William Mulready stands as a significant figure in British art history, an Irish-born painter whose career spanned the transition from the Regency era to the height of the Victorian age. Born in Ennis, County Clare, Ireland, on April 1, 1786, Mulready moved with his family to London in 1792. This relocation proved pivotal, placing him at the heart of the British art world. He demonstrated artistic talent early on and, by the age of fourteen, was admitted to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1800. His long and productive life, ending in London on July 7, 1863, saw him achieve considerable fame as a painter of genre scenes, landscapes, and as a highly regarded illustrator.

Mulready's work is often characterized by its meticulous detail, narrative clarity, and a gentle, sometimes sentimental, depiction of everyday life, particularly rural and domestic scenes. He navigated the changing artistic tastes of the 19th century, absorbing influences from Dutch Masters while developing a distinctly personal style that resonated with the Victorian public. Beyond his canvases, he contributed significantly to the fields of book illustration and even postal design, leaving a multifaceted legacy that continues to be studied and appreciated.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Mulready's journey into the art world began shortly after his arrival in London. His precocious talent gained him entry into the Royal Academy Schools, the foremost art institution in Britain, founded under the patronage of King George III and guided by figures like its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Studying at the RA provided Mulready with rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and the principles of academic art, laying a strong foundation for his future career. His early years were also marked by formative relationships.

He came under the influence of the writer and philosopher William Godwin, a prominent radical thinker of the time. Godwin took an interest in the young artist and commissioned him to illustrate children's books for his Juvenile Library. This connection was significant, providing Mulready with early professional experience and exposure. Godwin even chronicled Mulready's formative years in a publication titled The Looking Glass: A True History of the Early Life of an Artist, offering valuable insight into the artist's youth and education, albeit through Godwin's own lens.

Another crucial influence during this period was the landscape painter John Varley. Mulready not only studied with Varley but also became closely associated with his circle, which included Varley's brother, Cornelius Varley, also an artist, and fellow student John Linnell. This group often engaged in sketching expeditions, particularly around Kensington Gravel Pits where Mulready and Linnell would later share lodgings. These outdoor studies honed Mulready's skills in observation and landscape depiction, even though his primary focus would eventually shift towards figurative and narrative subjects. His connection to the Varley family deepened when he married Elizabeth Varley, John and Cornelius's sister, in 1803.

Rise to Prominence: The Royal Academy and Genre Painting

Mulready first exhibited at the Royal Academy's annual exhibition in 1804, marking the public debut of a long and consistent presence at this prestigious venue. While his initial works included landscapes reflecting his studies with John Varley, a significant shift occurred around 1808. He began to turn his attention increasingly towards genre painting – scenes of everyday life, often anecdotal or humorous, featuring ordinary people in familiar settings.

This move aligned him with a growing taste in Britain for narrative art, partly inspired by the enduring popularity of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish masters like David Teniers the Younger and Adriaen van Ostade. A more direct contemporary influence and friendly rival in this field was the Scottish painter Sir David Wilkie, whose detailed and engaging depictions of peasant life and historical anecdotes had already captured the public imagination. Mulready absorbed these influences, developing his own approach characterized by careful composition, precise draughtsmanship, and an emerging sensitivity to human interaction and emotion.

His growing reputation was solidified by his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in November 1815, followed swiftly by his election as a full Royal Academician (RA) in February 1816. This rapid ascent was largely propelled by the success of his painting The Fight Interrupted (also known as Idle Boys in some contexts, though Idle Boys might refer to a different, related work), exhibited in 1815. Achieving full Academician status at the age of 29 was a remarkable accomplishment, cementing his position within the British art establishment alongside esteemed contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner and Sir Thomas Lawrence.

Mastering the Narrative: Signature Works and Themes

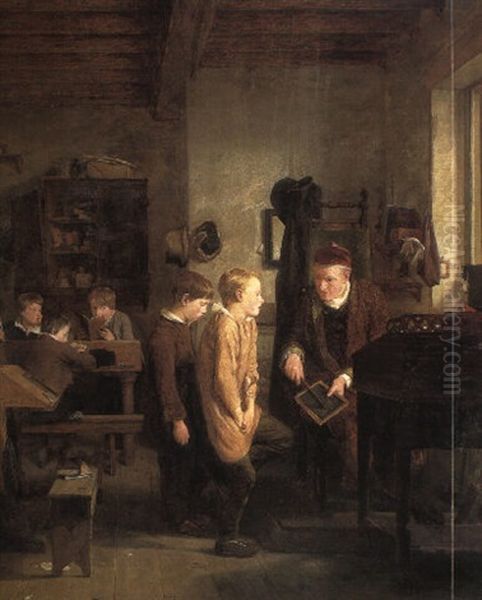

Throughout his mature career, Mulready produced a series of highly popular and critically acclaimed genre paintings that became hallmarks of his style. These works often explored themes of childhood, education, courtship, and rural life, rendered with a blend of naturalism and gentle sentimentality that appealed strongly to Victorian sensibilities. His paintings were narratives captured in a single frame, inviting viewers to interpret the story and empathize with the characters.

One of his most celebrated works is Choosing the Wedding Gown (1846), inspired by an episode in Oliver Goldsmith's novel The Vicar of Wakefield, a text Mulready also illustrated. The painting depicts a scene in a draper's shop, focusing on the interaction between the engaged couple and the shopkeeper. It is admired for its exquisite detail, rich colour, and subtle psychological portrayal of the characters. The meticulous rendering of fabrics and textures showcases his technical mastery.

Other notable works explore different facets of human experience. The Sonnet (1839) presents an intimate scene of a young man reading poetry to an attentive young woman, capturing a moment of romantic absorption. The Wolf and the Lamb (1820) uses the metaphor of a bully tormenting a smaller boy to comment on themes of power and innocence. First Love (1839) tenderly depicts the shy awkwardness of young romance. Paintings like The Last Inn (date uncertain, likely mid-career) and The Farrier's Shop (c. 1820s-30s) capture vignettes of village life, demonstrating his keen observation of social interactions and environments. Works focusing on children, such as Idle Boys (various versions/related themes) often carried a moral message about diligence versus idleness, a common preoccupation in the Victorian era.

Artistic Style and Technique

William Mulready's artistic style evolved throughout his career but consistently demonstrated a commitment to meticulous craftsmanship and detailed observation. His training at the Royal Academy instilled a strong foundation in academic drawing, particularly evident in his numerous life studies. He possessed a profound understanding of human anatomy and was known for his careful studies of figures in motion, paying close attention to the articulation of joints and the rendering of musculature, which lent authenticity to his painted figures.

Initially, Mulready employed a more direct painting technique, using relatively opaque colours and favouring earthy tones, somewhat in the manner of the Dutch masters he admired. However, particularly from the 1830s onwards, his technique shifted towards the use of richer colours and complex glazing methods. He built up layers of translucent paint over a light ground, achieving a luminous, jewel-like quality in his finished works. This approach allowed for greater depth, subtlety in modelling, and vibrancy of colour, distinguishing his later paintings. His handling of light became increasingly sophisticated, contributing to the realism and atmosphere of his scenes.

His style successfully blended naturalism with elements of Romanticism and the prevailing Victorian taste for sentiment. While he depicted everyday scenes, there was often an underlying idealization, particularly in his portrayal of rural life, which sometimes drew criticism for being overly picturesque or sanitized. Nevertheless, his ability to capture nuanced human emotions and interactions within carefully constructed compositions was widely praised. His work stands in contrast to the broader, more atmospheric effects sought by landscape contemporaries like Turner or the social realism later pursued by artists like Luke Fildes, occupying a distinct niche focused on intimate narrative and technical polish.

A Wider Canvas: Illustration and Design

Beyond his easel paintings, William Mulready made significant contributions as an illustrator, particularly for children's literature during the early part of his career. Working initially with William Godwin's Juvenile Library, he provided illustrations for popular rhymes and stories. Notable examples include The Butterfly's Ball, and the Grasshopper's Feast (1807) by William Roscoe, and its sequel The Peacock 'At Home' (1807) by Catherine Ann Dorset. These charming and finely detailed illustrations helped set a high standard for children's book illustration in the early 19th century.

His skill as an illustrator was further showcased in his designs for editions of classic literature, most famously Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield, published in 1843 with thirty-two illustrations by Mulready. These designs were highly acclaimed for their sensitivity to the text and their exquisite execution, translating the novel's blend of humour, sentiment, and social observation into visual form. His illustrations, like his paintings, were characterized by careful drawing, attention to detail, and expressive figures.

Perhaps Mulready's most unusual and widely known design contribution lay outside traditional artistic channels: the Mulready postal stationery. In 1840, as part of Rowland Hill's revolutionary postal reforms introducing the Penny Post, Mulready was commissioned to design prepaid envelopes and letter sheets. His intricate allegorical design featured Britannia at the centre, dispatching winged messengers to all corners of the globe, flanked by imagery representing the British Empire and communication. While intended as a work of high art to elevate the new postal system, the design proved immensely unpopular with the public, who found it overly elaborate and perhaps pretentious. It was widely ridiculed and parodied, quickly withdrawn from circulation and replaced by the simple adhesive stamp, the Penny Black. Despite its failure in the marketplace, the Mulready stationery remains a fascinating historical artifact and a testament to the artist's versatility.

Relationships and Collaborations

William Mulready's long career placed him within a vibrant network of artists, writers, and patrons. His early association with John Varley was pivotal, not just for his training but also for introducing him to a circle of aspiring landscape artists. His close friendship and shared living arrangement with John Linnell between 1809 and 1811 were artistically fruitful, with both artists sketching the landscapes around Kensington Gravel Pits. However, this relationship became entangled in Mulready's personal life, contributing significantly to the breakdown of his marriage.

His marriage to Elizabeth Varley, sister of John and Cornelius, was tumultuous and ultimately unhappy. They had four sons, but separated permanently around the 1820s amidst mutual accusations. Elizabeth accused Mulready of cruelty and infidelity, citing letters that suggested an inappropriate relationship with John Linnell. Mulready, in turn, made counter-accusations against his wife. This painful separation cast a shadow over his personal life, although he continued to support his children. In later life, a woman named Mary Leechy was part of his household, described sometimes as a housekeeper or companion, but the exact nature of their relationship remains unclear, adding another layer of complexity to his private affairs.

Professionally, Mulready moved within the circles of the Royal Academy, interacting with the leading artists of his day. He was a contemporary of giants like J.M.W. Turner and landscape painters such as Clarkson Stanfield and David Roberts. His genre painting practice ran parallel to, and was often compared with, that of Sir David Wilkie. He also knew younger generations of Victorian artists, including narrative painters like William Powell Frith, Augustus Egg, and Daniel Maclise, and the popular animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer. While perhaps not forming close collaborative partnerships in the way some artists did, his regular participation in RA exhibitions and activities ensured he was a well-known figure within this artistic community. His early connection with William Godwin also linked him to literary and radical circles.

Personal Life and Later Years

William Mulready's personal life was marked by early marriage, subsequent separation, and a degree of privacy regarding his later domestic arrangements. The breakdown of his marriage to Elizabeth Varley in the 1820s was a significant event, leading to a long separation, though they never formally divorced. The accusations surrounding the separation, including those involving John Linnell, suggest a period of considerable personal turmoil. Despite this, Mulready maintained responsibility for his four sons: Paul Augustus (also an artist), William Jr., Michael, and John.

Following the separation, Mulready dedicated himself intensely to his art. He became known for his methodical habits and dedication to drawing, particularly life drawing, which he continued diligently throughout his life. He resided for many years in Kensington, a district popular with artists. His household in later years included Mary Leechy, whose role has been subject to some speculation, but who appears to have been a long-term companion or housekeeper. A self-portrait depicting himself with family members, painted in the early 1820s, remained private during his lifetime, perhaps reflecting the complexities of his family situation.

He remained active as an artist into his later years, continuing to exhibit at the Royal Academy. His death on July 7, 1863, at the age of 77, was reportedly sudden, attributed to heart disease. He died in Linden Grove, Bayswater (an area near Kensington). He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in London, a resting place for many notable figures of the Victorian era. His funeral was relatively simple, reflecting perhaps a desire for privacy even at the end of his life.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

William Mulready occupies a respected place in 19th-century British art history, primarily recognized for his contributions to genre painting and illustration. He was immensely popular during his lifetime, his works admired for their technical skill, narrative charm, and relatable subject matter. His election to the Royal Academy at a young age testified to his early talent, and he remained a consistent and esteemed exhibitor for nearly six decades.

His influence can be seen in the development of Victorian genre painting. While perhaps overshadowed in dramatic scope by some contemporaries or in social commentary by later artists, Mulready excelled at the intimate portrayal of domestic life, childhood, and rural incidents. His meticulous technique, particularly his later use of rich colour and glazes, set a high standard for craftsmanship. Artists like Thomas Webster continued in a similar vein of anecdotal genre painting. His work provided a comforting, often idealized vision of English life that resonated deeply with the values and tastes of the Victorian middle class.

His illustrations, especially for children's books like The Butterfly's Ball and The Peacock 'At Home', were groundbreaking in their quality and artistry, contributing significantly to the "Golden Age" of British illustration. His designs for The Vicar of Wakefield remain classic examples of literary illustration. The Mulready postal stationery, though a commercial failure, holds a unique place in design and postal history as the world's first prepaid pictorial postal stationery, demonstrating his willingness to apply his artistic skills to new media. While some critics then and now found his work overly sentimental or lacking in profound insight, his enduring appeal lies in his masterful technique, his gentle observation of human nature, and his creation of a charming, meticulously rendered world that captured the spirit of his age.

Conclusion

William Mulready's career exemplifies the dedicated Victorian artist: technically proficient, attuned to public taste, and versatile in his output. From his early days at the Royal Academy Schools, through his rise as a leading genre painter, to his contributions as an illustrator and designer, he navigated the complex art world of 19th-century Britain with considerable success. His paintings, characterized by detailed realism, narrative clarity, and often imbued with gentle sentiment, offered viewers engaging glimpses into everyday life. While his personal life contained complexities and challenges, his professional life was marked by consistent production and recognition. Today, William Mulready is remembered as a master craftsman, a key figure in the tradition of British genre painting, and an artist whose work continues to offer insight into the visual culture and social values of the Victorian era.