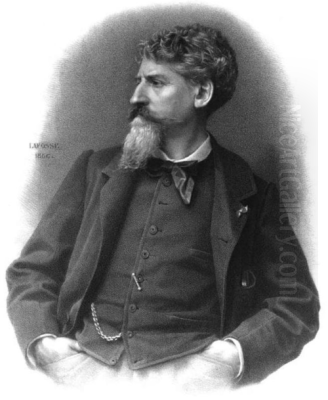

Eugène Pierre François Giraud (1806-1881) stands as a notable figure in the vibrant landscape of 19th-century French art. A painter, engraver, and designer, Giraud navigated the artistic currents of his time with skill and versatility, leaving behind a body of work that reflects the era's fascination with history, exoticism, and the nuanced portrayal of human emotion. His career, marked by prestigious awards, influential travels, and significant connections, offers a compelling window into the world of a Parisian artist deeply embedded in the Romantic movement.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Born in Paris in 1806, Eugène Giraud was immersed in a city that was the undisputed epicenter of the European art world. His formal artistic education took place at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the leading art institution in France. Here, aspiring artists received rigorous training grounded in classical principles, drawing from antique sculpture and studying the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters. This academic foundation was crucial for any artist seeking official recognition and success.

During his studies, Giraud had the privilege of being mentored by Louis Hersent (1777-1860). Hersent was a respected painter of historical subjects and portraits, a member of the Institut de France, and a professor at the École. He had himself been a student of Jean-Baptiste Regnault, a prominent Neoclassical painter. Under Hersent's guidance, Giraud would have honed his skills in draughtsmanship, composition, and the traditional techniques of oil painting, preparing him for the competitive environment of the Parisian art scene.

The culmination of this early training was Giraud's triumph in winning the coveted Prix de Rome in 1826. This highly competitive prize, awarded by the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the ultimate recognition for a young artist. It provided a scholarship for a period of study at the French Academy in Rome, located in the Villa Medici. For Giraud, this was a transformative opportunity, allowing him to immerse himself in the artistic treasures of Italy and further refine his craft.

The Italian Sojourn: Inspiration and Development

The years spent in Italy following the Prix de Rome were profoundly influential for Giraud, as they were for generations of artists before and after him. Rome, with its unparalleled access to classical antiquities and masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, was an open-air museum and an unparalleled school. Artists like Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres had famously benefited from their time in Italy, and Giraud was poised to do the same.

During his Italian stay, Giraud would have diligently sketched ancient ruins, studied the works of Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, and Caravaggio, and absorbed the unique light and atmosphere of the Italian landscape. This period was not merely about copying; it was about internalizing the lessons of the masters and finding one's own artistic voice. It was in Italy that Giraud created significant works, including the painting "The Crown of Thorns," a piece that likely reflected his engagement with religious themes and the dramatic intensity often found in Italian art.

The experience in Italy broadened his thematic and stylistic horizons. The exposure to different schools of painting and the vibrant artistic community in Rome, which included artists from across Europe, would have enriched his perspective. This period laid a crucial foundation for his subsequent career, equipping him with a sophisticated understanding of art history and a refined technical skill set.

A Parisian Career: The Salon and Society

Upon his return to Paris, Eugène Giraud embarked on a professional career, seeking to establish his reputation and secure patronage. The primary avenue for an artist to gain public recognition and attract commissions was the Paris Salon. This official, juried exhibition, organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was a major cultural event, drawing vast crowds and intense critical scrutiny. Giraud regularly submitted his works to the Salon, a necessary step for any ambitious artist.

His paintings exhibited at the Salon showcased his versatility. He was adept at historical paintings, a genre highly esteemed by the Academy, which often depicted grand narratives from mythology, religion, or national history. These works required not only technical skill but also erudition and the ability to convey complex stories and emotions. Giraud's academic training and his time in Italy provided him with the necessary tools for success in this demanding genre.

Beyond historical subjects, Giraud also excelled in landscape painting and portraiture. His landscapes often captured the picturesque beauty he had encountered in his travels, while his portraits were sought after for their likeness and characterization. He was known for his ability to depict idealized mythological and historical scenes, imbuing them with a sense of drama and romance that appealed to contemporary tastes. His success at the Salon was affirmed by medals awarded in 1833 and 1863, recognizing the quality and impact of his contributions.

The Romantic Spirit and Thematic Choices

Eugène Giraud's artistic output aligns closely with the tenets of Romanticism, the dominant artistic and intellectual movement of the first half of the 19th century. Romanticism emerged as a reaction against the perceived cold rationalism of Neoclassicism, emphasizing instead emotion, individualism, the power of nature, and a fascination with the past, particularly the medieval period, and exotic locales.

Giraud's historical and mythological paintings often resonated with Romantic sensibilities. He chose subjects that allowed for dramatic compositions, expressive figures, and rich color palettes. Unlike the stoic heroism often found in Neoclassical works by artists like Jacques-Louis David, Romantic historical paintings, such as those by Eugène Delacroix or Théodore Géricault, explored a wider range of human experiences, including passion, suffering, and the sublime. Giraud's depictions of idealized scenes fit within this broader trend, offering viewers an escape into worlds of heightened emotion and visual splendor.

His interest in landscape painting also connected with Romantic ideals, which saw nature not merely as a backdrop but as a source of spiritual and emotional experience. The portrayal of specific, often dramatic, natural settings became a hallmark of Romantic landscape artists like Caspar David Friedrich in Germany or J.M.W. Turner in England. While Giraud's landscapes might not have reached the same level of visionary intensity, they shared the Romantic appreciation for the particularities of place and atmosphere.

Journeys of Inspiration: Spain and the "Orient"

Travel played a crucial role in shaping Giraud's artistic vision and providing him with fresh subject matter, a characteristic he shared with many Romantic artists. The allure of the "Orient"—a term then used broadly to refer to North Africa, the Middle East, and sometimes Spain—was particularly potent during this period. These regions were perceived as exotic, sensual, and untamed, offering a stark contrast to industrialized Europe.

Around 1846-1847, Giraud embarked on a significant journey to Spain and North Africa (specifically Algeria and Egypt). He was in distinguished company, traveling with the celebrated writer Alexandre Dumas père (father) and his son, Alexandre Dumas fils (also a writer), as well as the fellow Romantic painter Louis Boulanger (1806-1867). Boulanger was a close friend of Victor Hugo and known for his historical and literary scenes. This expedition would have been an adventure, exposing Giraud to new cultures, landscapes, and artistic traditions.

The vibrant colors, intense light, and unfamiliar customs of Spain and North Africa provided a wealth of inspiration. This experience fueled the Orientalist trend in his work, a popular subgenre of Romanticism seen in the paintings of artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Fromentin, and, most famously, Delacroix, whose own trip to Morocco in 1832 was transformative. Giraud's sketches and paintings from these travels would have captured scenes of daily life, local costumes, and dramatic landscapes, appealing to the Parisian public's taste for the exotic.

Another notable trip to Spain occurred when Giraud accompanied the writer and occultist Adolphe Desbarolles. They traveled to Madrid to attend the wedding of the Duc de Montpensier (son of King Louis-Philippe I of France) to Infanta Luisa Fernanda of Spain in 1846. This journey, traversing from Cadiz to Madrid, offered further immersion in Spanish culture and likely provided opportunities for Giraud to observe and sketch aristocratic life and ceremonial events, adding another dimension to his repertoire of subjects.

Master of Portraiture

Portraiture was a significant aspect of Eugène Giraud's oeuvre, and he demonstrated considerable skill in capturing both the likeness and the personality of his sitters. In an era before photography became widespread, painted portraits were essential for commemorating individuals and asserting social status. Giraud's ability to produce refined and insightful portraits made him a sought-after artist in this field.

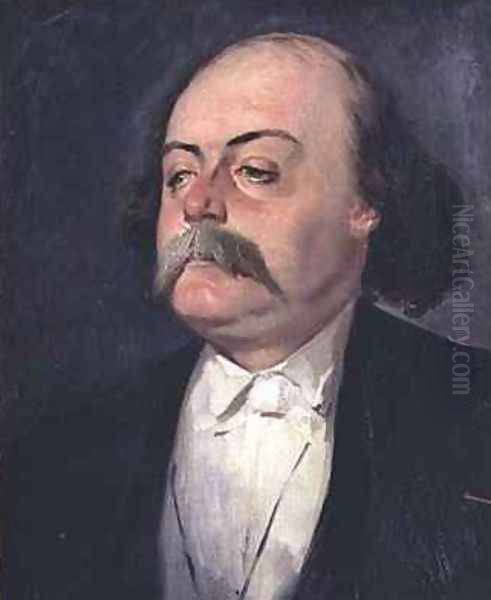

One of his most famous portraits is that of the renowned writer Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), the author of "Madame Bovary." This painting, now housed in the Château de Fontainebleau, is a sensitive portrayal of the literary giant. Such a commission indicates Giraud's standing within artistic and intellectual circles. To paint a figure of Flaubert's stature was a mark of distinction. The Goncourt brothers, Edmond and Jules, prominent literary figures and art critics themselves, were also part of this milieu, and it's plausible Giraud had interactions with them, given their shared Parisian cultural landscape.

Another documented portrait is that of Madame Desbarres, exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1834. This work would have showcased his talent for depicting contemporary figures, likely with the elegance and attention to detail expected in society portraiture. His portraits, like those of his teacher Hersent or contemporaries like Franz Xaver Winterhalter (though Winterhalter focused more on royalty), aimed to convey not just physical features but also a sense of the sitter's character and social standing.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Beyond his portraits and grand historical scenes, Eugène Giraud also produced genre paintings, which depict scenes of everyday life, often with a narrative or anecdotal quality. Two such works mentioned are "The Lovers' Tiff" and "The Secret Letter." These titles suggest intimate, slightly sentimental scenes, popular with the bourgeois audience of the 19th century. Such paintings often told a story, inviting viewers to imagine the circumstances and emotions of the figures depicted.

These works, often executed on a smaller scale than his historical canvases, would have showcased Giraud's skill in rendering textures, fabrics, and interior details, as well as his ability to convey subtle psychological interactions between figures. Artists like Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier achieved immense fame with meticulously detailed historical genre scenes, and while Giraud's style might have differed, the appeal of narrative genre painting was widespread.

"The Crown of Thorns," created during his time in Italy, points to his engagement with religious subject matter. Such themes, central to the academic tradition, allowed artists to explore profound human emotions and create compositions of great dramatic power, following in the footsteps of masters like Titian or Guido Reni. The success of these varied works in different genres underscores Giraud's versatility as an artist.

Giraud and His Contemporaries

Eugène Giraud's career unfolded during a dynamic period in French art, and he was connected, either directly or indirectly, with many leading figures of his time. His teacher, Louis Hersent, linked him to the established academic tradition. His travels with Alexandre Dumas père and Louis Boulanger placed him firmly within Romantic literary and artistic circles. Boulanger, in particular, was a key figure in the Romantic movement, closely associated with Victor Hugo and known for works inspired by literature and history.

The towering figure of Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) dominated French Romantic painting. While Giraud may not have achieved Delacroix's revolutionary impact, he operated within the same artistic climate, sharing an interest in historical drama, vibrant color, and exotic subjects. Similarly, Théodore Géricault (1791-1824), though his career was tragically short, had set a powerful precedent for Romantic expression with works like "The Raft of the Medusa."

In the realm of academic art, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) represented a more classical strand of Romanticism, emphasizing linear precision and idealized form. Giraud, like many artists, would have navigated the space between the overt emotionalism of Delacroix and the refined classicism of Ingres. Other prominent historical painters of the era included Paul Delaroche, known for his meticulously rendered and often sentimental historical scenes, and Horace Vernet, celebrated for his battle paintings and Orientalist subjects.

Giraud's portrait of Gustave Flaubert connects him to the literary world, which also included figures like Théophile Gautier, a poet, novelist, and influential art critic. The Goncourt brothers, as diarists and critics, documented the artistic and literary life of Paris, and artists like Giraud would have been part of the Salon scene they observed and wrote about.

While a direct "close contact" with a younger artist like Edgar Degas (1834-1917) is not extensively documented beyond general Parisian art circles, Giraud, as an established Salon painter, would have been a known figure. Degas, emerging in the later part of Giraud's career, would eventually break from the Salon system with the Impressionists, but he too received academic training and initially exhibited at the Salon. Giraud would also have been aware of other contemporary painters like Benjamin Ullmann, who moved in similar artistic spheres. The influence of earlier masters like Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806), whose Rococo charm and painterly freedom offered a rich legacy, would have been part of the artistic consciousness of Giraud's generation, even if direct personal interaction was impossible due to Fragonard's death in Giraud's birth year.

The Engraver and Designer

Eugène Giraud's talents were not confined to painting. He was also an accomplished engraver and printmaker. In the 19th century, engraving was a vital means of reproducing and disseminating images, making artworks accessible to a wider public before the advent of photomechanical reproduction. Many painters, including Ingres and Delacroix, also produced prints. Giraud's work in this medium would have allowed his compositions, whether original designs or reproductions of his paintings, to reach a broader audience.

Furthermore, Giraud engaged in stage design. This aspect of his career was likely facilitated by his close relationship with Alexandre Dumas père, a prolific playwright. Designing costumes and sets for theatrical productions required a strong sense of historical accuracy, visual flair, and an understanding of dramatic effect—skills that Giraud possessed as a historical painter. This work connected him directly to the vibrant theatrical world of Paris, another key component of the city's cultural life. His brother, also named Eugène Giraud (Pierre François Eugène was his full name, often leading to confusion or reference to him as "Eugène Giraud the elder" if his brother was also an artist of note), was reportedly also a painter, suggesting a familial artistic environment.

Later Years and Legacy

Eugène Pierre François Giraud continued to work and exhibit throughout his life. His consistent presence at the Paris Salon and the awards he received attest to a sustained career and a respected position within the French art establishment of his time. He successfully navigated the changing tastes and artistic currents of the 19th century, adapting his skills to various genres and maintaining a reputation for quality and professionalism.

He passed away in 1881 at the age of 75, leaving behind a significant body of work that reflects the artistic preoccupations of his era. While he may not be as universally recognized today as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries like Delacroix or later, Courbet and the Impressionists, Giraud's contributions are important for understanding the breadth and depth of 19th-century French art.

His paintings are found in various museum collections, including the previously mentioned portrait of Flaubert in Fontainebleau, and his works occasionally appear at auction, attesting to a continued appreciation among collectors. His legacy is that of a skilled and versatile artist who successfully embodied many aspects of the Romantic movement, from its historical grandeur to its fascination with the exotic and its appreciation for individual character in portraiture.

Art Historical Significance and Reception

In the grand narrative of art history, Eugène Pierre François Giraud is recognized as a competent and respected representative of French Romanticism and academic art. He was an artist who mastered the technical skills demanded by the École des Beaux-Arts and the Salon, and who applied these skills to a range of subjects that resonated with contemporary audiences. His winning of the Prix de Rome early in his career marked him as a talent of significant promise, a promise he largely fulfilled through a long and productive career.

His work is generally well-regarded for its technical proficiency, its pleasing compositions, and its engagement with the popular themes of his day. There is little evidence of major controversy surrounding his art or his person; he appears to have been a professional artist who worked diligently within the established systems of patronage and exhibition.

While Romanticism itself involved a break from Neoclassical conventions, Giraud's brand of Romanticism was not typically of the rebellious or avant-garde variety. He operated comfortably within the Salon system, which, while sometimes criticized for its conservatism, was the main arbiter of artistic success for much of the 19th century. His historical paintings, portraits, and genre scenes contributed to the rich tapestry of French art during a period of profound social and cultural change.

Eugène Giraud's art provides valuable insight into the tastes and values of his time. His depictions of historical and mythological scenes, his portraits of notable figures, and his Orientalist works all reflect the cultural currents that shaped 19th-century France. As an artist who successfully combined academic training with a Romantic sensibility, and who explored diverse genres and media, Eugène Pierre François Giraud remains a noteworthy figure in the history of French art.