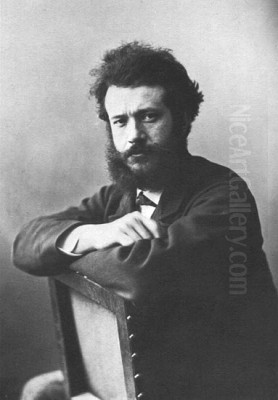

Félix Bracquemond (1833-1914) stands as a towering yet often underappreciated figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. A master etcher, influential ceramicist, painter, and an early champion of Japanese art, Bracquemond's multifaceted career connected him with many of the leading artistic movements and personalities of his time. His work not only revived the art of etching in France but also played a crucial role in the dissemination of Japonisme, profoundly impacting the Impressionists and beyond. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist whose innovations resonated across multiple disciplines.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born Joseph Auguste Bracquemond in Paris on May 22, 1833, his early life was marked by modest beginnings. He did not come from an artistic dynasty, a common path for many artists of the era. Instead, his journey into the art world began with a practical apprenticeship in a commercial lithography workshop. This initial training, while focused on reproductive techniques, provided him with a foundational understanding of printmaking processes and the importance of line and tone.

However, lithography did not fully capture his artistic imagination. Bracquemond soon found himself drawn to the more expressive and nuanced possibilities of etching. Around the age of nineteen, he began to experiment with this medium, largely self-taught in its intricacies. His natural talent quickly became apparent. He studied the works of Old Masters of etching, such as Rembrandt van Rijn and Albrecht Dürer, absorbing their technical prowess and diverse approaches to subject matter.

His formal art education included a period studying under Joseph Guichard, a former pupil of the great Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix and the Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. This eclectic tutelage exposed Bracquemond to contrasting artistic philosophies – the expressive color and dynamism of Romanticism versus the precise linearity and idealized forms of Neoclassicism. This duality would, in some ways, inform his own artistic path, which often balanced meticulous observation with innovative expression.

The Etching Revival and Bracquemond's Ascendancy

By the mid-19th century, the art of original etching had largely fallen out of favor, overshadowed by painting and often relegated to reproductive purposes. Bracquemond, alongside a few other dedicated artists like Charles Meryon and Charles-François Daubigny, became a central figure in what is now known as the French Etching Revival. This movement sought to re-establish etching as a legitimate and expressive fine art medium in its own right.

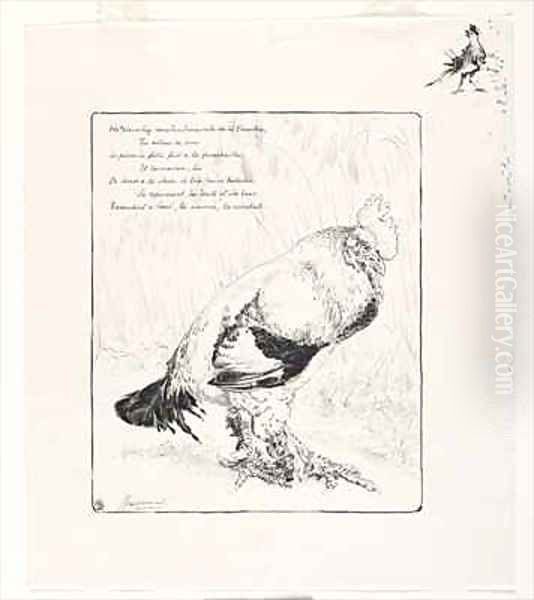

Bracquemond's technical mastery was exceptional. He explored the full range of etching techniques, including drypoint, aquatint, and soft-ground etching, often combining them to achieve rich tonal variations and textural effects. His early etchings, such as portraits and animal studies, demonstrated a keen eye for detail and a profound understanding of form. One of his most celebrated early original etchings, Le Haut d'un battant de porte (The Top of a Door Panel, 1852), showcased his ability to transform a mundane subject—a collection of dead birds and a bat nailed to a door—into a compelling and minutely observed still life. This work, exhibited at the Salon, garnered critical attention and signaled the arrival of a significant new talent in printmaking.

In 1862, Bracquemond played a pivotal role in the founding of the Société des Aquafortistes (Society of Etchers). This organization, spearheaded by the publisher Alfred Cadart, was instrumental in promoting original etching. It published albums of prints by contemporary artists, making their work accessible to a wider audience and fostering a renewed appreciation for the medium. Bracquemond was not only a contributor but also a technical advisor and a passionate advocate for the society's mission. His involvement helped to galvanize a community of artists interested in exploring the unique possibilities of etching.

Japonisme: A Revolutionary Encounter

Perhaps one of Bracquemond's most significant contributions to the course of Western art was his early and enthusiastic embrace of Japanese art, a phenomenon that came to be known as Japonisme. The story of his "discovery" is legendary in art historical accounts. Around 1856, Bracquemond reportedly stumbled upon a small volume of woodblock prints by the Japanese master Katsushika Hokusai, specifically pages from the Hokusai Manga, which had been used as packing material for a shipment of porcelain in the shop of the printer Auguste Delâtre.

Bracquemond was immediately captivated by the unfamiliar aesthetic principles he encountered: the bold, asymmetrical compositions, the flattened perspectives, the dynamic use of line, the focus on everyday subjects, and the intimate observation of nature—birds, insects, flowers, and landscapes. He began to avidly collect Japanese prints, sharing his enthusiasm with his circle of artist friends, including Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and James McNeill Whistler.

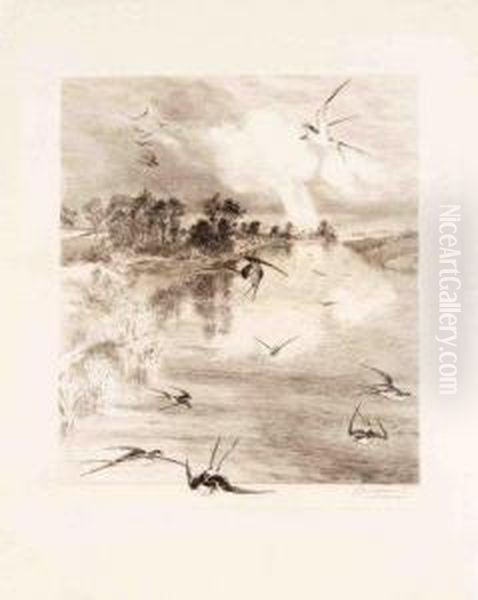

This encounter with Japanese art was transformative for Bracquemond. He began to incorporate its stylistic elements and thematic concerns into his own work, particularly in his etchings and, later, his ceramic designs. His prints featuring birds, such as Canards et Sarcelles (Ducks and Teals) or the series Les Hirondelles (Swallows), demonstrate a new dynamism and decorative sensibility clearly inspired by Japanese models. He adopted unusual viewpoints and cropping techniques, creating compositions that felt fresh and modern to his contemporaries. His influence was crucial in popularizing these Japanese aesthetic ideas among the avant-garde artists of Paris.

Innovations in Ceramic Art

Bracquemond's engagement with Japonisme found a particularly fertile ground in the field of decorative arts, specifically ceramics. In the 1860s and 1870s, he became deeply involved in ceramic design, working for prominent manufacturers such as the Haviland & Co. factory in Limoges and collaborating with Théodore Deck. He sought to elevate the status of decorative arts, arguing that they deserved the same level of artistic consideration as painting and sculpture.

His most famous ceramic design is the Service Rousseau, created around 1866 for Haviland. This dinner service was revolutionary for its time. Instead of traditional symmetrical patterns, Bracquemond adorned each piece with unique, naturalistic depictions of birds, fish, insects, and flora, directly inspired by Hokusai and other Japanese artists. The compositions were often asymmetrical, with motifs placed off-center or spilling over the edges, mimicking the spontaneity and decorative freedom of Japanese prints. The Service Rousseau was a commercial and critical success, widely exhibited and influential in popularizing Japanese-inspired design in European decorative arts.

He followed this with other notable ceramic designs, including the Service Parisien, which often featured more refined and elegant interpretations of natural motifs, sometimes combined with scenes of Parisian life. Bracquemond's approach to ceramic decoration was innovative not only in its Japoniste elements but also in his insistence on the artist's direct involvement in the design process, bridging the gap between fine art and industrial production. His work helped to usher in a new era for French ceramics, one characterized by greater artistic ambition and stylistic diversity. Other artists who contributed to the renewal of ceramics, often influenced by similar Japoniste trends or by Bracquemond himself, included Camille Moreau-Nélaton and Albert Dammouse.

Bracquemond and the Impressionist Circle

Félix Bracquemond was a key figure within the Impressionist circle, though his primary medium was etching rather than painting. He shared many of their artistic concerns: an interest in capturing fleeting moments, a focus on contemporary life and landscape, and a desire to break free from the rigid conventions of the academic Salon. He was a close friend to many of the leading Impressionists, including Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, and Claude Monet.

Bracquemond actively participated in several of the Impressionist exhibitions. He exhibited his etchings in the first groundbreaking Impressionist exhibition of 1874, held in the studio of the photographer Nadar. He also participated in the exhibitions of 1879 and 1880. His presence helped to legitimize printmaking as an integral part of the modern art movement.

His technical expertise in etching was invaluable to his Impressionist colleagues. He taught etching techniques to Manet, Degas, and Pissarro, encouraging them to explore the medium as a means of original expression. Manet, for instance, produced a significant body of etchings, often with Bracquemond's guidance. Degas, known for his experimental approach to art, also created highly innovative prints, and his discussions with Bracquemond on technique and artistic vision were undoubtedly fruitful. Pissarro, too, became a dedicated printmaker, using etching to capture the rustic charm of the French countryside.

While Bracquemond's own paintings are less known than his prints, they often show an affinity with Impressionist concerns, particularly in their depiction of light and atmosphere. His style, however, always retained a strong emphasis on drawing and structure, perhaps reflecting his grounding in printmaking and his early classical training. He was a bridge figure, connecting the traditions of printmaking with the revolutionary aims of the Impressionists. Other artists associated with the Impressionists who also explored printmaking include Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, who, like Bracquemond's wife Marie, brought unique perspectives to the movement.

Marie Bracquemond: A Shared Artistic Life

In 1869, Félix Bracquemond married Marie Quivoron, who became known as Marie Bracquemond (1840-1916). Marie was a talented painter in her own right, and her artistic journey is intertwined with Félix's, though often marked by the societal constraints faced by female artists of the era. Initially, Félix encouraged her artistic pursuits, and she studied with him. He introduced her to his circle of Impressionist friends, and she, too, began to adopt Impressionist techniques, particularly a brighter palette and a focus on capturing light and color en plein air.

Marie Bracquemond exhibited with the Impressionists in 1879, 1880, and 1886, and her work was praised by critics like Gustave Geffroy. Her paintings, such as Sur la terrasse à Sèvres (On the Terrace at Sèvres, 1880), demonstrate a delicate sensibility and a masterful handling of light. However, according to their son Pierre, Félix became increasingly critical of her Impressionist style, perhaps preferring the more structured approach he himself favored. This, combined with domestic responsibilities, led Marie to gradually abandon painting, a loss for the Impressionist movement and for art history. Despite these complexities, their home in Sèvres was a hub for artists and writers, a testament to their shared engagement with the cultural life of their time.

Collaborations and Wider Artistic Connections

Bracquemond's influence and connections extended beyond the Impressionist circle. He was a respected figure in the broader Parisian art world, known for his technical knowledge, his advocacy for printmaking, and his discerning eye. He collaborated with or provided technical assistance to numerous artists.

His friendships included figures from the literary world as well. The critic Théophile Gautier was an early supporter, and Charles Baudelaire, a champion of modern art and a keen observer of printmaking, also recognized Bracquemond's talent. These literary figures played a crucial role in shaping public perception and critical discourse around new artistic movements.

Bracquemond also interacted with artists who, while not strictly Impressionists, shared an interest in modern subjects and innovative techniques. For instance, he knew Auguste Rodin, the revolutionary sculptor, whose own drawings and experiments with printmaking shared a certain expressive energy. He was also acquainted with Jean-Louis Forain, a painter and printmaker known for his satirical depictions of Parisian life, and with the etcher Félix Buhot, who was renowned for his atmospheric and technically complex prints of urban scenes.

His role as a teacher and mentor, both formally and informally, was significant. By sharing his knowledge of etching and his passion for Japanese art, he helped to shape the artistic development of many of his contemporaries. His studio and home were places of lively discussion and artistic exchange.

Theoretical Contributions and Writings

Beyond his practical artistic output, Félix Bracquemond also contributed to art theory. In 1882, he published Du Dessin et de la Couleur (On Drawing and Color), a treatise that articulated his artistic principles. In this work, he emphasized the importance of drawing as the foundation of all art, a view that aligned with his own meticulous practice as an etcher. However, he also explored the role of color and light, reflecting the influence of Impressionism and his own observations of nature.

The book discussed the science of color, theories of perception, and the importance of direct observation. It also touched upon the decorative arts, advocating for their integration with the fine arts. Du Dessin et de la Couleur provides valuable insight into Bracquemond's artistic philosophy and the intellectual currents that shaped late 19th-century art. It shows him as a thoughtful and articulate artist, capable of reflecting critically on his own practice and the broader artistic landscape. His ideas on the harmony of color and the structural importance of line resonated with many artists seeking a balance between traditional skills and modern expression.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Félix Bracquemond continued to work prolifically throughout his later years. He received official recognition for his contributions to French art, including being made an Officer of the Legion of Honour. He remained active as an etcher and continued to be involved in the decorative arts. He passed away in Sèvres on October 27, 1914, leaving behind an extensive oeuvre of over eight hundred etchings, numerous drawings, paintings, and influential ceramic designs.

Bracquemond's legacy is multifaceted. As a printmaker, he was a key catalyst in the revival of etching as a creative art form in France. His technical virtuosity and innovative subject matter set a high standard for his contemporaries and for subsequent generations of etchers. Artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who also embraced printmaking with innovative flair, benefited from the renewed status of the medium that Bracquemond helped to foster.

His role in introducing and popularizing Japonisme in France cannot be overstated. By recognizing the artistic merit of Japanese prints and incorporating their principles into his own work, he opened up new avenues of expression for Western artists. The influence of Japonisme can be seen not only in the work of Impressionists like Monet, Degas, and Cassatt, but also in Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, and in the Art Nouveau movement.

In the realm of decorative arts, Bracquemond's ceramic designs were groundbreaking, demonstrating how artistic principles could be applied to everyday objects. He helped to blur the boundaries between fine art and applied art, contributing to a broader re-evaluation of the role of design in modern life.

Conclusion: An Artist of Synthesis and Innovation

Félix Bracquemond was an artist of remarkable versatility and vision. He navigated the complex and rapidly changing art world of 19th-century Paris with skill and intelligence, making significant contributions across multiple fields. From the meticulous craft of etching to the revolutionary aesthetics of Japonisme and the innovative designs of ceramics, Bracquemond consistently pushed artistic boundaries.

He was a vital link between different artistic currents, connecting the traditions of the Old Masters with the avant-garde spirit of Impressionism. His friendships and collaborations with a wide array of artists, including Manet, Degas, Pissarro, Whistler, and Rodin, underscore his central position in the artistic life of his time. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his Impressionist colleagues, Félix Bracquemond's influence was profound and far-reaching. His work enriched the artistic vocabulary of his era and left an indelible mark on the development of modern art, ensuring his place as a pivotal figure whose contributions continue to be appreciated and studied.