Edward Emerson Simmons stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of American art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter whose career bridged the elegance of the Gilded Age with the burgeoning modernism of the new era, Simmons is primarily celebrated for his contributions to the American Renaissance mural movement and his membership in the influential group known as "The Ten American Painters." His life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic currents that shaped American visual culture, from the academic traditions of Paris to the vibrant, nationalistic spirit of public art in the United States.

Early Life and Formative Education

Born on October 27, 1852, in Concord, Massachusetts, Edward Emerson Simmons was immersed in a rich New England cultural heritage. Concord itself was a crucible of American intellectualism, home to figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson (a distant relative of Simmons) and Henry David Thoreau. His father was a Unitarian minister, and this environment likely instilled in young Edward a sense of discipline and a thoughtful disposition. His mother passed away when he was young, and he was subsequently raised by his grandmother, a circumstance that may have fostered a degree of independence and introspection early in his life.

Simmons's formal education began at Harvard College, from which he graduated in 1874. While Harvard at the time did not have a dedicated fine arts program in the modern sense, the classical education he received would have provided a broad intellectual foundation. It was after Harvard that his artistic inclinations truly began to take shape. He initially pursued art studies in Boston at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, where he studied under Frank Crowninshield, a painter known for his portraits and genre scenes. This early training in Boston would have exposed him to the prevailing academic styles and the burgeoning interest in European artistic developments.

The Parisian Sojourn: Academic Rigor and Impressionist Whispers

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Simmons recognized that Paris was the undisputed center of the art world. In 1878 or 1879, he made the pilgrimage to the French capital to further hone his skills. He enrolled in the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school that served as a popular alternative to the more rigid École des Beaux-Arts. At the Académie Julian, Simmons studied under renowned academic painters Jules Joseph Lefebvre and Gustave Boulanger. Both Lefebvre, celebrated for his idealized female nudes and portraits, and Boulanger, known for his classical and Orientalist subjects, were masters of draughtsmanship and composition. Their tutelage provided Simmons with a strong foundation in academic technique, emphasizing anatomical accuracy, refined modeling, and balanced design.

During his time in Paris, Simmons also encountered the revolutionary force of Impressionism, which was still a subject of considerable debate and excitement. While his primary training was academic, the vibrant colors, broken brushwork, and focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere espoused by artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro undoubtedly made an impression. Furthermore, Simmons had a significant encounter with the expatriate American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Whistler, with his "art for art's sake" philosophy, his emphasis on tonal harmonies, and his sophisticated aestheticism, offered a compelling alternative to strict academicism and the more scientific approach of some Impressionists. Whistler's influence can be discerned in some of Simmons's later works, particularly in their subtle color palettes and atmospheric qualities.

Simmons began to achieve recognition during his Parisian years. He exhibited at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, receiving an honorable mention in 1883. This was a significant acknowledgment for a young foreign artist. He also won a substantial ,000 prize at the Second Prize Fund Exhibition in New York while still based in Europe, signaling his growing reputation back in his home country. His painting "Le Printemps" (Spring), likely from this period, showcases his academic training infused with a gentle, poetic sensibility.

Return to America and the Rise of a Muralist

Simmons returned to the United States in the early 1890s, a period often referred to as the American Renaissance. This era saw a surge in civic pride and a desire to beautify public spaces with art that reflected American ideals and achievements. Architects like Charles Follen McKim, Stanford White, and Daniel Burnham were designing grand public buildings, and there was a corresponding demand for sculptors and painters to adorn them. Mural painting, with its potential for large-scale narrative and allegorical expression, became a particularly favored medium.

Simmons quickly established himself as a leading figure in this movement. His classical training, combined with an adaptable style, made him well-suited for mural commissions. In 1894, he received a pivotal commission from the Municipal Art Society of New York to decorate the interior of the new Criminal Courts Building in Manhattan (designed by architect Napoleon LeBrun). This was the Society's first major commission, and its success was crucial. Simmons created a series of three monumental allegorical panels: "Justice," "The Fates," and "The Rights of Man." These works, with their dignified figures, balanced compositions, and clear thematic content, were widely praised and cemented his reputation as a premier muralist. "Justice," for instance, typically depicted as a blindfolded figure with scales, would have resonated with the building's function, while "The Fates" (Clotho, Lachesis, Atropos) offered a more philosophical meditation on destiny, and "The Rights of Man" spoke to core American democratic values.

Masterpieces in Public Spaces: The Library of Congress and Beyond

The success of the Criminal Courts Building murals led to further prestigious commissions. One of the most significant was for the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., a building that stands as a veritable temple to the American Renaissance, featuring work by numerous prominent artists, including John White Alexander, Gari Melchers, Elihu Vedder, and Kenyon Cox. For the Northwest Corridor of the Library's Thomas Jefferson Building, Simmons painted a series of nine lunettes depicting the Muses: Calliope (Epic Poetry), Clio (History), Erato (Love Poetry), Euterpe (Music), Melpomene (Tragedy), Polyhymnia (Sacred Poetry), Terpsichore (Dance), Thalia (Comedy), and Urania (Astronomy).

Completed around 1896, these murals were lauded for their "technical, formal, and harmonious balance." Critics noted their "thoughtful, serious, distinguished" quality, recognizing the "intellectual power behind them." Simmons's Muses are depicted as graceful, classically draped figures, each with attributes appropriate to her domain, set against serene landscapes or architectural backdrops. His style here, while rooted in academic tradition, also shows a sensitivity to color and light that hints at his Impressionist leanings. The figures are idealized yet possess a certain human warmth and accessibility.

Simmons's mural work extended to numerous other important public and private buildings. He created decorations for the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York, a symbol of Gilded Age luxury. He also painted murals for several state capitols, including the Massachusetts State House in Boston (notably "The Return of the Colors" and "Concord Bridge"), the Minnesota State Capitol in St. Paul (designed by Cass Gilbert, featuring works like "The Civilization of the Northwest"), and the South Dakota State Capitol in Pierre. His work could also be found in the Appellate Court in New York and the Walker Art Building at Bowdoin College. These commissions underscore the national reach of his reputation and the demand for his particular blend of allegorical grandeur and refined execution.

The Ten American Painters: A Collective Impressionist Voice

While excelling as a muralist, Simmons also maintained a practice as an easel painter and was keenly aware of contemporary artistic developments. In 1897, he became a founding member of "The Ten American Painters," often simply called "The Ten." This group seceded from the larger, more conservative Society of American Artists, feeling that the Society's exhibitions were overcrowded and that their own more progressive, Impressionist-influenced work was not being adequately showcased.

The formation of "The Ten" was a significant moment in the history of American Impressionism. The group was largely spearheaded by Childe Hassam, one of America's foremost Impressionists, and included other prominent artists such as John Henry Twachtman, J. Alden Weir, Frank Weston Benson, Joseph DeCamp, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Willard Metcalf, Robert Reid, and Edmund C. Tarbell. Later, William Merritt Chase would join after Twachtman's death. These artists, while diverse in their individual styles, shared a common interest in exploring the effects of light and color, often depicting landscapes, genteel interior scenes, and portraits with a brighter palette and looser brushwork than was typical of academic painting.

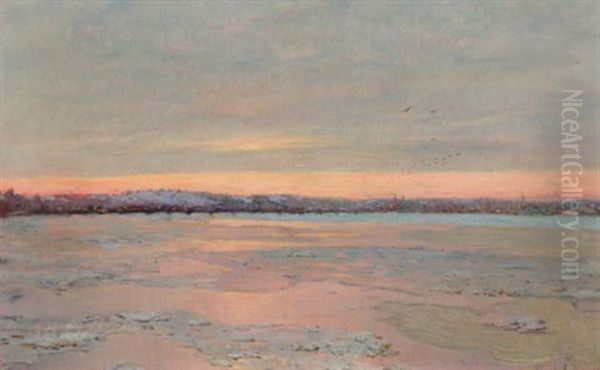

Simmons's membership in "The Ten" solidified his standing within the American avant-garde of the time. The group held annual exhibitions for two decades, providing a consistent platform for American Impressionism and helping to popularize the style with collectors and the public. While Simmons's mural work often required a more formal, allegorical approach, his easel paintings allowed him greater freedom to explore Impressionist techniques. His landscapes, such as those painted during his time in the St. Ives art colony in Cornwall, England, demonstrate his sensitivity to atmosphere and natural beauty. Works like "Winter Twilight on the Charles River" capture the subtle, poetic effects of light on a familiar American scene.

Style, Themes, and Artistic Philosophy

Edward Emerson Simmons's artistic style can be characterized as a sophisticated blend of academic classicism and American Impressionism. His rigorous training in Paris provided him with impeccable draughtsmanship and a strong sense of composition, which were essential for his large-scale mural projects. These works often featured allegorical figures rendered with a classical sense of form and dignity, suitable for their public and often didactic purpose. He aimed for a "conservative taste" in his murals, ensuring they were accessible and uplifting to a broad audience, often incorporating themes from American history and ideals.

However, Simmons was not immune to the allure of Impressionism. In his easel paintings, and even subtly within his murals, one can see a lighter palette, a concern for the effects of light and atmosphere, and a more broken brushstroke than strict academicism would permit. He had a profound understanding of natural beauty, evident in his landscapes, which often possess a lyrical, poetic quality. His painting "The Carpenter's Son" (c. 1888-1890), for example, while depicting a traditional subject, is rendered with a sensitivity to light and a realism that feels both timeless and modern.

Simmons believed in the importance of art in public life and the power of murals to educate and inspire. His participation in the American Renaissance movement was driven by a conviction that art should be integrated into the fabric of society, enhancing civic spaces and fostering a sense of shared cultural identity. His autobiography, published in 1922 as "From Seven to Seventy: Memories of a Painter and a Yankee," provides valuable insights into his artistic journey, his contemporaries, and the art world of his time. It reveals a man of intellect and strong opinions, dedicated to his craft.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Edward Emerson Simmons remained an active and respected figure in the American art world throughout the early 20th century. He continued to undertake mural commissions and exhibit his work. In his later years, he resided at Malvern Villa, a substantial thirteen-room house in Connecticut, known for its formal gardens and the lively parties hosted there. This suggests a life of comfortable success, though, like many artists of his generation whose styles were rooted in the 19th century, his work may have seemed less cutting-edge as modernist movements like Cubism and Fauvism gained traction.

Despite declining health in his final years, Simmons reportedly remained engaged in his habitual activities. He passed away on November 17, 1931, in Baltimore, Maryland, at the age of 79, leaving behind a significant body of work that adorns some of America's most important public buildings.

Edward Emerson Simmons's legacy is multifaceted. As a muralist, he was a key contributor to the American Renaissance, creating works that embodied the aspirations and ideals of his era. His murals in the Library of Congress, the Massachusetts State House, and other prominent locations continue to be admired for their technical skill and allegorical richness. As a member of "The Ten American Painters," he played a role in advancing the cause of Impressionism in the United States, helping to shift American taste towards a more modern aesthetic.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries in "The Ten," like Childe Hassam or John Singer Sargent (another great American muralist and portraitist of the era, though not a member of The Ten), Simmons's contributions were substantial. His ability to synthesize academic tradition with Impressionist sensibilities allowed him to create art that was both dignified and visually appealing, suitable for grand public statements yet imbued with a personal artistic vision. His work serves as an important bridge between 19th-century artistic conventions and the emerging modernism of the 20th century, reflecting a pivotal period of transformation in American art and culture. His paintings and murals remain a testament to a dedicated artist who skillfully navigated the diverse artistic currents of his time, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's visual heritage. Other notable contemporaries whose careers intersected or paralleled aspects of Simmons's include Edwin Blashfield, another prominent muralist, and painters like Abbott Handerson Thayer, who was also a member of The Ten. His interactions, such as viewing the work of younger artists like Xavier Martinez alongside Childe Hassam, show his continued engagement with the evolving art scene.