Helen Hyde (1868-1919) stands as a significant figure in American art history, particularly celebrated for her pioneering work in color etching and woodblock printing. Her artistic journey, deeply intertwined with the aesthetics and techniques of Japanese art, not only produced a body of work renowned for its sensitivity and charm but also played a crucial role in the Japonisme movement that captivated the Western art world at the turn of the 20th century. Hyde's dedication to mastering Japanese methods, her focus on the intimate lives of women and children, and her success as an independent female artist in a male-dominated era make her story compelling and her artistic contributions enduring.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Lima, New York, on April 6, 1868, Helen Hyde's formative years were spent in California, a state whose burgeoning cultural landscape would shape her early artistic inclinations. The Hyde family relocated to San Francisco in 1882, following her father's death. This move proved pivotal for young Helen, who, at the tender age of twelve, had already begun her artistic training under the guidance of her maternal uncle, Howard H. D'Estey. In San Francisco, her formal art education commenced with lessons from the Danish-American artist Ferdinand Richardt, known for his landscapes and depictions of Niagara Falls.

Hyde's early exposure to art was nurtured within a supportive family environment. Her grandmother was a descendant of Benjamin West, a prominent Anglo-American painter of historical scenes. This artistic lineage, coupled with her innate talent, set her on a path of dedicated study. After completing her secondary education in San Francisco, she attended the Wellesley School for Girls in Berkeley, further honing her skills and intellectual curiosity.

The California School of Design (now the San Francisco Art Institute) provided Hyde with a more structured and professional artistic education. Founded in 1871, it was a significant center for art training on the West Coast. Here, she would have been exposed to various artistic theories and practices, laying a solid foundation for her future explorations. Even in these early stages, her determination and passion for art were evident, characteristics that would define her career.

European Sojourn: Broadening Horizons

Like many aspiring American artists of her time, Helen Hyde recognized the importance of European study to refine her technique and broaden her artistic perspective. In 1888, she embarked on a journey to Europe, a continent then considered the epicenter of artistic innovation and tradition. Her first significant stop was Berlin, where she spent two years studying under Franz Skarbina at the Berlin Academy. Skarbina, a respected German painter and illustrator, was known for his genre scenes and Impressionistic leanings, which likely influenced Hyde's developing understanding of light and composition.

Following her time in Germany, Hyde moved to Paris in 1890, the undisputed capital of the art world. Paris was a crucible of artistic movements, from the lingering influence of Academic art to the revolutionary stirrings of Post-Impressionism. She enrolled in courses taught by notable artists such as Raphaël Collin, a popular academic painter known for his idealized female figures and decorative murals. She also studied with Albert Sterner and Félix Régamey.

It was Régamey, a French painter and illustrator with a profound interest in Japanese culture, who arguably had the most significant impact on Hyde's future artistic direction. Régamey had traveled extensively in Japan and was an enthusiastic proponent of Japonisme. He introduced Hyde to the aesthetics of Japanese art, particularly the elegance and expressive power of ukiyo-e woodblock prints. This encounter sparked a fascination that would lead Hyde to dedicate a significant portion of her career to mastering and adapting Japanese printmaking techniques. Her European sojourn, therefore, not only polished her existing skills but also planted the seeds for her unique artistic path.

The Transformative Journey to Japan

The allure of Japanese art, ignited by Félix Régamey, culminated in Helen Hyde's decision to travel to Japan in 1899. Accompanied by her friend and fellow artist, Josephine Hyde (no direct relation, though some sources suggest a distant familial connection or simply a close friendship), she embarked on an adventure that would profoundly shape her artistic identity. This was a bold move for a Western woman at the turn of the century, reflecting her adventurous spirit and deep commitment to her artistic pursuits.

Upon arriving in Japan, Hyde immersed herself in the local culture and artistic traditions. She initially studied traditional Japanese ink painting under Kano Tomonobu, a master of the prestigious Kano school, which had dominated Japanese painting for centuries. This training provided her with a foundational understanding of Japanese brushwork, composition, and aesthetic principles. However, her primary interest lay in the art of woodblock printing, the medium of the ukiyo-e masters like Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Kitagawa Utamaro, whose works had already captivated Western artists like Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and Vincent van Gogh.

Hyde sought out Japanese artisans to learn the intricate processes of color woodblock printing. This was not a simple endeavor, as the traditional ukiyo-e system involved a close collaboration between the designer, the woodblock carver, and the printer. Hyde was determined to understand and participate in all aspects of the process. She learned to carve her own blocks and eventually employed skilled Japanese carvers and printers, such as Murata Shōjirō and later Matsumoto, to execute her designs under her close supervision. This hands-on approach distinguished her from many Western artists who merely adopted Japanese stylistic elements.

Mastering the Art of Color Woodblock Printing

Helen Hyde's dedication to mastering Japanese woodblock printing, known as mokuhanga, was thorough and immersive. She spent nearly fifteen years in Japan, from 1899 to 1914, with intermittent trips abroad. During this period, she not only learned the technical skills but also absorbed the cultural nuances that informed the art form. She established a studio in Tokyo and worked closely with Japanese craftsmen, developing a collaborative yet artistically directed practice.

The traditional ukiyo-e process involved the artist creating a master drawing, which was then transferred to a cherry wood block by a carver. Separate blocks were carved for each color. The printer would then apply water-based pigments to the blocks and press them onto handmade paper. Hyde initially followed this collaborative model but increasingly took on more aspects of the production herself, aligning with the burgeoning sōsaku-hanga (creative prints) movement in Japan, where artists sought greater control over the entire process, from design to carving and printing.

Hyde's approach was meticulous. She carefully selected her subjects, often sketching extensively from life. Her prints are characterized by their delicate lines, subtle color gradations, and harmonious compositions. She adapted the Japanese techniques to her own Western sensibilities, creating a unique fusion. While her subjects were predominantly Japanese, her perspective remained that of an informed and empathetic outsider, capturing the charm and grace of Japanese life without overt exoticism. Her commitment to quality was evident in her decision to produce limited editions, typically no more than 200 impressions per image, ensuring the integrity of each print.

Themes and Subjects: A Celebration of Women and Children

The most defining characteristic of Helen Hyde's oeuvre is her tender and insightful portrayal of Japanese women and children. Her works move beyond mere ethnographic documentation, capturing the universal themes of motherhood, childhood innocence, and the quiet rhythms of daily life. She depicted women in various roles: mothers caring for their infants, young girls at play, women engaged in traditional crafts or attending festivals. These portrayals are marked by a gentle intimacy and a deep respect for her subjects.

Works like A Monarch of Japan (1901), depicting a baby boy held aloft, and The Bath (1905), showing a mother bathing her child, exemplify her focus on domestic scenes. O Tsuyu San (Miss Morning Dew, 1900) captures the delicate beauty of a young Japanese woman. Her prints often feature children in traditional attire, engaged in games, or simply observing the world around them with wide-eyed wonder. Titles such as Child of the People (1901), Baby Talk (1903), and Going to the Fair, Nikko (1910) reflect this thematic concentration.

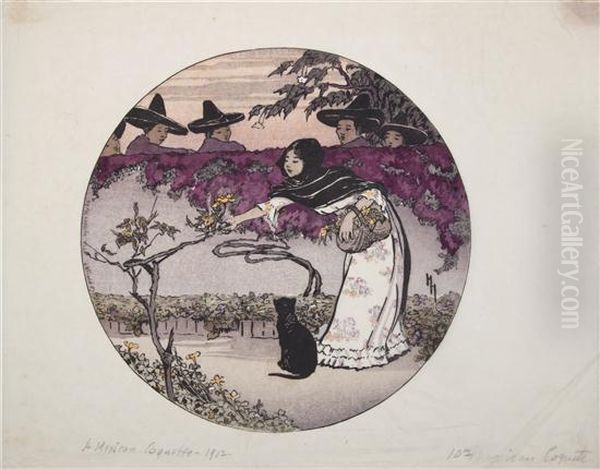

Hyde's ability to convey emotion through subtle gestures and expressions was a hallmark of her style. She often used soft, harmonious color palettes that enhanced the gentle mood of her compositions. While her primary focus was on Japanese subjects, her travels later took her to China, India, and Mexico. These experiences broadened her artistic repertoire, leading to works that depicted the people and landscapes of these regions, though her Japanese prints remain her most celebrated and influential. Her Mexican Coquette (1912) shows her applying her sensitive observational skills to a different cultural context.

Artistic Style: A Harmonious Blend of East and West

Helen Hyde's artistic style is a masterful synthesis of Eastern and Western traditions. Her deep immersion in Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e prints, provided her with a rich vocabulary of compositional devices, color sensibilities, and linear expression. From Japanese art, she adopted flattened perspectives, asymmetrical compositions, the use of negative space, and a focus on pattern and decorative detail. The strong outlines and clear forms characteristic of ukiyo-e are evident in her work.

However, Hyde did not simply replicate Japanese models. Her Western training, which included exposure to Impressionism and academic realism, informed her approach to light, form, and naturalism. While her figures are often stylized in a manner reminiscent of Japanese prints, they also possess a sense of volume and individuality that reflects her Western artistic heritage. Artists like Mary Cassatt, who also drew heavily from Japanese prints for her depictions of mothers and children, provide a point of comparison, though Hyde's direct engagement with Japanese production methods was more profound.

Her color palette was particularly distinctive. She favored soft, often muted, tones, achieving subtle gradations and harmonies that contributed to the lyrical quality of her prints. She was adept at using the Japanese technique of bokashi (color gradation) to create atmospheric effects and a sense of depth. Her etchings, though fewer in number than her woodblock prints, also demonstrate a delicate touch and a keen eye for detail, often employing color to enhance their expressive impact. This fusion of techniques and aesthetics allowed her to create a body of work that was both innovative and accessible, appealing to audiences in both the East and West.

Key Works: A Closer Look

Several of Helen Hyde's works stand out as particularly representative of her artistic achievements and thematic concerns.

_The Bath_ (1905): This color woodblock print is one of Hyde's most iconic images. It depicts a mother tenderly bathing her child in a traditional Japanese wooden tub. The composition is intimate, focusing on the gentle interaction between mother and child. The soft colors, delicate lines, and the serene expressions on the figures' faces convey a sense of warmth and domestic tranquility. The patterns of the mother's kimono and the simple setting contribute to the overall harmony of the piece.

_O Tsuyu San_ (Miss Morning Dew, 1900): An early success, this print portrays a young Japanese woman in a beautifully patterned kimono, holding a parasol. Her slightly averted gaze and delicate features capture a sense of demure grace. The title itself evokes a poetic sensibility. This work demonstrates Hyde's early mastery of the woodblock medium and her ability to convey the subtle beauty of her Japanese subjects.

_A Monarch of Japan_ (1901): This charming print features a chubby Japanese baby boy, held proudly, perhaps by a parent whose hands are just visible. The child's direct gaze and regal, if somewhat comical, demeanor, justify the playful title. The print showcases Hyde's skill in capturing the innocence and universal appeal of childhood. The use of vibrant colors in the baby's attire contrasts with a simpler background, focusing attention on the central figure.

_Going to the Fair, Nikko_ (1910): This print captures a lively scene, likely depicting a family outing to a festival or fair in Nikko, a town famous for its shrines and natural beauty. Such works allowed Hyde to explore narrative elements and depict Japanese customs and social life. The details of clothing, accessories, and the interactions between figures provide a glimpse into the everyday experiences of Japanese people.

_Mother with Infant and Small Boy_ (1901): Another tender depiction of motherhood, this print emphasizes the close bond within a family. The composition often draws the viewer into the intimate circle of the figures, highlighting the protective and nurturing aspects of maternal care. Hyde's sensitivity to these universal human experiences resonated deeply with her audience.

These works, among many others, illustrate Hyde's consistent themes, her technical proficiency, and her unique ability to bridge cultural divides through her art. Her prints were not merely decorative; they offered a window into a different world, rendered with empathy and artistic integrity.

The Business of Art and Economic Independence

Helen Hyde was not only a dedicated artist but also a savvy businesswoman who managed her career with remarkable acumen, particularly for a woman of her era. She achieved economic independence through the sale of her art, a significant accomplishment at a time when female artists often faced considerable professional and financial obstacles. She never married, dedicating her life to her artistic pursuits and maintaining her autonomy.

Hyde's prints were produced in limited editions, typically ranging from 50 to 200 impressions. This practice not only ensured the quality of each print but also created a sense of exclusivity that appealed to collectors. She priced her works accessibly, with prints selling for between $2 and $15 in the early 20th century, allowing a broader audience to acquire her art. By 1914, it is estimated that she had sold around 16,000 prints, a testament to her popularity and business sense.

She actively promoted her work through exhibitions in both the United States and internationally. She had a significant solo exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, a prestigious venue that underscored her growing reputation. Her work was also sold through dealers in major cities like San Francisco (Vickery, Atkins & Torrey) and New York (Macbeth Gallery). Her participation in major international expositions, such as the Paris Exposition of 1900 where she reportedly won a first prize (though some sources debate the specifics of this award), and later the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, where she won a gold medal for etching, further enhanced her visibility and critical acclaim.

Hyde in the Context of Japonisme

Helen Hyde's career unfolded during the peak of Japonisme, the late 19th and early 20th-century Western fascination with Japanese art and culture. This movement profoundly influenced many leading artists, including Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and James McNeill Whistler. These artists were captivated by the novel compositions, flattened perspectives, bold use of line, and decorative qualities of ukiyo-e prints.

Hyde's engagement with Japonisme was distinct and arguably more profound than that of many of her contemporaries. While artists like Van Gogh copied Japanese prints and Cassatt adapted their compositional strategies, Hyde went further by immersing herself in Japanese culture and mastering the traditional techniques of woodblock printing at their source. She lived and worked in Japan for an extended period, collaborating directly with Japanese artisans. This deep, hands-on engagement set her apart.

Her work contributed significantly to the Western understanding and appreciation of Japanese aesthetics. She acted as a cultural bridge, translating the subtleties of Japanese life and art for a Western audience. Unlike some Orientalist art that exoticized or stereotyped Eastern cultures, Hyde's portrayals were generally characterized by empathy and a genuine appreciation for her subjects. Her success helped to popularize Japanese-inspired art in America and demonstrated the rich artistic possibilities that could emerge from cross-cultural exchange. She, along with other American artists like Arthur Wesley Dow, who also promoted Japanese principles in art education, played a vital role in integrating these influences into American art.

Contemporaries, Collaborators, and Students

Helen Hyde's artistic journey was shaped by interactions with various teachers, fellow artists, and collaborators. Her early instructors, Ferdinand Richardt in San Francisco, and later Franz Skarbina, Raphaël Collin, and particularly Félix Régamey in Europe, provided her with foundational skills and, in Régamey's case, the crucial introduction to Japanese art.

In Japan, her collaboration with skilled carvers and printers was essential to the production of her woodblock prints. While the names of all these artisans are not always widely recorded, individuals like Murata Shōjirō and Matsumoto were instrumental in translating her designs into finished prints. This collaborative aspect was typical of traditional ukiyo-e production and Hyde adapted it to her own artistic vision.

She was also part of a community of Western artists working in Japan or influenced by Japanese art. Josephine Hyde, her travel companion, also pursued printmaking. Bertha Lum, another American woman artist, arrived in Japan shortly after Hyde and also became known for her color woodblock prints, sometimes studying with the same artisans. Lilian May Miller was another notable American woman who created woodblock prints in Japan, continuing the tradition. Hyde was also a member of the San Francisco Sketch Club, an organization for women artists, indicating her connections within the American art scene.

Hyde's influence extended to teaching. While not primarily known as an educator in a formal institutional sense, her work and methods inspired others. The success of artists like Bertha Lum and Margaret Kermode, who also worked in similar veins, can be seen as part of the broader interest in Japanese printmaking that Hyde helped to foster. Her dedication to the medium and her successful career served as an example for other artists, particularly women, seeking to explore non-traditional artistic paths.

Challenges and Triumphs

Helen Hyde's career was marked by significant triumphs, but she also navigated the challenges faced by artists, especially women, in her era. The art world at the turn of the 20th century was largely male-dominated, and women often struggled for recognition and professional opportunities. Hyde's ability to establish a successful international career and achieve financial independence as an unmarried woman was a remarkable feat.

Printmaking itself, particularly color woodblock printing, was not always accorded the same status as "high art" forms like oil painting or sculpture in the West. Part of Hyde's achievement was in elevating the perception of this medium through the quality and artistic merit of her work. She demonstrated that printmaking could be a powerful and expressive art form in its own right.

Living and working in a foreign culture like Japan presented its own set of challenges, from language barriers to cultural differences. Hyde's perseverance and adaptability were crucial to her success. She managed to build relationships with Japanese artisans and navigate the complexities of producing her art in this collaborative environment.

Her international acclaim, evidenced by awards at expositions and the acquisition of her work by major museums like the Art Institute of Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum, the Library of Congress, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, speaks to the widespread recognition of her talent. Her ability to create art that resonated with both Western and, to some extent, Japanese audiences (though her primary market was Western) was a significant triumph.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Helen Hyde returned to the United States around 1914, as World War I began to unfold, making international travel and residence more difficult. She initially settled in Chicago, where her brother lived, and later moved to Pasadena, California. She continued to create art, including etchings and paintings, and exhibit her work. Her subjects expanded to include American scenes and portraits, as well as depictions from her travels in Mexico.

Tragically, Helen Hyde's prolific career was cut short. She passed away from cancer on May 13, 1919, in Pasadena, California, at the relatively young age of 51. Despite her premature death, she left behind a significant body of work, comprising over 67 color woodblock prints, numerous etchings, and paintings.

Her legacy is multifaceted. Artistically, she is remembered as a pioneer of color woodblock printing in the West, one of the foremost American practitioners of Japonisme. Her sensitive and empathetic portrayals of Japanese women and children remain her most beloved and enduring contribution. She successfully fused Eastern techniques with Western sensibilities, creating a unique and appealing artistic voice.

As a female artist, Hyde was a trailblazer. Her independence, professionalism, and international success provided an inspiring model for other women artists. She demonstrated that it was possible to achieve critical and commercial success outside the conventional paths often prescribed for women.

Her work continues to be collected and exhibited, and her prints are prized for their delicate beauty and technical skill. Museums around the world hold her art in their collections, ensuring its accessibility to future generations. Helen Hyde's art serves as a lasting testament to the power of cross-cultural artistic exchange and the enduring appeal of images that capture the quiet grace of human experience. Her contribution to the Japonisme movement and to American printmaking ensures her place as an important figure in the history of art.

Conclusion

Helen Hyde's artistic journey from California to the studios of Europe and the vibrant cultural landscape of Meiji Japan is a story of passion, dedication, and remarkable artistic synthesis. As a pioneering American printmaker, she not only mastered the intricate techniques of Japanese color woodblock printing but also infused them with her unique Western perspective, creating a body of work celebrated for its tenderness, beauty, and profound humanism. Her focus on the intimate lives of Japanese women and children offered a window into a distant culture, rendered with empathy and artistic integrity, contributing significantly to the Japonisme movement.

Beyond her technical skill and aesthetic innovations, Hyde's life as an independent, economically self-sufficient female artist in the early 20th century was an achievement in itself. She navigated the complexities of the art world and cross-cultural collaboration with grace and determination, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire. Her art, housed in prestigious collections worldwide, remains a testament to her unique vision and her role as a vital cultural bridge between East and West, securing her an honored place in the annals of American and international art history.