Edward Reginald Frampton stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late Victorian and early Edwardian British art. A painter renowned for his ethereal murals, intricate stained-glass designs, and evocative easel paintings, Frampton carved a unique niche for himself, blending the rich traditions of medievalism with the burgeoning ideals of Symbolism. His work, characterized by its serene figures, luminous colour palettes, and profound spiritual depth, offers a compelling window into an era of artistic transition and spiritual seeking.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born in London in 1870 (some sources suggest 1872), Edward Reginald Frampton was immersed in the world of art from his earliest years. His father, Edward Frampton, was a respected ecclesiastical decorator and stained-glass artist. This familial environment undoubtedly provided the young Frampton with an early and intimate exposure to the principles of decorative art, craftsmanship, and the specific demands of working with light and colour in glass. The elder Frampton's workshop would have been a place of learning, where the son could observe the meticulous processes involved in creating art for sacred spaces.

This foundational experience in a craft-based artistic tradition was crucial. It instilled in him an appreciation for materials and techniques that would inform his later, more ambitious projects. Unlike artists who came to decorative work later in their careers, Frampton’s understanding was ingrained, allowing him to think naturally in terms of large-scale design and the integration of art within architectural settings.

His formal education took place at Brighton Grammar School. It was here that he was a contemporary of another budding artist who would achieve notoriety, albeit of a very different kind: Aubrey Beardsley. While their artistic paths would diverge significantly – Beardsley towards the decadent and monochrome, Frampton towards the spiritual and richly coloured – their shared schooling represents an interesting intersection of talents during a vibrant period of artistic ferment in Britain.

The Allure of Italy and France

To further hone his skills and broaden his artistic horizons, Frampton, like many aspiring artists of his generation, embarked on travels to the continent. Italy, with its unparalleled legacy of Renaissance art, particularly the works of the Early Renaissance masters, made a profound impression. The serene Madonnas of Fra Angelico, the narrative clarity of Giotto, and the decorative richness of artists like Benozzo Gozzoli likely resonated with Frampton’s own inclinations. The Italian Primitives, with their devotional sincerity and often flattened perspectives, offered an alternative to the academic naturalism prevalent in some quarters.

His journeys also took him to France. Here, he would have encountered the burgeoning Symbolist movement and the work of artists who were consciously turning away from Impressionism's focus on fleeting visual sensations. The monumental and allegorical murals of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes were particularly significant. Puvis’s simplified forms, muted palettes, and emphasis on conveying abstract ideas through serene, classical compositions provided a powerful model for artists seeking to create art with a deeper, more spiritual or intellectual resonance. Frampton's later mural work, with its emphasis on flat, decorative surfaces and calm, contemplative figures, shows a clear affinity with Puvis’s aesthetic.

These travels were not mere sightseeing expeditions; they were crucial periods of study and absorption, allowing Frampton to synthesize diverse influences into his own developing artistic language. He returned to Britain with a refined sensibility and a clearer vision of the kind of art he wished to create.

The Pre-Raphaelite Echo and Symbolist Harmonies

Frampton’s artistic style is often situated within the lingering influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the broader currents of European Symbolism. While the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, had largely run its course by Frampton’s formative years, its second wave, particularly the work of Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, cast a long shadow.

Burne-Jones’s dreamlike medievalism, his elongated figures, intricate patterns, and melancholic beauty, were profoundly influential on a generation of artists, Frampton included. The quest for beauty, the interest in Arthurian legends, classical myths, and biblical narratives, all filtered through a highly aestheticized lens, found a ready disciple in Frampton. His figures often possess a similar otherworldly grace, and his compositions share Burne-Jones's concern for decorative unity. One might also see parallels with the rich, decorative work of William Morris, a close associate of Burne-Jones, whose emphasis on craftsmanship and medieval revivalism permeated the Arts and Crafts movement.

Simultaneously, Frampton was attuned to the Symbolist movement, which sought to express ideas and emotions indirectly, through suggestive imagery and personal symbols, rather than direct representation. Artists like Gustave Moreau in France, with his jewel-like paintings of mythological scenes, or Fernand Khnopff in Belgium, with his enigmatic and introspective figures, were part of this broader European trend. Frampton’s work shares this desire to evoke a mood, to hint at unseen realities, and to engage the viewer on an emotional and spiritual level. His paintings often feature solitary figures in contemplative poses, set against idealized landscapes, inviting introspection.

A Distinctive Pictorial Language

Frampton’s mature style is characterized by several key elements. He favoured a relatively flat pictorial space, often eschewing deep perspective and strong chiaroscuro (the dramatic use of light and shadow). This approach lent his work a decorative quality, akin to tapestry or, indeed, stained glass. His figures are typically serene and idealized, often draped in flowing robes that emphasize line and pattern rather than anatomical realism in the academic sense.

His colour palette was often rich and luminous, yet carefully controlled. He had a particular fondness for blues, greens, and golds, creating harmonious and often tranquil effects. Even when depicting potentially dramatic scenes, a sense of calm and order pervades his compositions. This deliberate avoidance of overt drama or intense realism aligns with the Symbolist aim of creating a more contemplative and spiritual art. His technique often involved a meticulous application of paint, resulting in smooth, refined surfaces.

This stylistic approach was well-suited to his preferred subjects: religious themes, allegorical scenes, and literary or mythological narratives. He was less concerned with capturing the fleeting appearances of the everyday world, as the Impressionists were, and more interested in conveying timeless truths or evoking a sense of the sacred and the beautiful. Other British artists working in a somewhat similar vein, though with their own distinct characteristics, might include John William Waterhouse, whose romantic depictions of mythological women share a certain poetic quality, or Byam Shaw, whose work also displayed a strong decorative and narrative impulse rooted in Pre-Raphaelite traditions.

Master of the Mural: Art for Sacred and Public Spaces

It was perhaps in the field of mural painting that Frampton made his most distinctive contribution. He specialized in large-scale decorative schemes for churches and other public buildings, often employing a technique he referred to as "spirit fresco." This was a variation of tempera painting on dry plaster, allowing for a matte finish and luminous colours that were well-suited to architectural settings. He experimented extensively with his medium, reportedly using a mixture of powdered pigments with an egg-based binder, a technique that harked back to early Renaissance practices.

His murals often depicted scenes from the lives of saints, biblical narratives, or allegorical representations of virtues. A notable example includes his work for St. Peter's Church in Birstall, West Yorkshire. These commissions allowed him to work on an ambitious scale, integrating his art directly into the fabric of the building and creating immersive spiritual environments. The challenge of mural painting – working with the architecture, considering sightlines, and creating a cohesive decorative scheme – appealed to his craftsman-like sensibilities.

Following the First World War, Frampton also became known for his war memorial murals. These poignant works sought to offer solace and remembrance, often depicting themes of sacrifice, resurrection, and peace. His style, with its inherent serenity and spiritual focus, was particularly apt for such commissions. The mural in St Barnabas Church, Ranmore Common, Surrey, is another significant example of his work in this domain. In this area, he joined other artists like Frank Brangwyn, who also undertook significant mural projects, though Brangwyn's style was generally more robust and dynamic.

The Art of Light: Stained Glass Design

Given his father's profession, it is unsurprising that Edward Reginald Frampton also excelled in the design of stained glass. His understanding of the medium was profound, recognizing that stained glass is not merely a painted surface but an art form that comes alive with light. His designs share the characteristics of his paintings: graceful figures, harmonious colours, and a strong sense of decorative pattern.

He would have been acutely aware of the stained-glass revival that had been spearheaded by figures like William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, whose firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (later Morris & Co.), revolutionized the medium in the 19th century. Frampton’s work continued this tradition of high-quality, artistically ambitious stained glass. His windows often feature saints, angels, or biblical scenes, rendered with a clarity and elegance that respects the architectural setting. The leading and the inherent qualities of the glass itself were integral parts of his designs, not mere supports for painted imagery.

His experience with stained glass undoubtedly influenced his painting style, particularly his use of strong outlines, flat planes of colour, and the overall luminous quality of his work. The way colours interact when light passes through them in a window seems to have informed his approach to pigment on canvas or plaster.

Easel Paintings and Symbolic Landscapes

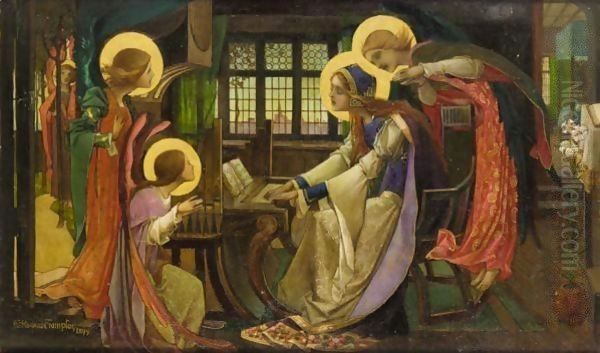

Beyond his large-scale decorative work, Frampton was also a prolific creator of easel paintings. These works often explored similar themes to his murals and stained glass: religious subjects, allegorical figures, and scenes inspired by myth and legend. Titles such as Elaine, St. Cecilia, The Annunciation, and Lamia indicate his engagement with popular literary and religious sources, often favoured by late Pre-Raphaelite and Symbolist artists.

His figures in these paintings are typically imbued with a quiet introspection. A Fanciful Landscape or The Childhood of St. Elizabeth of Hungary showcase his ability to create dreamlike, idealized settings that transport the viewer to another realm. These are not landscapes in the Impressionistic sense of capturing a specific time and place, but rather symbolic environments that enhance the mood and meaning of the figures within them.

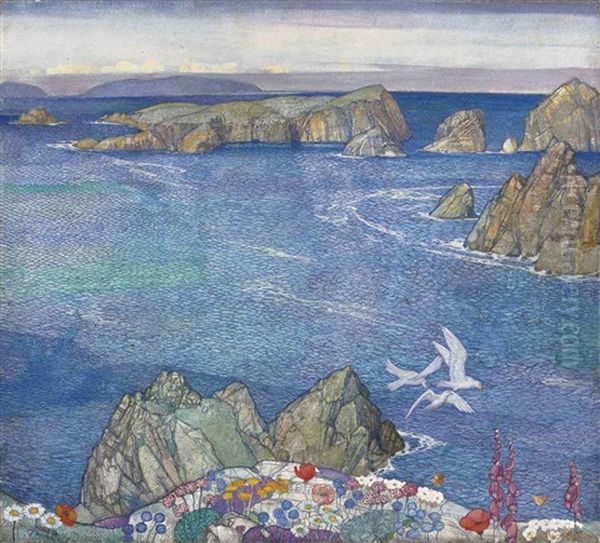

Frampton also produced pure landscapes, though these too were often filtered through his distinctive aesthetic. His painting Sark, depicting a scene from the Channel Islands, is a notable example. While based on a real location, the treatment is stylized, emphasizing pattern, serene colour harmonies, and a sense of timelessness rather than topographical accuracy. The light is often diffused, and the forms simplified, creating a poetic rather than a purely naturalistic representation. This approach to landscape has affinities with the work of some Symbolist painters who used landscape to evoke mood or spiritual states, such as certain works by the Belgian Symbolist William Degouve de Nuncques or even the more mystical landscapes of George Frederic Watts.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Contemporaries

Edward Reginald Frampton achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. He exhibited regularly at prestigious venues such as the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the Paris Salon, and various international exhibitions. This exposure brought his work to a wider audience and solidified his reputation as a significant artist of his time. His paintings were acquired by public collections, and he received commissions from important patrons.

He was part of a vibrant artistic milieu in Britain. While he may not have been a member of a specific, tightly-knit artistic group in the same way as the original Pre-Raphaelites, his work resonated with the broader trends of the Aesthetic Movement and Symbolism. He would have been aware of, and likely known, many of an older generation like Frederic Leighton or G.F. Watts, whose allegorical and symbolic works held considerable sway.

Among his closer contemporaries, one might consider artists like Walter Crane, known for his illustrative and decorative work, or Robert Anning Bell, who also worked across painting, illustration, and decorative arts including mosaics and stained glass. While each artist had their individual style, they shared a common interest in decorative principles, narrative content, and a move away from strict academic realism towards more imaginative and symbolic forms of expression. The Irish artist John Duncan, with his Celtic-inspired Symbolist paintings, also shares some thematic and stylistic affinities with Frampton's more mystical leanings.

Thematic Concerns: Spirituality and the Quest for Beauty

A central thread running through Frampton's oeuvre is a profound sense of spirituality and a dedicated quest for beauty. His religious subjects are treated with reverence and a gentle piety, avoiding didacticism or overt sentimentality. Instead, he sought to evoke a sense of the sacred through serene compositions, harmonious colours, and idealized figures. Works like Christ in Majesty or depictions of the Madonna and Child are imbued with a quiet dignity and grace.

His allegorical paintings often explore universal themes such as love, faith, hope, or the passage of time. These are not presented as complex intellectual puzzles but rather as visual meditations, inviting contemplation. The female figures in his work, often depicted as saints, muses, or personifications of virtues, are typically ethereal and otherworldly, embodying ideals of purity and spiritual grace.

This focus on the spiritual and the beautiful can be seen as a response to the increasing industrialization and materialism of the age. Like many artists and writers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Frampton sought refuge and meaning in art that transcended the mundane, offering glimpses of a more harmonious and spiritually resonant world. His art aimed to uplift and inspire, to create oases of calm and beauty in a rapidly changing society.

Later Life and Premature End

Despite a productive and well-regarded career, Edward Reginald Frampton’s life was cut relatively short. He passed away in 1923, at the age of 52 or 53. His death at a comparatively young age meant that his artistic development was curtailed, leaving one to speculate on how his style might have evolved had he lived longer, particularly in the face of the dramatic artistic shifts brought about by Modernism in the post-war era.

His son, Meredith Frampton (1894–1984), also became a distinguished painter, though his style was markedly different. Meredith Frampton was known for his meticulously detailed and highly polished portraits and still lifes, a form of precise realism that stood in contrast to his father's more Symbolist and decorative approach. This generational shift in artistic style is itself an interesting reflection of the changing art world of the 20th century.

Legacy and Modern Reappraisal

For a period in the mid-20th century, as tastes shifted decisively towards Modernism and abstraction, artists like Edward Reginald Frampton, with their roots in Victorian romanticism and Symbolism, fell somewhat out of critical favour. However, in more recent decades, there has been a growing reappraisal of this period of British art. Scholars and curators have begun to re-evaluate the contributions of artists who worked outside the main currents of avant-garde modernism, recognizing their unique qualities and historical significance.

Frampton's work is now increasingly appreciated for its distinctive blend of craftsmanship, spiritual depth, and decorative beauty. His murals, where they survive, are valued as important examples of early 20th-century ecclesiastical art. Conservation efforts, such as those undertaken for his murals in St. Peter's, Birstall, highlight a renewed interest in preserving his artistic legacy. His easel paintings and designs for stained glass appear in exhibitions and are sought after by collectors.

He is recognized as an important figure within the British Symbolist movement, an artist who successfully translated the ideals of Symbolism into large-scale decorative schemes and intimate easel paintings. His ability to create serene and spiritually uplifting art, characterized by its luminous colour and graceful forms, ensures his enduring appeal. Artists like John Duncan in Scotland, or even earlier figures like Simeon Solomon with his mystical and androgynous figures, can be seen as part of a similar lineage of British artists exploring spiritual and mythological themes with a highly aestheticized sensibility.

Conclusion: An Enduring Light

Edward Reginald Frampton was an artist of quiet conviction and refined sensibility. He navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, drawing inspiration from the medieval past, the legacy of the Pre-Raphaelites, and the contemporary ideals of European Symbolism, yet forging a style that was distinctly his own. His dedication to craftsmanship, his profound spiritual feeling, and his unwavering pursuit of beauty resulted in a body of work that continues to resonate.

Whether in the ethereal glow of his stained-glass windows, the serene grandeur of his church murals, or the contemplative beauty of his easel paintings, Frampton’s art offers a tranquil counterpoint to the often-turbulent narratives of art history. He remains a testament to the enduring power of art to elevate the human spirit and to create spaces, both physical and imaginative, where beauty and contemplation can flourish. His legacy is one of luminous colour, graceful forms, and a gentle, enduring spirituality that continues to captivate those who encounter his work.