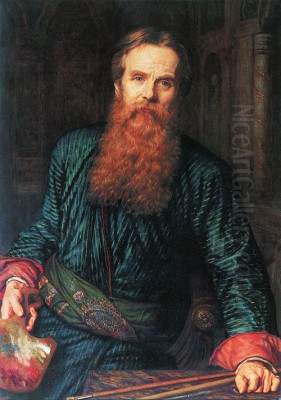

William Holman Hunt stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. Born in London in 1827, he emerged during the vibrant, complex Victorian era, a time of immense industrial change, social upheaval, and intense religious debate. Hunt was not merely a painter; he was a visionary, a reformer, and one of the principal founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an artistic movement that sought to revolutionize the art world of its time. His life and work were characterized by an unwavering commitment to truth, meticulous detail, profound symbolism, and deeply held religious convictions.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

William Holman Hunt was born on April 2, 1827, in Cheapside, London. His father, William Hunt, was a warehouse manager, and initially, the young Hunt was destined for a career in commerce, working as a clerk from a young age. However, his passion for art could not be suppressed. Despite his father's disapproval, Hunt harbored artistic ambitions, taking drawing lessons in his spare time and visiting galleries whenever possible. This early conflict between familial expectation and personal calling would forge a determined character, essential for the challenges ahead.

His persistence paid off. After initially being rejected, Hunt finally gained admission to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1844. This institution was the bastion of artistic orthodoxy in Britain, heavily influenced by the legacy of its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds. The Academy promoted an idealized style derived from High Renaissance masters like Raphael Sanzio, emphasizing generalized forms, harmonious compositions, and often somber palettes inspired by Old Masters such as Titian or Rembrandt. It was within this environment that Hunt began to question the prevailing artistic doctrines.

The Genesis of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

At the Royal Academy Schools, Hunt encountered two other young artists who shared his growing dissatisfaction with the academic status quo: John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Millais was a prodigious talent, having entered the Academy at the unprecedented age of eleven. Rossetti, a poet as well as a painter, possessed a charismatic personality and a fervent imagination drawn to medieval romanticism. Together, these three formed the nucleus of a revolutionary group.

In 1848, Hunt, Millais, and Rossetti, along with four other like-minded individuals – James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens (later an art critic), Thomas Woolner (a sculptor), and William Michael Rossetti (Dante Gabriel's brother, a writer and critic) – formally established the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). Their name declared their mission: to reject the perceived artistic corruption that began with Raphael and his followers, and to return to the perceived purity, sincerity, and detailed naturalism of Italian art before Raphael – the art of the Quattrocento masters like Fra Angelico, Sandro Botticelli, and Perugino.

The PRB's core tenets, heavily influenced by the writings of the prominent art critic John Ruskin, particularly his exhortation in Modern Painters to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart... rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing," included: having genuine ideas to express; studying Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them; sympathizing with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote; and most indispensable of all, producing thoroughly good pictures and statues. They advocated for bright, jewel-like colors applied over a wet white ground, meticulous attention to detail, complex compositions, and the choice of serious, often moral or religious, subjects.

Hunt's Pre-Raphaelite Principles in Practice

Of all the founding members, William Holman Hunt remained the most steadfastly loyal to the original principles of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood throughout his long career. His commitment to "truth to nature" was absolute, often leading him to endure significant hardship to capture authentic detail and light. He developed a painstaking technique, applying paint in thin glazes over a wet white ground to achieve the luminous, high-keyed palette characteristic of the PRB.

His early works demonstrated this burgeoning style. Rienzi vowing to obtain justice for the death of his young brother, slain in a skirmish between the Colonna and the Orsini factions (1848-49), exhibited the year after the PRB's formation, showcased the group's interest in historical subjects imbued with moral weight, rendered with sharp focus and vibrant color. Claudio and Isabella (1850-53), based on a tense scene from Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, explored themes of morality, sacrifice, and psychological tension with intense detail, particularly in the rendering of textures and expressions.

Another early work, Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1851), based on Shakespeare's Two Gentlemen of Verona, further exemplified the Pre-Raphaelite approach. Hunt depicted the dramatic moment with clarity and detail, focusing on the emotional states of the characters and the natural setting, painted outdoors in Knole Park, Kent, adhering strictly to the principle of direct observation. These early paintings, while sometimes criticized for their perceived awkwardness or harshness, laid the groundwork for the major masterpieces to come.

Masterworks of Moral and Religious Significance

Hunt's deep religious faith became a central driving force in his art. He saw painting not merely as aesthetic expression but as a moral and spiritual calling. This conviction fueled the creation of some of the most iconic religious images of the Victorian era.

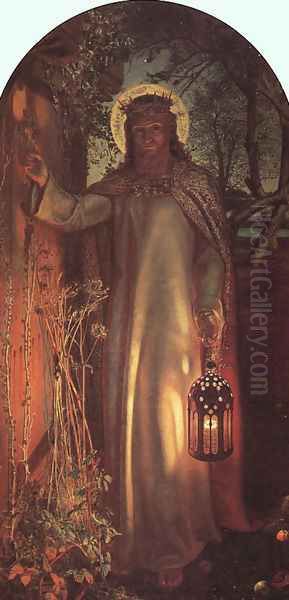

The Light of the World

Perhaps Hunt's most famous painting, The Light of the World (versions painted 1851-53 and later), is an allegorical representation of Christ knocking at the door of the human soul. Based on Revelation 3:20 ("Behold, I stand at the door, and knock..."), the painting is laden with intricate symbolism. Christ, crowned with thorns intertwined with the promise of glory, holds a lantern representing the light of conscience. He knocks on a door overgrown with weeds, symbolizing the closed-off human heart, a door that notably lacks an external handle – it can only be opened from within.

Hunt painted the figure of Christ and the lantern light meticulously by moonlight over many months to capture the specific nocturnal effect. The painting initially met with mixed reactions, but John Ruskin's passionate defense and explanation of its symbolism helped secure its fame. It became one of the most reproduced and beloved religious images of the nineteenth century, with versions now housed in Keble College, Oxford, St Paul's Cathedral, London, and Manchester Art Gallery. Its enduring power lies in its combination of detailed realism and profound spiritual allegory.

The Awakening Conscience

Painted concurrently with The Light of the World, The Awakening Conscience (1853) serves as its contemporary, secular counterpart. It depicts a "kept woman," a mistress, springing up from her lover's lap, caught in a moment of sudden moral realization. Sunlight streams into the richly furnished but morally compromised interior, illuminating her face as she gazes towards the redemptive light of the garden outside. The painting is filled with symbolic details: the discarded glove on the floor, the tangled yarn, the cat toying with a bird under the table, the popular sheet music ("Oft in the Stilly Night") hinting at lost innocence.

This depiction of a "fallen woman" experiencing a moment of potential redemption was controversial. Critics found the subject matter distasteful and the detailed realism unsettling. Again, Ruskin came to Hunt's defense, interpreting the painting's intricate symbolism and highlighting its moral seriousness. Housed in the Tate Britain, London, it remains a powerful commentary on Victorian morality and the possibility of spiritual change, rendered with intense Pre-Raphaelite detail.

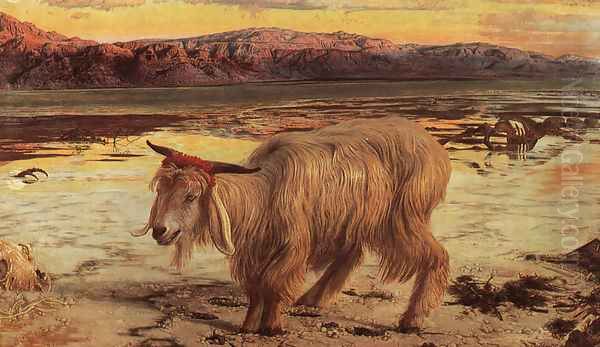

The Scapegoat

Hunt's commitment to authenticity led him on arduous journeys. In 1854, he traveled to the Holy Land, seeking to paint biblical scenes with ethnographic and topographical accuracy. One of the most dramatic outcomes of this trip was The Scapegoat (versions 1854-56). Based on the ritual described in Leviticus 16, where a goat symbolically carried the sins of the community into the wilderness, Hunt painted the scene on the desolate shores of the Dead Sea.

He endured extreme conditions, heat, and danger from bandits to capture the saline landscape and the dying goat (he used several goats for studies) with unflinching realism. The painting is a stark image of suffering and desolation, the goat burdened by a scarlet fillet, representing sin, abandoned in a barren, deathly landscape under an oppressive sky. It was interpreted variously as a symbol of Christ's sacrifice or, as Hunt perhaps intended, a metaphor for the dedicated artist rejected by society. Its harsh realism and bleak subject matter bewildered many critics, but it stands as a testament to Hunt's uncompromising vision and his physical dedication to his art. The primary version is in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, with a smaller version featuring a dark-haired goat in Manchester Art Gallery.

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple

Resulting from the same period of travel and research in the Middle East, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1854-60) depicts the biblical episode where the young Jesus is found debating with the learned rabbis in the Temple of Jerusalem (Luke 2:41-52). Hunt invested immense effort in achieving historical and cultural accuracy, studying local architecture, clothing, and physiognomy. He used local Jewish models in Jerusalem for many of the figures.

The painting is remarkable for its vibrant color, intricate detail, and the psychological interaction between the figures – the earnest young Jesus, the astonished rabbis, and his anxious parents, Mary and Joseph, arriving at the right. Completed after six years of labor, it was exhibited to great acclaim and commercial success, sold for the then-staggering sum of 5,500 guineas. Now in the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, it represents the culmination of Hunt's desire to infuse biblical narrative with tangible reality through Pre-Raphaelite principles.

Later Works and Evolving Style

While Hunt remained true to PRB principles, his later work continued to explore complex themes, often returning to subjects over many years. The Shadow of Death (1870-73), another product of his time in the Holy Land, depicts a muscular Jesus as a carpenter, stretching after work in his Nazareth workshop. The setting sun casts his shadow on the wall behind him, prefiguring the crucifixion, while Mary kneels before a chest containing the gifts of the Magi, contemplating her son's destiny. The painting combines intense realism in the depiction of the workshop and Christ's physique with profound religious foreshadowing.

Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1868), based on a poem by John Keats (which itself drew from Boccaccio), depicts the tragic heroine mourning over the pot containing the severed head of her murdered lover. Hunt renders Isabella's grief and devotion with sensitivity, surrounded by richly decorated maiolica pottery and textiles, showcasing his continued mastery of detail and texture.

The Lady of Shalott occupied Hunt intermittently for decades, culminating in a large version completed between 1886 and 1905. Based on Alfred, Lord Tennyson's famous poem, it captures the dramatic moment when the Lady, cursed to view the world only through a mirror, defies the curse to look directly at Sir Lancelot. The threads of her tapestry fly around her as the mirror cracks, sealing her doom. The painting is a whirlwind of detail and symbolic imagery, exploring themes of artistic isolation, forbidden love, and fate.

Throughout his later career, Hunt continued to travel, including further trips to the Middle East and visits to Italy and Greece, always seeking authentic settings and details for his work. While his output slowed in later years, partly due to failing eyesight, his dedication to his craft and his core artistic beliefs never wavered.

Technical Innovations and Material Concerns

Hunt's meticulousness extended beyond observation to the very materials of his craft. He was deeply concerned about the poor quality and lack of permanence of many commercially available artists' pigments in the Victorian era. He believed that the brilliance and longevity seen in the works of early masters were due to their careful preparation and use of pure materials.

He researched historical painting techniques and experimented with pigments and mediums, advocating for the use of stable, pure colors and sound technical practices. He criticized fellow artists, including members of the Royal Academy like Sir Charles Lock Eastlake, for using fugitive pigments and unsound mediums like bitumen, which led to the darkening and cracking of many contemporary paintings. Hunt's insistence on quality materials and durable techniques was an integral part of the Pre-Raphaelite commitment to honesty and craftsmanship. He was involved in efforts to establish suppliers of reliable artists' materials, reflecting his holistic approach to creating art of lasting value.

Relationships and Collaborations

The intense comradeship of the early PRB inevitably evolved. Hunt's relationship with John Everett Millais was initially very close; they shared studios and supported each other's work. However, Millais's path diverged. He achieved immense popular success, was elected to the Royal Academy (eventually becoming its President), and his style gradually moved away from the rigors of early Pre-Raphaelitism towards a looser, more conventional approach, sometimes tinged with sentimentality. While they remained connected, their artistic visions grew apart.

Hunt's relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti was perhaps more complex. Rossetti's art increasingly focused on medieval romanticism, sensuous female figures, and poetic intensity, moving towards the Aesthetic Movement. While Hunt respected Rossetti's genius, he sometimes disapproved of the perceived lack of moral seriousness or the departure from strict naturalism in Rossetti's later work. Hunt remained closer in spirit to artists like Ford Madox Brown, an older painter closely associated with the PRB though never an official member, who shared Hunt's commitment to detailed realism and serious themes. Hunt documented the history of the movement and his relationships within it in his memoirs, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1905).

Controversies and Critical Reception

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood faced intense criticism in its early years. Their work was attacked for its bright colors (seen as garish), sharp details (seen as primitive or ugly), and perceived rejection of established artistic conventions derived from masters like Raphael and later figures such as Nicolas Poussin or Claude Lorrain. Critics, including Charles Dickens, lambasted their perceived medievalism and awkwardness. Hunt's work, particularly The Awakening Conscience and The Scapegoat, drew significant controversy due to their challenging subject matter and uncompromising style.

The crucial intervention of John Ruskin, the most influential art critic of the day, proved vital. Ruskin defended the PRB in letters to The Times and in pamphlets, praising their commitment to "truth to nature" and their detailed execution, comparing them favorably to the early Italian masters they admired. His support helped turn the tide of public opinion.

Despite achieving fame and recognition later in life, including receiving the Order of Merit in 1905, Hunt's reputation, like that of the PRB generally, declined in the early twentieth century with the rise of Modernism. His meticulous realism and overt moralizing seemed out of step with new artistic trends focusing on abstraction, formalism, and subjective experience, championed by artists like Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse. However, from the mid-twentieth century onwards, there has been a significant reassessment and revival of interest in Victorian art, and Hunt's work is now recognized for its technical brilliance, psychological depth, and historical importance.

Influence and Legacy

William Holman Hunt's influence extends far beyond his own canvases. As a founder and the most persistent adherent of Pre-Raphaelitism, he played a crucial role in challenging the artistic norms of his time and revitalizing British painting. The PRB's emphasis on detail, bright color, and serious subjects had a wide impact, influencing not only painters like Edward Burne-Jones and Arthur Hughes but also decorative arts through figures like William Morris, who shared the commitment to craftsmanship and medieval inspiration.

Hunt's dedication to religious and moral themes provided a powerful counterpoint to the growing secularism and aestheticism of the later nineteenth century. His insistence on authenticity, including his travels to the Holy Land, set a new standard for historical and biblical painting. His technical concerns contributed to a greater awareness among artists of the importance of materials and sound craftsmanship.

While the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as a formal entity was short-lived, its spirit, largely embodied by Hunt's unwavering commitment, resonated through Victorian culture and beyond. His work continues to fascinate viewers with its combination of intense realism, complex symbolism, and profound conviction. He remains a key figure for understanding the intersections of art, religion, and society in the Victorian era, a painter whose dedication to his unique vision created some of the most memorable and enduring images in British art history. He passed away on September 7, 1910, leaving behind a legacy of artistic integrity and powerful visual storytelling.

Conclusion

William Holman Hunt was more than just a painter; he was a man driven by a powerful sense of purpose. From his early rebellion against a commercial career to his co-founding of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and his lifelong dedication to its principles, Hunt pursued his artistic and moral vision with extraordinary tenacity. His meticulous attention to detail, his innovative use of color and light, his profound engagement with religious and ethical themes, and his willingness to endure hardship for the sake of authenticity mark him as a unique figure. Though sometimes controversial and subject to shifting critical fortunes, his major works like The Light of the World, The Awakening Conscience, and The Scapegoat remain potent images that continue to engage and challenge audiences. Hunt's unwavering commitment to "truth to nature" and moral seriousness ensures his lasting importance in the annals of art history.