Domenico Gargiulo, known to his contemporaries and to posterity as Micco Spadaro, stands as a pivotal figure in the vibrant artistic milieu of 17th-century Naples. Born around 1609-1610 and active until his death in approximately 1675, Gargiulo's life and work are inextricably linked with the tumultuous history and unique cultural fabric of this southern Italian metropolis. His canvases serve not only as artistic achievements of the Baroque period but also as invaluable historical documents, capturing the city's triumphs, disasters, and the daily life of its people with a keen and often unflinching eye.

His moniker, "Micco Spadaro," translates to "Little Sword-Maker," a direct reference to his father's profession as a swordsmith. This nickname, affectionate and descriptive, rooted him firmly in the artisan class of Naples, a background that perhaps informed his empathetic portrayal of common folk and dramatic street scenes, setting him apart from artists who focused solely on aristocratic or purely devotional commissions.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in a Bustling Metropolis

Naples in the early 17th century was one of Europe's largest and most densely populated cities, a Spanish viceroyalty teeming with life, stark social contrasts, and a fervent religious atmosphere. It was a crucible of artistic innovation, profoundly impacted by the revolutionary realism of Caravaggio, who had worked there briefly but left an indelible mark. This environment provided a fertile ground for young talents like Gargiulo.

His artistic journey began in the esteemed workshop of Aniello Falcone, a painter renowned for his dynamic battle scenes. Falcone's tutelage undoubtedly honed Gargiulo's skills in composing complex, multi-figure compositions and capturing movement and drama. This training would prove essential for Gargiulo's later depictions of crowded public events and chaotic historical moments.

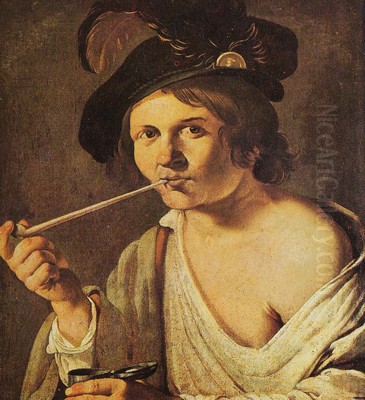

Gargiulo is also documented as having studied alongside Salvator Rosa, another significant Neapolitan Baroque artist, under Falcone. Rosa, known for his wild, romantic landscapes, philosophical subjects, and rebellious spirit, likely shared an intellectual and artistic camaraderie with Gargiulo. While their paths diverged stylistically, the shared formative experience under Falcone and the vibrant Neapolitan artistic scene would have fostered a rich exchange of ideas. Early influences on Gargiulo's developing style also included the works of landscape specialists like the Flemish painter Paul Bril, active in Rome, and Filippo Napoletano (born Filippo d'Angeli), whose small-scale landscapes and genre scenes were popular.

The Neapolitan Crucible: A City of Contrasts

To understand Gargiulo's art, one must appreciate the character of 17th-century Naples. It was a city of breathtaking beauty, set against the stunning backdrop of the Bay of Naples and the ever-present, ominous silhouette of Mount Vesuvius. Yet, it was also a city of extreme poverty, social unrest, and vulnerability to natural disasters and disease. Spanish rule, while bringing a certain grandeur, also led to heavy taxation and periodic revolts.

This potent mix of splendor and squalor, piety and rebellion, became the raw material for Gargiulo's brush. He was less interested in the idealized visions of classical mythology or the serene depictions of saints favored by some contemporaries, and more drawn to the raw, unfiltered reality of his city. His work often focused on the urban peripheries, the bustling markets, the crowded piazzas, and the dramatic events that shaped Neapolitan life. This focus aligns him somewhat with the Bamboccianti painters active in Rome, such as Pieter van Laer, who specialized in scenes of everyday Roman life, often featuring peasants and artisans.

Artistic Style: A Fusion of Realism and Baroque Drama

Gargiulo's style is a compelling synthesis of naturalistic observation and Baroque theatricality. He possessed a remarkable ability to render detailed, almost journalistic accounts of events, populating his canvases with a multitude of small, animated figures, each contributing to the overall narrative. His palette could range from somber tones, appropriate for scenes of plague or destruction, to brighter, more vibrant colors in depictions of festivals or biblical celebrations.

The influence of Caravaggio's realism, filtered through the Neapolitan school, is evident in the tangible quality of his figures and settings. However, Gargiulo's compositions often embrace the dynamism and dramatic lighting characteristic of the High Baroque. He was a master storyteller, arranging his figures and architectural elements to guide the viewer's eye and convey the emotional intensity of the scene. His landscapes, while often serving as backdrops to human activity, are rendered with a sensitivity to atmosphere and local color.

A key aspect of his work is the depiction of crowds. Whether it's a marketplace, a procession, or a scene of panic, Gargiulo excelled at orchestrating large numbers of figures, creating a sense of bustling energy or collective despair. This skill was undoubtedly honed under Falcone but developed into a signature element of his own unique vision. He also frequently collaborated with other artists, most notably Viviano Codazzi.

Chronicler of Calamity and Upheaval

Domenico Gargiulo's most enduring legacy lies in his powerful visual records of the major historical events that shook Naples during his lifetime. These paintings are more than mere illustrations; they are immersive experiences that convey the human drama of these moments.

The Eruption of Vesuvius (1631)

The catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in December 1631 was a terrifying event that devastated the surrounding region and sent shockwaves of fear through Naples. Gargiulo, then a young artist, produced several depictions of this disaster. His paintings, such as The Eruption of Vesuvius, capture the apocalyptic scale of the event: the fiery mountain spewing ash and lava, the darkened sky, and the desperate flight of the populace. Processions of penitents, carrying religious icons and praying for divine intervention, are often prominent, reflecting the deep religiosity of the Neapolitan people in times of crisis. These works are invaluable for their topographical accuracy as well as their emotional power, showing the city under a pall of smoke and ash.

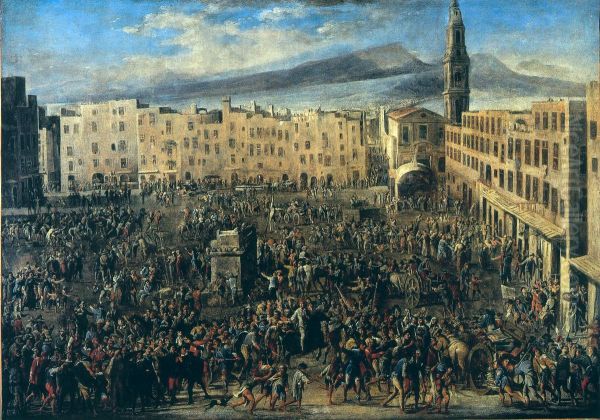

The Revolt of Masaniello (1647)

In 1647, Naples erupted in a popular revolt against Spanish rule, sparked by a new tax on fruit. The uprising was led by a young fisherman named Tommaso Aniello, known as Masaniello. For a brief, tumultuous period, Masaniello held sway over the city. Gargiulo documented this dramatic episode in paintings like The Revolt of Masaniello and The Execution of the Nobles during the Revolt of Masaniello. These works are characterized by their crowded, chaotic scenes, depicting the fervor of the rebels, the violence in the streets, and the eventual suppression of the revolt. Gargiulo's canvases provide a vivid glimpse into the social tensions and political instability of Spanish Naples, capturing the raw energy of popular uprising and the brutal realities of its consequences. The Piazza del Mercato, a central hub of the revolt, features prominently in these depictions.

The Plague of Naples (1656)

Perhaps Gargiulo's most harrowing and famous works are those depicting the devastating plague that ravaged Naples in 1656, wiping out a significant portion of its population. His painting Market Square, the Plague of Naples (also known as Largo Mercatello during the Plague of 1656 or Piazza Mercatello, Naples, during the Plague of 1656), now in the Museo Nazionale di San Martino, is a chilling masterpiece. It portrays the Largo di Mercatello, one of the city's main squares, transformed into an open-air charnel house. The canvas is filled with haunting details: bodies being carted away, grieving survivors, overwhelmed caregivers, and the eerie emptiness of a city gripped by death. Gargiulo does not shy away from the grim reality of the epidemic, yet his depiction is imbued with a sense of human tragedy rather than gratuitous horror. The presence of religious figures and symbols underscores the search for solace and meaning amidst overwhelming suffering. This work, along with others on the same theme, solidifies his reputation as a visual historian of his city's darkest hours. The stark realism echoes the dramatic intensity found in the works of Jusepe de Ribera, another towering figure of Neapolitan Baroque, known for his unflinching portrayals of martyrdom and human suffering.

Religious, Mythological, and Genre Scenes

While renowned for his historical chronicles, Gargiulo also produced a significant body of work encompassing religious subjects, mythological scenes, and genre paintings. His religious paintings often featured Old and New Testament stories, rendered with the same attention to narrative detail and human emotion found in his historical works.

One notable example is The Israelites Celebrating David's Return, a vibrant composition filled with numerous figures in a festive procession. Such works allowed Gargiulo to explore different moods and settings, showcasing his versatility. He also painted scenes like The Massacre of the Innocents, a subject that lent itself to dramatic, multi-figure compositions, echoing the chaos of his historical paintings but within a biblical context.

His genre scenes, often depicting everyday life in Naples, further highlight his interest in the activities of ordinary people. These might include market scenes (when not overshadowed by plague), street performances, or rustic gatherings. These works provide a valuable counterpoint to the grand religious and historical narratives, offering a more intimate look at 17th-century Neapolitan society.

Collaborations and Workshop

Collaboration was common practice in 17th-century artistic workshops, and Gargiulo was no exception. His most significant and frequent collaborator was Viviano Codazzi, a specialist in architectural perspective paintings, known as vedute. Codazzi would typically paint the architectural settings – classical ruins, grand colonnades, or cityscapes – while Gargiulo would populate these scenes with his characteristic small, lively figures. This partnership resulted in numerous successful paintings, combining Codazzi's mastery of perspective and architectural detail with Gargiulo's skill in narrative figuration. Their joint works often depicted biblical scenes, historical events, or imaginary architectural capriccios.

Gargiulo also collaborated with the Flemish painter Hendrick de Somer (known in Italy as Enrico Fiammingo), particularly in the 1640s. In these collaborations, De Somer, known for his robust, Caravaggesque figures, would often paint the principal characters, while Gargiulo would contribute the landscape or background elements and smaller figures.

Like many successful artists of his time, Gargiulo maintained a workshop and had pupils who learned his style and assisted in commissions. Among his documented students were Pietro Pesca (or Pesce) and Ignazio Santoro (or Galli). Through his workshop, Gargiulo's influence extended to the next generation of Neapolitan painters.

Major Commissions and Later Career

Throughout his career, Gargiulo received commissions for both private collectors and public institutions, including churches. He contributed to the decoration of important religious sites in Naples, such as the church of Santa Maria la Nova and the Certosa di San Martino. The Certosa, a vast Carthusian monastery complex overlooking the city, was a major center of artistic patronage, and Gargiulo's work there included frescoes depicting scenes from the Old Testament and the lives of Carthusian saints. These large-scale projects demonstrated his ability to work in different media and adapt his style to the demands of monumental decoration.

His frescoes in the choir of Santa Maria da Sapienza, depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin, further attest to his standing as a respected religious painter. These commissions placed him in the company of other leading Neapolitan artists of the period, such as Massimo Stanzione, Bernardo Cavallino, and later, Mattia Preti and Luca Giordano, all of whom contributed to Naples' rich artistic tapestry.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Domenico Gargiulo, or Micco Spadaro, occupies a unique and important place in the history of Italian Baroque art. His primary significance lies in his role as a visual chronicler of 17th-century Naples. His paintings of the Vesuvius eruption, Masaniello's revolt, and the plague are unparalleled in their immediacy and historical value. They offer a window into the experiences of a city repeatedly tested by disaster and social upheaval.

Beyond their documentary importance, Gargiulo's works are artistically significant for their lively narrative style, their skillful handling of complex crowd scenes, and their empathetic portrayal of human drama. He successfully blended the lessons of Neapolitan realism, particularly the legacy of Caravaggio and Ribera, with the dynamic compositional principles of the Baroque. His focus on the everyday life and the dramatic historical events of his city, rather than exclusively on idealized or mythological subjects, distinguishes him from many of his contemporaries.

His collaborations, particularly with Viviano Codazzi, produced a distinctive body of work that combined strengths in figure painting and architectural perspective. His influence can be seen in the work of his pupils and in the broader tradition of Neapolitan genre and historical painting.

Today, Gargiulo's paintings are held in major museums and collections worldwide, including the Museo Nazionale di San Martino and the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and many others. They continue to be studied by art historians not only for their artistic merit but also for the rich historical and cultural insights they provide into one of Europe's most fascinating cities during a pivotal century. His ability to capture the specific character of Naples, its vibrancy, its suffering, and its resilience, ensures his enduring relevance. He was, in essence, the city's visual biographer, a painter whose brushstrokes narrated the epic and the everyday life of Baroque Naples for generations to come. His work stands as a testament to the power of art to record, interpret, and preserve the human experience in all its complexity.