Derwent Lees (1884/5–1931) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century British and Australian art. An artist whose career, though tragically curtailed by illness, burned brightly with a distinctive Post-Impressionist vision, Lees forged a unique path, absorbing influences from his native Australia, his studies in Paris, and his immersion in the vibrant London art scene, particularly at the Slade School of Fine Art. His close association with fellow artists James Dickson Innes and Augustus John, especially during their formative painting expeditions in Wales, produced a body of work celebrated for its intense colour, emotional depth, and innovative approach to landscape.

Early Life and Formative Experiences

Born in Hobart, Tasmania, around 1884 or 1885, Richard Murray Derwent Lees was the son of a bank manager. His early life in Australia provided him with initial encounters with a unique and dramatic natural environment, a sensibility that would later inform his landscape painting. The family subsequently moved to Melbourne, where Lees received his secondary education at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School. A pivotal and tragic event occurred during his youth: a riding accident resulted in the loss of his right foot, which was thereafter replaced by an artificial limb. This physical challenge, however, did not deter his pursuit of an artistic career.

Lees attended the University of Melbourne, though his formal art training in Australia was relatively limited compared to his later European studies. The artistic milieu in Australia at the turn of the century was still largely influenced by the Heidelberg School, a group of Australian Impressionists like Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, and Charles Conder, who had adapted French Impressionist techniques to capture the unique light and atmosphere of the Australian bush. While Lees would later develop a more Post-Impressionist style, this early exposure to landscape painting and the pursuit of national artistic identity likely played a role in his development.

Parisian Sojourn and the Slade School of Art

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Derwent Lees, like many aspiring artists of his generation, travelled to Europe. He spent some time in Paris around 1905, a city that was then the undisputed epicentre of the avant-garde. This period would have exposed him to the full force of Impressionism and the burgeoning Post-Impressionist movements. The works of Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and Georges Seurat were becoming increasingly visible and discussed, challenging traditional academic art and opening up new possibilities for colour, form, and emotional expression.

Following his Parisian experience, Lees enrolled at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London in 1905, remaining there until 1907. The Slade, under the professorship of Fred Brown, and with influential teachers like Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer, was a crucible of talent and a significant force in British art education. It fostered a rigorous approach to drawing while also encouraging individual expression. Tonks, in particular, was a formidable figure, known for his exacting standards and his emphasis on draughtsmanship. Steer, a leading figure of British Impressionism, would have provided a direct link to more modern painterly concerns.

At the Slade, Lees was part of an exceptionally gifted generation of students. His contemporaries included Augustus John (who had studied there slightly earlier but remained a dominant influence), William Orpen, Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman, Gwen John (Augustus's sister), Wyndham Lewis, Paul Nash, C.R.W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler, and David Bomberg. This environment was intellectually stimulating and artistically competitive, pushing students to explore new directions. Lees excelled, winning several prizes, including the Summer Competition Prize in 1907 and a figure painting prize in 1908. His talent was recognized early, and he was appointed Assistant Drawing Master at the Slade in 1908, a position he held until 1918.

The Arenig School: A Welsh Rhapsody

One of the most significant and artistically fruitful periods of Derwent Lees's career was his association with fellow artists James Dickson Innes (1887-1914) and Augustus John (1878-1961). This trio, sometimes referred to as the "Arenig School" or the "Welsh Realists," though their style was far from traditional realism, embarked on several painting expeditions to North Wales, particularly around the Arenig Fawr mountain, between 1910 and 1913.

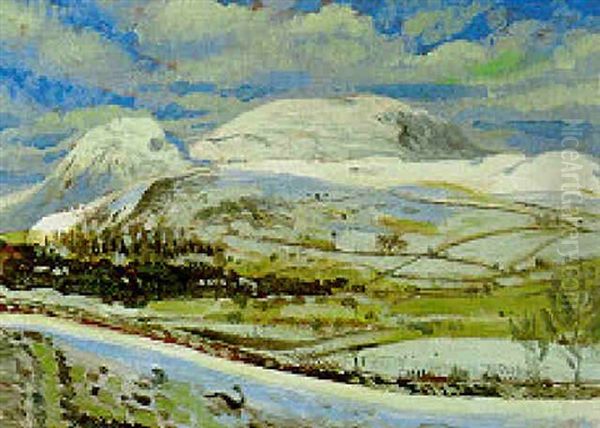

Innes, a charismatic and tragically short-lived painter suffering from tuberculosis, had a profound passion for the Welsh landscape. He introduced Lees to the rugged beauty of this region. Together with the more established Augustus John, they would often stay in a small cottage, the Ffrwd-yr-hedydd, near Rhyd-y-fen, and paint en plein air, directly capturing the dramatic light, sweeping vistas, and intense colours of the mountains and valleys. Their work from this period is characterized by a heightened emotional response to nature, expressed through vibrant, often non-naturalistic colours, simplified forms, and bold, expressive brushwork.

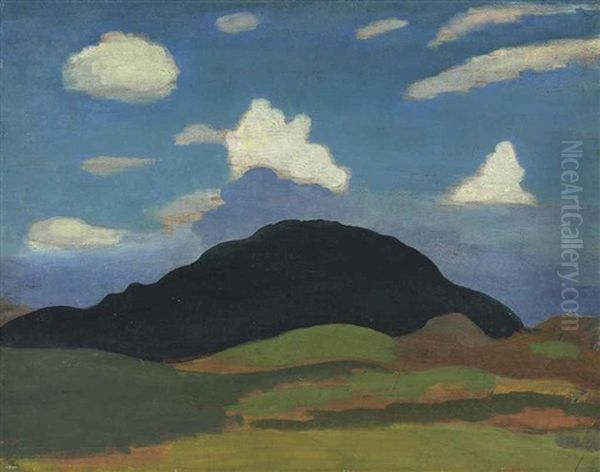

The influence of Post-Impressionism, particularly the Fauvist use of colour and the expressive intensity of Van Gogh, is evident in their Welsh landscapes. Lees, Innes, and John shared a common artistic language during these years, yet each retained his individuality. Innes's work often possessed a delicate, almost ethereal quality, while John's figures and landscapes were typically more robust and monumental. Lees's paintings from this period, such as "The Yellow Skirt" (featuring his future wife, Edith Harriet Price, known as "Lyndra"), often combine figures with the landscape, imbued with a lyrical and decorative quality. His landscapes, like "Arenig, North Wales" (c. 1913), showcase his ability to translate the raw energy of the scenery into compelling, colour-saturated compositions.

This period of intense creativity and camaraderie was, however, brief. Innes's declining health and eventual death in 1914, followed by the outbreak of World War I, brought an end to these shared Welsh adventures. Nevertheless, the body of work produced by Lees, Innes, and John in North Wales remains a remarkable chapter in British Post-Impressionism, demonstrating a powerful and original response to the landscape.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Derwent Lees's artistic style is firmly rooted in Post-Impressionism, but with a distinctive personal inflection. He was less concerned with the analytical deconstruction of form seen in Cézanne or the pointillism of Seurat, and more aligned with the expressive use of colour and line found in Van Gogh, Gauguin, and the Fauves like Henri Matisse and André Derain. His paintings are characterized by their luminous, often high-keyed palettes, where colours are chosen for their emotional and decorative impact rather than strict adherence to naturalism.

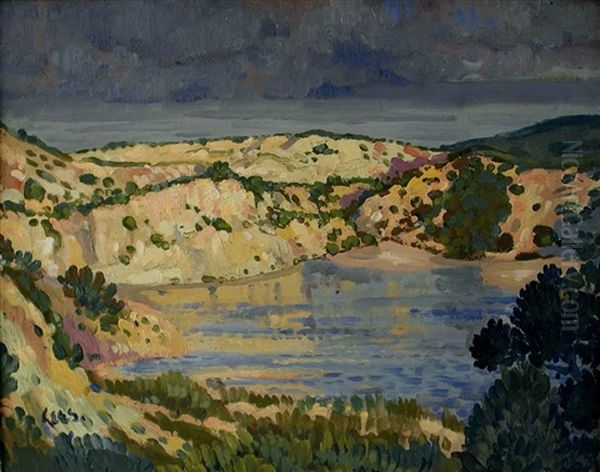

His brushwork is typically vigorous and direct, contributing to the overall vibrancy of his surfaces. He often employed simplified forms and strong outlines, giving his compositions a sense of clarity and decorative unity. While landscape was his primary subject, particularly the mountains of Wales and later the sun-drenched scenery of the South of France (such as Collioure, a favourite spot for Matisse and Derain), Lees was also an accomplished portraitist. His portraits, like those of his wife Lyndra, often share the same qualities of bold colour and expressive handling found in his landscapes.

A recurring theme in Lees's work is the harmonious integration of figures within the landscape. These figures are not mere accessories but integral parts of the composition, often imbued with a sense of quiet contemplation or lyrical grace. His work often evokes a strong sense of place, capturing the specific atmosphere and character of the locations he painted. Whether depicting the rugged grandeur of Arenig Fawr or the bright sunlight of the Mediterranean coast, Lees sought to convey an intense personal response to the world around him.

The influence of Japanese prints, which had a profound impact on many Post-Impressionist artists, can also be discerned in some of Lees's compositions, particularly in their flattened perspectives, decorative patterning, and asymmetrical arrangements. He was adept at creating a strong sense of design, balancing areas of bold colour with dynamic lines.

Key Works and Exhibitions

Several works stand out as representative of Derwent Lees's artistic achievement. "Pear Tree in Blossom" (c. 1910-1912), now in the collection of the Tate, London, is a quintessential example of his lyrical Post-Impressionism. The painting depicts a blossoming pear tree against a backdrop of simplified landscape forms, rendered in a palette of fresh, vibrant colours. The brushwork is energetic, and the overall effect is one of joyous celebration of nature. It is considered one of the significant works of British landscape painting from this era.

"Capel-y-ffin" (c. 1912-13), depicting a scene in the Welsh valleys, showcases his ability to capture the unique light and atmosphere of the region. The strong colours and bold forms convey the rugged beauty of the landscape, while also imbuing it with a sense of romanticism. His paintings of Arenig Fawr, often painted alongside Innes, are powerful testaments to their shared artistic vision and their deep connection to this particular mountain.

Lees exhibited regularly during his career. He was a member of the New English Art Club (NEAC), an exhibiting society that provided an alternative to the Royal Academy and was more receptive to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist tendencies. His work was also included in significant exhibitions of modern art, such as the influential Armory Show (International Exhibition of Modern Art) in New York in 1913, which introduced American audiences to European avant-garde art. His inclusion in such an exhibition underscores his standing within the modernist currents of the time. He also exhibited at the Goupil Gallery and the Chenil Galleries in London.

His works are held in numerous public collections, including the Tate Britain, the National Museum Wales, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the National Gallery of Victoria (to which he reportedly made significant donations, reflecting his connection to his Australian roots and perhaps his involvement in the Australian republican movement), and the Australian National Gallery.

War Artist and Later Years

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the artistic landscape in Britain underwent significant changes. Many artists became involved in the war effort, either as soldiers or as official war artists. Derwent Lees served as an official war artist, tasked with documenting aspects of the conflict. While this period is part of his biography, his output as a war artist is perhaps less central to his overall artistic identity than his pre-war landscapes.

Tragically, Derwent Lees's promising career was cut short by mental illness. He began to suffer from schizophrenia, and from 1918 onwards, he spent the remainder of his life in various mental institutions, including West Park Mental Hospital in Epsom, Surrey. This debilitating illness effectively ended his painting career when he was still in his thirties. He died in hospital on March 28, 1931, at the relatively young age of 46 or 47.

The premature end to his artistic production is a poignant aspect of his story. Given the brilliance and originality of his work up to 1918, one can only speculate on how his art might have evolved had he been able to continue painting.

Connections and Contemporaries

Derwent Lees's artistic journey was interwoven with many of the key figures and movements of his time. His closest artistic collaborators were undoubtedly James Dickson Innes and Augustus John, with whom he formed the core of the Arenig School. Their shared explorations in Wales represent a distinct and vibrant offshoot of British Post-Impressionism.

Through the Slade School, he was connected to a generation of artists who would go on to shape British art in the 20th century. Figures like Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, fellow Slade alumni, became central to the Camden Town Group, which, under the influence of Walter Sickert and Lucien Pissarro, explored Post-Impressionist techniques to depict scenes of urban life. While Lees's focus was primarily landscape, he shared with these artists an interest in bold colour and expressive form.

The broader context of British art at the time was significantly shaped by Roger Fry's groundbreaking exhibitions, "Manet and the Post-Impressionists" in 1910 and the "Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition" in 1912. These exhibitions introduced artists like Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, and Picasso to a wider British audience and had a profound impact on younger artists, including Lees. His work clearly reflects the liberating influence of these Continental masters.

Other notable contemporaries in the British art scene included members of the Bloomsbury Group, such as Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, who were also exploring Post-Impressionist aesthetics. While direct collaborations might not have been extensive, Lees operated within this milieu of artistic ferment and experimentation. Artists like Matthew Smith, known for his rich colour and sensuous handling of paint, also shared a similar Post-Impressionist sensibility. Even earlier figures like Philip Wilson Steer, one of his teachers, provided a bridge between British Impressionism and the newer movements.

Legacy and Conclusion

Derwent Lees's legacy is that of a gifted and original artist whose career, though brief, made a significant contribution to British and Australian art. His vibrant Post-Impressionist landscapes, particularly those created in Wales and the South of France, are celebrated for their intense colour, emotional resonance, and decorative power. His association with Innes and John during the Arenig period produced some of the most compelling British landscape paintings of the early 20th century.

Despite the tragic curtailment of his career due to mental illness, the body of work he produced remains a testament to his unique vision. He successfully synthesized influences from European Post-Impressionism with a personal response to the landscapes he encountered, creating art that is both aesthetically pleasing and emotionally engaging. His role as an educator at the Slade, albeit for a limited time, also indicates the respect he commanded among his peers.

Today, Derwent Lees is recognized as an important figure in the transition from Impressionism to modernism in British art. His paintings continue to be admired for their luminous beauty and their bold, expressive qualities, securing his place as a distinctive voice in the art of his time. His Australian origins add another layer to his story, positioning him as one of several expatriate Australian artists who made their mark on the international stage, bringing a fresh perspective to the European art world while also contributing to the cultural heritage of their homeland. His life and art serve as a poignant reminder of a brilliant talent whose full potential was tragically unfulfilled, yet whose achievements continue to shine.