Ernst Oppler stands as a significant, if sometimes understated, figure in the landscape of German art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter and etcher of considerable skill, he navigated the currents of Impressionism, the dynamism of the Berlin Secession, and the ephemeral world of dance, leaving behind a body of work that captures the spirit of his era. His art, characterized by a delicate touch and a keen observational eye, offers insights into the cultural life of Germany, particularly Berlin, during a period of profound artistic transformation.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

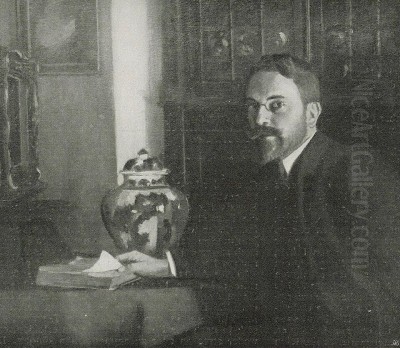

Born on September 19, 1867, in Hanover, Ernst Oppler was immersed in an environment where art and design were highly valued. His father, Edward Oppler, was a prominent German-Jewish architect, known for his work on synagogues and other significant buildings. This familial background likely instilled in young Ernst an early appreciation for form, structure, and aesthetic expression, even though his own path would lead him primarily to the canvas and the etching plate rather than architectural blueprints.

Oppler's formal artistic training began at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, a major center for artistic education in Germany at the time. Here, he would have been exposed to the prevailing academic traditions, but also to the burgeoning new ideas that were challenging them. One of his influential teachers was Nikolaos Gysis, a Greek painter who was a leading figure of the Munich School, known for his genre paintings and historical subjects. Under such tutelage, Oppler would have honed his technical skills in drawing and painting, laying a solid foundation for his future explorations.

Munich, during Oppler's formative years, was a crucible of artistic debate. The traditional, often narrative-driven, historical painting was still dominant in academic circles, but the winds of change were blowing from France, carrying with them the revolutionary concepts of Impressionism. Artists like Fritz von Uhde were already beginning to incorporate Impressionistic light and color into their work, signaling a shift in German artistic sensibilities.

Broadening Horizons: London, the Netherlands, and Paris

To further his artistic development, Oppler, like many aspiring artists of his generation, embarked on travels that exposed him to a wider range of influences. He spent time in London, where he would have encountered the work of artists such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Whistler's emphasis on "art for art's sake," his subtle tonal harmonies, and his often atmospheric depictions of urban life and portraits, may have resonated with Oppler's own developing aesthetic. The London art scene, with its mix of Pre-Raphaelite romanticism and emerging modern trends, offered a different perspective from the more conservative German academies.

His travels also took him to the Netherlands. Dutch art, particularly the legacy of the 17th-century Golden Age masters like Rembrandt van Rijn and Johannes Vermeer, had long been a source of inspiration for artists. The Dutch command of light and shadow, their intimate genre scenes, and their realistic portrayal of everyday life could have provided valuable lessons. Furthermore, the contemporary Hague School, with artists like Jozef Israëls and Anton Mauve, was known for its atmospheric landscapes and depictions of rural life, often rendered with a muted palette that captured the specific light of the Dutch coast and countryside. This engagement with Dutch art, both historical and contemporary, likely enriched Oppler's understanding of light, atmosphere, and composition.

A crucial period of study and work was spent in France, the birthplace of Impressionism. While it's not explicitly detailed which French Impressionists he directly studied under, his time there undoubtedly exposed him to the full force of the movement. The works of Claude Monet, with his series paintings capturing fleeting moments of light and color; Edgar Degas, with his innovative compositions and focus on dancers and modern life; Camille Pissarro, with his depictions of rural and urban landscapes; and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, with his vibrant figures and scenes of leisure, would have been unavoidable. The Impressionist emphasis on capturing the subjective visual sensation, the use of broken brushwork, and the depiction of contemporary life were radical departures from academic tradition and profoundly shaped the course of modern art. Oppler absorbed these influences, adapting them to his own artistic temperament.

Berlin and the Secession: A Voice for Modernism

Ultimately, Ernst Oppler settled in Berlin, which by the late 19th and early 20th centuries was rapidly becoming a major cultural and artistic hub in Europe. It was here that he became a prominent and active member of the Berlin Secession, an art association founded in 1898. The Secession movement, which also had iterations in Munich and Vienna, represented a break from the established, conservative art institutions, such as the Association of Berlin Artists and the state-run Prussian Academy of Arts, which largely controlled official exhibitions and artistic patronage.

The Berlin Secession, under the leadership of figures like Max Liebermann, championed artistic freedom and provided a platform for more progressive, modern styles, particularly Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Liebermann, along with Lovis Corinth and Max Slevogt, formed the "triumvirate" of German Impressionism, and Oppler found himself in esteemed company. Other notable members of the Berlin Secession included Walter Leistikow, known for his melancholic Brandenburg landscapes, and Lesser Ury, who also captured the urban atmosphere of Berlin with an Impressionistic sensibility.

Within this dynamic group, Oppler contributed to the advocacy for what was then considered "new art." The Secessionists organized their own exhibitions, which were critical in introducing the German public to modern artistic trends from both Germany and abroad. Oppler's involvement signifies his commitment to these new artistic ideals and his role in shaping the German art scene. His work from this period reflects the Impressionist concern with light, color, and capturing the fleeting moment, applied to a variety of subjects.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Ernst Oppler's artistic style is best characterized as German Impressionism, though it also subtly incorporates elements that might hint at a lingering Romantic sensibility or a classical appreciation for form. He was less radical in his dissolution of form than some of his French counterparts, often maintaining a clearer delineation of figures and objects, yet his work is undeniably infused with the Impressionist spirit.

His paintings often feature a bright palette and a concern for the effects of light, whether it's sunlight dappling through trees in a park, the soft glow of interior lamps, or the vibrant illumination of a stage. His brushwork could be fluid and expressive, capturing the texture of fabric, the shimmer of water, or the energy of a bustling scene.

Oppler's thematic range was diverse. He painted portraits, often of society figures, rendered with a sensitivity that captured not just a likeness but also a sense of personality. His interior scenes are intimate and evocative, depicting quiet moments in domestic settings, often with a focus on the interplay of light and shadow within the room. He also painted landscapes and cityscapes, capturing the atmosphere of beaches, parks, and urban environments. The Beach of Utrecht, for example, showcases his ability to render the expansive quality of a coastal scene with an Impressionistic touch, focusing on the light and the leisure activities of figures by the sea.

He was influenced by the realism of Gustave Courbet and the modernism of Édouard Manet, artists who had earlier challenged academic conventions in France. Like Manet, Oppler often depicted scenes of contemporary leisure and social life. His connection with Lovis Corinth, a fellow Secessionist, is also notable; Corinth's own powerful, often more expressionistic take on Impressionism, provided a dynamic counterpoint within the German art scene. Oppler’s art sought a balance, often described as a blend of reality and poetry, capturing the tangible world while imbuing it with a sense of mood and atmosphere.

The Allure of Dance: Capturing Movement and Grace

One of the most distinctive and celebrated aspects of Ernst Oppler's oeuvre is his fascination with dance, particularly ballet. He became renowned for his paintings and, perhaps even more so, his etchings of dancers. This thematic focus aligns him with artists like Edgar Degas, who famously dedicated much of his career to depicting ballet dancers in Paris.

Oppler was particularly captivated by the performances of the Ballets Russes, Sergei Diaghilev's groundbreaking ballet company that toured Europe in the early 20th century and revolutionized the world of dance. The company, featuring legendary dancers such as Vaslav Nijinsky, Anna Pavlova, and Tamara Karsavina, was acclaimed for its innovative choreography, vibrant costumes, and avant-garde music. Oppler meticulously documented their performances in Germany, creating numerous sketches, paintings, and etchings that captured the dynamism, elegance, and drama of their art.

His representative work, the etching Karsavina dancing the polka in the ballet Les Vendredis, created around 1922-1923, is a prime example of his skill in this domain. It conveys the energy and grace of Tamara Karsavina, one of the leading ballerinas of the Ballets Russes. Similarly, his depictions of scenes from La Mort du Cygne (The Dying Swan), famously performed by Anna Pavlova, showcase his ability to capture the poignant emotion and fluid movement of the dance. These works are not merely static representations but seem to vibrate with the rhythm and motion of the performance.

Oppler's focus on dance allowed him to explore the human form in motion, the interplay of light on costumes and stage sets, and the expressive potential of gesture. His works in this genre are valuable not only as artistic achievements but also as historical records of a pivotal era in dance history. The German Dance Archives in Cologne (Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln) fittingly holds a significant collection of his work related to dance, underscoring his importance in this specialized field.

Mastery in Printmaking: The Art of Etching

While a proficient painter, Ernst Oppler also excelled as a printmaker, particularly in the medium of etching. Etching, with its incised lines and tonal possibilities, proved to be an ideal medium for his artistic sensibilities. It allowed for a delicacy of line and a subtlety of shading that suited his Impressionistic style and his interest in capturing fleeting effects of light and movement.

His etchings of dancers are particularly noteworthy. The technique allowed him to convey the swiftness of a gesture, the gossamer quality of a tutu, or the dramatic intensity of a performer's expression with remarkable precision and artistry. The linear quality of etching could define form, while techniques like aquatint could be used to create areas of tone, mimicking the play of light and shadow.

Beyond dance, Oppler applied his etching skills to other subjects, including portraits and genre scenes. His printmaking activities were an integral part of his artistic practice, allowing his work to reach a wider audience and demonstrating his versatility across different media. The ability to produce multiple impressions from a single plate also aligned with the growing interest in graphic arts during this period, as artists explored new ways to disseminate their work. His commitment to printmaking places him in a tradition of painter-etchers that includes artists like Rembrandt and, closer to his own time, Whistler, who also made significant contributions to the art of etching.

Oppler, Jewish Identity, and Architectural Echoes

Ernst Oppler's Jewish heritage, inherited from his architect father Edward Oppler, formed a part of his identity, though its explicit expression in his painting and printmaking is perhaps more subtle than in his father's architectural career. Edward Oppler was renowned for his synagogue designs, which often sought to create a distinctly German-Jewish architectural language, sometimes employing a Neo-Romanesque style.

The provided information suggests that Ernst Oppler himself made contributions to architectural design, particularly in the context of Jewish culture, aiming to blend Romanesque elements with Jewish traditions. This indicates an engagement with his heritage that extended beyond his primary artistic practice. If he was indeed involved in designing or conceptualizing religious or communal buildings, such as the tomb building in the Breslau Jewish cemetery mentioned in some evaluations, it would represent a fascinating, though perhaps lesser-known, facet of his career, echoing his father's legacy. Such work would have involved navigating the complex interplay of religious tradition, cultural identity, and contemporary architectural styles in Germany.

During World War I, Oppler served as a soldier, and it is recorded that he created paintings documenting his encounters with Eastern European Jews. These works could offer a more direct artistic engagement with Jewish life and identity, viewed through the lens of wartime experience. This period might have provided him with unique perspectives on Jewish communities different from his own assimilated German-Jewish background, potentially influencing his understanding and depiction of Jewish themes.

Wartime Experiences and Later Career

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 inevitably impacted the lives and careers of artists across Europe. Ernst Oppler served in the German military, and like many artists who experienced the war, this period found its way into his work. His paintings from this time included depictions of war scenes and, as mentioned, his encounters with Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. These works would have added another dimension to his oeuvre, reflecting the profound societal upheavals and personal experiences of the conflict.

After the war, Oppler continued his artistic career, with his focus on dance remaining particularly strong through the 1920s. The cultural landscape of Weimar Germany was vibrant and tumultuous, and Berlin was at its epicenter. Oppler, already an established figure, continued to exhibit and produce art. However, the artistic world was also evolving rapidly, with new movements like Expressionism (which had already taken strong root in Germany with artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde), Dada, and New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit, with figures such as Otto Dix and George Grosz) challenging the dominance of Impressionism.

While Oppler remained largely faithful to his Impressionistic style, his continued dedication to his craft ensured his presence in the art world. He passed away on March 1, 1929, in Berlin, just before the Weimar Republic began its final, turbulent years and the subsequent rise of Nazism, which would tragically lead to the persecution of Jewish artists and the suppression of "degenerate" modern art, including Impressionism.

Legacy, Collections, and Critical Reception

Ernst Oppler's works are held in numerous prestigious public collections, a testament to his contemporary recognition and enduring artistic value. These include the National Gallery in Berlin, the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, and the Modern Gallery in Venice. The Foosaner Art Museum in Florida has also recognized his importance, holding exhibitions of his work. The fact that his artistic estate, particularly relating to his dance imagery, is preserved in the German Dance Archives in Cologne further solidifies his specialized legacy.

Academic evaluation of Oppler acknowledges his skill as an Impressionist painter and a master etcher. His contributions to the Berlin Secession are recognized as part of the broader movement that modernized German art. His depictions of the Ballets Russes are considered particularly significant, both artistically and as historical documents. Frank-Manuel Peter's book, The Painter Ernst Oppler – The Berlin Secession & The Russian Ballet, provides a scholarly examination of these key aspects of his career.

Some critical discussions, particularly those touching upon architectural work attributed to "Oppler" (which may sometimes conflate Ernst with his father Edward), have noted a tension in the attempt to create a "German-Jewish" style, with some critics finding certain Neo-Romanesque designs to be a "disguise" rather than an authentic expression. If Ernst himself was involved in such architectural projects, he would have been part of this complex discourse on identity and style. His preference for what might be seen as more traditional or less avant-garde styles compared to the rising tide of Expressionism or later modernist movements might have led to him being somewhat overshadowed by more radical figures in some historical narratives. However, his consistent quality and his unique focus on certain themes, like dance, ensure his distinct place.

Conclusion: An Enduring Impression

Ernst Oppler was an artist of his time, deeply engaged with the artistic currents that swept through Europe at the turn of the 20th century. As a German Impressionist, he skillfully adapted the revolutionary techniques of light and color to his own vision, creating works that are both aesthetically pleasing and culturally insightful. His active role in the Berlin Secession underscores his commitment to artistic progress and freedom.

His most unique and perhaps most lasting contribution lies in his sensitive and dynamic portrayals of dance, particularly the groundbreaking performances of the Ballets Russes. Through his paintings and etchings, he captured the ephemeral magic of movement, preserving moments of artistic brilliance for posterity. While navigating a period of intense artistic innovation and societal change, Oppler carved out a distinct niche, leaving behind a legacy that continues to be appreciated for its elegance, technical mastery, and its insightful reflection of a vibrant cultural era. His work invites us to look closer at the nuances of German Impressionism and the rich artistic dialogues that shaped modern European art.