Käthe Kollwitz stands as one of the most powerful and poignant artists of the 20th century. A German painter, printmaker, and sculptor, her work transcended aesthetic concerns to delve deep into the human condition, chronicling the hardships, sorrows, and resilience of ordinary people, particularly the working class and those affected by conflict. Operating largely outside the main avant-garde movements yet undeniably modern, Kollwitz forged a unique path, using her art as a tool for social commentary and an expression of profound empathy. Her legacy is built not only on her technical mastery, especially in the graphic arts, but also on the enduring moral weight and emotional honesty of her creations.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

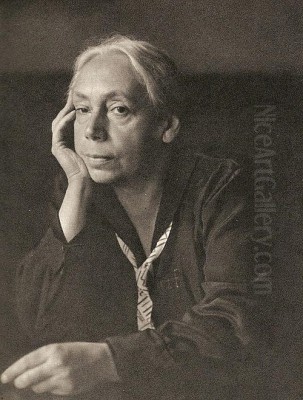

Käthe Kollwitz was born Käthe Schmidt on July 8, 1867, in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia). Her upbringing was formative, steeped in intellectual and social consciousness. Her father, Karl Schmidt, was a master mason who later became a social democratic preacher, and her maternal grandfather, Julius Rupp, was a pastor expelled from the official state church for his liberal theology. This environment fostered independent thought and a sensitivity to social justice issues from a young age. Recognizing her talent, her father encouraged her artistic pursuits, arranging for her first drawing lessons at the age of twelve.

Formal art training for women was limited at the time, but Kollwitz persevered. She studied at an art school for women in Berlin from 1884 to 1885 under Karl Stauffer-Bern, a friend of the symbolist artist Max Klinger. Klinger's work, particularly his socially critical print cycles, would become a significant influence on Kollwitz's decision to focus on graphic arts. She continued her studies in Munich from 1888 to 1889, where she encountered the naturalistic trends prevalent in German art, perhaps absorbing influences from the realism of artists like Wilhelm Leibl, although her path would lead towards greater expression.

During her studies, she became engaged to Karl Kollwitz, a medical student who shared her socialist ideals. Her family background, combined with her education and exposure to influential artists like Klinger, laid the groundwork for an artistic career dedicated to depicting the realities of human struggle with unflinching honesty and deep compassion. The seeds of her later focus on themes of poverty, suffering, and maternal strength were sown in these early years.

Marriage, Motherhood, and a Defining Move

In 1891, Käthe Schmidt married Dr. Karl Kollwitz. The couple moved to Berlin, settling in the working-class district of Prenzlauer Berg. Karl opened a medical practice there, primarily serving the poor factory workers and their families. This move was pivotal for Käthe Kollwitz's artistic development. Daily life immersed her in the harsh realities faced by the urban proletariat – poverty, illness, inadequate housing, and the constant struggle for survival. Her husband's patients became her subjects, not as detached observations, but as individuals whose lives resonated with her own burgeoning social conscience.

The early years of her marriage also saw the birth of her two sons, Hans in 1892 and Peter in 1896. The experience of motherhood profoundly impacted her art, adding layers of intimacy, protectiveness, and vulnerability to her work. She explored the intense bond between mother and child, themes of maternal anxiety, and the fierce instinct to shield offspring from harm. This personal experience intertwined with her social observations, allowing her to depict the suffering of women and children with particular empathy.

Balancing the demands of being a wife, mother, and artist in this environment was challenging, yet it fueled her creativity. Inspired by Max Klinger's print cycles, she began to focus seriously on printmaking – etching, lithography, and later woodcut – finding these mediums ideal for their directness, reproducibility, and capacity for strong tonal contrasts suitable for her often somber themes. Her proximity to the working class provided endless subject matter, transforming her art from academic exercises into powerful social documents.

Breakthrough: The Weavers' Revolt

Kollwitz achieved her first major artistic breakthrough with the print cycle Ein Weberaufstand (A Weavers' Revolt), created between 1893 and 1897. This series of six works (three lithographs, three etchings) was inspired by Gerhart Hauptmann's naturalist play Die Weber (The Weavers), which dramatized the doomed 1844 uprising of Silesian weavers protesting starvation wages and exploitative conditions. Kollwitz did not merely illustrate the historical event; she used it as a vehicle to explore timeless themes of oppression, poverty, and the desperate struggle for dignity.

The cycle unfolds with stark realism and growing emotional intensity. It begins with scenes depicting the weavers' misery ("Not" - Poverty) and the death of a child ("Tod" - Death), moves through deliberation ("Beratung" - Conspiracy) and the march on the factory owner's house ("Sturm" - Attack), culminating in the violent suppression of the revolt ("Ende" - The End). Kollwitz focused on the human cost of the conflict, emphasizing the suffering and determination of the weavers rather than glorifying violence. Her figures are gaunt, weary, yet imbued with a powerful sense of collective will.

When exhibited in 1898 at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition, A Weavers' Revolt caused a sensation. The jury proposed awarding Kollwitz a gold medal, but Kaiser Wilhelm II, offended by the work's raw depiction of social unrest, vetoed the honor. This incident, however, only served to increase Kollwitz's fame and solidify her reputation as a courageous artist willing to tackle difficult social truths. The series marked her arrival as a major force in German art and established the thematic territory she would explore throughout her career, drawing comparisons to earlier social critics in art like Honoré Daumier.

The Peasant War Cycle

Following the success of A Weavers' Revolt, Kollwitz embarked on another ambitious print cycle, Bauernkrieg (Peasant War), produced between 1902 and 1908. This series of seven etchings drew inspiration from Wilhelm Zimmermann's historical account of the German Peasants' War of 1524–1525, a widespread popular revolt in German-speaking areas of Central Europe against the aristocracy and clergy. As with the weavers' uprising, Kollwitz used this historical event to explore broader themes of social injustice, revolution, and the suffering endured by the oppressed.

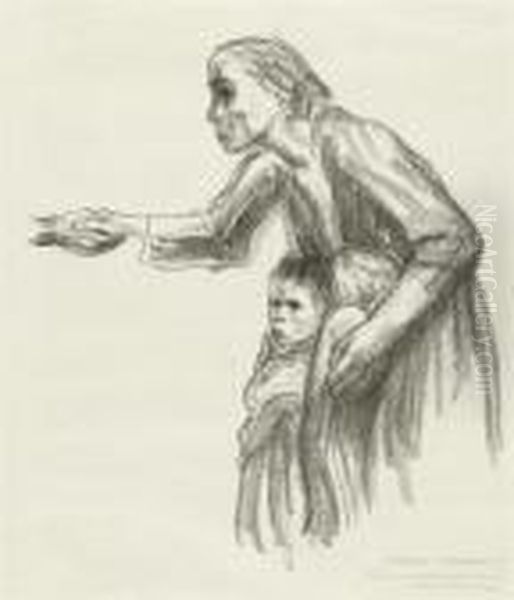

The Peasant War cycle demonstrates a development in Kollwitz's style, moving towards even greater expressive power and formal condensation. Works like "Die Pflüger" (The Plowmen) depict the back-breaking labor and simmering resentment of the peasants. "Vergewaltigt" (Woman Assaulted) conveys the brutal violation experienced by the vulnerable. The iconic central image, "Losbruch" (Outbreak), captures the explosive energy of the revolt, led by the figure of Black Anna, a historical figure Kollwitz transforms into an archetypal symbol of righteous fury and maternal strength urging the peasants forward.

Other plates, such as "Bewaffnung in einem Gewölbe" (Arming in a Vault) and "Schlachtfeld" (Battlefield), depict the preparation for conflict and its horrific aftermath, focusing on a mother searching for her son among the dead. The cycle concludes not with victory, but with the haunting image of captured peasants in "Die Gefangenen" (The Prisoners). Throughout the series, Kollwitz masterfully uses etching techniques, employing dense networks of lines and dramatic chiaroscuro to heighten the emotional impact. The Peasant War cycle further cemented her reputation and showcased her ability to imbue historical subjects with contemporary relevance and profound human feeling.

The Shadow of War: Personal Loss and Artistic Response

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought profound personal tragedy to Käthe Kollwitz and irrevocably shifted her artistic focus. Like many Germans, she initially experienced a wave of patriotism. Her younger son, Peter, barely eighteen, volunteered for the army with his mother's reluctant consent. Tragically, Peter was killed in action in Flanders, Belgium, just weeks after the war began, in October 1914. This devastating loss plunged Kollwitz into deep grief and transformed her understanding of war. Any lingering patriotic sentiment was replaced by a profound sense of sorrow and a commitment to pacifism.

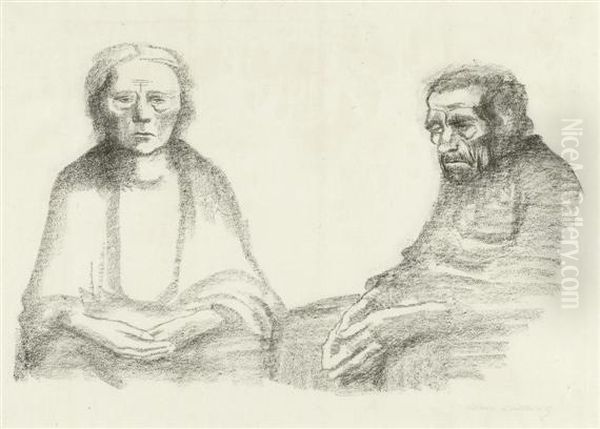

The experience of losing her son became a central theme in her subsequent work. She began planning a memorial sculpture to Peter and his fallen comrades almost immediately, a project that would take nearly two decades to complete: Die trauernden Eltern (The Grieving Parents). This powerful work, eventually carved in granite and placed in the Vladslo German war cemetery in Belgium where Peter is buried, depicts two figures – representing Karl and Käthe herself – kneeling in perpetual mourning. It is a deeply personal yet universal statement about parental grief and the human cost of war.

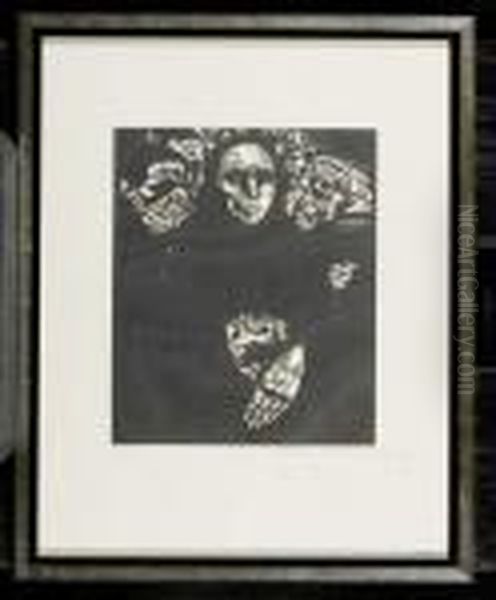

During and after the war, Kollwitz produced numerous works reflecting its impact. The woodcut cycle Krieg (War), created between 1921 and 1922, is perhaps her most famous response. Using the stark, expressive potential of the woodcut medium, she depicted the suffering caused by the conflict, focusing not on battles but on the experiences of those left behind: the grieving mothers ("Die Mütter"), the starving children ("Die Witwe I" - The Widow I), and the sacrifices demanded ("Das Opfer" - The Sacrifice). Her work stood in stark contrast to any glorification of conflict, aligning her more with artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz who also depicted the war's brutality, though often with more overt satire or grotesqueness than Kollwitz's somber empathy.

Weimar Recognition and Social Engagement

The period of the Weimar Republic (1919-1933) brought Käthe Kollwitz significant public recognition and opportunities, even as Germany grappled with post-war turmoil, economic hardship, and political instability. In 1919, she was elected as the first female member of the prestigious Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin. The following year, she was granted full professorship and appointed head of the Master Studio for Graphic Arts at the Academy. This was a landmark achievement for a woman artist in Germany at the time.

Throughout the Weimar years, Kollwitz remained deeply engaged with social issues. She lent her artistic talents to causes she believed in, creating powerful posters advocating for international workers' aid, protesting against anti-abortion laws, and famously, calling for peace with the iconic lithograph "Nie Wieder Krieg!" (Never Again War!) in 1924. Her art became synonymous with humanitarian concerns and the plight of the underprivileged. Her diaries and letters from this period reveal her ongoing commitment to social justice, though she maintained her independence, never formally joining a political party, identifying primarily as a socialist in a broader, humanist sense.

In 1929, she received one of the highest civilian honors of the Weimar Republic, the Order Pour le Mérite for Arts and Sciences. Her work was widely exhibited and collected, both in Germany and internationally. She traveled to Moscow in 1927, observing the results of the Russian Revolution, though her diaries express a complex mix of hope and skepticism. Despite her growing fame, her art never lost its focus on the fundamental struggles of human existence, often depicting themes of hunger, poverty, and the enduring strength of women, particularly mothers. Her expressive style resonated with the emotional intensity found in the work of fellow artists like the sculptor Ernst Barlach.

Artistic Style and Technical Mastery

Käthe Kollwitz's artistic style is characterized by its emotional intensity, its focus on the human figure, and its masterful use of graphic media. While often associated with German Expressionism due to the raw emotion and social concerns in her work, she never formally belonged to Expressionist groups like Die Brücke (The Bridge), whose members included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, or Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), associated with Wassily Kandinsky. Kollwitz developed her own distinct visual language, rooted in 19th-century realism and symbolism but charged with a modern psychological depth and expressive force.

Her primary mediums were drawing and printmaking. She excelled in etching, using intricate lines and deep biting to create rich textures and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, particularly evident in the Peasant War cycle. She was also a master of lithography, exploiting its potential for subtle tonal gradations and powerful black forms, often used for posters and later works like the Death cycle. After WWI, she increasingly turned to woodcut, embracing its capacity for stark, simplified forms and bold contrasts, which suited the monumental grief expressed in the War cycle.

Central to her work is the human figure, often depicted with anatomical accuracy yet imbued with profound emotion. She frequently focused on the hands and faces, conveying suffering, determination, or tenderness through gesture and expression. Women, particularly mothers, are recurring subjects – protective, grieving, enduring, resisting. Her numerous self-portraits, created throughout her life, serve as a remarkable record of her own aging process and inner life, reflecting personal sorrows and the weight of the times. Unlike some contemporaries, her art rarely strayed into pure abstraction; its power derived from its connection to lived human experience, a quality shared perhaps with artists like Paula Modersohn-Becker, another significant German woman artist focused on female subjects.

The Nazi Era: Persecution and Resilience

The rise of the Nazi Party to power in 1933 marked a dark turn for Käthe Kollwitz. Her art, with its focus on suffering, social critique, and pacifism, was antithetical to the Nazi ideology of strength, racial purity, and militarism. Along with many other modern artists like Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde, and her friend Ernst Barlach, her work was deemed "Entartete Kunst" (Degenerate Art).

Shortly after Hitler became Chancellor, Kollwitz and writer Heinrich Mann were forced to resign from the Prussian Academy of Arts after signing an urgent appeal urging the Social Democratic and Communist parties to unite against the Nazis in the upcoming election. Although she was not arrested, she faced increasing persecution. Her works were removed from museums and public collections, and she was effectively banned from exhibiting. The Gestapo visited her home, threatening her and her husband with deportation to a concentration camp, though this threat was ultimately not carried out, possibly due to her international reputation.

Despite the oppressive atmosphere and personal danger, Kollwitz continued to work privately. During this period, from 1934 to 1937, she created her final major print cycle, Tod (Death). This series of eight lithographs explores the theme of death not as a social catastrophe like war, but as an elemental force, approaching individuals with grim intimacy – a mother, an old woman, children. It is a somber, deeply personal meditation on mortality, created under the shadow of tyranny and personal hardship. Her husband, Karl, died in 1940. She also completed her poignant sculpture Mutter mit totem Sohn (Mother with Dead Son), a variation on the Pietà theme, which serves as a powerful lament.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

The final years of Käthe Kollwitz's life were marked by further loss and displacement due to World War II. In 1943, her Berlin home and studio were destroyed in an Allied bombing raid, resulting in the loss of many drawings, prints, and printing plates. Already frail and grieving the recent death of her husband and the earlier loss of her grandson Peter (named after her son) on the Russian front in 1942, she was forced to evacuate Berlin.

She first moved to Nordhausen, and then, in July 1943, accepted an invitation from Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony to live as his guest in Moritzburg, a town near Dresden. She spent the last two years of her life there, physically weak but mentally alert, continuing to draw when her strength allowed. Käthe Kollwitz died in Moritzburg on April 22, 1945, just sixteen days before the end of World War II in Europe.

Her death marked the end of a life dedicated to bearing witness to the human condition through art. In the post-war era, her reputation grew immensely, both in Germany and internationally. Her work was seen as embodying the conscience of Germany, confronting the traumas of war and social injustice with profound empathy. Museums dedicated to her work were established in Cologne and Berlin. Her sculpture Mother with Dead Son was enlarged and placed in the Neue Wache in Berlin, Germany's central memorial for the victims of war and tyranny.

Käthe Kollwitz's legacy endures. She remains a pivotal figure in 20th-century art, admired for her technical skill, her emotional honesty, and her unwavering commitment to social justice. Her powerful depictions of suffering, grief, and resilience continue to resonate, reminding viewers of the human cost of conflict and inequality. Her work stands alongside that of artists like Francisco Goya, who centuries earlier used printmaking to expose the horrors of war, securing her place as one of history's most significant artists of social conscience.

Conclusion: An Art of Empathy

Käthe Kollwitz carved a unique and enduring path in the landscape of modern art. As a woman in a male-dominated field, she achieved remarkable success and influence, becoming the first female professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts. More importantly, she harnessed her considerable artistic talents – particularly in the demanding mediums of etching, lithography, and woodcut – to serve a profound moral purpose. Her work consistently gave voice to the voiceless, depicting the struggles of the working class, the sorrows of mothers, the devastation of war, and the universal confrontation with death. While informed by the artistic currents of her time, from Realism to Expressionism, her style remained deeply personal, characterized by its emotional weight and compassionate gaze. Facing personal tragedy and political persecution, she never wavered in her commitment to an art rooted in human experience and social responsibility. Käthe Kollwitz's legacy is not just one of artistic achievement, but of profound empathy rendered visible, a timeless testament to the power of art to bear witness and advocate for humanity.