Charles Demuth stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of American modern art. Born into the late Victorian era and coming of age during a period of profound artistic transformation, Demuth navigated the currents of European avant-garde movements while forging a distinctly American visual language. He is best known for his central role in the Precisionist movement, his exquisite watercolors, and a series of unique "poster portraits" that captured the essence of his artistic contemporaries. His life, marked by both privilege and persistent physical frailty, informed an art that blended meticulous observation with abstract design, exploring themes ranging from industrial might to the intimate worlds of flowers and hidden social scenes.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Lancaster

Charles Henry Buckius Demuth was born on November 8, 1883, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. His family was well-established and relatively affluent, their wealth derived primarily from the tobacco trade. His father was a partner in a tobacco business, and his mother, Augusta Demuth, eventually took over the family's tobacco shop, a business that had been in her family for generations. This comfortable background provided Demuth with opportunities for education and travel that were crucial to his artistic development.

However, Demuth's childhood was also marked by significant health challenges. At a young age, he suffered from a condition affecting his hip, possibly Perthes disease or tuberculosis of the bone. This left him with a permanent limp and required him to use a cane for much of his life. This physical ailment, coupled with later health issues, contributed to a sense of being an outsider and fostered a close, perhaps dependent, relationship with his mother, with whom he lived for most of his adult life in the family home on East King Street in Lancaster.

Demuth's initial educational path did not point directly towards art. He briefly attended Franklin & Marshall College, also in Lancaster, ostensibly to study law. However, his true interests lay elsewhere, and after only a year, he shifted his focus. He enrolled at the Drexel University of Art, Science and Industry in Philadelphia, where he studied illustration and began honing his skills, particularly in watercolor, a medium in which he would achieve remarkable mastery.

His formal art education continued at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. This was a formative period where he moved beyond illustration into painting. At PAFA, he studied under influential American artists, most notably William Merritt Chase, a leading figure in American Impressionism known for his bravura brushwork and teaching prowess. Thomas Anshutz, another important instructor at PAFA known for his realist approach, also likely influenced Demuth. During his time in Philadelphia, he formed lasting friendships with fellow students, including the poet and physician William Carlos Williams, who would later become the subject of one of Demuth's most famous paintings.

European Sojourns and Avant-Garde Encounters

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Demuth recognized the importance of experiencing European art firsthand. He made several trips abroad, primarily to Paris, which was then the undisputed center of the Western art world. His visits, occurring between 1907 and 1921, were crucial periods of absorption and transformation. He immersed himself in the city's vibrant artistic milieu, studying at institutions like the Académie Colarossi and the Académie Julian.

More importantly, these trips exposed him directly to the radical innovations of the European avant-garde. He encountered Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, absorbing the lessons of artists like Paul Cézanne, whose structured compositions and analysis of form would profoundly impact Demuth's later work. He also witnessed the rise of Fauvism, with its bold, non-naturalistic use of color, exemplified by Henri Matisse. Perhaps most significantly, he experienced the development of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, with its fragmented forms and multiple viewpoints.

In Paris, Demuth moved within expatriate artistic and literary circles. He frequented the salons of Gertrude Stein, a crucial hub for American writers and artists abroad. He developed important friendships and connections, notably with Marsden Hartley, another American modernist painter exploring European styles. Crucially, he also met Marcel Duchamp, the iconoclastic French artist whose conceptual approach and association with Dada would resonate with Demuth's own intellectual inclinations. Through these connections and his direct engagement with modern art, Demuth absorbed the principles that would underpin his mature style.

Demuth did not simply mimic European trends. While deeply influenced by Cubism's geometric analysis and flattened perspectives, he adapted these elements to his own sensibilities and subject matter. He returned to the United States not as a disciple, but as an artist equipped with a new vocabulary to interpret the American scene. His European experiences provided the technical and conceptual tools he needed to forge his unique path within American modernism.

Precisionism: Forging an American Modernist Idiom

Upon returning to the United States, particularly after his final extended trip ending in 1921, Demuth became a central figure in the development of Precisionism. This movement, which flourished primarily in the 1920s and 1930s, is considered one of the first indigenous modern art movements in America. Precisionism is characterized by its sharp focus, clean lines, geometric forms, and often, its celebration of the modern American landscape – particularly industrial structures, skyscrapers, and machinery.

Precisionism drew heavily on the formal language of European Cubism and Futurism but applied it to distinctly American subjects. Unlike their European counterparts, Precisionist artists generally avoided complete abstraction, maintaining a clear connection to recognizable reality. They rendered factories, bridges, grain elevators, and cityscapes with a cool, objective clarity, often imbuing these modern subjects with a sense of monumental grandeur and streamlined beauty. Demuth, along with artists like Charles Sheeler and Georgia O'Keeffe (though her work often transcends easy categorization), became leading exponents of this style.

Demuth's Precisionist works are marked by their meticulous draftsmanship and sophisticated compositions. He often employed intersecting planes of transparent color, derived from Cubism and Orphism (a related movement associated with Robert Delaunay), creating a sense of fractured yet coherent space. These "ray lines," as they are sometimes called, slice across his compositions, adding dynamism and structure without completely dissolving the underlying subject.

His choice of subjects often centered on the architecture of his native Lancaster and the industrial forms that were reshaping the American landscape. He saw beauty and significance in structures that others might overlook, transforming mundane buildings into icons of modernity. This focus on the local and the industrial, rendered with geometric precision and a refined aesthetic sensibility, defined his contribution to Precisionism and secured his place in American art history.

Major Works and Defining Themes

Charles Demuth's oeuvre encompasses a range of subjects and styles, but several key works and thematic concerns stand out, defining his artistic legacy.

Industrial Landscapes and Architectural Studies

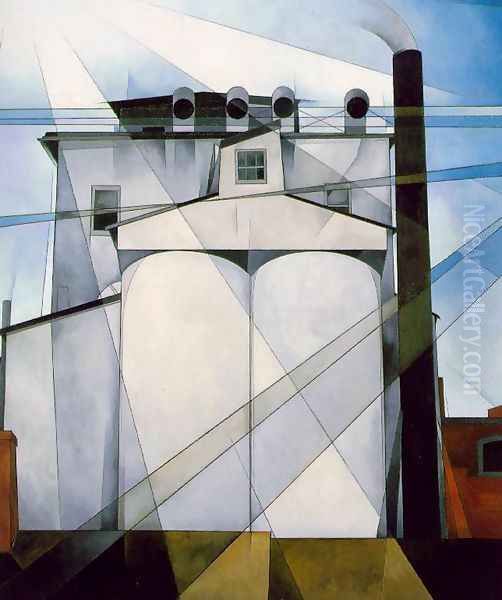

Demuth's fascination with the built environment, particularly the industrial architecture of his time, yielded some of his most powerful Precisionist works. He found compelling subjects in the factories, water towers, and grain elevators of Lancaster and nearby towns. These structures, often seen as symbols of American progress and power, were rendered with a combination of objective clarity and abstract design.

Perhaps the most celebrated of these is My Egypt (1927). The painting depicts massive grain elevators in Lancaster, owned by John W. Eshelman & Sons. Demuth transforms the functional, industrial structure into a monumental icon. The title itself is evocative, suggesting a parallel between the towering forms of American industry and the timeless grandeur of ancient Egyptian pyramids. The composition is dominated by strong vertical and diagonal lines, intersecting planes of subtle color, and a sense of imposing weight and stability. It exemplifies the Precisionist tendency to find classical or even spiritual significance in modern industrial forms.

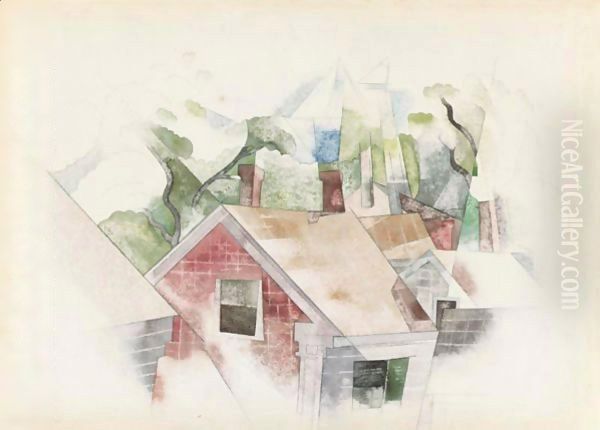

Other works, such as Buildings, Lancaster (1930) and Aucassin and Nicolette (1921), similarly explore architectural themes. Aucassin and Nicolette, despite its medieval literary title, depicts factory chimneys and roofs, again using intersecting planes and geometric simplification to create a dynamic yet ordered composition. Through these works, Demuth captured the changing face of America, finding aesthetic value in the very structures that represented its industrial transformation.

The Iconic Figure 5

Undoubtedly Demuth's most famous single work is I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold (1928). This painting is part of a series of symbolic "poster portraits" Demuth created in the late 1920s, dedicated to his artist and writer friends. This particular work is an homage to his friend, the poet William Carlos Williams, inspired by Williams' poem "The Great Figure." The poem vividly describes the experience of seeing a fire engine speeding through a rainy city street at night.

Demuth's painting brilliantly translates the poem's sensory immediacy into visual form. It features a large, stylized numeral "5" repeated three times in receding scale, suggesting the fire engine's movement towards and past the viewer. The "5" is rendered in gold against a dark, abstracted cityscape composed of geometric shapes representing buildings and streetlights. The words "Bill," "Carlo," and "WCW" are subtly integrated into the composition, referencing Williams. The painting combines elements of advertising signage (the bold numeral), Cubist fragmentation, and Futurist dynamism. It is a masterpiece of Precisionism and is often cited as a precursor to Pop Art, particularly in its use of everyday symbols and commercial aesthetics.

The Poster Portraits

I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold belongs to a unique series Demuth developed, known as poster portraits or symbolic portraits. Instead of depicting his friends' physical likenesses, Demuth created abstract or semi-abstract compositions using objects, symbols, letters, and numbers associated with the person's character, profession, or work. These portraits are witty, intellectually engaging, and highly original contributions to the genre of portraiture.

Besides the portrait of William Carlos Williams, other notable examples include homages to fellow artists Georgia O'Keeffe (using her initials and perhaps floral or natural forms, though interpretations vary), John Marin (evoking his dynamic seascapes), Arthur Dove (perhaps referencing his abstract nature forms), Marsden Hartley (possibly incorporating symbols related to his interests), and the painter Charles Duncan. These works demonstrate Demuth's close connections within the American modernist circle and his innovative approach to representing personality through symbolic means, drawing inspiration from modern advertising and graphic design.

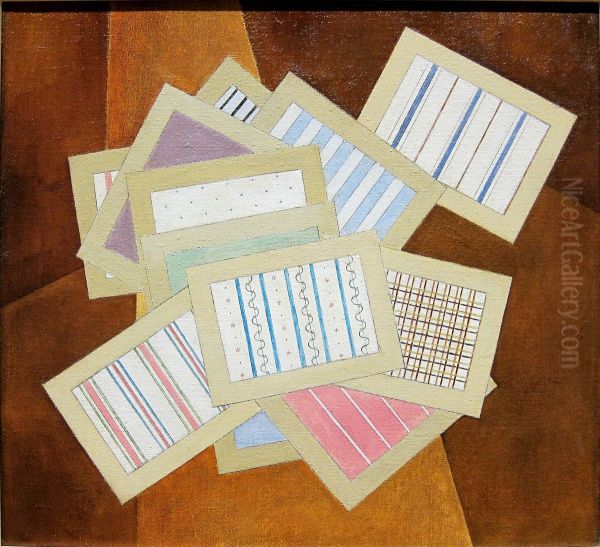

Mastery of Watercolor: Florals, Still Lifes, and Vaudeville

While his Precisionist oils are perhaps better known today, Demuth first gained recognition as a master of watercolor, and he continued to work extensively in this medium throughout his career. His watercolors are characterized by their delicacy, luminosity, and exquisite control. He often used a technique where pencil lines remain visible beneath transparent washes of color, creating a sense of structure and airiness simultaneously.

His subjects in watercolor were diverse. He produced stunning floral studies and still lifes featuring fruits and vegetables. These works, while representational, often push towards abstraction, focusing on the essential forms and colors of the subjects. He applied washes with remarkable precision, allowing the white of the paper to shine through, creating highlights and a sense of brilliance. Some scholars have noted potential influences from Chinese art in the calligraphic quality of his lines and the elegance of his compositions in these still lifes.

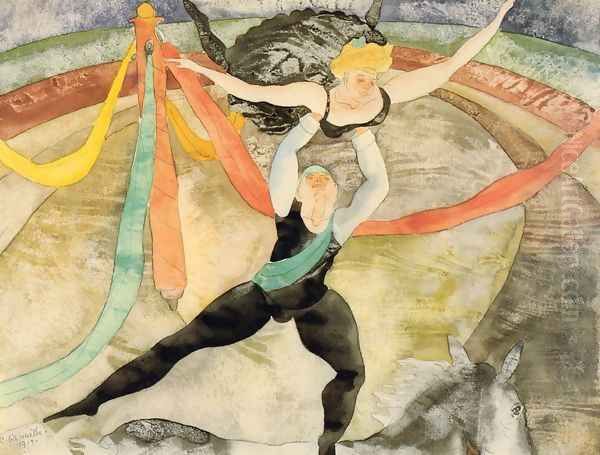

Demuth was also drawn to the world of entertainment, particularly vaudeville, circus performers, and jazz musicians. His watercolors captured the energy and artificiality of the stage, depicting acrobats, clowns, and singers with a fluid, expressive line. These works often possess a nervous energy and a sense of detached observation, reflecting the modern urban experience.

Illustrations and Hidden Worlds

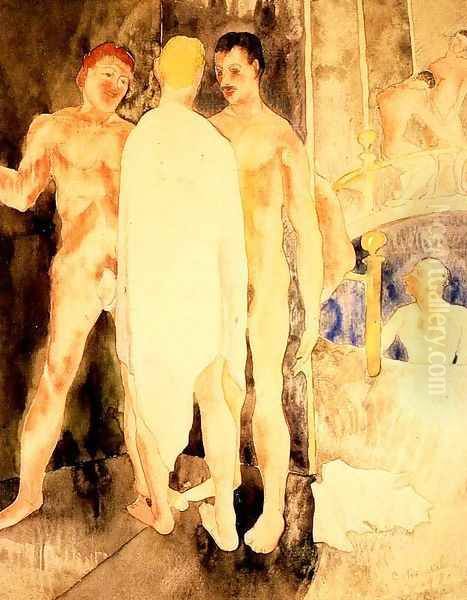

Beyond his paintings, Demuth created a significant body of illustrative work, often for literary texts that explored themes of decadence, psychological complexity, and social critique. He produced illustrations for Émile Zola's novel Nana, Henry James's novella The Turn of the Screw, and Frank Wedekind's plays dealing with sexuality and societal constraints.

These illustrations, primarily in watercolor, are often more explicitly narrative and psychologically charged than his other works. They frequently depict scenes set in cafes, bars, and theaters, sometimes exploring the burgeoning underground gay subculture of cities like New York and Paris. Demuth himself was homosexual, although he lived discreetly, particularly in conservative Lancaster. Some of these illustrations, especially those depicting sailors or scenes in bathhouses, are considered coded explorations of his own identity and the hidden social worlds he navigated. Many of these works were highly personal and not intended for public exhibition during his lifetime, adding another layer to his complex artistic persona.

Artistic Circle, Friendships, and Collaborations

Charles Demuth was part of a vibrant network of American modernists, centered largely around the influential photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz. While Demuth maintained his primary residence in Lancaster, he was deeply connected to the New York art scene. He met Stieglitz, likely through Marcel Duchamp, and became associated with Stieglitz's circle, which included key figures like Georgia O'Keeffe, John Marin, Arthur Dove, and Marsden Hartley.

Stieglitz championed American modernism through his galleries, including the famous 291 gallery, The Intimate Gallery, and An American Place. Demuth exhibited his work at Stieglitz-affiliated venues. For instance, he was included in the significant "Seven Americans" exhibition at the Anderson Galleries in 1925, organized by Stieglitz, which also featured O'Keeffe, Marin, Dove, Hartley, Stieglitz himself, and Paul Strand. This exhibition helped solidify the reputations of these artists as leaders of the American avant-garde.

Demuth maintained close friendships with several members of this circle. His friendship with Georgia O'Keeffe was particularly important. They shared an interest in Precisionist aesthetics, although their styles remained distinct – O'Keeffe often focused on organic forms and Southwestern landscapes, while Demuth concentrated more on architectural and industrial subjects, as well as delicate still lifes. Their mutual respect is evident, and Demuth's poster portrait of O'Keeffe is a testament to their connection.

His long-standing friendship with William Carlos Williams, dating back to their student days in Philadelphia, was also crucial. Their shared interest in capturing the essence of American life – Williams through poetry, Demuth through painting – led to the creation of I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold. Demuth's engagement with literature extended beyond illustration; he collaborated with Williams on symbolic texts, highlighting the cross-pollination between visual art and literature within the modernist movement.

His connection with Marcel Duchamp was also significant. Duchamp's intellectual rigor and questioning of traditional artistic values likely appealed to Demuth. Through these relationships and shared exhibition platforms, Demuth participated actively in the dialogues and developments that shaped American modern art in the early 20th century.

Health Challenges, Later Life, and Death

Charles Demuth's life was persistently shadowed by ill health. His childhood hip condition left him with a lifelong limp. More seriously, in 1920 or 1921, he was diagnosed with diabetes, a condition that was often fatal before the discovery and therapeutic use of insulin. Demuth became one of the first Americans to receive insulin treatment, which undoubtedly prolonged his life but required a strict regimen and constant management.

Despite his frailty, Demuth maintained a productive artistic career for many years. However, the diabetes took a toll, and he suffered from periods of severe illness and exhaustion. Some accounts also mention bouts of nervous collapse and possibly tuberculosis, adding to his physical burdens. Throughout these challenges, he relied heavily on the care of his mother, Augusta, in their Lancaster home, which also served as his studio.

His health significantly impacted his working methods and perhaps his artistic output in later years. Some critics perceive a greater restraint or austerity in his later works, possibly reflecting his physical limitations. The meticulous control required for his watercolors and Precisionist oils demanded considerable energy and focus, which became increasingly difficult to sustain.

Charles Demuth died on October 23, 1935, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, at the relatively young age of 51. The cause of death was complications from diabetes. He died in the house where he had lived for most of his life, cared for by his mother. His death marked the loss of a unique voice in American art, an artist who had successfully synthesized European modernism with a distinctly American sensibility.

Legacy and Influence

Although Charles Demuth achieved recognition within avant-garde circles during his lifetime, particularly through his association with Stieglitz, his broader fame grew significantly after his death. He is now firmly established as a major figure in American modernism and a key pioneer of the Precisionist movement.

His influence can be seen in several areas. His Precisionist paintings, with their clean lines, geometric forms, and focus on industrial subjects, contributed significantly to the development of a modern American aesthetic. Artists like Charles Sheeler continued to explore similar themes, solidifying Precisionism's place in art history.

Demuth's innovative poster portraits, particularly I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, are recognized as groundbreaking works that anticipated later developments in art. Their use of typography, symbols, and elements drawn from commercial culture foreshadowed aspects of Pop Art, which emerged decades later. Artists like Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, who incorporated everyday objects and symbols into their work, can be seen as inheritors of the path Demuth explored. Even Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, while stylistically different, were part of the broader trajectory of American modernism that Demuth helped to shape.

His mastery of watercolor remains highly regarded. His delicate yet structured floral studies and still lifes are considered among the finest examples of American watercolor painting in the 20th century. They demonstrate a unique fusion of careful observation, abstract design, and technical virtuosity.

The Demuth Museum, established in his former home and studio in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, serves as a center for the study and appreciation of his work. It preserves his legacy and provides insight into his life and artistic environment. Through ongoing exhibitions and scholarship, Demuth's contributions continue to be explored and celebrated.

Conclusion

Charles Demuth carved a unique and enduring niche in the history of American art. Emerging from a comfortable but health-challenged background in Lancaster, he absorbed the revolutionary ideas of European modernism during his trips abroad. He skillfully translated these influences – particularly Cubism – into a distinctly American idiom through his central role in the Precisionist movement. His paintings of industrial landscapes, such as My Egypt, transformed mundane structures into icons of modernity, while his masterpiece, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, remains a potent symbol of American dynamism and a precursor to later art movements.

Beyond Precisionism, Demuth excelled as a watercolorist, capturing the delicate beauty of flowers and the vibrant energy of vaudeville with equal finesse. His illustrations and more private works offer glimpses into his complex personality and the hidden social currents of his time. Despite lifelong physical frailty, he produced a body of work characterized by intellectual rigor, aesthetic refinement, and technical brilliance. As an artist who bridged European innovation and American identity, Charles Demuth remains a vital figure, whose meticulous and evocative art continues to resonate.