Santi di Tito (1536-1603) stands as a pivotal figure in the artistic landscape of late 16th-century Florence. An accomplished painter, draughtsman, and occasional architect, his career unfolded during a transformative period, bridging the sophisticated complexities of late Mannerism with the burgeoning clarity and naturalism of the early Baroque. Born in Borgo San Sepolcro, the same Tuscan town that produced Piero della Francesca, Santi di Tito would become a leading proponent of a stylistic reform in Florence, advocating for a return to legibility, natural observation, and sincere piety in art, a movement often referred to as "Counter-Maniera" or "Anti-Mannerism."

Early Life and Formative Influences

Santi di Tito's artistic journey began in his native Sansepolcro, but like many aspiring artists of his time, he soon gravitated towards Florence, the vibrant artistic heart of Tuscany. In Florence, he is documented as having received training under influential masters. Among his teachers were Agnolo Bronzino, a quintessential Mannerist known for his elegant, polished, and often enigmatic portraits and allegories. Another significant figure in his early development was Baccio Bandinelli, a sculptor and painter who, despite his often-contentious personality, was a prominent artist in Medicean Florence.

Exposure to these masters would have immersed Santi di Tito in the prevailing artistic currents of High Mannerism. This style, which had evolved from the High Renaissance, was characterized by elongated figures, complex and often ambiguous compositions, artificial color palettes, and a focus on intellectual sophistication and artistic virtuosity. Artists like Giorgio Vasari, Jacopo Pontormo, and Rosso Fiorentino had earlier defined this intricate and stylized approach. Santi di Tito's early works likely reflected these influences, as he absorbed the technical skills and aesthetic sensibilities of his environment.

Roman Sojourn and Artistic Reorientation

A crucial period in Santi di Tito's development was his time spent in Rome, from approximately 1558 to 1564. Rome, with its rich tapestry of classical antiquities and High Renaissance masterpieces by artists like Raphael and Michelangelo, offered a profound source of inspiration and study. During his Roman years, Santi di Tito was actively involved in significant decorative projects. He collaborated with other artists, including Giovanni de' Vecchi and Niccolò Circignani (often called Il Pomarancio), on fresco decorations. Notable among these collaborative efforts were works in the Palazzo Salviati and the Casino of Pius IV in the Vatican Gardens (Belvedere).

This Roman experience was transformative. It exposed him not only to the grandeur of classical and High Renaissance art but also to the emerging currents of the Counter-Reformation. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) had profound implications for religious art, calling for clarity, directness, decorum, and the ability to inspire piety in the faithful. The elaborate artificiality of Mannerism was increasingly seen by some reformers as unsuited to these devotional aims. It is likely that Santi di Tito's exposure to these ideas, combined with his study of earlier masters who prioritized naturalism and clear narrative (such as Andrea del Sarto), began to steer his artistic compass in a new direction.

The Rise of Counter-Maniera in Florence

Upon his return to Florence around 1564, Santi di Tito emerged as a leading voice for artistic reform. He consciously moved away from the more extreme affectations of Mannerism, seeking a style that was more grounded, naturalistic, and emotionally accessible. This "Counter-Maniera" approach did not entirely reject the elegance of the preceding generation but tempered it with a renewed emphasis on verisimilitude, compositional clarity, and a more restrained, sincere emotional expression. His figures became less stylized and more individualized, their gestures more natural, and his compositions more ordered and legible.

His palette, while still sophisticated, often moved towards more naturalistic tones, and his use of light and shadow aimed to model forms convincingly and create a sense of tangible presence. This shift was not merely a stylistic preference but also an ideological one, aligning with the Counter-Reformation's desire for art that could effectively communicate religious narratives and inspire devotion without intellectual obscurity. He became a prominent member of the Accademia del Disegno in Florence, an institution founded by Giorgio Vasari, which played a significant role in shaping artistic practice and theory.

Major Paintings: Religious Narratives and Devotional Works

Santi di Tito's reputation rests primarily on his numerous altarpieces and religious paintings, which adorned many churches in Florence and Tuscany. These works exemplify his reformed style.

One of his most celebrated commissions was for the Santa Croce church in Florence. Here, he painted The Supper at Emmaus (c. 1574). In this work, Christ is depicted at the moment he is recognized by the two disciples. The composition is clear, the figures are rendered with a convincing naturalism, and the emotional tenor is one of quiet revelation rather than overt drama. The everyday setting and the relatable humanity of the figures would have resonated with contemporary viewers.

Another significant work in Santa Croce is the Resurrection of Lazarus (c. 1576). Again, Santi di Tito prioritizes narrative clarity. The figures react with a range of understandable emotions, from awe to concern, and Lazarus himself is depicted with a stark realism that underscores the miracle. The composition guides the viewer's eye effectively to the central event, avoiding the crowded and sometimes confusing arrangements of earlier Mannerist works.

His Vision of Saint Thomas Aquinas (c. 1593) for the church of San Marco in Florence is another masterpiece. It depicts the saint experiencing a mystical vision, with Christ appearing to him from the crucifix. The painting combines a sense of divine presence with a tangible depiction of the saint and his study. The careful rendering of textures, the thoughtful portrayal of Aquinas, and the balanced composition are hallmarks of Santi di Tito's mature style.

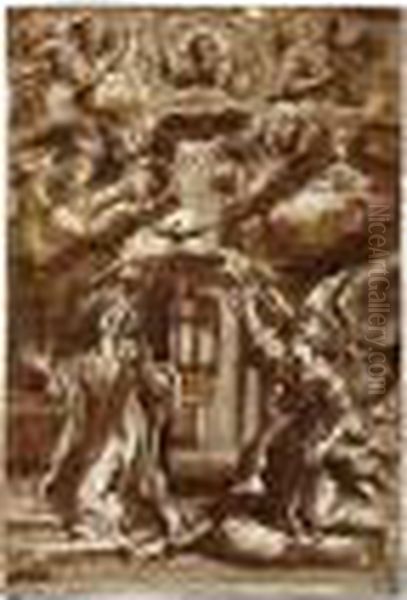

Other notable religious works include The Annunciation for Santa Maria Novella, Tobias and the Angel, and numerous depictions of the Holy Family, Madonnas, and saints. He also painted Solomon Building the Temple in Jerusalem, located in the Cappella di San Luca within the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata, which served as the chapel for the Accademia del Disegno. These works consistently demonstrate his commitment to clear storytelling, naturalistic representation, and a dignified, accessible piety.

Portraiture: Capturing Likeness and Character

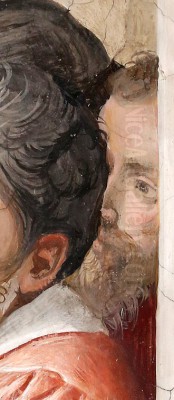

While primarily known for his religious paintings, Santi di Tito was also an accomplished portraitist. His portraits are characterized by a similar directness and naturalism found in his narrative works. He sought to capture not only the physical likeness of his sitters but also a sense of their character and social standing.

Perhaps his most famous portrait is the posthumous Portrait of Niccolò Machiavelli (Palazzo Vecchio, Florence). While the exact dating and circumstances of this portrait are debated by scholars, it has become an iconic image of the Florentine political philosopher. The portrait presents Machiavelli with a penetrating gaze and a thoughtful demeanor, conveying intellectual depth.

He also painted portraits of contemporary Florentines, contributing to the rich tradition of portraiture in the city. These works, often less formal than the state portraits of Bronzino, show a concern for capturing individual personality through subtle observation of expression and posture. His approach to portraiture, like his religious art, moved away from Mannerist idealization towards a more straightforward representation.

Architectural Endeavors

Beyond his prolific career as a painter, Santi di Tito also engaged in architecture, though his contributions in this field are less extensive and well-documented than his paintings. He is known to have designed villas, private residences, church facades, and monastic structures. One notable project was his involvement in the decorative scheme of the Studiolo of Francesco I in the Palazzo Vecchio, a quintessential Mannerist ensemble, though his role here was primarily as a painter contributing to Vasari's overall design.

He designed the Villa dei Collazzi for the Dini family, and also worked on the Villa di Spedaletto for the Corsini family. His architectural style, much like his painting, tended towards a clear, classical vocabulary, often characterized by a sense of order and proportion. However, his architectural ambitions were perhaps not as fully realized or as influential as his reforms in painting. Despite this, his engagement with architecture underscores his versatility and his deep understanding of classical principles, which informed all aspects of his artistic output.

Santi di Tito as an Educator and His Influence

Santi di Tito was not only a prolific artist but also an influential teacher. He played an active role in the Accademia del Disegno and maintained a busy workshop, training a new generation of artists. His emphasis on drawing from life, clarity of composition, and naturalism had a profound impact on his students and, through them, on the subsequent course of Florentine painting.

Among his notable pupils were Ludovico Cardi, known as Il Cigoli, who would become one of the most important figures in early Baroque Florence, further developing the naturalistic and emotionally expressive tendencies seen in Santi's work. Gregorio Pagani was another significant student who embraced a similar reformist path. Other artists associated with his studio or influenced by him include Andrea Boscolli and Luca Giorgi. The sculptor Francesco Mochi also reportedly spent time in his circle.

Through his teaching and his own example, Santi di Tito helped to steer Florentine art away from the perceived excesses of late Mannerism and towards a style that was more in tune with the religious and cultural sensibilities of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His influence can be seen in the work of many Florentine artists who followed, including Jacopo da Empoli and Bernardino Poccetti, who, while developing their own distinct styles, shared a commitment to clarity and naturalism.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu of Florence

Santi di Tito operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment. In Florence, he was a contemporary of artists like Alessandro Allori, Bronzino's pupil, who largely continued the Mannerist tradition, albeit with some evolution. Giambologna, the Flemish sculptor, dominated the sculptural scene with his dynamic and elegant Mannerist works.

The reformist impulse that Santi di Tito championed was not unique to him; similar tendencies were emerging elsewhere in Italy. In Rome, artists like Federico Barocci (though primarily active in Urbino, his influence was felt widely) were also exploring a more sensitive, emotionally resonant, and coloristically rich style. The Carracci (Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico) in Bologna were contemporaneously spearheading a major reform that emphasized drawing from life and a synthesis of High Renaissance ideals, which would be foundational for the Baroque. While Santi di Tito's reform was perhaps more localized to Florence, it shared a common spirit with these broader Italian artistic shifts.

The anecdote involving Titian, the Venetian master, who is said to have commented with a degree of irony on Santi di Tito's color, highlights the distinct regional characteristics of Italian art. Venetian painting, with its emphasis on colorito (color and painterly application), differed significantly from the Florentine emphasis on disegno (drawing and design). Santi's style remained firmly rooted in the Florentine tradition of strong draughtsmanship, even as he sought greater naturalism in color and light.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Santi di Tito remained active and respected throughout his career. He continued to receive important commissions and to play a role in the artistic life of Florence until his death on July 23, 1603. He was buried in the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata in Florence, a church for which he had undertaken significant work, including the design of the artists' chapel, the Cappella di San Luca.

In the immediate aftermath of his death, his influence persisted through his students, particularly Cigoli, who became a leading figure in the transition to the full Baroque in Florence. However, as artistic tastes evolved in the 17th and 18th centuries, Santi di Tito's reputation, like that of many artists of his transitional generation, somewhat faded. The more dramatic and dynamic qualities of High Baroque art, as practiced by artists like Pietro da Cortona or Luca Giordano, came to overshadow the more restrained and sober classicism of Counter-Maniera painters.

It was not until the 19th and 20th centuries, with a renewed scholarly interest in the complexities of Mannerism and the early stirrings of the Baroque, that Santi di Tito's significance was re-evaluated. Art historians came to recognize him as a crucial figure in the "Florentine Reform," an artist who thoughtfully navigated the stylistic and religious currents of his time. He is now appreciated for his role in revitalizing Florentine painting by infusing it with a new sense of naturalism, clarity, and sincere religious feeling, thereby paving the way for the subsequent development of Baroque art in Tuscany. His commitment to clear narrative and direct emotional appeal ensured his works remained accessible and engaging, fulfilling the Counter-Reformation's call for art that could instruct and inspire the faithful. His legacy is that of a reformer, a skilled craftsman, and an influential teacher whose art provided a vital bridge between two major epochs in Italian art history.