, contrasting with the sometimes brooding majesty of his Scottish scenes.

Later in his career, Murray frequently travelled to Picardy in Northern France. The wide, open fields, poplar-lined rivers, and rural villages of this region offered new motifs. His French landscapes often exhibit a broader handling of paint and a heightened interest in capturing fleeting effects of light and weather, perhaps showing a subtle absorption of Impressionist sensibilities, though he never fully embraced the Impressionist technique favoured by artists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro. His focus remained on representational accuracy combined with atmospheric effect.

Murray's style is characterized by its detailed observation, strong compositional structure, and a particular skill in rendering light and atmosphere. He often favoured bright, clear conditions, earning a reputation for his sunlit scenes, filled with "sun-steep'd" meadows and sparkling water. His brushwork, while capable of fine detail, could also be broad and confident, especially in his later works, effectively conveying the textures of foliage, water, and sky. He aimed to present nature faithfully but imbued with a sense of poetry and often, a cheerful serenity. He remained largely independent of radical artistic movements, finding his niche within the established traditions of British landscape painting, alongside contemporaries like Alfred East, another landscape specialist who also achieved considerable recognition.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Throughout his long and productive career, Sir David Murray created a vast number of paintings, many of which were widely exhibited and admired. Several works stand out as particularly representative of his style and achievement.

My Love has gone a-Sailing (1884) remains one of his most famous works, largely due to its early acquisition by the Chantrey Bequest. This painting, depicting a coastal scene likely inspired by his Scottish roots, combines landscape elements with a subtle narrative suggestion implied by the title. Its purchase cemented his early reputation in London and showcased his ability to create pictures with both visual appeal and emotional resonance.

Sunset at Corfe Castle, Dorset is another well-regarded work, capturing the iconic ruins bathed in the warm glow of the setting sun. This painting exemplifies his skill in rendering atmospheric effects and his appreciation for the picturesque qualities of the English landscape. The dramatic lighting and historical subject matter made it a popular image, demonstrating his ability to connect with prevailing tastes for romantic scenery.

Sun Steep'd Noon represents a recurring theme in Murray's work – the depiction of the British countryside bathed in bright, midday sunlight. These paintings often feature lush meadows, meandering rivers, and grazing cattle, conveying a sense of idyllic pastoral peace. They highlight his mastery of light and his optimistic view of nature, a characteristic that distinguished him from artists focusing on more sombre or dramatic natural phenomena.

Other notable works further illustrate the breadth of his subjects and his consistent quality. In the Country of Constable pays homage to one of the great masters of English landscape painting, John Constable, while showcasing Murray's own interpretation of the Suffolk scenery. The River Road, Picardy Pastoral, Meadowsweet, and The White Mill are titles that suggest his engagement with different locations and aspects of the rural landscape, from tranquil riverbanks to the agricultural heartlands of France.

His contributions to the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions were numerous, often featuring large-scale landscapes that commanded attention. While perhaps not revolutionary in technique compared to the Post-Impressionists or emerging modernist trends, Murray's works consistently found favour with the public and critics who appreciated his technical skill, his dedication to the beauty of the British Isles, and his ability to evoke the spirit of place. His paintings offered a reassuring vision of nature's enduring charm during a time of rapid industrialization and social change.

A Leading Figure in Art Institutions

Sir David Murray's influence extended beyond his own canvases; he became a prominent figure within several key British art institutions. His long association with the Royal Academy of Arts in London was central to his career. Having been elected an Associate in 1891 and a full Academician in 1905, he was deeply integrated into its structure. He served on its Council and was a regular and significant contributor to its influential Summer Exhibitions for decades. The RA was the pinnacle of the established art world in Britain, and Murray's position within it underscored his status. He exhibited alongside the leading artists of the day, from academicians upholding traditional values like Sir Edward Poynter (RA President for many years) to those exploring slightly more modern approaches like George Clausen.

His Scottish roots remained important, and he maintained his connection with the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in Edinburgh, having been elected an Associate early in his career. Although based in London, he continued to be recognized as a major Scottish painter, contributing to the artistic life north of the border. The Glasgow art scene, where he started, had also flourished, with the international success of the 'Glasgow Boys' like Sir John Lavery, James Guthrie, and George Henry, demonstrating the vitality of Scottish painting during this period. Murray, while charting his own course, was part of this broader flourishing of Scottish talent.

Murray was also highly active in the world of watercolour painting. He was elected President of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI) in 1917. The RI was another significant exhibiting society, dedicated to promoting the medium of watercolour. His presidency, which he held for a number of years (the provided text mentions James Linton succeeding him, likely referring to Sir James Linton, a former RI President, suggesting Murray's term ended before his death, though sources often cite him as President in 1917), demonstrated his mastery across different media and his leadership within the artistic community. Watercolour painting had a rich tradition in Britain, tracing back to artists like J.M.W. Turner, and Murray contributed significantly to its continued vitality.

Furthermore, his membership in the Glasgow Art Club connected him to the artistic fraternity in his home city. These affiliations show an artist deeply engaged with the professional structures of the art world, contributing to their governance and participating fully in their activities. His institutional roles complemented his painting practice, making him a well-respected and central figure in the British art establishment of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras.

Context and Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Sir David Murray's contribution, it's essential to place him within the artistic context of his time. He worked during a period of transition and diversification in British art. The High Victorian era, with its emphasis on narrative, detail, and moralistic themes, was gradually giving way to new influences and concerns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Landscape painting remained immensely popular, seen as a quintessential British genre tracing its lineage back to giants like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner. Murray operated within this strong tradition, focusing on the faithful yet poetic representation of specific locales. He shared the market with other successful landscape specialists like Benjamin Williams Leader and Alfred East, who also catered to the public's appetite for picturesque views of the British countryside. These artists often achieved considerable popular and financial success through RA exhibitions and the sale of reproductions.

However, the late 19th century also saw the arrival of new artistic ideas from the Continent, most notably French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley had pioneered a new way of seeing and painting, emphasizing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and subjective perception, often using broken brushwork and a brighter palette. While some British artists, like Philip Wilson Steer, embraced these innovations, Murray, like many of his RA colleagues, maintained a more conservative approach rooted in academic tradition and detailed observation. While his later work shows a looser handling and a brighter palette, particularly in his French scenes, it stopped short of full Impressionist technique.

In Scotland, the situation was also dynamic. The Glasgow Boys (including Lavery, Guthrie, Henry, E.A. Walton, and others) were gaining international acclaim for their distinctive blend of realism, decorative qualities, and often plein-air techniques, influenced by French naturalist painters like Jules Bastien-Lepage. While Murray was a contemporary and originated from Glasgow, his style and career trajectory differed from the core members of this group. He pursued a more traditional path through the London-based Royal Academy system.

Murray also worked alongside prominent figures in other genres at the Royal Academy, such as the aforementioned portraitist John Singer Sargent, the neo-classical painters Lord Leighton and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and narrative painters like Sir Edward Poynter. The RA exhibitions presented a diverse, if largely traditional, cross-section of British art. Murray's consistent focus on landscape provided a popular and enduring element within this mix. His work offered an appealing vision of rural stability and beauty, a comforting counterpoint to the rapid modernization and social anxieties of the era.

Later Years and Legacy

David Murray continued to paint prolifically throughout the early decades of the 20th century. His dedication to his craft and his established reputation ensured his continued prominence in the British art world. In recognition of his significant contributions to art, he received a knighthood in 1918, becoming Sir David Murray RA. This honour solidified his position as a respected member of the national establishment.

He remained actively involved with the Royal Academy and the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours. Despite the rise of Modernism and the avant-garde movements that challenged traditional artistic values, Murray's landscape paintings retained their appeal for a significant segment of the public and collectors. His work continued to be exhibited regularly, and he maintained his studio practice with vigour.

Sir David Murray never married and, according to accounts, lived for many years in bachelor apartments in London, first perhaps near Portobello Road as mentioned in initial notes, and later, more famously, at 1 Langham Chambers, Portland Place. His life appears to have been centred around his art, his travels in search of subjects, and his involvement in the art institutions he belonged to.

He passed away on November 14, 1933, in Marylebone, London, at the age of 84. He left behind a substantial legacy, both in terms of his extensive body of work and his role within the art institutions of his time. His paintings are held in numerous public collections, including the Tate Britain, the Royal Academy of Arts, the Glasgow Museums, and various regional galleries throughout the UK. His work is also represented in international collections, such as the National Gallery of Victoria in Australia.

While artistic tastes shifted dramatically during and after his lifetime, there has been a renewed appreciation for the skill and charm of late Victorian and Edwardian landscape painting. Sir David Murray's work is valued for its technical accomplishment, its evocative portrayal of the British landscape, its mastery of light and atmosphere, and its often uplifting and serene vision of nature. He remains an important figure for understanding the mainstream of British art during his era.

Conclusion

Sir David Murray RA was a painter deeply devoted to the landscapes of Britain and, to a lesser extent, France. From his early studies in Glasgow to his long and successful career centred in London, he consistently sought to capture the beauty, light, and atmosphere of the natural world. His rise through the ranks of the Royal Academy, culminating in a knighthood, attests to the high regard in which he was held by the art establishment and the public. Works like My Love has gone a-Sailing and his numerous sunlit depictions of Scottish glens and English downs secured his reputation. While not an avant-garde innovator, Murray excelled within the tradition of representational landscape painting, creating a significant body of work characterized by technical skill, careful observation, and an enduring appeal. He remains a key figure in the story of Scottish art and the broader narrative of British landscape painting in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.