Alphonse Étienne Dinet stands as a unique and compelling figure within the diverse landscape of French Orientalist painting. Born in Paris in 1861 and passing away in the same city in 1929, Dinet dedicated much of his life and artistic output to capturing the essence of Algeria, a land that became not just his subject but his adopted home and spiritual center. Unlike many of his contemporaries who viewed the "Orient" through a lens of exoticism or colonial superiority, Dinet immersed himself deeply in Algerian culture, learned the language, formed profound friendships, and ultimately converted to Islam, taking the name Nasreddine Dinet. His work is characterized by a remarkable blend of academic precision, vibrant realism, and profound empathy, offering a window into the daily lives, landscapes, and spiritual world of the Algerian people he came to know so intimately.

Parisian Beginnings and Artistic Formation

Alphonse Étienne Dinet was born into a comfortable bourgeois Parisian family on March 28, 1861. His father, Philippe Léon Dinet, was a prominent judge, and his mother, Louise Marie Adèle, née Brière, was herself artistically inclined and supportive of her son's talents. This privileged background provided him with a solid education. Initially, he seemed destined to follow his father into law, but his passion for art soon took precedence.

In 1881, at the age of 19 or 20, Dinet enrolled at the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. There, he received rigorous academic training under respected masters of the time. His teachers included the history painter Victor Galland, known for his decorative work, and the highly influential academic painters William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. Bouguereau, in particular, was renowned for his technical perfection and idealized depictions, while Robert-Fleury was a celebrated portraitist and history painter. This training instilled in Dinet a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the realistic rendering of the human form.

During his studies, Dinet began exhibiting his work. He made his debut at the official Paris Salon in 1882. An early success came in 1883 when he received an honorable mention at the Salon. The following year, 1884, marked a pivotal moment: Dinet won a travel scholarship, the Prix du Salon, which enabled his first journey outside Europe. The destination he chose was Algeria.

The Lure of Algeria: First Encounters

In 1884, accompanied by fellow art student Lucien Simon, Dinet embarked on his first trip to Algeria. This journey took him to the southern regions, specifically around Bou-Saâda and Laghouat. The impact of North Africa was immediate and profound. The intense light, the vibrant colors, the stark beauty of the desert landscapes, and the distinct culture of the Algerian people captivated him completely. This initial experience contrasted sharply with the often-muted light and familiar subjects of his Parisian training.

He returned to Algeria the following year, 1885, this time traveling with a young Algerian guide named Sliman Ben Ibrahim, whom he had likely met during his first visit or shortly thereafter. This trip further solidified his fascination with the country. Sliman would become not only a guide and translator but also a lifelong friend, collaborator, and crucial link to understanding the nuances of Algerian life and Islamic culture.

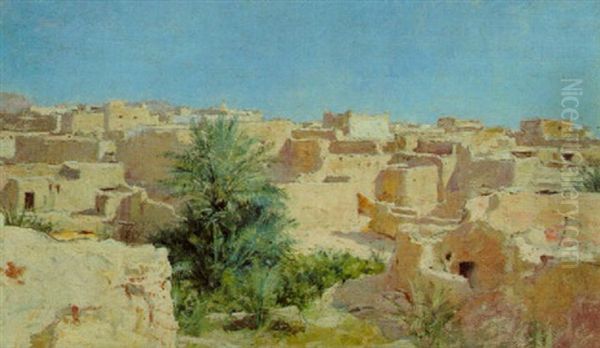

These early trips provided Dinet with a wealth of sketches, observations, and inspiration that would fuel his work for years to come. His paintings from this period began to reflect his experiences, depicting Algerian landscapes and scenes of daily life, though still often framed within the narrative or anecdotal style common in Orientalist painting at the time. Works like Les Terrasses de Laghouat (The Terraces of Laghouat, 1886) showcase his early engagement with Algerian architecture and light.

Bou-Saâda: An Adopted Home

While Dinet initially divided his time between France and Algeria, the pull of the North African nation grew increasingly strong. He continued to make frequent trips, often spending months at a time immersing himself in the local environment. Around 1904 or 1905, he made the significant decision to establish a permanent home in Bou-Saâda, an oasis town often called the "Gateway to the Desert," located south of Algiers.

His life in Bou-Saâda was markedly different from that of most European artists who visited the region. Dinet did not remain an outsider looking in; he actively integrated himself into the community. He dedicated himself to learning Arabic, eventually achieving fluency. This linguistic skill was crucial, allowing him to communicate directly with the local population, understand their perspectives, and gain access to aspects of their lives often closed off to foreigners.

He built a house and studio in Bou-Saâda and lived there for much of the remainder of his life, nearly fifty years in total association with Algeria. He formed deep and lasting friendships, most notably with Sliman Ben Ibrahim, but also with many other members of the community. This immersion allowed him to move beyond superficial observations and develop a genuine understanding and respect for the local customs, traditions, and religious beliefs. His long-term residency provided him with unparalleled insight, distinguishing his work from the fleeting impressions captured by many visiting artists.

Artistic Style: Realism, Light, and Empathy

Dinet's artistic style evolved throughout his career, but it remained rooted in the academic realism of his training, infused with the unique qualities of his chosen subject matter. He became a master at capturing the specific effects of North African light – its intensity, clarity, and the way it defined forms and saturated colors. His palette became brighter and more vibrant compared to his earlier work, employing warm ochres, deep blues, and brilliant whites to convey the sun-drenched landscapes and colorful attire.

He employed strong contrasts between light and shadow, not just for dramatic effect but also to model forms and create a sense of depth and atmosphere, as seen in works depicting interiors or shaded alleyways like Seducer. His compositions were carefully constructed, often focusing on scenes of everyday life: people praying, children playing, women performing domestic tasks, men gathered in conversation, or vibrant celebrations.

What truly set Dinet apart from many contemporary Orientalists, such as the highly skilled but sometimes criticized Jean-Léon Gérôme, was his empathetic and respectful approach. While Orientalism often involved projecting Western fantasies, stereotypes, or a sense of the exotic onto North African and Middle Eastern cultures, Dinet strove for authenticity. He depicted his subjects with dignity and humanity, avoiding the sensationalism, overt eroticization (particularly of women), or condescension found in some Orientalist art. His deep knowledge of the culture and his personal relationships allowed him to portray religious practices, social interactions, and individual personalities with sensitivity and insight. His approach shares affinities with other sympathetic Orientalists like Eugène Fromentin or Gustave Guillaumet, who also spent considerable time in Algeria.

Masterpieces and Representative Works

Dinet's extensive oeuvre includes numerous paintings that are considered highlights of Orientalist art and testament to his unique vision.

_Girls Dancing and Singing_ (1902): Perhaps one of his most famous works, this painting captures the joyous energy of young Algerian girls celebrating. The vibrant colors of their clothing, the dynamic movement, and the sunlit setting exemplify Dinet's ability to convey both cultural specificity and universal human emotion. It showcases his mastery of color and light to create a lively, celebratory atmosphere.

_L’Ecole Coranique_ (The Quranic School): This work depicts young boys studying the Quran under the guidance of a teacher. It reflects Dinet's interest in the religious and educational aspects of Algerian life. The painting is noted for its detailed observation of the setting and the focused expressions of the figures, offering a respectful glimpse into Islamic tradition.

_Médahh_ (The Storyteller/Drummer): This painting portrays a traditional storyteller or musician captivating an audience. It highlights the importance of oral traditions and performance in Arab culture, a subject Dinet understood through his immersion. The composition draws the viewer into the intimate circle of listeners.

_Head of an Algerian Youth_: Often executed in tempera, Dinet's portraits, like this example, demonstrate his skill in capturing individual likeness and character. The fine detail and sensitive rendering convey a sense of presence and psychological depth, treating the subject not as an exotic type but as a distinct person.

_Young Girl with a Veil_ (1901): This intimate portrait showcases Dinet's ability to depict Algerian women with sensitivity, focusing on the individual behind cultural attire, challenging the often objectifying gaze found elsewhere in Orientalist art.

Cairo Panoramas (c. 1897): Following a trip to Egypt, Dinet created impressive panoramic views of Cairo, capturing the city at different times of day (morning and evening). These works demonstrate his skill in rendering complex cityscapes and atmospheric effects, particularly the changing quality of light.

_Abd el Gheram and Nouriel Ain, Slaves of Love and Light of the Eyes_: This title points towards works exploring themes of love and local legends, often imbued with a poetic quality derived from Arabic literature and folklore, which Dinet studied and translated.

These works, among many others, illustrate the breadth of Dinet's interests, from landscape and portraiture to genre scenes and religious subjects, all rendered with his characteristic blend of realism and cultural sensitivity.

Collaboration and Friendship: Sliman Ben Ibrahim

The relationship between Étienne Dinet and Sliman Ben Ibrahim was central to the artist's life and work in Algeria. Meeting in 1885 or shortly after, Sliman, who was considerably younger than Dinet, became far more than just a guide. He was Dinet's primary Arabic teacher, cultural interpreter, collaborator, and closest friend for over four decades.

Sliman provided Dinet with invaluable insights into the nuances of Algerian Arab culture, Islamic faith, traditions, and social customs. This deep understanding, facilitated by Sliman, permeates Dinet's art, lending it an authenticity rare among European Orientalists. Their friendship was based on mutual respect and intellectual exchange.

Their collaboration extended beyond the visual arts into the literary realm. Together, they co-authored several books aimed at explaining Arab life and Islamic culture to a Western audience. Sliman's contribution was essential, providing firsthand knowledge and perspective, while Dinet brought his writing skills and understanding of the European readership. This partnership underscores Dinet's commitment to genuine cultural exchange rather than mere artistic appropriation.

Conversion to Islam: Nasreddine Dinet

Dinet's long immersion in Algerian life and his deep study of Islamic culture culminated in his formal conversion to Islam in 1913. He publicly announced his conversion and adopted the Muslim name Nasreddine (sometimes rendered Nasr ad-Din or Nasreddin), meaning "Defender of the Faith." This was a profound step, signifying his complete identification with the culture and religion he had come to admire and respect so deeply.

His conversion was not a superficial gesture. It stemmed from years of study, reflection, and personal connection with the Muslim community in Bou-Saâda. It further deepened his understanding and informed his later artistic production, which increasingly included explicitly religious themes depicted with reverence and insight, such as scenes of prayer or illustrations for Islamic texts.

His identity as Nasreddine Dinet was fully embraced. In 1929, shortly before his death, he fulfilled a lifelong dream by undertaking the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, accompanied by his dear friend Sliman Ben Ibrahim. This journey represented the pinnacle of his spiritual commitment. His conversion made him a unique figure – a European artist celebrated in the West who was also a practicing Muslim deeply respected within his adopted Algerian community.

Literary Pursuits and Cultural Bridging

Beyond his prolific painting career, Dinet was also an accomplished writer and translator. His fluency in Arabic allowed him to engage directly with Arabic literature. In 1898, he published a translation of the 13th-century Arab epic poem Antar. This was a significant contribution, making a classic of Arab literature accessible to French readers.

His most notable literary collaboration with Sliman Ben Ibrahim was La vie de Mohammed, prophète d’Allah (The Life of Muhammad, Prophet of Allah), published in 1918. This biography was significant not only for its content, offering a sympathetic portrayal of the Prophet Muhammad for a European audience, but also for its context. Published during World War I, it implicitly challenged the prejudices faced by Muslim soldiers fighting for France. Intriguingly, scholars note that this book contains one of the earliest documented uses of the term "Islamophobia" in French, used by Dinet and Sliman to denote a systematic prejudice against Islam.

Dinet also authored and illustrated other books, such as Tableaux de la Vie Arabe (Pictures of Arab Life), further explaining the customs and culture he observed. Through his paintings, translations, and writings, Dinet acted as a crucial cultural bridge, fostering understanding between France and the Arab-Islamic world during a period often marked by colonial tensions and misunderstanding.

Recognition, Associations, and Contemporaries

Étienne Dinet achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, both in France and internationally. He exhibited regularly at the Paris Salon and other major exhibitions. His accolades included an honorable mention (1883), a third-class medal (1884), and prestigious awards at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fairs) in Paris: a silver medal in 1889 and a gold medal in 1900. In 1905, his contributions to French art and culture were recognized when he was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour.

Dinet played a key role in the institutional promotion of Orientalist art. In 1893, he was one of the founding members of the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français (Society of French Orientalist Painters), serving alongside figures like the curator Léonce Bénédite. This society organized regular exhibitions and became a major platform for artists working with North African and Middle Eastern themes. Fellow exhibitors and prominent Orientalists associated with the era included Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant, Ludwig Deutsch, Rudolf Ernst, and Théodore Chassériau.

His work was admired by critics and collectors, and he was seen as a leading figure in the later phase of Orientalism. His unique position, straddling French and Algerian culture, garnered attention. He was also connected to other artists who depicted Algeria, such as Eugène Alexis Girardet, whose ethnographic focus reportedly influenced Dinet's shift away from purely anecdotal scenes. While distinct in his approach, Dinet operated within a broader artistic milieu that included pioneers like Eugène Delacroix and contemporaries like the American Frederick Arthur Bridgman, who also painted extensively in North Africa.

Later Life, Death, and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Nasreddine Dinet continued to paint and write, dividing his time between his beloved Bou-Saâda and Paris. His commitment to his faith deepened, culminating in the Hajj pilgrimage in 1929. Tragically, shortly after returning from Mecca, he fell ill. Alphonse Étienne Nasreddine Dinet died of a heart attack in his Paris apartment on December 24, 1929.

His death was mourned in both France and Algeria. While he died in Paris, his body was transported back to Bou-Saâda for burial according to his wishes and Islamic rites. His funeral in Bou-Saâda in January 1930 was a remarkable event, attended by thousands of people – local Algerians and French officials alike – a testament to the immense respect and affection he commanded in his adopted homeland. He was buried in Bou-Saâda, and his tomb remains a site of reverence.

Dinet's legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he left behind a rich body of work celebrated for its technical skill, vibrant depiction of Algerian life, and unique empathetic perspective. He is considered one of the most important and authentic Orientalist painters. His deep immersion and conversion distinguished him sharply from artists who merely visited the "Orient" for exotic subject matter.

In Algeria, he is remembered with particular fondness, often referred to as "the painter of Bou-Saâda" or even "Algeria's painter." The Musée National Nasreddine Dinet in Bou Saâda stands as a permanent tribute to his life and work, preserving his memory and artistic contributions within the culture he loved. His life story continues to fascinate as an example of profound cross-cultural engagement and personal transformation. He remains a significant figure in the study of Orientalism, Franco-Algerian relations, and the intersection of art, culture, and religion. His influence can also be seen in artists who followed, perhaps even indirectly inspiring figures like Charles de Pouvreau-Baldy through his dedication to capturing profound human experiences.

Dinet in the Context of Orientalism

Placing Alphonse Étienne Dinet within the broader context of Orientalism highlights his unique position. The Orientalist movement, particularly in the 19th century, encompassed a wide range of European artists depicting North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. While often producing visually stunning works, the movement has faced criticism, notably articulated by Edward Said, for sometimes perpetuating stereotypes, exoticizing or eroticizing cultures, and reflecting colonial attitudes.

Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, while technically brilliant, often focused on scenes of harems, slave markets, or dramatic historical reconstructions that catered to Western tastes for the exotic and sometimes reinforced biased views. Others, like the early pioneer Eugène Delacroix, were captivated by the dynamism and color but spent relatively little time immersed in the culture compared to Dinet.

Dinet, along with figures like Gustave Guillaumet, represents a different strand within Orientalism – one characterized by long-term engagement, ethnographic interest, and a more sympathetic portrayal of local populations. Dinet's fluency in Arabic, his decades-long residency, his close friendships, and ultimately his conversion to Islam gave him an unparalleled insider's perspective. His work generally avoids the ethnographic gaze that reduces individuals to types, instead focusing on personal interactions, daily routines, and spiritual life with respect and understanding. While still a European artist working within the Orientalist tradition, his deep integration into Algerian society allowed him to transcend many of the limitations and biases associated with the movement.

Conclusion: A Painter Between Worlds

Alphonse Étienne Dinet's life and art represent a remarkable journey of cultural immersion and personal transformation. From his academic training in Paris to his adopted home in the Algerian oasis of Bou-Saâda, he dedicated himself to understanding and portraying a world far removed from his origins. His paintings, characterized by vibrant realism, sensitivity to light and color, and profound empathy, offer a unique and respectful window into Algerian life at the turn of the 20th century.

His conversion to Islam and adoption of the name Nasreddine Dinet solidified his unique position as a bridge between French and Algerian cultures. Through his art, his translations, and his writings co-authored with Sliman Ben Ibrahim, he sought to foster understanding and challenge prejudice. Celebrated in France for his artistic achievements and revered in Algeria for his genuine connection to its people and culture, Dinet's legacy endures. He remains a testament to the power of art to transcend boundaries and the profound impact of dedicating one's life to understanding another culture from the inside out.