Claude-Marie Dubufe (1790-1864) stands as a significant figure in French art of the 19th century, a period of profound transition and artistic innovation. Born in Paris, he emerged as one of the last prominent representatives of the Neoclassical school fostered by the renowned Jacques-Louis David. While his artistic journey began under the strong influence of Davidian classicism, Dubufe's career evolved, showcasing his versatility across historical, genre, and, most notably, portrait painting. His ability to capture the likeness and character of his sitters, particularly those from the upper echelons of French society, cemented his reputation and ensured a steady stream of prestigious commissions throughout his life.

Early Life and Artistic Formation under David

Claude-Marie Gaston Dubufe was born into a Paris that was on the cusp of revolutionary change. His artistic inclinations led him to the studio of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), the undisputed leader of the Neoclassical movement in France. David's atelier was a crucible of artistic talent, instilling in its pupils a reverence for classical antiquity, a focus on clear drawing (disegno), morally uplifting themes, and a rigorous academic approach to composition and anatomy. Dubufe absorbed these principles, which would form the bedrock of his early artistic output.

The Neoclassical style, with its emphasis on order, rationality, and heroic subject matter, was a dominant force in European art from the late 18th century through the early 19th century. Artists like David sought to revive the artistic ideals of ancient Greece and Rome, often drawing subjects from classical mythology, history, and literature. This environment shaped Dubufe's initial forays into painting, where he, like his peers, would have practiced drawing from plaster casts of antique sculptures and live models, meticulously studying anatomy and perspective.

Other notable artists who were contemporaries or slightly senior figures associated with David's school or the broader Neoclassical movement included Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), who would become a staunch defender of classicism against the rising tide of Romanticism; François Gérard (1770-1837), a highly successful portraitist and historical painter; and Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835), known for his Napoleonic-era battle scenes that began to incorporate more dynamic and emotional elements, hinting at the shift towards Romanticism. Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1767-1824) was another prominent student of David, whose work often displayed a more sensual and imaginative interpretation of classical themes.

Navigating the Salons and Gaining Recognition

After his formative years, Dubufe returned to Paris around 1812, poised to make his mark on the art world. The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to display their work and gain public and critical recognition. Success at the Salon could lead to state commissions, private patronage, and an enhanced reputation. Dubufe achieved notable success in these exhibitions, participating regularly from 1813 through much of his career, reportedly until 1865, a year after his death, which likely refers to posthumous showings or works submitted before his passing.

His early works often reflected his classical training, focusing on historical and mythological subjects. However, he soon demonstrated a versatility that allowed him to adapt to changing tastes and opportunities. The political landscape of France was turbulent during Dubufe's career, transitioning from the Napoleonic Empire to the Bourbon Restoration (under Louis XVIII and Charles X), the July Monarchy (under Louis-Philippe I), and eventually the Second Republic and Second Empire. Each regime had its own cultural priorities and favored artists, and Dubufe managed to navigate these shifts, securing patronage from various quarters.

His talent for portraiture became increasingly evident and sought after. He possessed a keen ability to render not just the physical features of his sitters but also to convey a sense of their personality and social standing. This skill made him particularly popular with the French royalty and aristocracy. He is known to have painted multiple portraits for King Louis XVIII, a significant mark of royal favor. The ability to secure such commissions was crucial for an artist's financial stability and prestige during this period.

Artistic Style: Neoclassicism and Evolving Sensibilities

Dubufe's artistic style is primarily rooted in Neoclassicism, characterized by its precise draftsmanship, smooth finish, balanced compositions, and often idealized figures. His training under David ensured a strong foundation in these principles. His lines are typically clear and controlled, and his figures possess a sculptural quality, reminiscent of classical statuary. The palette in his earlier works often adheres to the more subdued and harmonious color schemes favored by Neoclassical painters.

However, as the 19th century progressed, the artistic climate in France saw the rise of Romanticism, a movement that championed emotion, individualism, imagination, and often dramatic or exotic subject matter. Artists like Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) with his groundbreaking Raft of the Medusa, and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), known for his vibrant color and dynamic compositions, were at the forefront of this new sensibility. While Dubufe never fully embraced the passionate intensity of High Romanticism, his work, particularly his portraiture, began to show a subtle infusion of Romantic sensibilities.

This "blend" might be seen in a greater attention to the psychological depth of his sitters, a more nuanced rendering of textures, and a sophisticated use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create mood and volume. His portraits, while maintaining a sense of formal dignity, often reveal a more intimate and individualized portrayal than the stricter, more generalized representations of earlier Neoclassicism. He managed to combine the clarity and elegance of his Davidian training with a sensitivity to the evolving tastes of his clientele, who perhaps desired portraits that were not only accurate but also imbued with a certain fashionable grace and character.

Key Themes and Subjects: From Olympus to the Drawing Room

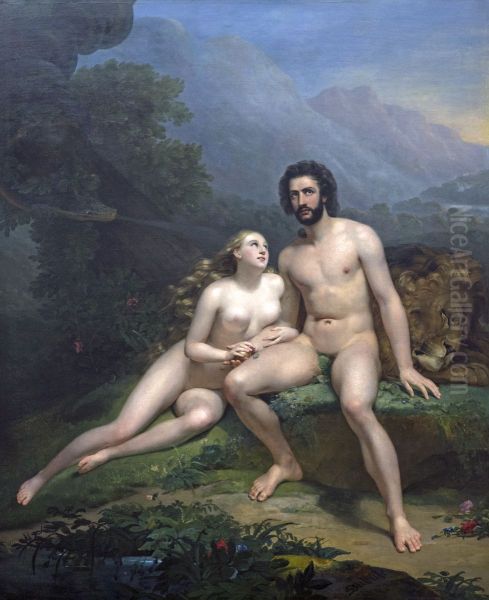

Dubufe's oeuvre spanned several genres, reflecting both his training and the demands of the art market. Initially, he tackled historical and religious subjects, which were considered the highest forms of art within the academic hierarchy. An example of his work in this vein is Adam and Eve. This painting, reportedly commissioned by Charles X, apparently caused some controversy due to its depiction of nudity, highlighting the sometimes-tenuous line artists had to walk regarding subject matter and public sensibility, even with biblical themes.

He also explored genre painting, which depicts scenes from everyday life. This genre was gaining popularity in the 19th century, offering artists a way to connect with a broader audience through relatable or sentimental narratives. However, it was in portraiture that Claude-Marie Dubufe truly excelled and built his lasting reputation. He became a favored painter of the French elite, capturing the likenesses of aristocrats, wealthy bourgeois, and prominent figures of the era.

His portraits are characterized by their elegance, refined execution, and an ability to convey the status and often the personality of the sitter. He was adept at rendering luxurious fabrics, intricate details of dress, and the subtle nuances of expression. These works served not only as personal mementos but also as public statements of identity and social standing for his clients. The demand for such portraits was high, and Dubufe's skill in this area ensured his continued success.

Notable Works: A Glimpse into Dubufe's Artistry

Several works stand out in Claude-Marie Dubufe's extensive portfolio, showcasing his skill across different subjects.

Portraits of Louis XVIII: While specific titles might vary, his commissions from the restored Bourbon monarch were significant. These official portraits would have required a blend of accurate likeness, regal dignity, and symbolic representation of power, all hallmarks of state portraiture.

Adam and Eve: This historical/religious painting is notable not only for its subject matter, drawn from the Book of Genesis, but also for the controversy it reportedly stirred. Such works allowed artists to demonstrate their mastery of anatomy and complex figural compositions, though they also risked censure if deemed to overstep contemporary moral boundaries.

Portrait of Mrs. Eyre Williams (née Jessie Gibbon): This work exemplifies his skill in society portraiture. Such paintings typically aimed to present the sitter in an elegant and flattering light, often surrounded by attributes that indicated their wealth, taste, and social position. Dubufe's ability to capture both a likeness and an air of refined sophistication would have been paramount.

The Surprise (La Surprise): This title suggests a genre scene, perhaps depicting a moment of playful interaction or an anecdotal narrative. Genre paintings often focused on everyday emotions and situations, and The Surprise likely captured a charming or intriguing moment, rendered with Dubufe's characteristic finesse.

Portrait of Joseph Fouché, Duke of Otranto: Fouché was a complex and powerful political figure who served under multiple French regimes, including the Revolution, the Empire, and the Restoration. A portrait of such a man would require capturing not just his physical appearance but also hinting at his formidable intelligence and perhaps his controversial past.

Young Woman in Distress (Jeune femme en détresse): This title points towards a more Romantic or sentimental theme, focusing on emotion. It could be a genre piece or a "tronie" (a character study), allowing Dubufe to explore the expressive potential of the human face and figure in a moment of vulnerability or sorrow.

These works, among many others, illustrate Dubufe's technical proficiency and his ability to adapt his Neoclassical training to a variety of subjects and the evolving tastes of his time.

Patronage, Royal Connections, and the Artistic Milieu

Dubufe's success was significantly bolstered by his connections to powerful patrons, including the French royal family. As mentioned, he painted for Louis XVIII, and his clientele included many members of the aristocracy and the burgeoning wealthy bourgeoisie. In the 19th century, such patronage was vital. Official commissions from the state or royalty provided not only financial reward but also immense prestige and visibility.

The artistic milieu of Paris during Dubufe's lifetime was vibrant and competitive. He would have been aware of, and in some ways competing with, a diverse range of artists. Beyond the towering figures of David, Ingres, Géricault, and Delacroix, there were many other accomplished painters. Paul Delaroche (1797-1856), for instance, became immensely popular for his historical scenes, often characterized by a meticulous, almost theatrical realism, sometimes described as the "juste milieu" (middle way) between Classicism and Romanticism. Interestingly, Delaroche was also a teacher to Dubufe's son, Édouard.

Other prominent painters included Horace Vernet (1789-1863), a prolific painter of battles, portraits, and Orientalist scenes, who enjoyed immense popularity and official favor. In the realm of portraiture, artists like Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805-1873), though slightly younger and active a bit later, became the preeminent court painter across Europe, known for his dazzlingly glamorous depictions of royalty and high society. Dubufe operated within this dynamic environment, carving out his niche as a respected portraitist and historical painter.

The Dubufe Artistic Dynasty: A Family Legacy

Claude-Marie Dubufe was not the only artist in his family; he was the progenitor of an artistic dynasty. His son, Édouard Louis Dubufe (1819-1883), also became a highly successful painter, particularly renowned for his elegant portraits of women and his historical paintings. Édouard studied initially with his father and later with Paul Delaroche. His style, while retaining a certain academic polish, often leaned more towards the Romantic and sentimental, reflecting the tastes of the mid-19th century. Édouard's works, such as The Kiss of Death and various society portraits, gained him considerable fame and fortune.

The artistic lineage continued with Claude-Marie's grandson (Édouard's son), Guillaume Dubufe (1853-1909). Guillaume also achieved success as a painter and decorator, known for his allegorical subjects, portraits, and large-scale decorative schemes, such as those for the Sorbonne and the foyer of the Comédie-Française. This continuation of artistic pursuit across three generations is a testament to the environment of creativity and professional dedication fostered within the Dubufe family.

Challenges, Criticisms, and Evolving Tastes

While Dubufe enjoyed considerable success, his career was not without its challenges. The art world of the 19th century was one of shifting tastes. The Neoclassical style, while respected, gradually gave way to the fervor of Romanticism, and later in the century, to Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), and then Impressionism. Artists trained in the academic tradition, like Dubufe, sometimes found their style perceived as less innovative or exciting compared to these newer movements.

The controversy surrounding his Adam and Eve illustrates the potential for critical backlash, even for established artists. Furthermore, the very nature of being a successful society portraitist could sometimes lead to criticism that such work was more about flattering clients than pursuing profound artistic truths. However, this view often overlooks the immense skill required to produce high-quality portraits that satisfied both the sitter's expectations and aesthetic standards. Dubufe's enduring success suggests he navigated these challenges adeptly, maintaining a loyal clientele and a respected position within the art establishment of his day.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

Claude-Marie Dubufe continued to paint throughout his life, adapting his style subtly while remaining true to his foundational training. He passed away in Paris in 1864, leaving behind a substantial body of work that documents the faces and fashions of a significant era in French history. As one of the last direct links to the studio of Jacques-Louis David, he represents an important bridge between the high Neoclassicism of the Napoleonic era and the more varied artistic landscape of the mid-19th century.

His legacy is twofold: firstly, in his own accomplished paintings, particularly his portraits, which offer valuable historical and artistic insights. Secondly, it lies in the continuation of an artistic tradition through his son Édouard and grandson Guillaume, who each made their own contributions to French art. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries who broke more radically with academic tradition, Claude-Marie Dubufe was a master craftsman, a keen observer of human character, and a significant contributor to the rich tapestry of 19th-century French painting. His works are held in various museums and private collections, attesting to his skill and the enduring appeal of his refined artistry.

Conclusion

Claude-Marie Dubufe's career exemplifies the life of a successful academic painter in 19th-century Paris. Trained in the rigorous Neoclassical tradition of David, he skillfully navigated the changing artistic and political currents of his time. While he produced notable historical and genre paintings, his most significant contribution lies in his elegant and insightful portraiture, which captured the likenesses of French royalty, aristocracy, and the influential bourgeoisie. His ability to blend classical precision with a sensitivity to individual character and contemporary aesthetics ensured his prominence. As the patriarch of an artistic dynasty, his influence extended beyond his own lifetime, leaving an indelible mark on the French art scene. His paintings remain a testament to his technical mastery and his role as a chronicler of a fascinating and transformative period in French history.