Gyula Derkovits stands as a monumental, albeit often tragic, figure in the landscape of 20th-century Hungarian art. Living a life marked by poverty, illness, and a relentless dedication to his craft, Derkovits (1894-1934) forged a unique artistic language that resonated with the social and political turmoil of his era. His paintings and graphic works, particularly his powerful woodcuts, serve as enduring testaments to the struggles of the working class and his unwavering commitment to social justice. This exploration delves into the life, influences, key works, and lasting legacy of an artist whose vision transcended his brief lifespan, securing his place as a pivotal force in modern European art.

Early Life and Formative Years in a Changing Hungary

Born in Szombathely, a town in western Hungary, on April 13, 1894, Gyula Derkovits's early life was steeped in the realities of manual labor. His father was a carpenter, and young Gyula was apprenticed to the trade, learning the skills of a joiner and furniture maker after completing his elementary education. This hands-on experience with materials and construction, though not directly artistic in its initial intent, may have subtly informed his later approach to the physicality of printmaking and the structural integrity of his compositions.

The early 20th century in Hungary was a period of immense social and political upheaval. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was creaking under internal and external pressures, and the seeds of radical change were being sown. Derkovits came of age during World War I, a conflict that would irrevocably alter the map of Europe and the psyche of its people. He served in the war and sustained injuries, an experience that undoubtedly deepened his awareness of human suffering and societal fragility. His left arm was paralyzed as a result of a wound, a significant impediment for any artist, yet one he remarkably overcame.

Following the war and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Hungary experienced a brief but intense period of revolution with the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. This revolutionary government, though short-lived, fostered a climate of cultural experimentation and support for avant-garde artistic endeavors. It was during this period that Derkovits began to formally pursue his artistic inclinations. He moved to Budapest and enrolled in Károly Kernstok's free school, Nyergesújfalu, a hub for progressive artists. Kernstok himself was a leading figure in Hungarian avant-garde painting, associated with the "Eight" (Nyolcak), a group that included artists like Róbert Berény and Dezső Czigány, who sought to bring modern French artistic trends, such as Fauvism and Cubism, into Hungarian art.

Derkovits also studied at the Haris Art Academy in Budapest, further honing his skills. His early artistic development was characterized by an absorption of various contemporary European art movements. He was not one to be confined by a single stylistic dogma; rather, he synthesized diverse influences into a personal and potent visual language.

Artistic Influences: A Confluence of European Avant-Gardes

Derkovits's artistic style is a fascinating amalgamation of several major European avant-garde currents of the early 20th century. He demonstrated a keen awareness of international artistic developments, selectively incorporating elements that resonated with his expressive needs and thematic concerns.

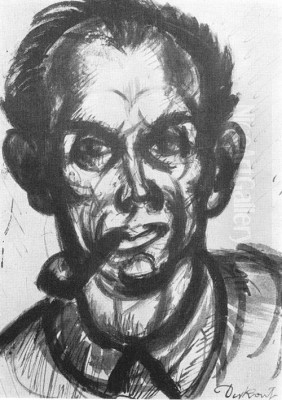

One of the most significant influences on Derkovits was German Expressionism. The raw emotional intensity, distorted forms, and bold, often non-naturalistic use of color characteristic of groups like Die Brücke (The Bridge), with artists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), featuring Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, find echoes in Derkovits's work. The profound psychological depth and social critique present in the works of artists like Oskar Kokoschka and the haunting imagery of Edvard Munch also left an indelible mark on his artistic psyche. Derkovits shared with these artists a desire to look beneath the surface of reality, to express inner turmoil, and to confront the anxieties of modern life.

The dynamism and revolutionary fervor of the Russian Avant-Garde also played a role in shaping Derkovits's vision. While he may not have directly engaged with Suprematism or Constructivism in a formal sense, the spirit of radical formal innovation and the commitment to art as a tool for social transformation were certainly in the air. More specifically, the groundbreaking cinematic techniques of Soviet filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein, particularly his use of montage, dynamic compositions, and stark visual contrasts to convey powerful narratives, are often cited as an influence on Derkovits's compositional strategies, especially in his sequential graphic works. The way he structured his images, often with a sense of urgent movement and dramatic juxtaposition, suggests an affinity with the visual language of early revolutionary cinema.

Furthermore, elements of Cubism, with its fragmented forms and multiple perspectives, and Futurism, with its celebration of dynamism and the machine age (though Derkovits's focus was more on human struggle than technological utopia), can be discerned in his handling of space and form. He was adept at creating a sense of tension and movement within his compositions, often using angular lines and overlapping planes to convey the energy and conflict inherent in his subjects. His work was not a passive reflection of these influences but an active, critical engagement, resulting in a style that was uniquely his own.

Thematic Focus: Championing the Proletariat

At the core of Gyula Derkovits's artistic output was a profound and unwavering commitment to depicting the lives, struggles, and aspirations of the working class. His art became a voice for the disenfranchised, a visual chronicle of social injustice, poverty, and the human cost of economic hardship and political oppression. This thematic focus was not merely an intellectual choice but stemmed from his own experiences and deep empathy for the common people.

His canvases and prints are populated with figures of laborers, the unemployed, families huddled in cramped tenements, and individuals bearing the weight of societal neglect. Works like The Hungry in Winter (1930) or Winter Bridge (1933) (sometimes referred to as Man with a Sack on a Winter Bridge) powerfully convey the desolation and quiet desperation of those living on the margins. The somber color palettes, often dominated by blues, grays, and earthy tones, enhance the mood of melancholy and resilience. His figures are rarely idealized; instead, they possess a raw, unvarnished dignity, their faces etched with the hardships they endure.

Derkovits's social commitment also led him to engage with historical themes, particularly those that resonated with contemporary struggles for social justice. His most famous series of woodcuts, 1514, created between 1928 and 1929, is a prime example. This series vividly recounts the story of the Hungarian peasant uprising led by György Dózsa in 1514. By choosing this historical subject, Derkovits drew parallels between past and present struggles against oppression, imbuing his work with a potent political charge. The series is not a dry historical account but a passionate and dramatic interpretation, emphasizing the brutality faced by the peasants and their heroic, albeit doomed, resistance.

His connection with leftist political movements, including the Hungarian Communist Party, further informed his socially conscious art. While his work was never mere propaganda, it undeniably carried a strong message of social critique and a call for change. He saw art as a means of bearing witness and, perhaps, of inspiring solidarity and action. This commitment to socially relevant art places him in a lineage of artists like Käthe Kollwitz in Germany or Honoré Daumier in France, who used their talents to expose injustice and advocate for the oppressed.

Mastery of Mediums: Painting and the Power of Print

Gyula Derkovits was proficient in both painting and graphic arts, but it is arguably in his woodcuts and other prints that his unique vision found its most powerful and condensed expression. His background as a joiner may have given him an innate understanding of wood, allowing him to exploit the medium's expressive potential with remarkable skill.

In his paintings, Derkovits often employed a technique that involved applying paint in thin, layered glazes, sometimes incorporating metallic paints like silver or bronze, which lent a unique luminosity and texture to his surfaces. This technique, combined with his often somber but subtly modulated color palette, created a distinctive visual effect. His compositions in painting, much like in his prints, are characterized by strong lines, dynamic arrangements of figures, and a focus on expressive gesture. Works such as Three Generations (1932) showcase his ability to convey complex human relationships and social narratives through painting, with figures that are both monumental and deeply human.

However, it is his graphic work, particularly the woodcuts, that cemented his reputation. The stark contrasts inherent in the woodcut medium – the interplay of black and white, solid form and negative space – perfectly suited Derkovits's desire for direct, impactful imagery. His lines are often sharp and angular, conveying a sense of tension and urgency. He masterfully used the grain of the wood and the act of carving to imbue his prints with a raw, almost brutal energy.

The 1514 series is a tour de force of modern printmaking. Each image in the series, such as the iconic Dózsa on the Fiery Throne, is a compact drama, filled with expressive power and narrative clarity. He utilized techniques reminiscent of cinematic close-ups and dynamic framing to heighten the emotional impact. Other notable graphic works include Terror (1930) and Court Summons (1930), which further demonstrate his ability to distill complex social and emotional states into potent visual statements. His prints were not only artistically innovative but also more accessible to a wider audience, aligning with his desire to create art that spoke to and for the common people.

Key Works and Their Enduring Significance

Several works stand out in Gyula Derkovits's oeuvre, each encapsulating different facets of his artistic genius and thematic preoccupations.

The _1514_ woodcut series (1928-1929) is undoubtedly his magnum opus in the graphic arts. Comprising several powerful images, it narrates the brutal suppression of the Hungarian peasant revolt led by György Dózsa. Derkovits’s interpretation is not merely illustrative but deeply empathetic towards the peasants' plight. The stark black and white of the woodcuts, the angular, almost violent lines, and the expressive contortions of the figures convey the raw emotion and brutality of the events. Dózsa on the Fiery Throne, depicting the rebel leader's gruesome execution, is a particularly harrowing and unforgettable image, symbolizing martyrdom and the enduring spirit of resistance. This series is a landmark in socially committed art, comparable in its impact to Goya's Disasters of War.

_The Hungry in Winter_ (c. 1930) / _Winter Bridge_ (1933): These paintings (or closely related themes) capture the bleakness of poverty during the harsh Hungarian winters. Often featuring solitary figures or small, huddled groups against desolate urban or semi-urban landscapes, these works evoke a profound sense of isolation and hardship. The use of cool, muted colors and the gaunt, weary expressions of the figures speak volumes about the daily struggle for survival faced by many during the interwar period. The figure crossing a bridge in winter, often laden with a sack, became a recurring motif, symbolizing the arduous journey of life for the underprivileged.

_Three Generations_ (1932): This painting is a poignant exploration of family, continuity, and the weight of experience across different ages. Typically depicting a child, a parent, and a grandparent, the work often carries an undercurrent of social commentary, suggesting the inherited burdens and the slim hopes for a better future within working-class families. Derkovits’s portrayal is unsentimental yet deeply moving, highlighting the resilience and interconnectedness of human lives amidst adversity.

_Terror_ (1930): This graphic work, likely a woodcut or linocut, reflects the oppressive political atmosphere of the time. While its specific subject might be open to interpretation, the title and imagery convey a sense of fear, persecution, and the ever-present threat of violence or state repression. It speaks to the anxieties of an era marked by political instability and the rise of authoritarian regimes.

_Court Summons_ (1930): Another powerful graphic piece, this work likely depicts the intimidating and often unjust encounter of ordinary individuals with the machinery of the state and its legal system. It highlights the power imbalance and the vulnerability of the common citizen when faced with bureaucratic or judicial authority, a theme that resonated deeply with Derkovits's concern for social justice.

These works, now primarily housed in major Hungarian institutions like the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest and the Budapest History Museum (Kiscelli Municipal Gallery), are not just historical artifacts. They continue to speak to contemporary audiences about the enduring issues of social inequality, the human cost of conflict, and the importance of empathy and social responsibility.

Exhibitions, Contemporary Reception, and a Life of Struggle

During his lifetime, Gyula Derkovits achieved a degree of recognition within avant-garde circles, but widespread acclaim and financial stability eluded him. He participated in various exhibitions in Budapest throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. His work, with its challenging subject matter and modernist style, was not always readily accepted by the more conservative elements of the Hungarian art establishment or the general public.

The interwar period in Hungary, under the Horthy regime, was politically conservative, and art that was perceived as too radical or critical of the social order often faced difficulties. Despite this, Derkovits persevered, driven by an inner necessity to create. He was associated with progressive artistic groups and maintained connections with other like-minded artists and intellectuals.

His personal life was marked by constant struggle. The physical ailment from his war wound, coupled with persistent poverty and recurring health problems (including tuberculosis), made his artistic endeavors all the more remarkable. He and his wife, Viktória Dombai, often lived in dire conditions, moving frequently. This precarious existence undoubtedly fueled the empathy and urgency evident in his depictions of the poor and marginalized. He died tragically young, at the age of 40, on June 18, 1934, in Budapest, due to heart failure exacerbated by his chronic illnesses and hardships.

Interactions with Contemporaries and the Broader Art World

Gyula Derkovits was not an isolated figure. He was part of a vibrant, albeit often struggling, Hungarian art scene and was aware of broader European artistic currents. His studies with Károly Kernstok connected him to the legacy of "The Eight" (Nyolcak), a group that included, besides Kernstok, figures like Róbert Berény, Dezső Orbán, and Bertalan Pór, who were instrumental in introducing Post-Impressionist and Fauvist ideas to Hungary.

While direct collaborations in the sense of co-authored artworks are not extensively documented for Derkovits, his participation in group exhibitions and his engagement with the artistic discourse of his time imply a network of professional relationships. He would have been aware of other significant Hungarian modernists, such as Lajos Kassák, a key figure in the Hungarian avant-garde and editor of the influential journal MA (Today), which promoted Constructivism and other international modernist trends. Artists like Sándor Bortnyik and Béla Uitz were also prominent in Hungarian avant-garde and socially committed art circles.

His work was exhibited alongside other Hungarian artists who explored themes of social reality and modernist expression. For instance, later museum exhibitions have retrospectively grouped him with contemporaries like István Farkas, whose art, though different in style, also possessed a haunting, melancholic quality, and Imre Ámos and György Kondor, artists who also grappled with the anxieties and spiritual crises of the era.

Internationally, Derkovits's engagement was primarily through the absorption of influences. His affinity with German Expressionists like Emil Nolde and Oskar Kokoschka, and the Norwegian Edvard Munch, suggests a deep study of their work, likely through reproductions or exhibitions that reached Budapest. The impact of Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein points to an awareness of the revolutionary potential of new media and artistic forms emerging from the Soviet Union.

There is also evidence of Hungarian-Polish artistic exchanges during this period. While specific interactions involving Derkovits might be nuanced, artists from both nations were exploring similar modernist and expressionist tendencies. Figures like the Polish artist Zygmunt Bocian or Wacław Szymański were part of a broader Central European artistic ferment. Derkovits's collaborators, as mentioned in some sources, such as Molnár C. Pál, Rauscher György, Simon György János, Csehay Wallesz Zsigmond, and Kósa Márta, would have been part of his immediate artistic milieu in Hungary, sharing exhibition spaces or artistic dialogues.

Posthumous Recognition and Enduring Legacy

While Gyula Derkovits did not achieve widespread fame or financial success during his short life, his artistic significance grew immensely in the decades following his death. His unwavering focus on the proletariat and his powerful critiques of social injustice made him a particularly resonant figure in post-World War II Hungary, especially after the communist takeover in 1948-1949.

His work was posthumously embraced by the new socialist regime, which saw in him an artistic precursor who had championed the cause of the working class. Derkovits was elevated to the status of a national icon, a key figure in the narrative of Hungarian socialist art. His art was seen as embodying the principles of socialist realism, even though his style was far more complex and nuanced than the often rigid and propagandistic art officially sanctioned under that doctrine. His expressionist tendencies and modernist innovations were sometimes downplayed in favor of his social content during this period.

Major retrospective exhibitions were organized, and his works became staples in Hungarian museums. The "Derkovits" exhibition at the Hungarian National Gallery in 2014, for example, reaffirmed his status and allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of his diverse influences and unique artistic synthesis, moving beyond earlier, more politically constrained interpretations.

Today, Gyula Derkovits is recognized not just as a Hungarian national treasure but as an important voice in 20th-century European modernism. His ability to fuse avant-garde aesthetics with profound social commentary, his mastery of both painting and printmaking, and the sheer emotional power of his imagery ensure his lasting relevance. His art continues to inspire and provoke, reminding us of the enduring power of art to bear witness to human suffering and to advocate for a more just and compassionate world. His legacy is that of an artist who, despite immense personal hardship, never wavered in his commitment to his vision and to the people whose lives he so powerfully depicted. His name is also commemorated in institutions like the Derkovits Gyula Általános Iskola (Gyula Derkovits Elementary School) and the Derkovits Art Scholarship for young artists in Hungary, ensuring his influence extends to future generations.