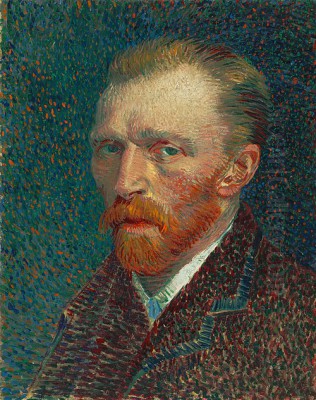

Vincent van Gogh stands as one of the most iconic and influential figures in the history of Western art. A Dutch Post-Impressionist painter, his life was a tumultuous journey marked by fervent creativity, profound emotional struggles, and a tragic lack of recognition during his lifetime. Born on March 30, 1853, in Groot Zundert, North Brabant, Netherlands, and dying prematurely on July 29, 1890, in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, Van Gogh left behind an astonishing body of work that continues to captivate and move audiences worldwide. His paintings, characterized by bold colors, dramatic brushwork, and intense emotional honesty, bridge the gap between Impressionism and the modern art movements of the 20th century, particularly Fauvism and Expressionism. This article delves into the life, art, struggles, and enduring legacy of this extraordinary artist.

Early Life and Vocational Crises

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born into a family with ties to both religion and art. His father, Theodorus van Gogh, was a pastor in the Dutch Reformed Church, and several uncles were art dealers. Vincent was actually the second child of his parents to bear the name; the first Vincent was stillborn exactly one year before his birth, a fact some biographers suggest cast a shadow over his early life. He grew up serious, quiet, and thoughtful. Early on, he showed an interest in drawing, but his path towards becoming an artist was far from direct.

Before dedicating himself to art, Van Gogh attempted several other vocations. At sixteen, he began working for the art dealership Goupil & Cie., a firm where his uncle Cent had been a partner. He worked in their branches in The Hague, London, and Paris. This period exposed him to a wide range of art but also led to disillusionment, partly due to the commercial aspects of the art world and partly due to personal disappointments, including unrequited love. He was dismissed from Goupil in 1876.

Following his dismissal, Van Gogh sought a more spiritual path, reflecting his father's calling. He worked briefly as a supply teacher in Ramsgate and Isleworth in England, where he also delivered sermons. Deeply religious, he then felt a strong urge to serve the poor and became a lay preacher in the Borinage, a bleak coal-mining district in Belgium, in 1879. He lived in poverty among the miners, sharing their hardships, but his overly zealous approach and literal interpretation of Christian teachings led church authorities to dismiss him. This failure marked another profound crisis in his life.

The Decision to Become an Artist

It was only after these vocational failures, around 1880, at the age of 27, that Vincent van Gogh decided to fully commit himself to art. Encouraged by his younger brother Theo, who worked for Goupil & Cie. in Paris and would become his lifelong confidant and financial supporter, Vincent began to seriously study drawing and painting. He briefly attended the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels but was largely self-taught, learning through diligent practice, studying manuals, copying prints, and observing the work of artists he admired.

His brother Theo's unwavering support was crucial. Theo not only provided Vincent with a monthly stipend that allowed him to survive and purchase art supplies but also offered invaluable emotional encouragement and acted as his primary connection to the art world. Their extensive correspondence, numbering over 600 letters from Vincent to Theo, provides an intimate and detailed record of Vincent's thoughts, feelings, artistic development, and daily struggles.

Formative Years: The Dutch Period

Van Gogh's early artistic years, spent primarily in the Netherlands (Etten, The Hague, Drenthe, and Nuenen) between 1880 and 1885, were characterized by a somber palette and a focus on depicting the lives of peasants and rural laborers. He was deeply influenced by the realism of artists like Jean-François Millet and the dramatic chiaroscuro of Dutch Masters such as Rembrandt. He worked tirelessly on mastering drawing, particularly the human figure, often using local peasants as models.

His subjects during this period included weavers, farmers, and miners, rendered in dark, earthy tones – blacks, browns, and dark greens. He sought to portray the harsh realities and dignity of peasant life. The culmination of this Dutch period is arguably The Potato Eaters (1885). Painted in Nuenen, this work depicts a peasant family gathered around a table under lamplight, sharing a meager meal of potatoes. Van Gogh intentionally used coarse features and dark colors to convey the manual labor and the connection these people had to the earth they worked. While he considered it a significant achievement, the painting was criticized for its dark palette and perceived clumsiness, foreshadowing the lack of appreciation he would face throughout his career.

During his time in The Hague (1881-1883), he received some formal instruction from his cousin-in-law, Anton Mauve, a leading painter of the Hague School. Mauve introduced him to watercolor and oil painting. However, their relationship soured, partly due to Vincent's difficult personality and his controversial relationship with Sien Hoornik, a former prostitute who became his model and companion. This period was marked by intense study but also personal turmoil and poverty.

Parisian Transformation: Embracing Color

In March 1886, Van Gogh moved to Paris to live with his brother Theo. This move proved to be a pivotal moment in his artistic development. Paris was the epicenter of the avant-garde art world, and Vincent was immediately exposed to the revolutionary styles of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. He encountered the work of artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, and Georges Seurat, whose vibrant colors and depictions of modern life stood in stark contrast to his earlier Dutch work.

He met many leading artists personally, including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard, and Paul Signac. He was particularly interested in the color theories being explored by the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists (like Seurat and Signac, who developed Pointillism). He began experimenting with a brighter palette, shorter brushstrokes, and complementary colors to create vibrant effects. His subject matter also shifted, incorporating Parisian cityscapes, portraits, still lifes, and self-portraits.

Another significant influence during his Paris years was Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints (Japonisme), which were highly fashionable at the time. Van Gogh became an avid collector and admirer of these prints, drawn to their bold outlines, flat areas of color, unconventional compositions, and depictions of nature. He copied several Japanese prints and incorporated their stylistic elements into his own work, evident in paintings like Portrait of Père Tanguy (1887), which features Japanese prints in the background. His two years in Paris fundamentally transformed his style, paving the way for the explosive creativity of his later periods.

The Arles Period: A Sun-Drenched Zenith

Seeking brighter light and color, and dreaming of establishing an artists' community, Van Gogh left the bustling environment of Paris in February 1888 and moved south to Arles in Provence. The period in Arles (February 1888 – May 1889) was intensely productive and marked the height of his artistic powers. Enchanted by the southern French landscape, the brilliant sunlight, and the vibrant colors, he worked with feverish energy, often outdoors.

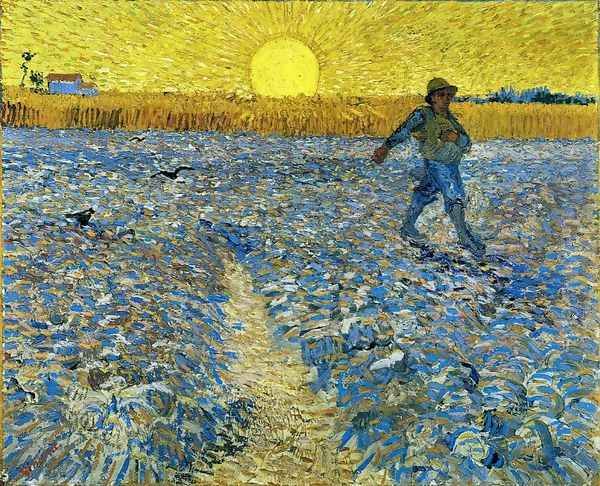

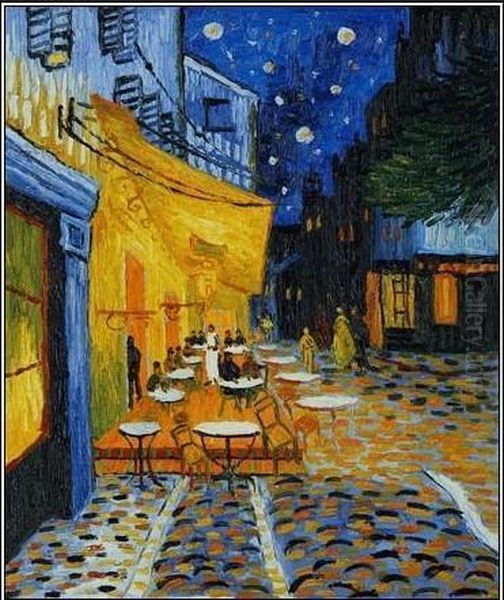

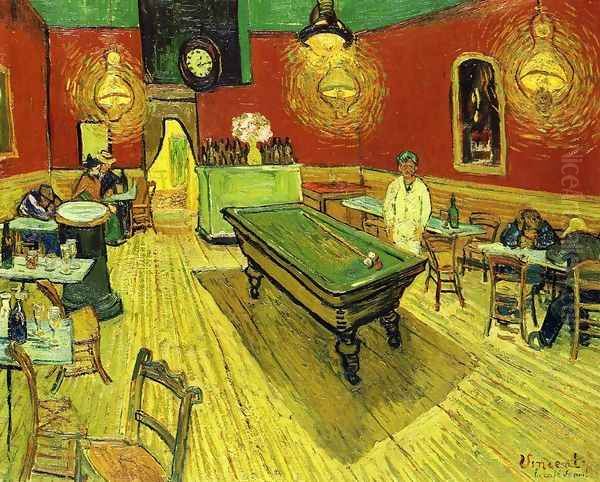

In Arles, his palette exploded with intense yellows, blues, and greens. His brushwork became even more expressive and dynamic, using thick applications of paint (impasto) to convey his emotional response to the world around him. He painted the Provençal landscape with its orchards in bloom, wheat fields under the sun, local townspeople, and scenes of daily life. Key works from this period include landscapes like The Sower (1888) and depictions of Arles such as Café Terrace at Night (1888) and The Night Café (1888).

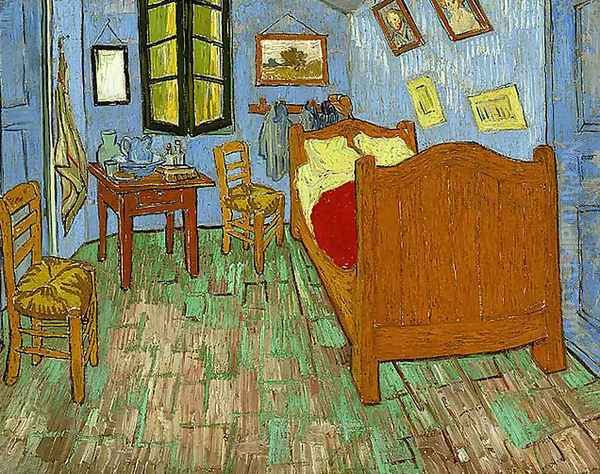

He rented the famous "Yellow House," hoping it would become the "Studio of the South," a haven where artists could live and work together. He decorated the house with paintings, most notably the iconic Sunflowers series (1888). These paintings, typically featuring sunflowers in a vase rendered in brilliant yellows, became symbols of his time in Arles and his connection to the sun and nature. He painted multiple versions, experimenting with different arrangements and shades of yellow, showcasing his mastery of color. Another significant work from this time is The Bedroom (1888), depicting his simple room in the Yellow House, using color and perspective to evoke a sense of rest and tranquility, though the tilted perspective also hints at underlying tension.

Collaboration and Conflict: The Gauguin Episode

Van Gogh's dream of an artists' colony partially materialized when Paul Gauguin, a fellow Post-Impressionist whom Vincent deeply admired, accepted his invitation (funded by Theo) to join him in Arles. Gauguin arrived in October 1888, and for nine weeks, the two artists lived and worked side-by-side in the Yellow House. This period saw intense artistic dialogue and mutual influence, but also growing friction.

Their temperaments and artistic approaches differed significantly. Van Gogh worked rapidly, often directly from nature, driven by intense emotion and using thick impasto. Gauguin, older and more established, worked more deliberately, often from memory or imagination, emphasizing synthesized forms and symbolic color ("Synthetism"). They debated art theory vigorously. While they learned from each other – Van Gogh experimented with painting from imagination, and Gauguin adopted some of Vincent's vibrant color – their relationship became increasingly strained.

The confined space of the Yellow House, combined with their strong personalities and differing views, led to frequent arguments. Gauguin found Vincent's volatile temperament difficult, while Vincent felt pressured by Gauguin's dominant personality and perhaps insecure about his own artistic standing. The collaboration, initially filled with hope, spiraled into conflict, culminating in a dramatic and tragic event.

The Ear Incident: A Descent into Crisis

The breaking point came on December 23, 1888. Following a particularly heated argument (the exact nature of which remains debated), Van Gogh suffered a severe mental breakdown. In a state of acute distress, he took a razor and cut off part, or possibly all, of his left ear. The exact sequence of events is unclear; Gauguin claimed Vincent threatened him with the razor first, prompting Gauguin to leave the house for the night.

After mutilating himself, Van Gogh wrapped the severed ear fragment in paper and delivered it to a woman named Rachel, who worked at a local brothel frequented by both artists. He then returned to the Yellow House and collapsed. He was found unconscious by police the next morning after Gauguin, returning to the house, raised the alarm. Gauguin promptly contacted Theo and left Arles, never to see Vincent again, though they did correspond later.

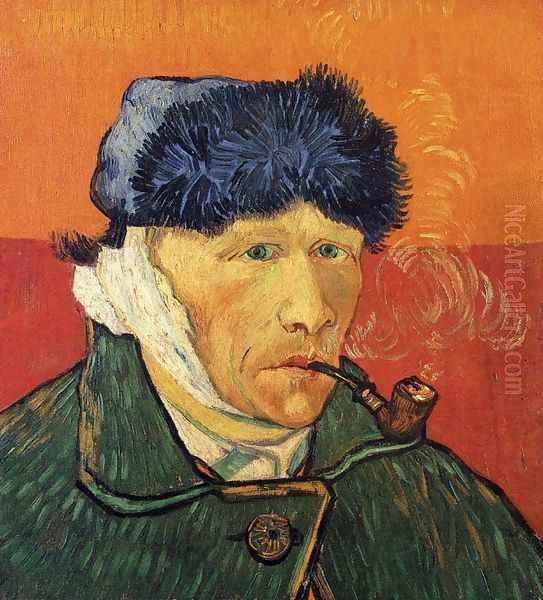

Van Gogh was admitted to the hospital in Arles, suffering from severe blood loss and acute psychosis. He had little memory of the event itself. This incident marked the beginning of a series of severe mental health crises that would plague him for the rest of his life. While recovering, he painted Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889), a stark and poignant depiction of his condition. The ear incident effectively ended his dream of the Studio of the South and signaled a darker phase in his life.

Saint-Rémy: Creativity Amidst Confinement

Following the ear incident and subsequent episodes of mental distress, including hallucinations and paranoia, Van Gogh voluntarily admitted himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in May 1889. He remained there for a year, confined for much of the time but allowed to paint when his condition permitted. Despite his recurring mental health struggles, this period was remarkably productive artistically.

Working within the asylum grounds or under supervision outside, Van Gogh continued to paint the surrounding landscape with undiminished intensity. His style evolved further, characterized by swirling, dynamic brushstrokes and often distorted forms that seemed to reflect his inner turmoil. He painted the asylum's garden, olive groves, cypress trees (which he saw as symbols of death and eternity), and the nearby Alpilles mountains.

It was during his confinement in Saint-Rémy that he painted one of his most famous and beloved works, Starry Night (1889). This iconic painting depicts the view from his asylum window just before sunrise, although it is largely a work of memory and imagination. The swirling, turbulent sky, the blazing stars and moon, the dark, flame-like cypress tree dominating the foreground, and the peaceful village below create a powerful image of cosmic energy and human longing. Other masterpieces from this period include Irises (1889) and numerous paintings of olive trees and wheat fields.

Auvers-sur-Oise: The Final Months

In May 1890, seeking to be closer to Theo in Paris and under the care of a physician sympathetic to artists, Van Gogh left the asylum in Saint-Rémy and moved to Auvers-sur-Oise, a village northwest of Paris. He was placed under the supervision of Dr. Paul Gachet, an amateur painter and homeopathic doctor who had treated other artists, including Camille Pissarro.

Initially, Van Gogh seemed calmer and threw himself into his work with extraordinary fervor. In just over two months in Auvers, he produced more than 70 paintings, an average of more than one a day. He painted the village, the surrounding wheat fields, portraits of Dr. Gachet and his daughter, and garden scenes. His style in Auvers often featured agitated brushwork and a sense of unease, even in seemingly tranquil subjects.

Works like Wheatfield with Crows (1890), with its turbulent sky, converging paths, and flock of dark crows, are often interpreted as expressions of his mounting despair and premonitions of death, although this interpretation is debated by art historians. Despite the intense productivity, his mental state remained fragile. He felt increasingly burdened by his dependence on Theo, who was facing his own financial and personal difficulties.

On July 27, 1890, Vincent van Gogh went out into the wheat fields he had been painting and shot himself in the chest with a revolver. He managed to stagger back to his room at the Auberge Ravoux. Theo rushed to his side, and Vincent died in his brother's arms two days later, on July 29, 1890, at the age of 37. His reported last words were, "The sadness will last forever." He was buried in the municipal cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise. Theo, devastated by Vincent's death, died just six months later and was eventually buried beside his brother.

Artistic Style: Brushstrokes of Emotion

Vincent van Gogh's artistic style is instantly recognizable and profoundly influential. As a Post-Impressionist, he built upon the Impressionists' use of color and light but pushed beyond their focus on capturing fleeting visual sensations. His primary aim was to express his intense emotional and spiritual responses to the world through powerful visual means.

Key characteristics of his style include:

Expressive Color: Van Gogh used color subjectively and symbolically, not just naturalistically. He employed vibrant, often unmixed colors and bold contrasts (like complementary colors placed side-by-side) to convey mood, emotion, and the intensity of his experience. His yellows in the Sunflowers or the deep blues and swirling yellows in Starry Night are prime examples. He admired the color theories of Eugène Delacroix.

Impasto and Dynamic Brushwork: He applied paint thickly (impasto), often directly from the tube, leaving visible, textured brushstrokes that follow the form of objects or create rhythmic patterns across the canvas. His brushstrokes are energetic, directional, and highly expressive – swirling, stabbing, or flowing – giving his paintings a sense of movement and vitality.

Emotional Intensity: Every element in his mature works seems charged with feeling. Landscapes, still lifes, and portraits are imbued with his personal struggles, joys, anxieties, and spiritual yearnings. His art is a direct conduit for his passionate inner life.

Influence of Japanese Prints: The bold outlines, flat planes of color, cropped compositions, and decorative qualities of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints had a lasting impact on his work, visible in his strong use of line and compositional choices.

Diverse Subject Matter: While known for landscapes and self-portraits, he tackled a wide range of subjects, including still lifes (flowers, shoes, books), portraits of ordinary people (postman Joseph Roulin, Dr. Gachet), and scenes of rural life. His numerous self-portraits offer a raw and unflinching chronicle of his psychological state.

Mental Health: The Shadow Over the Canvas

Vincent van Gogh's life was profoundly affected by severe mental health issues. While diagnosing historical figures retrospectively is complex, scholars and medical professionals, based on his letters, contemporary accounts, and medical records, have proposed various conditions. These include bipolar disorder (explaining his periods of intense energy and creativity alternating with deep depression), temporal lobe epilepsy (which can cause seizures, altered states of consciousness, and behavioral changes), borderline personality disorder, and possibly psychosis exacerbated by malnutrition, overwork, insomnia, and alcohol abuse (particularly absinthe).

He experienced recurrent episodes characterized by hallucinations (both auditory and visual), delusions, extreme anxiety, and incapacitating depression. These crises led to hospitalizations, including the famous ear incident and his year-long stay at the asylum in Saint-Rémy. His letters often describe his mental anguish, his fear of recurring attacks, and his struggle to maintain stability and continue working.

It is crucial, however, to avoid simplistic or romanticized notions linking his "madness" directly to his "genius." While his emotional intensity undoubtedly fueled his art, his most significant works were generally created during periods of relative lucidity and control between debilitating attacks. His illness caused immense suffering and ultimately contributed to his tragic death, but his art was the product of conscious effort, skill, and profound artistic vision, not merely a byproduct of mental instability.

Financial Struggles and Theo's Support

Throughout his artistic career, Vincent van Gogh lived in poverty and was almost entirely dependent on the financial support of his brother Theo. Despite producing nearly 900 oil paintings and over 1,100 drawings and sketches in just a decade, he achieved virtually no commercial success during his lifetime. Art supplies were expensive, and the stipends from Theo often barely covered his basic living expenses and materials.

The only painting confirmed to have been sold during his lifetime was The Red Vineyard (1888), purchased for 400 francs by Anna Boch, an Impressionist painter and collector, at the Les XX exhibition in Brussels in 1890. This lack of recognition and financial independence was a source of great anxiety and guilt for Vincent, who felt like a burden on his brother.

Theo van Gogh's role cannot be overstated. As an art dealer in Paris, he not only provided the funds that allowed Vincent to paint but also supplied him with materials, offered critical feedback, kept him informed about the art world, and tirelessly championed his work. Theo believed deeply in Vincent's talent, even when few others did. Their relationship, documented in their letters, was one of deep affection, mutual dependence, and occasional strain, but it was the bedrock upon which Vincent's artistic career was built.

Legacy and Influence: A Posthumous Triumph

Vincent van Gogh's fame is almost entirely posthumous. Following his death, Theo intended to promote his brother's work but died himself only six months later. It was Theo's widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, who dedicated herself to preserving Vincent's legacy. She carefully managed his vast collection of paintings and drawings, organized exhibitions, and published his letters to Theo, gradually bringing his work to public attention.

Major exhibitions in Paris, Amsterdam, and other European cities in the early 20th century cemented Van Gogh's reputation. His expressive use of color and form had a profound impact on subsequent generations of artists. The Fauves, including Henri Matisse and André Derain, were inspired by his bold, non-naturalistic color. The German Expressionists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Edvard Munch, admired his emotional intensity and psychological depth. His influence can also be seen in the work of Abstract Expressionists and countless other modern and contemporary artists.

Today, Vincent van Gogh is celebrated as one of the giants of art history. His paintings are among the most recognizable and valuable in the world, housed in major museums and fetching record prices at auction. His life story, marked by passion, suffering, and artistic devotion, has captured the popular imagination, inspiring numerous books, films, and songs. He remains a symbol of the misunderstood genius, the artist whose vision transcended the limitations of his time.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh's journey was one of relentless searching – for purpose, for connection, for spiritual truth, and for a visual language capable of expressing the turbulent beauty he perceived in the world and felt within himself. In a remarkably short and often tormented artistic career spanning only a decade, he produced a body of work that fundamentally altered the course of modern art. His canvases pulse with life, color, and raw emotion, offering an intimate glimpse into the soul of a man who painted not just what he saw, but what he felt.

From the dark, earthy tones of his early Dutch works to the incandescent brilliance of his paintings from Arles and Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh's art charts a path of radical innovation and profound personal expression. Though unrecognized and impoverished during his life, his passionate brushstrokes left an indelible mark on the world. His legacy endures not only in the museums and galleries that showcase his masterpieces but also in the hearts of millions who continue to be moved by the power, honesty, and sheer humanity of his art. Vincent van Gogh's sadness may have lasted his lifetime, but the vibrant joy and poignant beauty he captured on canvas continue to resonate forever.