Federico Zuccaro stands as a pivotal figure in the complex artistic landscape of late sixteenth-century Italy. Born around 1540/1542 in Sant'Angelo in Vado, near Urbino, he emerged from an artistic family, destined to leave a significant mark not only through his prolific output as a painter but also as an influential art theorist and a key player in the establishment of formal art education. His career spanned several decades, witnessing the evolution from High Renaissance ideals to the sophisticated, often intellectually charged style of Mannerism, and touching upon the nascent stirrings of the Baroque. Alongside his elder brother, Taddeo Zuccaro, Federico navigated the competitive artistic environments of Rome, Florence, Venice, and even ventured abroad, leaving a legacy that is both celebrated and debated.

Early Life and Collaboration with Taddeo

Federico's artistic journey began under the tutelage of his brother, Taddeo Zuccaro (c. 1529–1566). Taddeo was already establishing himself as a prominent painter in Rome when Federico joined him around 1550. This apprenticeship provided Federico with invaluable training and immediate access to significant commissions. The Zuccaro workshop became a major force in Roman decoration during the mid-16th century, known for its efficiency and ability to execute large-scale fresco cycles in the prevailing Mannerist style.

Together, the brothers worked on prestigious projects, including decorations for Pope Pius IV in the Vatican Palace. Their most celebrated collaboration was arguably the extensive fresco cycle depicting the history of the Farnese family in the Villa Farnese at Caprarola, a monumental undertaking that showcased their skill in complex narrative compositions and elegant figural representation. While Taddeo was often seen as the primary creative force in these early years, Federico quickly developed his own distinct abilities, contributing significantly to the workshop's success.

However, the relationship was not without friction. An anecdote from around 1555 suggests a moment of intense rivalry. Federico, having secured an independent commission, reportedly felt undermined by Taddeo's interference, leading him to deface some of his brother's work in anger. Though reconciliation followed, this incident hints at Federico's burgeoning ambition and desire to establish his own artistic identity, separate from his elder brother's shadow. Taddeo's premature death in 1566 left Federico to inherit the workshop's reputation and ongoing projects, fully launching his independent career.

Independent Career and Pan-European Travels

Following Taddeo's death, Federico stepped into the limelight, completing unfinished projects and securing new commissions. His reputation grew rapidly. Between 1563 and 1565, even before Taddeo's passing, Federico had spent time in Venice. This period was crucial, exposing him to the rich colorism and dynamic compositions of the Venetian school, particularly the works of masters like Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese. While in the Veneto region, he is also noted to have collaborated with the great architect Andrea Palladio, broadening his artistic horizons beyond painting.

His travels did not stop there. In 1565, he moved to Florence, a city steeped in the tradition of disegno (drawing and design), which resonated with his Central Italian training. His most significant Florentine commission would come later, but his presence there connected him with the artistic circle around the Medici court and the Accademia del Disegno.

Federico's ambition and growing fame led him further afield. He undertook significant journeys, working for patrons across Europe. He spent time in the Spanish Netherlands and, notably, in England from 1574 to 1575. During his English sojourn, he is traditionally credited with painting portraits of Queen Elizabeth I and members of her court, such as Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. While some attributions remain debated by scholars, these works, often characterized by detailed rendering of costume and a certain formal stiffness, reflect the specific demands of Elizabethan portraiture and Zuccaro's adaptability.

Later, between 1585 and 1588, Federico answered a call from King Philip II of Spain to work at the Escorial palace. This prestigious invitation placed him at one of the most important centers of European patronage. However, his contributions, primarily altarpieces, reportedly did not entirely satisfy the King's austere tastes, which increasingly favored a different style of devotional painting. This experience, though perhaps not wholly successful, underscores Federico's international standing.

Major Fresco Cycles and Monumental Works

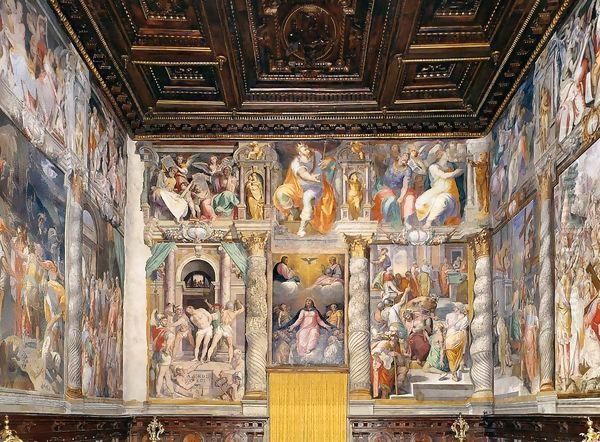

Federico Zuccaro's fame rests significantly on his large-scale fresco decorations, which adorned palaces and churches across Italy. He inherited the responsibility for completing the decoration of the Sala Regia in the Vatican Palace, a task begun by other artists. His fresco depicting The Emperor Frederick Barbarossa Paying Homage to Pope Alexander III is a notable example of his work in this prestigious space, demonstrating his ability to handle complex historical narratives with Mannerist elegance and compositional skill.

Perhaps his most famous, and controversial, monumental project was the completion of the frescoes on the interior of the dome of Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore). Giorgio Vasari had begun the vast Last Judgment fresco shortly before his death in 1574. Federico Zuccaro, assisted by artists like Domenico Passignano, took over the immense task between 1576 and 1579. Working high above the cathedral floor, he adapted Vasari's initial designs but infused the work with his own distinct style.

The resulting fresco is a swirling, densely populated vision of Heaven and Hell, rendered with dramatic foreshortening and expressive figures. It remains one of the largest single fresco paintings in the world. However, the work drew considerable criticism from Florentine observers, who found its style perhaps too Roman or overly complex compared to the Florentine tradition. Zuccaro's depiction of the damned, in particular, was seen by some as indecorous. This critical reception deeply affected Zuccaro, prompting defensive and even satirical responses. A section known as The Saved showcases his handling of celestial figures within this grand scheme.

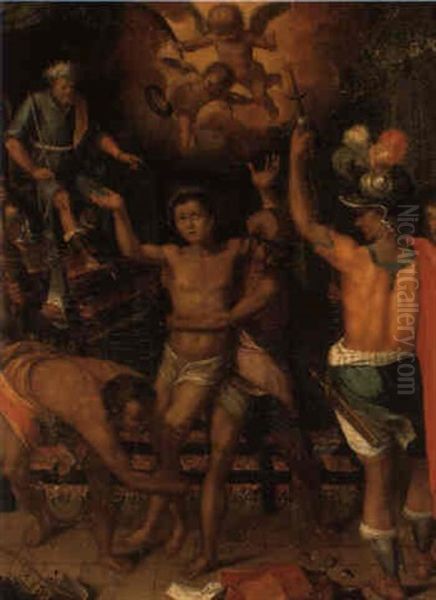

Other significant religious commissions included the Flagellation of Christ, painted in 1573 for the Oratorio del Gonfalone in Rome, a confraternity known for commissioning works from leading artists. He also executed frescoes in the Pauline Chapel (Cappella Paolina) in the Vatican, further cementing his status as a favored painter for high-profile religious decorations. His work extended to numerous other churches and palaces in Rome and other Italian cities.

Artistic Style: Mannerism and Beyond

Federico Zuccaro is primarily identified as a leading exponent of late Italian Mannerism. This style, which emerged after the High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, often emphasized artifice, elegance, and intellectual complexity over naturalism and classical harmony. Zuccaro's work typically exhibits key Mannerist traits: elongated figures, intricate and crowded compositions, sophisticated use of allegory and symbolism, and a strong emphasis on disegno – the conceptual and technical skill of drawing.

His figures often possess a graceful, serpentine quality (the figura serpentinata), arranged in complex poses. His compositions can be dense, filled with narrative detail and secondary figures, demanding careful reading from the viewer. He excelled at large-scale narrative cycles, where he could deploy his skills in organizing multiple figures and architectural settings. His color palette, while capable of richness, often prioritized clarity of form and line.

Compared to the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio, who emerged towards the end of Zuccaro's career, or the dynamic energy and painterly freedom of Tintoretto, Zuccaro's style appears more controlled, academic, and rooted in Central Italian traditions of drawing. His work often reflects the intellectual climate of the Counter-Reformation, employing complex allegories to convey religious or moral messages.

However, some accounts suggest that his later works, perhaps influenced by his experiences and the changing artistic tides, moved towards a quieter, somewhat more naturalistic mode. Works like The Virgin and Child with Saints (1603) might reflect this subtle shift. Nonetheless, his core identity remained tied to the sophisticated language of Mannerism, which he practiced and promoted throughout his long career.

Zuccaro the Theorist: L'Idea

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Federico Zuccaro made a lasting contribution to art theory with his book, L'idea de' Pittori, Scultori e Architetti (The Idea of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects), published in Turin in 1607, though likely developed over many years. This treatise stands as one of the most important theoretical texts of the late Mannerist period, offering insights into Zuccaro's conception of the artistic process and the status of the artist.

Central to Zuccaro's theory was the concept of disegno, which he divided into disegno interno (internal design) and disegno esterno (external design). The disegno interno represented the divine spark, the initial concept or idea originating in the artist's mind, seen as a reflection of God's own creative power. This elevated the intellectual and conceptual aspect of art above mere manual skill. The disegno esterno was the physical manifestation of this internal idea through drawing, painting, or sculpting.

Zuccaro argued passionately for the nobility of the arts, placing painting, sculpture, and architecture among the liberal arts rather than mere crafts. He believed that artistic creation stemmed from divine inspiration and intellectual effort, thus justifying a higher social status for artists. His book aimed to provide a philosophical and metaphysical foundation for artistic practice, drawing on Neoplatonic ideas about beauty and divine emanation.

While influential, L'Idea was also criticized, even in its time. Some contemporaries found its arguments overly complex, abstract, or even self-serving, designed primarily to elevate Zuccaro's own status and theoretical position. Nevertheless, the book played a significant role in shaping academic art theory and contributed to the ongoing discourse about the nature of art and the role of the artist, influencing discussions within art academies for generations.

Founding the Accademia di San Luca

Federico Zuccaro's commitment to elevating the status of artists and formalizing their training found its most concrete expression in his role in founding the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. While artists' guilds and informal groups existed previously, Zuccaro envisioned a more structured institution dedicated to education, theoretical discussion, and the promotion of the arts.

Building upon earlier efforts, Zuccaro was instrumental in securing a papal charter for the Accademia in 1593 and became its first principe (president or director). He envisioned the Accademia not just as a school but as a prestigious body that would regulate artistic practice, foster talent, and provide a forum for intellectual exchange. His theoretical ideas, particularly the emphasis on disegno and the intellectual basis of art, heavily influenced the Accademia's early curriculum and philosophy.

The Accademia di San Luca aimed to teach young artists both practical skills and theoretical principles. Zuccaro believed that artists should study the works of classical antiquity and the High Renaissance masters (like Raphael and Michelangelo), not merely to copy them, but to understand their principles and ultimately surpass them through divinely inspired disegno interno. The institution played a crucial role in standardizing art education in Rome and served as a model for similar academies across Europe.

Zuccaro's involvement extended beyond Rome. He also participated in discussions regarding the reform of the Accademia del Disegno in Florence, founded earlier by Giorgio Vasari. He advocated for clearer teaching protocols and a greater emphasis on theoretical instruction within the Florentine institution as well, demonstrating his consistent belief in the importance of structured, intellectually grounded art education.

Controversies and Artistic Rivalries

Federico Zuccaro's strong personality, firm convictions, and prominent position inevitably led to conflicts and controversies throughout his career. His early clash with his brother Taddeo hinted at a competitive spirit. His most public dispute arose from the criticism of his Florence Cathedral dome frescoes.

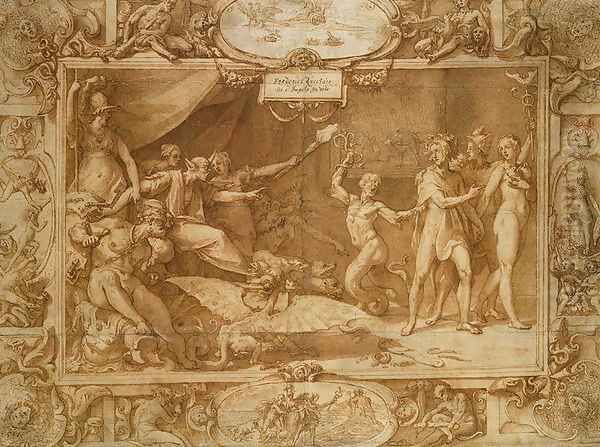

Stung by the negative reception, Zuccaro retaliated in a characteristically bold manner. He painted an allegorical work known as the Porta Virtutis (Gate of Virtue), which included satirical depictions of his critics, possibly including figures associated with the cathedral authorities. This provocative act, displayed publicly, caused a scandal. It resulted in his temporary banishment or forced departure from Rome around 1579-1580, ordered by Pope Gregory XIII. Though eventually pardoned, the incident highlights Zuccaro's sensitivity to criticism and his willingness to use his art as a weapon. Works like The Lament of Painting or allegories based on the Calumny of Apelles theme are sometimes associated with his responses to such criticisms.

Zuccaro also expressed strong opinions about his contemporaries, often reflecting a conservative defense of Mannerist principles against emerging trends. His documented criticism of Caravaggio is particularly telling. He famously dismissed Caravaggio's revolutionary naturalism, suggesting he was merely a follower of the coloristic tradition of Giorgione and lacked the foundational skill of disegno that Zuccaro prized. He reportedly quipped upon seeing Caravaggio's work in the Contarelli Chapel that he saw "nothing new" in it.

Similarly, Zuccaro criticized the Venetian painter Tintoretto. He disapproved of Tintoretto's rapid, sketchy brushwork (prestezza) and dramatic chiaroscuro, arguing that it blurred the proper distinction between a finished work (finito) and a sketch (abbozzato). He even went so far as to suggest that Tintoretto's influential style contributed to a perceived decline in the quality of Venetian painting. These criticisms position Zuccaro as a defender of academic standards and Central Italian emphasis on line and form against the more painterly and naturalistic directions gaining momentum at the turn of the century, represented by artists like Tintoretto, Veronese, and especially Caravaggio and later the Carracci (Annibale, Agostino, Ludovico).

Architecture and Legacy: The Palazzo Zuccari

Federico Zuccaro's talents extended to architecture, most famously demonstrated in the design of his own residence in Rome, the Palazzo Zuccari. Located near the Trinità dei Monti, the palace is renowned for its eccentric and highly original doorway and window frames on the Via Gregoriana, sculpted to resemble monstrous open mouths, seemingly inspired by the Mannerist garden sculptures of Bomarzo.

This unique architectural statement served not only as his home but also, in accordance with his will, as a hospice and studio space for young, impoverished artists associated with the Accademia di San Luca. The Plan of Palazzo Zuccari exists as a drawing showcasing his design. The building itself stands as a testament to his multifaceted creativity and his commitment to supporting the next generation of artists, while also undeniably serving as a monument to his own success and artistic persona. The Bibliotheca Hertziana (Max Planck Institute for Art History) is now housed there.

Federico Zuccaro died in Ancona in 1609 while traveling. He left behind a vast body of work, including paintings, frescoes, drawings (such as the biographical series Taddeo's Learning Years), and his influential theoretical writings. He stands as one of the last major figures of Italian Mannerism, a prolific artist who navigated the complex demands of patronage across Europe. His emphasis on disegno, his role in founding the Accademia di San Luca, and his articulate defense of the artist's intellectual status profoundly shaped the course of art education and theory. While his style was eventually eclipsed by the dynamism of the Baroque, Federico Zuccaro remains a crucial figure for understanding the artistic and intellectual currents of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. His career bridges the gap between the world of Vasari and the era of Caravaggio and Bernini, leaving an indelible mark on the history of Italian art.