Domenico Piola stands as one of the most significant and prolific artists of the Italian Baroque period, particularly dominating the artistic scene in Genoa during the latter half of the 17th century. Born into a city renowned for its wealth, maritime power, and splendid palaces, Piola became the leading figure in decorating these magnificent spaces, leaving an indelible mark on the visual culture of the Republic of Genoa. His long and productive career, spanning from the mid-17th century until his death in 1703, saw the creation of countless frescoes, oil paintings, drawings, and designs, establishing his workshop, the "Casa Piola," as the preeminent artistic enterprise in the region.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Domenico Piola was born in Genoa, likely in 1627 or 1628. He hailed from a family involved in textiles, but his elder brother, Pellegrino Piola, was already establishing himself as a talented painter. Domenico's artistic journey began under Pellegrino's guidance. However, tragedy struck in 1640 when Pellegrino was unexpectedly killed, a victim of violence. This event profoundly impacted the young Domenico, who was then only in his early teens.

Following his brother's death, Domenico Piola is believed to have inherited the studio space. He continued his artistic education, formally training with Giovanni Domenico Cappellino, a competent painter but perhaps less innovative than Domenico's innate talent would eventually prove. Cappellino provided a solid foundation, but Piola's artistic vision would soon be shaped by more dynamic contemporary forces within the vibrant Genoese art world.

Genoa at this time was a crucible of artistic exchange. While influenced by Roman and Bolognese developments, it fostered its own distinct artistic identity. Piola quickly absorbed the prevailing trends, moving beyond the somewhat conservative style of his initial training.

Key Influences and Stylistic Evolution

Piola's artistic development was significantly shaped by two dominant figures in the Genoese school: Valerio Castello and Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, known as Il Grechetto. His association and collaboration with Valerio Castello, particularly from the late 1640s until Castello's premature death in 1659, was crucial. Castello's style was characterized by fluid brushwork, dynamic compositions, and a light, airy palette, representing a Genoese interpretation of the High Baroque. Working alongside Castello on major decorative projects pushed Piola towards a more energetic and expressive manner.

Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, famed for his pastoral scenes, innovative printmaking techniques, and rich, textured paint application, also left a mark on Piola. While their styles differed, Castiglione's influence might be seen in Piola's handling of certain themes, his complex allegories, and perhaps aspects of his drawing technique. Piola, like Castiglione, became a master draftsman, producing numerous preparatory sketches.

Furthermore, echoes of earlier masters can be discerned. Some scholars note the influence of Parmigianino's elegant Mannerism in the elongated grace of certain figures, suggesting Piola studied and absorbed lessons from the High Renaissance and Mannerist periods alongside the prevailing Baroque trends. He synthesized these influences into a distinctive personal style.

Piola's mature style is quintessentially Baroque. It features dramatic compositions, often employing diagonal recessions and swirling vortexes of figures, especially in his ceiling frescoes designed to be viewed from below (sotto in sù). He utilized a rich, often warm color palette and employed strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to heighten the emotional impact and three-dimensionality of his scenes. His figures are typically robust and dynamic, conveying a sense of energy and movement.

A particular hallmark of Piola's work is his delightful rendering of putti, or cherubs. These playful, chubby infants populate his religious and mythological scenes, adding a sense of lightness and charm. His ability to capture their innocent exuberance became widely recognized and imitated. He demonstrated great versatility, adeptly handling grand religious narratives, complex mythological allegories, and more intimate devotional subjects.

The Casa Piola: A Dominant Artistic Workshop

Domenico Piola was not merely an individual artist; he was the head of a large, highly organized, and immensely successful family workshop known as "Casa Piola." This studio became the dominant force in Genoese painting and decoration for several decades, securing the most prestigious commissions from the city's patrician families and religious orders. Located in the heart of Genoa, it functioned as a hub of artistic production.

The workshop's success was built on a collaborative family model. Domenico worked alongside his brothers, initially Pellegrino and later possibly Giovanni Andrea Piola. More significantly, he trained and employed his own sons: Paolo Gerolamo Piola, who would become his primary successor, Antonio Maria Piola, and Giovanni Battista Piola. His talented son-in-law, Gregorio de Ferrari, also trained in the workshop and became a key collaborator before developing his own distinct, slightly later Baroque style.

Casa Piola operated efficiently, capable of undertaking vast decorative projects. This often involved a division of labor common in large Baroque workshops. Domenico might design the overall composition and paint the principal figures, while assistants and collaborators handled secondary elements, architectural frameworks (quadratura), or decorative details. The workshop produced not only frescoes and large-scale canvases but also smaller paintings, numerous drawings, designs for prints, book illustrations, and even potentially for decorative arts like furniture or ephemeral decorations for festivals.

The sheer volume of work attributed to Piola and his workshop attests to their efficiency and the high demand for their services among Genoa's elite, including powerful families like the Spinola, Doria, Balbi, and Lomellini, who adorned their city palaces and country villas with elaborate decorative schemes.

Master of Fresco: Adorning Genoa's Palaces and Churches

Domenico Piola's most enduring fame rests on his extensive work as a fresco painter. The magnificent palaces of Genoa's aristocracy, the Palazzi dei Rolli (many now UNESCO World Heritage sites), and the city's richly decorated churches provided ample canvases for his talents. He became the go-to artist for the large-scale ceiling and wall decorations that characterized Genoese Baroque interiors.

His contributions to sacred spaces were significant. In the church of San Luca, belonging to the Spinola family, he painted the impressive Coronation of the Virgin in the apse vault, a celestial vision filled with light and movement. For the church of Santa Marta, he executed frescoes including a notable Birth of the Virgin, showcasing his narrative skill and warm palette. He also contributed works to other major churches, potentially including San Siro and Santissima Annunziata del Vastato, often working alongside other artists and stuccoists.

Piola's work equally defined the secular splendor of Genoese palaces. In the Palazzo Rosso, he decorated several rooms with mythological and allegorical frescoes, such as the Sala della Primavera (Spring Room) and Sala dell'Estate (Summer Room), integrating his painted scenes seamlessly with elaborate stucco surrounds. He also worked in the nearby Palazzo Bianco.

A particularly celebrated example of his palace decoration is the ceiling fresco Allegory of Peace (c. 1673) in the Palazzo Spinola di Pellicceria (now the Galleria Nazionale della Liguria). This complex work features mythological figures like Janus (god of beginnings and endings, closing the doors of war), Diana (goddess of the hunt), Bacchus (god of wine), and Ceres (goddess of agriculture), likely celebrating peace and prosperity, perhaps linked to a specific historical event or the Spinola family's fortunes. The composition skillfully draws the viewer's eye upwards into an illusionistic sky.

These fresco cycles demonstrate Piola's mastery of complex compositions, his ability to manage large surfaces, his understanding of perspective and foreshortening (sotto in sù), and his skill in creating vibrant, immersive environments that proclaimed the wealth and sophistication of his patrons.

Versatility: Oil Paintings, Drawings, and Designs

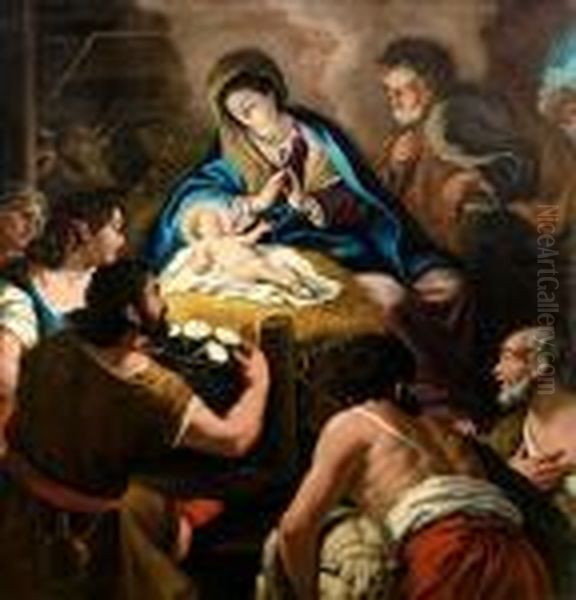

While renowned for frescoes, Domenico Piola was also a highly accomplished painter in oils. He produced numerous altarpieces for churches throughout Liguria, often depicting dramatic moments from the lives of saints or key biblical events. Examples include works like the Assumption of the Virgin and the Miracle of St. Peter, showcasing his ability to convey intense religious feeling.

He also painted mythological and allegorical subjects on canvas for private collectors. The Triumph of Bacchus, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, exemplifies his dynamic approach to classical themes, filled with revelry and movement. Other notable oil paintings include The Flight into Egypt, demonstrating a more tender and narrative quality, and historical subjects like The Family of Darius before Alexander the Great, showcasing his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with psychological nuance. Numerous versions of the Madonna and Child also came from his workshop, catering to devotional needs.

Piola's activity as a draftsman was fundamental to his practice and incredibly prolific. Thousands of his drawings survive today, housed in collections worldwide. These drawings reveal his working process, from rapid initial ideas (primi pensieri) jotted down with energetic pen lines, to more detailed studies of figures and drapery, often using chalk or wash to explore light and shadow. He also created highly finished presentation drawings (modelli) in pen, ink, and wash, intended to show patrons the final design for approval before work began on a large-scale fresco or altarpiece. These drawings are not just preparatory works; they are often vibrant works of art in their own right, showcasing his fluid line and compositional inventiveness.

Beyond painting and drawing, Piola engaged with printmaking, sometimes providing designs for engravers, which helped disseminate his compositions more widely. His designs were also used for book illustrations, contributing to the visual culture of Genoese publishing. This multifaceted output underscores the central role he and his workshop played in the artistic life of the city.

Notable Collaborations

The collaborative nature of Baroque workshops was essential to their productivity, and Casa Piola was no exception. Domenico Piola's career is marked by significant partnerships with other artists, blending skills to create unified decorative ensembles.

His early collaboration with Valerio Castello was formative, as previously mentioned. They worked together on several major projects, likely influencing each other's styles during the 1650s. Their combined efforts helped define the exuberant character of mid-century Genoese Baroque decoration.

A crucial long-term collaborator was his son-in-law, Gregorio de Ferrari. Initially Piola's student, De Ferrari married Piola's daughter Margherita and became a leading painter in his own right. While developing a distinct style often seen as prefiguring the Rococo with its lighter palette and more sinuous lines, he frequently worked alongside Piola on large commissions, particularly in palace decorations. Their joint projects represent a fusion of two generations of Genoese Baroque mastery.

Piola also collaborated with specialists. Stefano Camogli, a painter known for his skill in depicting still life elements like flowers, fruit, and animals, sometimes worked with Piola. In such collaborations, Piola would typically paint the figures, while Camogli would add the detailed settings or still-life components, creating richly textured compositions.

He is also documented as having connections or collaborations with Domenico Fiasella, known as "Il Sarzana," an older and respected master of the Genoese school. This interaction highlights the interconnectedness of the artistic community in Genoa, where artists with established reputations might still join forces on particularly large or prestigious undertakings.

Later Career and Enduring Legacy

Domenico Piola remained active and highly sought after throughout his long life. His career, however, was not without challenges. A significant event was the devastating French naval bombardment of Genoa in 1684. This act of aggression caused widespread destruction in the city. Piola's own residence and studio were reportedly damaged or destroyed, and work he was undertaking at the church of San Leonardo was interrupted.

Despite this setback, Piola demonstrated resilience, continuing his artistic production. He and his workshop carried on securing major commissions, adapting perhaps to the changing needs and tastes of the post-bombardment city, which saw significant rebuilding and redecoration efforts.

As Piola aged, his son Paolo Gerolamo Piola increasingly took on a leading role in the workshop. Paolo Gerolamo had spent time in Rome, where he absorbed the more classicizing trends associated with artists like Carlo Maratta. Upon his return to Genoa, he brought these influences into the Casa Piola style, leading to a subtle shift in the workshop's output in its later years, blending Piola's established Baroque dynamism with a greater sense of classical order and clarity.

Domenico Piola died in Genoa in 1703, leaving behind an immense body of work and a securely established artistic dynasty. His influence on Genoese art was profound and lasting. For nearly half a century, he had been the city's preeminent painter, defining the visual language of its sacred and secular spaces. His style was widely imitated, and the Casa Piola continued to be active under his sons, ensuring the family's artistic impact extended into the early 18th century.

His legacy is preserved not only in the numerous frescoes and paintings that still adorn Genoa's buildings but also in the vast corpus of drawings that attest to his creative process and draftsmanship. He remains a central figure for understanding the unique character of the Genoese Baroque – an art of exuberant energy, rich color, and dramatic flair, perfectly suited to the proud maritime republic he called home.

Conclusion

Domenico Piola was more than just a painter; he was an artistic institution in 17th-century Genoa. As the driving force behind the Casa Piola workshop, he oversaw an unparalleled output of frescoes, oil paintings, drawings, and designs that shaped the aesthetic of the city. Influenced by masters like Valerio Castello and Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, he forged a powerful and dynamic Baroque style characterized by vibrant color, dramatic light, and energetic figures, particularly his signature putti. His collaborations, especially with family members like Gregorio de Ferrari and Paolo Gerolamo Piola, ensured the workshop's dominance and longevity. Despite personal and civic challenges, such as the French bombardment of 1684, Piola's productivity and influence remained undimmed. He stands today as the quintessential master of the Genoese Baroque, whose works continue to impress viewers with their technical brilliance and expressive power.