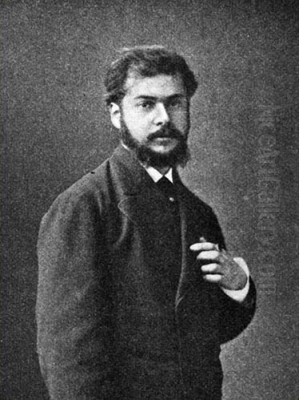

Ernst Abraham Josephson stands as one of Sweden's most compelling and complex artistic figures. Born in Stockholm on April 16, 1851, into a prominent Jewish family deeply involved in the city's cultural life, Josephson's destiny seemed intertwined with the arts from an early age. His life, tragically cut short on November 22, 1906, encompassed periods of brilliant technical mastery, revolutionary artistic leadership, profound personal turmoil, and ultimately, a visionary outpouring that positioned him as a crucial precursor to modern Expressionism. Painter, poet, and a reluctant rebel, Josephson navigated the shifting currents of late 19th-century European art, leaving behind a legacy marked by both luminous realism and haunting, deeply personal visions.

His journey was one of contrasts: between the academic traditions he initially mastered and the modern impulses he later championed; between the celebrated public artist and the tormented individual grappling with mental illness; between the tangible world he depicted with such skill and the spectral realms that dominated his later imagination. Understanding Josephson requires exploring these dualities, recognizing him not just as a Swedish national treasure, but as a significant figure within the broader narrative of European art at a time of profound change.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Josephson's upbringing provided a fertile ground for his burgeoning talents. His family, including his uncle, the composer Jacob Axel Josephson, and his aunt, the theatre figure Ludvig Josephson, fostered an environment rich in music, literature, and visual arts. This cultural immersion undoubtedly shaped his sensibilities. Recognizing his prodigious talent, he enrolled at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm at the young age of sixteen, embarking on a formal artistic education that would provide the technical foundation for his future career.

The Academy, however, represented only the beginning of his artistic education. Like many ambitious artists of his generation, Josephson looked beyond Sweden's borders for inspiration and advanced training. He undertook extensive travels throughout Europe, absorbing the lessons of the Old Masters and engaging with contemporary artistic currents. Italy, Spain, France, and the Netherlands became his classrooms. He spent crucial periods studying in Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world, where he briefly trained under the prominent academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme.

While Gérôme represented the established academic tradition, Josephson's true artistic affinities lay elsewhere. He was profoundly captivated by the works of the Dutch Golden Age master, Rembrandt van Rijn. Rembrandt's dramatic use of chiaroscuro, his psychological depth in portraiture, and his textural richness resonated deeply with Josephson, becoming a recurring touchstone throughout his career. Similarly, the Spanish master Diego Velázquez, particularly his directness and painterly realism, left a significant mark, evident in Josephson's later works inspired by his travels in Spain. He also absorbed the lessons of French Realists like Gustave Courbet and the burgeoning modernity of Édouard Manet.

The Realist Master: Early Career and Acclaim

Returning to Sweden and working between Stockholm and Paris, Josephson quickly established himself as a painter of exceptional technical skill and psychological insight. His early career is characterized by a powerful, often dark-toned realism, heavily indebted to Rembrandt and the Baroque tradition, yet infused with a distinctly modern sensibility. He excelled in portraiture, capturing not just the likeness but the inner life of his sitters with remarkable acuity. His portraits of friends, family, and prominent figures are noted for their strong presence, sophisticated handling of paint, and nuanced exploration of character.

One of his most significant early works is the monumental David and Saul (1878). This ambitious history painting, depicting the biblical scene of the young David soothing the troubled King Saul with his harp, showcases Josephson's mastery of composition, dramatic lighting, and historical detail. While rooted in academic tradition, the painting possesses a psychological intensity and emotional weight that foreshadows his later concerns. It demonstrated his ability to tackle grand themes with technical brilliance, aiming for recognition within the established Salon system.

During the early 1880s, Josephson's travels to Spain yielded another masterpiece, Spanish Blacksmiths (c. 1881-1882). This work vividly captures a scene of working-class life, depicting figures in a forge with a raw energy and realism reminiscent of Velázquez and Courbet. The painting is celebrated for its bold brushwork, its convincing portrayal of light and heat, and its unsentimental depiction of labour. It solidified his reputation as a leading figure among the younger generation of Swedish realists, capable of infusing everyday scenes with monumental power. His genre scenes often depicted Swedish folk life, contributing to the growing interest in national themes.

The Opponents: Challenging the Establishment

Despite his growing success within conventional parameters, Josephson became increasingly dissatisfied with the conservative atmosphere of the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. He felt its teaching methods were outdated and stifling, failing to engage with the progressive artistic ideas emerging from France, particularly Impressionism and plein-air painting. Josephson was not alone in his critique; a growing number of young Swedish artists shared his frustration.

In 1885, this discontent coalesced into a formal movement known as "Opponenterna" (The Opponents). Josephson emerged as one of the movement's most articulate and passionate leaders. The Opponents drafted a petition demanding reforms to the Academy's structure and curriculum, advocating for modernization and greater artistic freedom. The group included many artists who would become central figures in Swedish art, such as Anders Zorn, Carl Larsson, Karl Nordström, Richard Bergh, Nils Kreuger, Bruno Liljefors, and Eugène Jansson.

The Academy establishment rejected the Opponents' demands, leading to a definitive break. In 1886, the Opponents formed their own association, the "Konstnärsförbundet" (The Artists' Association), which organized independent exhibitions and effectively created an alternative to the official Salon. Josephson played a crucial role in this organization, serving as its chairman for a period. This act of rebellion was pivotal in Swedish art history, challenging the hegemony of the Academy and paving the way for the acceptance of modern art forms in Sweden. Josephson's leadership cemented his position as a forward-thinking artist committed to artistic renewal.

National Romanticism and The Water Sprite

Concurrent with his leadership in the Opponents movement, Josephson's art began to explore themes rooted in Swedish folklore and mythology, aligning with the broader National Romantic movement sweeping across Scandinavia. This period saw the creation of one of his most iconic and controversial works, Strömkarlen (The Water Sprite or The Nix), painted between 1882 and 1884. The painting depicts a naked, muscular male figure playing a violin amidst a rushing waterfall – the personification of the powerful, often dangerous spirit of the waters from Nordic folklore.

Strömkarlen is a powerful synthesis of realism in the depiction of the figure and the landscape, combined with a deeply symbolic and mythological subject matter. The raw energy of the water and the intense focus of the Nix create a mesmerizing, slightly unsettling image. Josephson submitted the painting to the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, but it was controversially rejected by the museum board, likely due to its perceived crudeness or unconventional subject matter.

The rejection caused a public outcry and became a rallying point for the Opponents and their supporters. The controversy highlighted the clash between the conservative art establishment and the emerging modern artistic sensibilities. Fortunately, the painting found an appreciative home. Prince Eugen, himself an accomplished painter and a crucial patron of the Konstnärsförbundet artists, purchased Strömkarlen for his personal collection (now housed at Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde museum). The incident underscored Josephson's willingness to tackle challenging national themes and push artistic boundaries, even at the risk of official disapproval.

The Turning Point: Illness and Artistic Transformation

The late 1880s marked a dramatic and tragic turning point in Josephson's life and art. While staying on the Île-de-Bréhat off the coast of Brittany in the summer of 1888, Josephson experienced a severe mental breakdown. He began suffering from delusions and paranoia, believing himself to be possessed by the spirits of dead masters, particularly Rembrandt and Velázquez. He engaged in spiritualist practices and his behaviour became increasingly erratic. This period of intense psychological distress necessitated his return to Sweden and subsequent hospitalization.

The exact nature of Josephson's illness remains a subject of discussion among historians, with diagnoses ranging from schizophrenia to complications arising from syphilis, which he had reportedly contracted in his youth. Regardless of the precise medical definition, the impact on his art was profound and transformative. The polished realism and controlled technique of his earlier years gave way to a radically different style, characterized by visionary intensity, distorted forms, and a raw, expressive energy.

His illness did not entirely halt his artistic production; instead, it redirected it. Confined for periods, he continued to draw and paint prolifically, often on unconventional materials like scraps of paper or notebook covers. These later works, created during periods of intense mental turmoil but also moments of lucidity, are among the most fascinating and challenging in his oeuvre. They offer a direct, unfiltered glimpse into his inner world, a realm populated by mythological figures, spiritual visions, and reimagined portraits imbued with an almost hallucinatory quality.

The Visionary Works: Art from the Depths

The art Josephson produced after 1888 stands apart from his earlier work and, indeed, from much of the art being produced by his contemporaries. While artists like Edvard Munch in Norway were exploring psychological themes with groundbreaking intensity, Josephson's post-illness work possessed a unique character, born directly from his altered state of consciousness. He often signed these works with the names of the masters he believed were guiding his hand, such as Rembrandt.

These later drawings and paintings are characterized by rapid, gestural lines, bold simplifications of form, and a disregard for conventional perspective and anatomy. Figures might be elongated or compressed, features exaggerated, and compositions charged with a dynamic, sometimes chaotic energy. Subjects often drew from mythology, biblical stories, or Swedish folklore, but reinterpreted through the lens of his personal visions and struggles. Portraits from this period often transform the sitter into archetypal figures or spectral presences.

While some dismissed these works as products of a diseased mind, others recognized their extraordinary power and originality. They possess an emotional immediacy and expressive force that anticipates the development of Expressionism in the early 20th century. Artists and critics began to see in Josephson's late work a profound exploration of the subconscious and a radical break from naturalistic representation. Though created in isolation and under duress, these works would later be hailed for their visionary quality and their influence on subsequent generations of modern artists. His use of line became paramount, conveying emotion and form with startling directness.

Poetry and Multifaceted Talent

Josephson's creativity was not confined to the visual arts. He was also a gifted poet, and his literary output provides another crucial dimension to understanding his artistic personality. He published two collections of poetry: Svarta rosor (Black Roses, 1888) and Gula rosor (Yellow Roses, 1896). These poems often mirror the themes and moods found in his paintings, exploring love, loss, nature, mythology, and the inner turmoil of the human spirit.

Svarta rosor, published shortly before his major breakdown, is particularly notable for its passionate, sometimes dark and melancholic tone, reflecting the emotional intensity that characterized his life. The poems are written in a rich, evocative language, demonstrating a lyrical sensibility that complements his visual artistry. There is often a strong interplay between his poems and his paintings; themes and images cross-pollinate, suggesting a unified creative vision expressed through different media. His multifaceted talents, encompassing painting, drawing, and poetry (and an interest in music), mark him as a true Renaissance man of his time, albeit one wrestling with profound personal challenges.

His writings, like his later artworks, offer insights into his complex psyche and his engagement with the Symbolist currents that emphasized subjective experience, dreams, and the mystical. The combination of his visual and literary work provides a richer, more complete picture of an artist grappling with the fundamental questions of existence, identity, and the nature of creativity itself.

Legacy and Influence

Ernst Josephson's legacy is multifaceted. In Sweden, he is revered as one of the nation's most important painters, a key figure who bridged the gap between 19th-century realism and 20th-century modernism. His leadership in the Opponenterna movement was instrumental in liberalizing the Swedish art world and introducing progressive European ideas. His early realistic works, such as David and Saul and Spanish Blacksmiths, remain masterpieces of the period, demonstrating his exceptional technical prowess and psychological depth. Works like Strömkarlen are cornerstones of Swedish National Romanticism.

Beyond Sweden, Josephson's influence, particularly that of his later, visionary work, has been increasingly recognized. Although created during a period of illness and relative isolation, these drawings and paintings, with their expressive intensity and formal experimentation, anticipated key aspects of Expressionism. Artists like Edvard Munch, though developing his own unique path, shared Josephson's interest in exploring the depths of human psychology through art.

In the early 20th century, as interest in 'outsider art' and the art of the mentally ill grew, Josephson's later work gained new appreciation. Exhibitions in Stockholm and later internationally brought his visionary drawings to a wider audience. There is evidence that major figures of modern art, including Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani, encountered and were intrigued by Josephson's work. His raw energy, his willingness to distort form for emotional effect, and his direct engagement with the subconscious resonated with the burgeoning modernist spirit. He influenced subsequent generations of Swedish modernists, including figures like Isaac Grünewald.

Josephson's life story, marked by both brilliant achievement and profound suffering, adds another layer to his legacy. He embodies the archetype of the tormented genius, an artist whose personal struggles fueled a unique and powerful creative vision. His journey from celebrated realist painter to visionary outsider artist continues to fascinate art historians and the public alike.

Conclusion: An Enduring Presence

Ernst Josephson remains an enduring and vital presence in the history of art. His career trajectory, from a technically brilliant realist and leader of artistic reform to a visionary explorer of the inner psyche, encapsulates the dramatic shifts occurring in European culture at the turn of the century. He mastered the traditions of the past, drawing inspiration from Rembrandt and Velázquez, while simultaneously challenging the academic establishment alongside contemporaries like Zorn and Larsson, pushing Swedish art towards modernity.

His later works, born from a period of profound mental anguish, stand as a testament to the resilience of the creative spirit and offer a startlingly modern exploration of subjective experience. They secure his place not only as a giant of Swedish painting but also as a significant precursor to the Expressionist movements that would define the early 20th century. Ernst Josephson's art, in both its luminous realism and its visionary intensity, continues to speak to us today, reminding us of the complex interplay between technical skill, emotional depth, personal struggle, and artistic innovation. His life and work remain a compelling study in the power and fragility of genius.