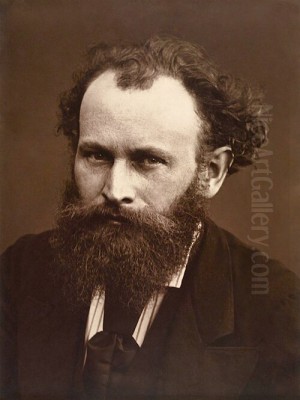

Édouard Manet stands as one of the most influential and controversial figures in the history of Western art. Born in Paris on January 23, 1832, into an era of artistic upheaval and societal change, Manet became a crucial link between the traditions of Realism and the burgeoning movement of Impressionism. Though he resisted easy categorization and famously refused to exhibit with the Impressionists, his work fundamentally challenged the artistic conventions of his time and paved the way for modern art. His life and career were marked by scandal, innovation, and an unwavering commitment to depicting the realities of contemporary life. He passed away in Paris on April 30, 1883, leaving behind a legacy that continues to provoke and inspire.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Manet hailed from a privileged background. His father, Auguste Manet, was a high-ranking official in the Ministry of Justice, and his mother, Eugénie-Désirée Fournier, was the goddaughter of the Swedish Crown Prince Charles Bernadotte. His family envisioned a respectable career in law for Édouard, a path he staunchly resisted. Instead, driven by an early passion for art, encouraged by his maternal uncle Edmond Fournier, he sought alternative routes.

At the age of sixteen, in a bid to appease his father while avoiding law, Manet attempted to join the Navy. He sailed to Rio de Janeiro on a training vessel, but his experiences at sea did little to sway him from his artistic calling. Crucially, he failed the entrance examination for the Navy twice. Faced with their son's determination and lack of aptitude for a naval career, his parents finally relented and allowed him to pursue art.

In 1850, Manet entered the studio of the acclaimed academic painter Thomas Couture. Couture was known for his large-scale historical paintings, such as the immensely popular "Romans of the Decadence." While Manet spent six years under Couture's tutelage, learning traditional techniques and the importance of draftsmanship, their relationship was often contentious. Manet found Couture's methods restrictive and his emphasis on historical subjects outdated, already feeling the pull towards contemporary themes. He frequently clashed with his master, yet this period provided him with a solid technical foundation. Alongside his studio work, Manet diligently copied the Old Masters at the Louvre, particularly drawn to the works of Spanish and Dutch painters.

Travels and Formative Influences

Manet's artistic education extended far beyond Couture's studio and the Louvre. Extensive travels throughout Europe were crucial in shaping his unique vision. He visited Italy, absorbing the lessons of Renaissance masters like Titian and Raphael, whose compositions he would later reference and subvert. Trips to the Netherlands exposed him to the vigorous brushwork and psychological depth of painters like Frans Hals and Rembrandt. Germany also featured on his itinerary.

However, it was his encounters with Spanish art that proved most transformative. Manet developed a profound admiration for the Spanish Golden Age painter Diego Velázquez, whom he called "the painter of painters." He lauded Velázquez's realism, his sophisticated use of black and grey tones, and his direct, unidealized portrayal of subjects. The influence of Francisco Goya was equally significant; Manet responded to Goya's bold technique, his unflinching depiction of modern life's darker aspects, and his powerful social commentary, evident in works like "The Third of May 1808." This Spanish influence would manifest clearly in Manet's early works through his dramatic use of light and shadow, a preference for flattened space, and bold outlines.

Another critical, non-Western influence emerged in the form of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, which were becoming increasingly popular in Paris during the mid-19th century. Manet, like many of his contemporaries including James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Edgar Degas, was captivated by their asymmetrical compositions, flat planes of color, unconventional cropping, and emphasis on decorative patterns. These elements would subtly permeate his work, contributing to his departure from traditional Western perspective and modeling.

Challenging the Salon: Early Works and Controversies

The official Paris Salon, the annual exhibition sponsored by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage in 19th-century France. Acceptance was crucial for an artist's career, but the jury notoriously favored conservative, academic styles. Manet's relationship with the Salon would be fraught with conflict from the outset.

His first submission in 1859, "The Absinthe Drinker" (Le Buveur d'absinthe), was rejected. The painting depicted a lone, down-and-out figure in a top hat leaning against a wall, a bottle resting at his feet. Its stark realism, dark palette reminiscent of Spanish masters, and focus on a subject from the margins of society were deemed crude and inappropriate by the jury. Only the intervention of Eugène Delacroix, a respected Romantic painter on the jury, saved it from unanimous rejection. This initial setback was a significant blow but also solidified Manet's resolve to paint modern life as he saw it.

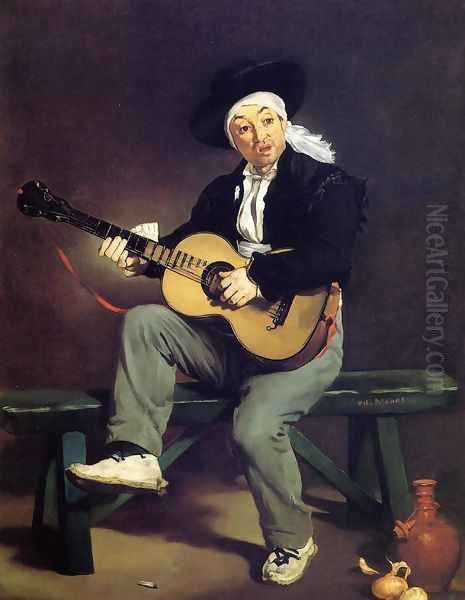

He achieved his first Salon success in 1861 with "The Spanish Singer" (Le Chanteur espagnol), a work capitalizing on the Parisian vogue for Spanish themes. Its lively brushwork and exotic subject matter earned praise from critics like Théophile Gautier. He also exhibited a portrait of his parents (Portrait de M. et Mme. Manet) that year, showcasing his skill in a more traditional genre, though even this relatively conventional work drew some criticism for its perceived lack of finish.

The turning point came in 1863. Manet submitted three paintings to the Salon, including the work now known as "Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe" (The Luncheon on the Grass). That year, the Salon jury rejected an unprecedented number of works, leading to widespread protest from artists. Emperor Napoleon III, in a conciliatory gesture, established the "Salon des Refusés" (Salon of the Rejected) to allow the public to judge the rejected works for themselves. Manet chose to exhibit "Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe" there, and it became the succès de scandale of the exhibition.

"Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe" depicted two fully clothed modern gentlemen picnicking in a woodland setting alongside a completely nude woman, who gazes directly and disconcertingly at the viewer. Another partially dressed woman bathes in the background. While the composition referenced Renaissance works (specifically Titian/Giorgione's "Pastoral Concert" and an engraving after Raphael's "Judgment of Paris"), its contemporary setting, the juxtaposition of the nude female with clothed bourgeois men, and Manet's bold, flattened style, which eschewed traditional modeling and perspective, shocked audiences. Critics condemned it as immoral, vulgar, and technically incompetent. Yet, it announced Manet as a radical innovator, unafraid to tackle modern subjects in a modern style.

Olympia: The Scandal Perfected

If "Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe" caused a stir at the Salon des Refusés, Manet's "Olympia," exhibited at the official Salon of 1865, provoked an even greater firestorm. This painting depicted a nude woman reclining on a bed, attended by a black servant presenting her with a bouquet of flowers, while a black cat stands alert at the foot of the bed. Like "Le Déjeuner," "Olympia" clearly referenced a Renaissance masterpiece, Titian's "Venus of Urbino." However, Manet stripped the mythological pretext away.

Olympia was no goddess or idealized nude; she was widely recognized by contemporary viewers as a modern Parisian prostitute. Her gaze is not coy or inviting but startlingly direct, confrontational, and appraising. She appears self-possessed and unashamed. The harsh, almost flat lighting eliminates soft shadows and emphasizes the contours of her body, further distancing the work from academic ideals of beauty. The inclusion of the black servant and the black cat added layers of commentary on race, class, and sexuality that were deeply unsettling to the bourgeois audience.

The public reaction was vitriolic. Critics lambasted the painting for its perceived ugliness, immorality, and technical crudeness ("unfinished" appearance). The outcry was so intense that the painting had to be hung high on the wall, guarded by attendants, to protect it from physical attack. Despite, or perhaps because of, the scandal, "Olympia" cemented Manet's reputation as the leader of the avant-garde. It embodied the poet Charles Baudelaire's call for an art that captured the "heroism of modern life," confronting viewers with the often-unacknowledged realities of contemporary Paris. The writer Émile Zola became one of Manet's staunchest defenders, praising his honesty and modern vision.

Manet and the Impressionists: A Complex Relationship

Manet is often called the "Father of Impressionism," yet his connection to the movement was complex and ambivalent. He was undoubtedly a pivotal influence and a central figure in the circle of artists who would form the Impressionist group, but he consistently refused to participate in their independent exhibitions, preferring to seek recognition within the established Salon system.

During the 1860s and 1870s, Manet became a leading figure at gatherings in Parisian cafés, particularly the Café Guerbois and later the Café de la Nouvelle-Athènes. Here, he engaged in lively discussions about art and life with a younger generation of painters who admired his rebellious spirit and innovative techniques. This group included Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and Berthe Morisot.

Manet's influence on these artists was profound. His focus on modern subject matter, his increasingly loose brushwork, his interest in capturing fleeting moments, and his brighter palette (especially in the later 1860s and 1870s) provided inspiration and validation for their own experiments. His technique of alla prima (wet-on-wet painting, completed in one session) resonated with their desire for spontaneity. His willingness to challenge academic norms emboldened them to pursue their own artistic paths.

The influence, however, was reciprocal. Through his association with Monet and Morisot (who became his close friend and eventually his sister-in-law, marrying his brother Eugène), Manet's own palette lightened considerably in the 1870s. He experimented more frequently with painting en plein air (outdoors), notably during summers spent with Monet and his family at Argenteuil on the Seine. Works like "Boating" (1874) reflect this shift, capturing the leisure activities of the bourgeoisie with brighter colors and a more broken brushstroke characteristic of Impressionism.

Despite these shared interests and mutual respect, Manet maintained his distance from the official Impressionist group. He valued traditional recognition and perhaps saw the independent exhibitions as a step down from the Salon. His friendships within the group were also sometimes strained. A famous incident involved Degas painting a portrait of Manet and his wife, Suzanne Leenhoff. Manet, disliking Degas's portrayal of Suzanne, cut that portion of the canvas off, leading to a temporary but significant rift between the two strong-willed artists. Nevertheless, Manet remained a revered, if unofficial, leader for the Impressionist generation.

Evolving Themes and Style

Manet's subject matter consistently revolved around the spectacle of modern Parisian life. He painted the boulevards, the cafés and bars (A Bar at the Folies-Bergère), horse races at Longchamp, musical gatherings (Music in the Tuileries Gardens), boating excursions on the Seine, and intimate portraits of his friends and family. He depicted the bourgeoisie at leisure but also figures from the fringes of society – singers, beggars, street urchins. Unlike the Impressionists, who largely focused on landscape and leisure, Manet often imbued his scenes of modern life with a sense of ambiguity, alienation, or social commentary.

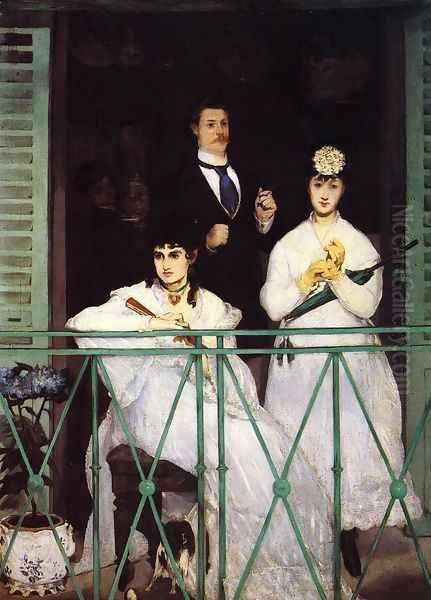

His style evolved significantly throughout his career. The early works of the 1860s are characterized by strong contrasts of light and dark, flattened forms, bold outlines, and a relatively limited palette heavily influenced by Spanish masters. Works like "The Balcony" (1868-69), with its striking green railing and enigmatic figures, showcase his interest in spatial ambiguity and unconventional composition, possibly reflecting Japanese influences.

In the 1870s, influenced by his Impressionist friends, his palette brightened, his brushwork became looser and more visible, and his interest in capturing the effects of natural light intensified. However, he never fully dissolved form into light and color as Monet did. Manet retained a strong sense of structure and a focus on the human figure. His portraits from this era, such as those of Stéphane Mallarmé and Eva Gonzalès (a pupil), combine psychological insight with a modern, direct handling of paint.

Even in his late works, Manet continued to innovate. "A Bar at the Folies-Bergère" (1882), his last major painting, is a complex masterpiece depicting a barmaid behind a marble counter, her reflection and the bustling scene of the cabaret captured in a large mirror behind her. The painting raises questions about reality and illusion, observation and alienation, through its ambiguous perspective and the barmaid's detached expression, summarizing many of his lifelong artistic concerns.

Later Life, Recognition, and Enduring Legacy

Manet's later years were increasingly marred by ill health. He suffered from the debilitating effects of untreated syphilis, likely contracted in his youth, which caused locomotor ataxia, leading to severe pain and difficulty walking. Despite his physical suffering, he continued to work, producing vibrant still lifes, particularly flower paintings, often executed in pastel, a medium better suited to his declining mobility.

Official recognition, which he had long craved, came late in his career. In 1881, partly through the efforts of his friend Antonin Proust who had become Minister of Fine Arts, Manet was awarded the Legion of Honour, France's highest civilian decoration. This acknowledgment, though belated, brought him considerable satisfaction.

His health continued to deteriorate, and in early 1883, his left leg developed gangrene. An amputation was performed, but it failed to save him. Édouard Manet died in Paris on April 30, 1883, at the age of 51. His funeral was a significant event in the Parisian art world, attended by many of the artists he had influenced and befriended, including Monet, Degas, Zola, and Mallarmé. He was buried in the Passy Cemetery in Paris.

Édouard Manet's legacy is immense. He fundamentally altered the course of Western art. By challenging the conventions of the Salon, embracing modern subject matter, and developing innovative techniques that emphasized the flat surface of the canvas and the materiality of paint, he laid the groundwork for Impressionism and subsequent modernist movements. Artists like Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse explicitly acknowledged his influence. His daring compositions, his unflinching gaze at contemporary society, and his complex position as both an insider and an outsider continue to make him a subject of fascination and study. He remains a pivotal figure, the reluctant revolutionary who, in seeking to paint his own time honestly, became a father of modern art.