Virgilio Tojetti (1849-1901) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late 19th-century art, a painter whose career bridged the artistic traditions of Italy and France with the burgeoning cultural ambitions of Gilded Age America. Born into an artistic family in Rome, Tojetti absorbed the rich visual heritage of his native city before honing his skills under the premier academic masters of Paris. His subsequent emigration to the United States saw him become a sought-after decorative artist, adorning the opulent interiors of hotels, private residences, and religious institutions with his elegant murals and easel paintings. His work, characterized by a refined classicism, romantic sensibility, and meticulous execution, reflects both his European training and his adaptation to the tastes and demands of his American clientele.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Europe

Virgilio Tojetti was born in Rome, Italy, on March 15, 1849. His artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age by his father, Domenico Tojetti (1807-1892), himself a respected painter known for his historical and religious subjects, as well as decorative work. Domenico had worked on significant commissions, including frescoes in Roman churches like Sant'Agnese fuori le mura and the Basilica di San Paolo fuori le Mura. This familial environment provided Virgilio with his initial artistic instruction and a deep immersion in the classical and Renaissance traditions that permeated Rome. The elder Tojetti's own career would later take him to America, specifically California, where he became a prominent figure in the San Francisco art scene.

Seeking to further refine his talents, Virgilio Tojetti, like many aspiring artists of his generation, was drawn to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the 19th century. There, he enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of French academic art. His tutelage under two of the era's most celebrated and influential academic painters, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) and William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905), was formative.

Jean-Léon Gérôme was renowned for his meticulously detailed historical scenes, Orientalist subjects, and classical genre paintings. His emphasis on precise draftsmanship, smooth finish (fini), and historical accuracy left an indelible mark on his students. Bouguereau, similarly, was a master of idealized human form, particularly in his mythological and allegorical paintings, and his sentimental depictions of peasant girls. He was celebrated for his technical virtuosity, his subtle modeling of flesh, and his harmonious compositions. The influence of both masters can be discerned in Tojetti's later work: the careful attention to anatomical accuracy and detail from Gérôme, and the graceful, often idealized, portrayal of figures, particularly female nudes and cherubic putti, reminiscent of Bouguereau. Other prominent academic artists of the time, such as Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889) and Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), further defined the prevailing artistic climate in which Tojetti trained, one that valued technical skill, historical and mythological themes, and a polished aesthetic.

Emigration to America and the Gilded Age Context

In 1870, at the age of approximately 21, Virgilio Tojetti made the pivotal decision to emigrate to the United States. This move coincided with the beginning of America's Gilded Age, a period of rapid industrialization, economic expansion, and the accumulation of vast fortunes by industrialists and financiers. This new class of American elite sought to emulate European aristocracy in their lifestyles, commissioning palatial homes, grand public buildings, and luxurious hotels, all requiring elaborate decoration.

Tojetti initially settled in New York City, which was rapidly becoming the cultural and financial capital of the nation. His European training and demonstrable skill in academic and decorative painting made him well-suited to meet the demands of this new market. American taste at the time leaned heavily towards European styles, and an artist with Tojetti's pedigree found a receptive audience. He arrived at a time when other European-trained artists, or American artists returning from studies abroad, were also shaping the artistic landscape. Figures like John La Farge (1835-1910), known for his murals and stained glass, and later, Edwin Howland Blashfield (1848-1936) and Kenyon Cox (1856-1919), would become leading figures in the American mural movement, often working in styles that shared common roots with Tojetti's academic background.

The demand for decorative painting was immense. Hotels aimed to be veritable palaces, private mansions required ceilings and walls adorned with allegorical scenes, and even public buildings sought the gravitas that murals could provide. Tojetti's ability to work on a large scale, combined with his refined aesthetic, positioned him perfectly to capitalize on these opportunities.

A Master of Decorative Painting: Major Commissions

Virgilio Tojetti quickly established himself as a prominent decorative painter in New York and beyond. His work graced the interiors of some of the most prestigious establishments and homes of the era.

The Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room Ceiling

One of Tojetti's most celebrated surviving decorative works is the ceiling he painted for the dressing room of Arabella Worsham, later the wife of railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington, in her house at 4 West 54th Street, New York. The house was later sold to John D. Rockefeller. Created around 1881-1882, this exquisite work is now preserved in the Museum of the City of New York. The dressing room itself was a masterpiece of the Aesthetic Movement, designed and executed by George A. Schastey & Co., a prominent firm of cabinetmakers and decorators with whom Tojetti frequently collaborated.

Tojetti's contribution to this "Gesamtkunstwerk" (total work of art) was a magnificent satinwood ceiling panel, intricately painted with ethereal, winged putti or cupids frolicking amongst delicate floral garlands and ribbons, against a gilded background. The figures are rendered with the soft modeling and graceful charm characteristic of his style, clearly showing the influence of Bouguereau. The overall effect is one of light, airiness, and refined sensuality, perfectly embodying the Aesthetic Movement's emphasis on beauty and artistic harmony in everyday surroundings. The use of luxurious materials and the integration of painting with the room's overall decorative scheme, which included mother-of-pearl and intricate marquetry, highlight the collaborative nature of such Gilded Age projects. This work demonstrates Tojetti's mastery in creating decorative schemes that were both opulent and elegant.

Grand Hotel Murals: The Waldorf and Savoy

Tojetti's talents were also sought for the decoration of New York's grand hotels, which were symbols of the city's wealth and sophistication. He is documented as having executed significant mural work for the original Waldorf Hotel (later part of the Waldorf-Astoria) and the Savoy Hotel. While many of these original interiors have been altered or demolished over time, contemporary accounts attest to the splendor of his contributions.

These hotel murals likely featured allegorical figures, mythological scenes, or idyllic landscapes, themes popular in academic and decorative art of the period. They would have been designed to create an atmosphere of luxury, culture, and escapism for the hotel's affluent clientele. The scale of these commissions would have been considerable, requiring Tojetti to work with assistants and to adapt his studio practices to the demands of large-scale architectural decoration. His work in these prominent public spaces would have further solidified his reputation. The tradition of grand hotel decoration was international, with artists like Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931) also contributing to the opulent interiors of Parisian establishments, reflecting a shared taste for lavish embellishment.

The Ponce de Leon Hotel, St. Augustine, Florida

Perhaps one of Tojetti's most ambitious and historically significant commissions was for the Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine, Florida. Built by oil and railroad magnate Henry Flagler and opened in 1888, the Ponce de Leon was a pioneering luxury resort, a masterpiece of Spanish Renaissance Revival architecture designed by Carrère and Hastings. Flagler enlisted a team of renowned artists and craftsmen to adorn its interiors, including Tojetti, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1912) for stained glass, and George W. Maynard (1843-1923) for other murals.

Tojetti was responsible for several large murals in the hotel's rotunda and dining room ceilings. These works depicted allegorical and historical scenes related to Florida's history, particularly its Spanish colonial past and the legend of Juan Ponce de León's quest for the Fountain of Youth. The murals were praised for their vibrant colors, dynamic compositions, and the graceful rendering of figures, including angels and personifications of virtues or historical events. For instance, one of the domed ceilings featured female figures representing the Four Elements, while others depicted scenes from St. Augustine's history.

These murals were a testament to Tojetti's ability to integrate his art with complex architectural spaces and to tackle grand historical and allegorical themes. They contributed significantly to the hotel's reputation as one of the most opulent and artistically significant buildings of its time. Unfortunately, the Ponce de Leon Hotel's murals suffered over the decades from Florida's humid climate and occasional storms. Some were damaged, and reports indicate that significant portions, if not all, of Tojetti's work there were eventually lost or heavily compromised, with some sources citing Hurricane Alicia in 1983 as causing final destruction to remaining elements, though this hurricane primarily impacted Texas, suggesting a possible conflation or earlier damage from other storms. The hotel itself is now part of Flagler College, and efforts have been made to preserve its artistic heritage.

Religious Murals: The Miraculous Medal Shrine

Beyond secular decorations, Virgilio Tojetti also undertook significant religious commissions. His European Catholic upbringing and familiarity with the traditions of religious art made him a suitable choice for such projects. One notable example is his work for the Miraculous Medal Shrine (also known as the Central Shrine of the Immaculate Conception or St. Vincent's Seminary Chapel) in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

For this shrine, Tojetti painted a series of murals in the 1890s, depicting scenes central to Marian devotion. These included:

The Annunciation: The angel Gabriel announcing to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive a son.

The Madonna and Child: A classic depiction of Mary with the infant Jesus.

The Madonna and Child with St. John: A variation including the young John the Baptist.

The Apparition of the Virgin to St. Catherine Labouré: Depicting the vision that led to the creation of the Miraculous Medal.

The Immaculate Conception: The doctrine of Mary being conceived without original sin.

The Nativity of the Virgin: The birth of Mary.

These murals, likely executed in oil on canvas and then applied to the walls (marouflage), showcase Tojetti's skill in religious iconography. His figures would have been rendered with the piety and grace expected for such subjects, drawing on a long tradition of religious painting from Renaissance masters like Raphael (1483-1520) and Michelangelo (1475-1564) through to the academic religious art of his own teachers. These late works demonstrate his continued activity and reputation in providing art for significant religious spaces.

Easel Paintings and Genre Scenes

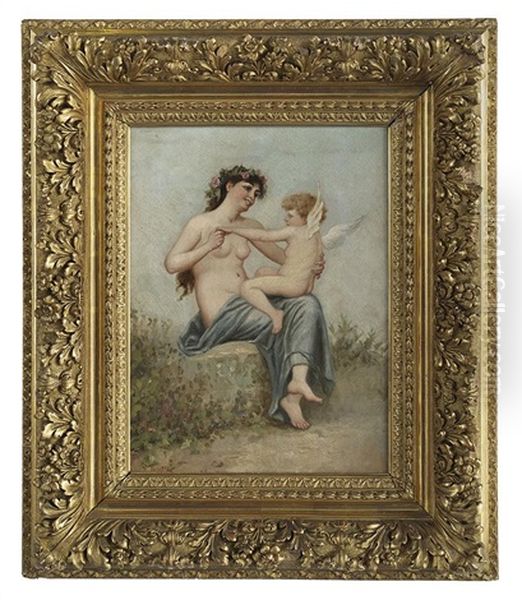

While much of Virgilio Tojetti's fame rested on his large-scale decorative commissions, he also produced easel paintings, including genre scenes, allegorical subjects, and portraits. These smaller works allowed for a different kind of artistic expression, often more intimate and personal.

One such example is the painting titled "Bath Time" (or similar titles depicting bathing scenes). These works typically feature idealized female figures, often nudes or semi-nudes, in classical or vaguely historical settings, such as a Roman bath. The figures are rendered with soft, luminous flesh tones, graceful poses, and a gentle sensuality that recalls the work of Bouguereau and other French academic painters who specialized in the female nude, like Paul-Antoine de la Boulaye or Émile Munier, a student of Bouguereau. These paintings catered to a taste for refined eroticism and classical beauty, and found a ready market among private collectors.

His easel paintings often featured themes popular in the late 19th century: romanticized historical episodes, allegories of love or the seasons, and charming depictions of women and children. The meticulous finish and attention to detail learned from Gérôme would have been evident in these works, making them appealing to patrons who valued technical skill and pleasing subject matter. American artists like Elihu Vedder (1836-1923), though often more symbolic and mystical, also explored classical and allegorical themes in easel paintings during this period.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Techniques

Virgilio Tojetti's artistic style was a harmonious blend of several key influences, primarily rooted in his academic training but adapted to the decorative demands of his commissions.

Academic Classicism: The core of his style was the academic classicism instilled by Gérôme and Bouguereau. This manifested in strong, accurate draftsmanship, a focus on the idealized human form, balanced compositions, and smooth, polished surfaces with imperceptible brushstrokes (the "fini"). His figures, whether mythological deities, historical personages, or frolicking putti, possess a classical grace and anatomical correctness.

Romantic Sensibility: Despite the rigor of his academic training, Tojetti's work often displays a romantic or sentimental quality. This is evident in the gentle expressions of his figures, the idyllic nature of his scenes, and the overall charm and elegance that pervades his art. This aligns with a broader 19th-century taste that tempered strict classicism with more emotive content.

Decorative Flair: Tojetti excelled in decorative painting. He understood how to create compositions that harmonized with architectural spaces, using flowing lines, balanced color palettes, and motifs like floral garlands, ribbons, and architectural elements to create a sense of opulence and visual delight. His work for the Worsham-Rockefeller dressing room is a prime example of his ability to integrate painting into a larger decorative scheme.

Color and Light: His palette was typically rich but refined, employing harmonious color combinations. He was skilled in modeling figures with subtle gradations of light and shadow to create a sense of volume and three-dimensionality, particularly in his rendering of flesh tones, which often have a pearly luminosity.

Influence of the Aesthetic Movement: Working in the Gilded Age, Tojetti was undoubtedly influenced by the principles of the Aesthetic Movement, which emphasized "art for art's sake" and the pursuit of beauty in all aspects of life, including interior decoration. His collaborations with firms like George A. Schastey & Co. place him firmly within this context, where the goal was to create unified, harmonious, and artistically rich environments. This movement also saw artists like James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) championing aesthetic principles, though Whistler's painterly style was quite different from Tojetti's academic finish.

Tojetti's technique typically involved careful preliminary studies and cartoons, especially for large-scale mural projects. For murals, he likely used oil on canvas, which would then be affixed to the wall (marouflage), a common practice that allowed for studio execution and easier installation. His easel paintings would have been executed with traditional oil painting techniques on canvas, built up in layers to achieve the desired smoothness and luminosity.

Collaborations and Professional Network

The nature of decorative art in the Gilded Age often involved extensive collaboration. Virgilio Tojetti's most documented collaboration was with George A. Schastey (c. 1839–1894) and his firm, George A. Schastey & Co. Schastey was a leading cabinetmaker, interior designer, and decorator based in New York, known for his high-quality, artistic furniture and elaborate interior schemes for wealthy clients like the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts.

Their work on the Worsham-Rockefeller house (specifically Arabella Worsham's dressing room) in the early 1880s exemplifies this synergy. Schastey would have designed the overall room, including the paneling, cabinetry, and selection of materials, while Tojetti would have been commissioned to create the painted ceiling and possibly other painted embellishments that integrated seamlessly with Schastey's vision. This partnership highlights the interconnectedness of artists and craftsmen in creating the luxurious interiors of the era.

Beyond Schastey, Tojetti would have worked with architects, other artists, and patrons. Commissions for large hotels like the Ponce de Leon would have involved coordination with the architects (Carrère and Hastings in that case) and other artists working on different aspects of the decoration (like Tiffany for stained glass). His patrons were among the wealthiest and most influential figures in America, and navigating these relationships would have been crucial to his success. He was part of a vibrant artistic community in New York, which included many European-trained artists and American artists who shared a similar academic background.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Virgilio Tojetti continued to work actively throughout the late 19th century. His reputation as a skilled decorative and easel painter remained solid. However, his life was cut short by illness. Virgilio Tojetti died on March 27, 1901, in New York City, at the age of 52. The cause of death was reported as Bright's disease, a historical term for a type of kidney disease (nephritis). His passing was noted in publications like The New York Times, acknowledging him as a well-known artist.

Tojetti's legacy is primarily that of a highly skilled decorative artist who brought European academic traditions to American shores and adapted them to the tastes of the Gilded Age. His work contributed to the richness and opulence of many significant buildings of the era. While the grand decorative schemes he participated in fell out of fashion with the rise of Modernism in the 20th century, there has been a renewed appreciation for the artistry and craftsmanship of the Gilded Age in more recent times.

His easel paintings continue to appear at art auctions, appreciated for their technical skill and charming subject matter. The survival of key works, such as the Worsham-Rockefeller dressing room ceiling at the Museum of the City of New York, allows contemporary audiences to experience the elegance and refinement of his art directly.

Virgilio Tojetti in Art History: Evaluation and Collections

In the broader sweep of art history, Virgilio Tojetti is recognized as a competent and successful practitioner of academic and decorative art. He may not have been an innovator in the vein of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists who were his contemporaries, but he excelled within his chosen idiom. His art perfectly met the demands of his time and patrons, who valued technical polish, classical beauty, and decorative elegance.

Art historical evaluations generally praise his draftsmanship, his graceful compositions, and his ability to create harmonious decorative schemes. Some critics, particularly those with a modernist bias, might have viewed his work (and academic art in general) as overly sentimental or lacking in profound artistic depth. However, a more balanced contemporary perspective acknowledges the historical importance and artistic merit of such work within its own context. He was a key contributor to the visual culture of the Gilded Age in America.

His works are found in several public collections, most notably:

The Museum of the City of New York: Home to the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room ceiling.

The Miraculous Medal Shrine, Philadelphia: Features his religious murals.

His paintings also appear in private collections and occasionally surface in art galleries and auctions. While there are no major ongoing commemorative exhibitions specifically dedicated to Tojetti, his inclusion in broader exhibitions on Gilded Age art or American mural painting would be appropriate. The preservation of his work in situ, where possible, or in museum collections, ensures his contribution to art history is not forgotten. The Boston Public Library was also mentioned as holding some of his work, likely prints or drawings, reflecting the dissemination of artists' imagery.

Conclusion: An Enduring Elegance

Virgilio Tojetti's career represents a fascinating chapter in the story of transatlantic artistic exchange and the development of American visual culture. From his early training in Rome and Paris under the luminaries of French academic art to his successful career as a decorative painter in Gilded Age America, Tojetti consistently demonstrated a high level of technical skill and a refined aesthetic sensibility.

His murals and ceiling paintings transformed the interiors of grand hotels, opulent residences, and sacred spaces into realms of beauty and allegorical significance. Works like the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room ceiling and his contributions to the Ponce de Leon Hotel and the Miraculous Medal Shrine stand as testaments to his talent. While the tastes that celebrated his style of art waned with the advent of modernism, Virgilio Tojetti's paintings continue to be admired for their elegance, craftsmanship, and their evocation of a bygone era of lavish artistry. He remains an important figure for understanding the rich decorative traditions of the late 19th century and the artistic aspirations of Gilded Age America.